How the Thirty Years’ War Weakened Spain

Reading time: 5 minutes

The Thirty Years War (1618-1648) wasn’t a conflict as much as a vortex that sucked every major European power into it only to spit them out battered and bruised a few years later. We have talked about how it started in Prague and how Sweden got involved; in this article, it’s Spain’s turn.

By Fergus O’Sullivan

For a war that was sparked in what’s now Czechia and was fought mainly in Germany, you may find it odd that Spain would be involved. After all, it’s practically on the other side of the European continent. However, Spain had a lot more territory then than it does now, and strong family ties with the Austrian royal house.

At the time the war started, in 1618, both Spain and Austria were ruled by branches of the house of Habsburg. In fact, until just a few decades before the two countries were united in a massive empire that spanned not just Spain and Austria, but parts of what’s now Czechia, Germany, the Netherlands, France and Italy.

However, the empire had been split: one branch of the Habsburg family got the Central European possessions, while the other got Spain, the Americas and, critically, the Netherlands. At the time, the Netherlands was one of the richest parts of the world and their possession meant a huge amount of money flowing into Spanish coffers.

The Spanish Road

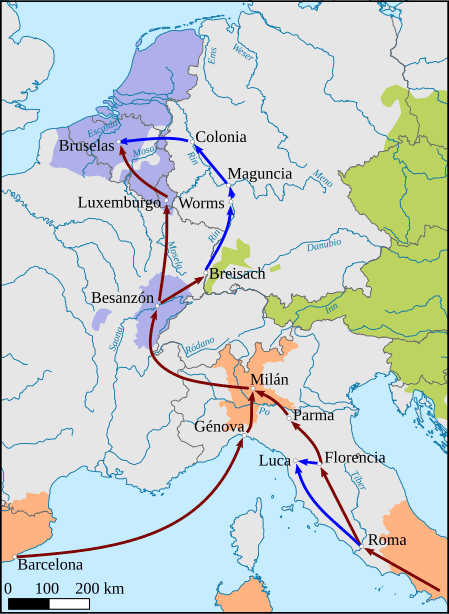

However, the Netherlands and Spain are far apart, something which became crucial when revolt broke out in those provinces during the late 16th century. The Dutch fleet was strong, so transporting troops by sea wasn’t safe. Instead, Spain used what would be called the Spanish Road, a chain of possessions either owned or controlled by Spain that stretched from the Spanish mainland to the Netherlands.

Though this route wasn’t entirely overland, the short boat trip from Spain to Italy wasn’t in any danger of Dutch marauders. Spain ended up sending hundreds of thousands of troops during the eighty years it fought to keep the Netherlands in the Habsburg fold, so there’s no way to overestimate its importance.

As you can see on the map, though, much of the Spanish Road comes close to Germany or is even part of it. The intricate system of alliances brokered by the Habsburg houses kept this route safe until war broke out in Germany between the Protestant states there and the so-called Catholic League, headed by Austria, in a conflict now known as the Thirty Years War.

Not only did this endanger the Spanish Road, it also mirrored Spain’s own struggle in the Netherlands, with scrappy heretics fighting the mother church and the kings that supported it. In fact, there were real fears that the German protestant princes would team up with the Dutch rebels. Plenty of reasons for Spain and Austria to work together against these threats, even without the bonds of blood between the royal houses.

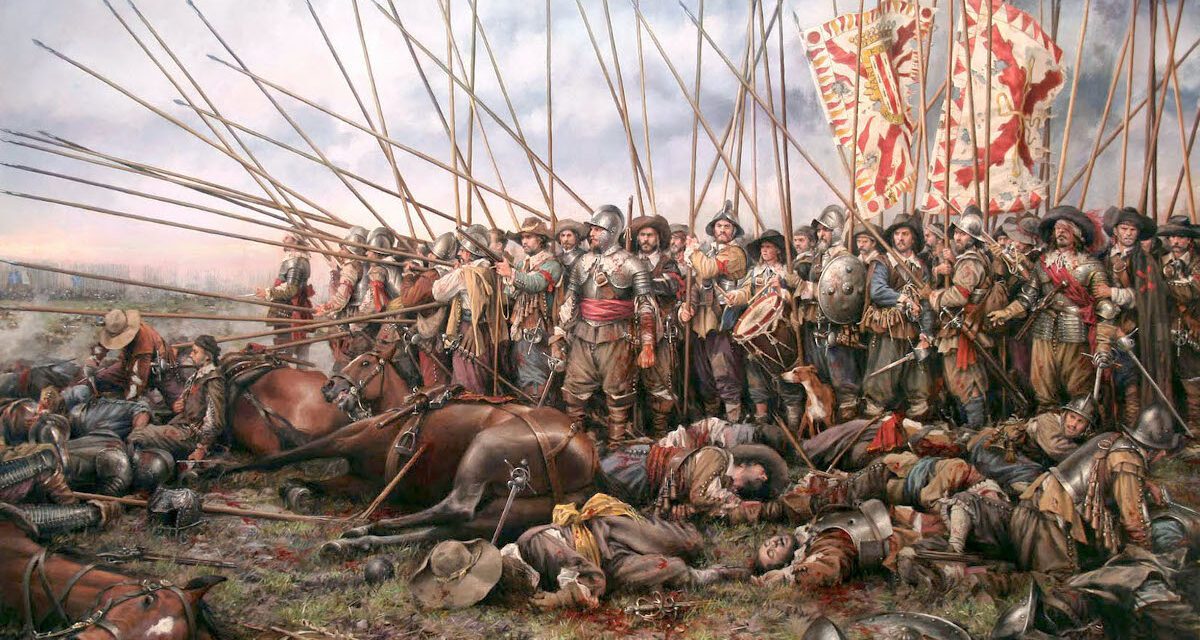

Spain duly sent troops to help their Austrian brethren. It peeled off parts of the Army of Flanders (the army fighting the Dutch) as well as sending fresh troops from Spain, and they helped to keep the Protestant German princes in line. It’s doubtful that the Austrian emperor would have done as well as he did without the help of his Spanish cousin. Well, at least until Sweden joined the Thirty Years War.

Imperial Overstretch

Thing is, fighting one war on the other side of the continent is no small proposition, let alone two. The first few years of the Thirty Years War Spain could still handle the pressure because there was no fighting in the Netherlands thanks to the Twelve Year Truce. When that ended in 1621, though, Spain was fighting on two fronts in northern Europe.

This was problematic, because either fight was worthy of Spain’s full attention and required all the manpower Philip III and IV, the Spanish monarchs at the time, could bring to bear. Even fully concentrating on either Germany or the Netherlands would have been tricky, too, since Spain had plenty of other causes to worry about, from rebellions in Catalonia, to keeping order in the recently annexed Portugal and, of course, conquering the New World.

Even if Spain could muster more troops, it was the Spanish Road, not the Spanish Highway. Getting troops to the Netherlands or Germany still took months. Even there, it wasn’t like they could quickly shuffle armies around. While the Spanish armies booked some amazing successes at first, even small defeats sapped them of strength they couldn’t spare.

Financial Woes

The problems weren’t just military, either: running a global empire and all the troops it needs is quite simply a very, very expensive proposition. The Spanish war machine pretty much ran entirely on silver from the New World, which isn’t the greatest way to run an economy as it would eventually cause massive runaway inflation.

On top of that, the silver needed to be moved from the New World to Spain, and while underway it was at risk of interception by the Dutch. In 1628, the entire silver fleet was captured by a Dutch admiral named Piet Hein, a major part of the forming of the Dutch colonial empire. Here’s an interesting video about it.

This annual fleet was the cork on which the Spanish army floated, without it Spain was in real trouble. For some reason, some of the more hawkish elements at the Spanish court decided that now was the best possible time to pick a fight with France over some territorial issues in Italy.

At this point, Paris was already considering intervention in Germany and with Spain now pestering it, too, France decided to stride on stage. This started what’s now called the French stage of the Thirty Years War, and heralded the swan song of Spain. With wars on all fronts and an economy that wasn’t getting its silver fix, Spain’s heyday, at least in Europe, was over.

Articles you may also like

Left to ruin: we must preserve our forgotten wartime defences

Reading time: 5 minutes

Australia built a number of coastal defences to help protect the country from any enemy attack during the second world war. Now, almost 80 years later, some of the physical remnants of those historic facilities lie forgotten and decaying.

These monuments to the nation’s home defence are in desperate need of preservation. While their condition varies greatly, too many have faded into obscurity.

David Grann’s The Wager: a drama of murder, insurrection, escape and an empire at sea

Reading time: 7 minutes

In 1740, a modest squadron of ships from Britain’s Royal Navy departed Portsmouth in pursuit of an immoderate treasure. Commodore George Anson, who led the flotilla, was tasked with sailing south and west across the Atlantic Ocean, rounding Cape Horn, and interfering in imperial Spain’s lucrative trans-Pacific trade. But even before the mission got underway, its prospects of success appeared dubious. A sizeable proportion of the roughly 2,000 sailors and non-seamen under Anson’s command lacked suitable experience. Worse still was the fact that so many of them took up their posts already in a parlous state of health. It is little surprise, therefore, that Anson’s “famous” voyage around the world proved to be, for most of the men who undertook it, a journey of no return.

Remembering the Victory at Bardia

Just over 80 years ago, Australian forces fought their first major battle of World War II. Bardia, a small town on the coast of Libya, some 30 km from the Egyptian border, was an Italian stronghold. The Australian troops occupied Bardia, defeating the Italians in a little over 3 days. Australian veteran, Phillip Wortham, simply […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.