Reading time: 5 minutes

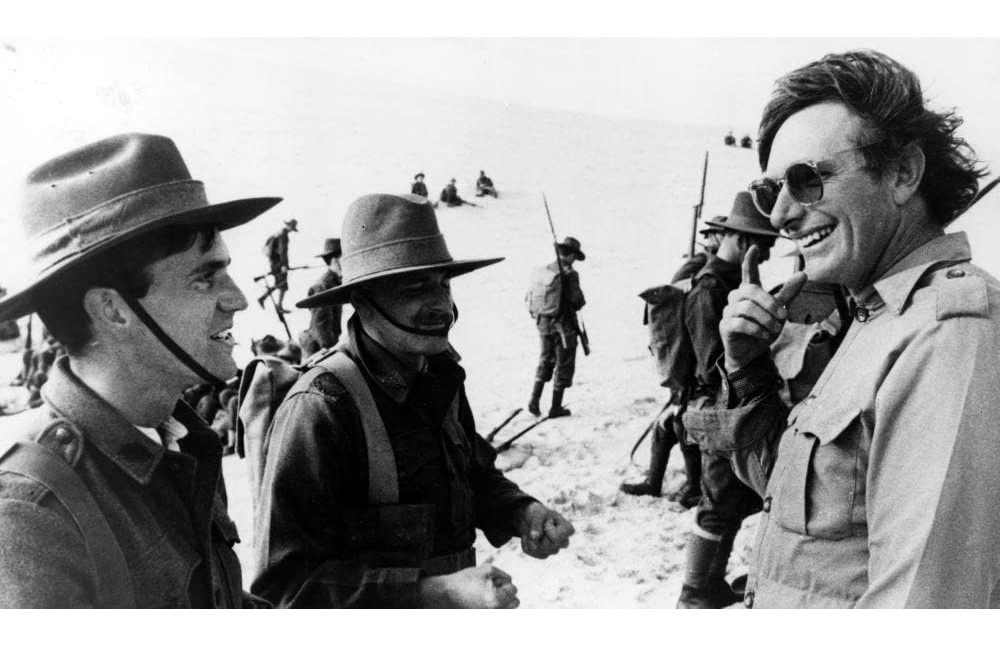

Australia built a number of coastal defences to help protect the country from any enemy attack during the second world war. Now, almost 80 years later, some of the physical remnants of those historic facilities lie forgotten and decaying.

These monuments to the nation’s home defence are in desperate need of preservation. While their condition varies greatly, too many have faded into obscurity.

By Alexander Mitchell Lee, Australian National University

Read more: What happens now we’ve found the site of the lost Australian freighter SS Iron Crown, sunk in WWII

In defence of Wollongong

For example, if you take a drive through the city of Wollongong today you could be forgiven for thinking the city played no role in the war. There is little indication this city was once heavily defended against a much-feared Axis attack.

If you take a 15-minute drive south of the city centre you’ll find some remnants of the city’s home defences. The well-developed Port Kembla Heritage Park, with its cluster of tank traps and ruined gun instalments, alludes to the history of a city that was once extremely important to Australia’s war effort.

This site, known as Breakwater Battery, was the first, smallest and weakest of three interconnected strongpoints designed to defend the industry of the Illawarra region of New South Wales from attack.

But this raises the question: where are the other two stronger points of Wollongong’s defensive network?

Our hidden defences

These sites still exist but are hidden. If you head to the leafy suburb of Mount Saint Thomas or Hill 60 Park in Port Kembla, you will find the more impressive remnants of the city’s defences.

Mount Saint Thomas and Hill 60 Park once hosted the military centres of Fort Drummond and the Illowra Battery respectively.

Dug into the hillside in both locations are impressive concrete casemates that once housed powerful naval guns. Hundreds of men and huge amounts of Australia’s limited wartime resources were dedicated to building and staffing these sites in the wartime period from 1941-1942.

The Illowra Battery, sitting right on the coast, was designed to replace Breakwater Battery as the pivot of local defences. It was strengthened over time with barbed wire, radar and tunnels deep in the hillside.

In the case of Fort Drummond, the 9.2-inch coastal guns were originally slated to be installed in Darwin in the Northern Territory, but were diverted south to strengthen the defences of Wollongong.

The prioritisation of the defence of Wollongong over Darwin, which was bombed, shows just how important protecting this southern region was.

The three strong points were designed to operate in concert to defend the region from an attack on Australia’s manufacturing core.

The industrial Illawarra was an economic behemoth for wartime Australia, producing everything from bullets to aircraft parts. It exported the materials of war across the British Empire, as far away as England and Singapore, and alongside Newcastle (in NSW) was the heart of Australian industry.

Yet, despite their important role in the war, these monuments are now overgrown, slowly being reclaimed by nature.

Read more: Lest we forget our other heroes of war, fighting for freedom at home

Kept in the dark

In the 1960s and early 1970s, the dark tunnels of Fort Drummond were converted to mushroom farms, not military history attractions.

As for Hill 60, instead of being developed as a tourist attraction the place has appeared on lists of the most haunted places in the Illawarra.

Reports five years ago that Hill 60 would be redeveloped, opening the tunnels, adding signage and highlighting the area’s Aboriginal history, have come to nothing.

Such stories of neglect are repeated at other defence sites across Australia.

Significant sites in Sydney, Brisbane, Adelaide and Newcastle are dilapidated and eroding.

Even in areas of historical significance to Australia, where the country’s colonial history has been well preserved, such as the Sydney suburb of La Perouse, the nearby second world war artillery battery sites and lookout posts are neglected.

Considering these sites are often in idyllic locations and — by necessity at the time they were built — boast impressive ocean views, it is odd their value, even as tourist sites, remains unrealised.

There are other sites across Australia that have received investment in preservation, such as Fort Lytton in Brisbane and Fort Scratchley in Newcastle. These are now tourist destinations.

Read more: The Cowra breakout: remembering and reflecting on Australia’s biggest prison escape 75 years on

With relatively small investments the neglected sites could be made more accessible. The public would then be able to learn and understand their history and significance.

Signposting, basic repairs and publicising these important relics of our wartime history would be easy first steps to revive public interest in these locations.

The educational and touristic values of Australia’s second world war defences are readily apparent. All they require is a little bit of attention after so many decades of neglect.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Articles you may also like

Scans reveal new details of how Egyptian pharaoh met a violent death

Reading time: 4 minutes

For Seqenenre Taa II, the violent injuries were possibly the result of dying in battle or execution by a king who had invaded the north of the country. One theory also suggested he was killed while sleeping. In the new study, the team applied computed tomography (CT) scanning to the remains to investigate further. CT is a non-invasive imaging method that basically layers multiple X-rays on top of each other in order to create three dimensional images of both the soft and hard tissues. We usually think of it in clinical settings, but it has a long history of use in forensic contexts to safely study remains contained inside wrappings or body bags.

The Anglo-Zanzibar War: The Shortest War in History

The story of the shortest war in history begins with a treaty between colonial powers. In 1890, Britain and Germany signed the Heligoland-Zanzibar treaty which secured spheres of influence in East Africa. Germany was given control of mainland Tanzania, while Zanzibar fell under British control.

We have revealed a unique time capsule of Australia’s first coastal people from 50,000 years ago

Reading time: 5 minutes

Barrow Island, located 60 kilometres off the Pilbara in Western Australia, was once a hill overlooking an expansive coast. This was the northwestern shelf of the Australian continent, now permanently submerged by the ocean.

Our new research, published in Quaternary Science Reviews, shows that Aboriginal people repeatedly lived on portions of this coastal plateau. We have worked closely with coastal Thalanyji Traditional Owners on this island work and also on their sites from the mainland.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.