Reading time: 8 minutes

The Dutch colonial empire was a large collection of territories that spanned the globe from the Americas to Asia. It held together for about 400 hundred years and made its mother country a fortune, wealth that persists today. What was the reason that the Netherlands, a tiny country with very few natural resources, was able to become a major player on the world stage? In this article we’ll take a look at how picking a fight with the biggest boy in the yard helped the Dutch found an empire.

By Fergus O’Sullivan

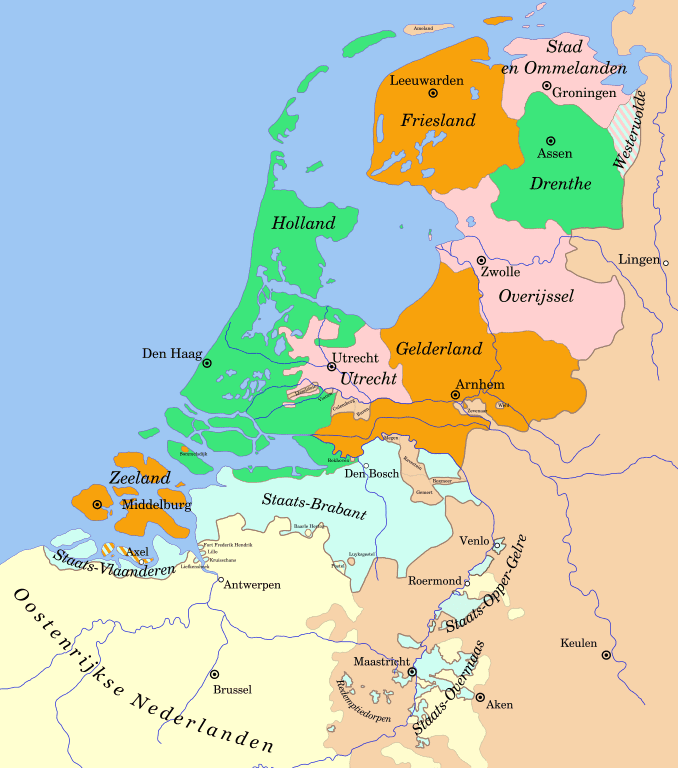

When discussing the Dutch colonial empire it’s easy to think that it came out of nowhere, that the Dutch Republic was lifted from the fens overnight and sculpted into a world power over a few decades. However, even during the Middle Ages the Dutch Low Countries, an area which comprises both the westernmost part of the modern Netherlands as well as the west of what is now Belgium, was one of the richest regions in Europe, rivaled only by the Italian city states.

This was due to a few reasons, foremost of which was trade: in a time when most trade was conducted over water (horse-drawn carts are slow, don’t carry all that much and are expensive to run), it paid to be near a coast. Since the Low Countries had a long coastline, as well as numerous river deltas and lakes, goods could be moved through the region quickly and at low cost.

Thanks to this flow of trade, many cities in the Low Countries had become centers of industry, too. Cities like Bruges and Antwerp in Flanders were famed for their wealth, and cities further up north in the province of Holland were starting to develop, too. As such, over the course of the Late Middle Ages and the early premodern period, having control over these regions meant full coffers.

Spanish Overlordship and Revolt

By the late 16th century, suzerainty over the Low Countries lay with the king of Spain thanks to a convoluted history of Burgundian-Habsburg intermarriage, backstabbing and general chicanery; the details are many and, as many a Dutch high school student will attest, tediously boring.

Philip II of Spain, however, proved to be the wrong overlord for the Netherlands and the provinces rose in revolt in 1568. You could easily fill a library with books about how the Dutch Revolt came about, but in short it was a combination of excessive taxation of the cities by the Spanish crown, as well as a brutal repression of the growing Protestant minority in the Low Countries.

The Revolt wasn’t an unmitigated success: in the end it took 80 years before the Netherlands made peace with Spain, and then only the northern provinces were independent; the south (now much of Belgium) would remain in Habsburg hands. As such, the Revolt is often called The Eighty Years’ War in Dutch sources. Below a recap of the main events.

Power by Sea

16th century Spain was one of the most powerful countries in the world at the time. Its fleets reigned supreme over much of the world’s seas and its armies strode across Europe like they owned the place. Well, in fairness, they kind of did, at its height the Habsburg monarchy had control over huge swathes of the continent.

There was no way for the Dutch to consistently beat the Spanish armies and, despite some amazing from-the-jaws-of-defeat victories, for a large part of the war the rebels struggled against the land forces sent against them. The Spanish also quickly gained a reputation for being brutal victors, due to the horrors visited upon the people of Antwerp after their city fell, as well as the aftermath of the Siege of Haarlem.

Spanish sea power was equally impressive, at least until Philip II got the idea to invade England. After the Spanish armada met its untimely end in 1588, it was a different story. The loss of the armada and with it much of Spain’s naval power was a gap gleefully exploited by a number of powers, not the least among which were the Dutch.

Already a proud seafaring people, they ramped up shipbuilding and started terrorising the Spanish wherever they could. At first, they raided Spanish-held towns along the Dutch coast, but quickly they set their sights on far richer prizes.

Privateering for Fun and Profit

Much of the Netherlands’ nascent sea power was turned to disrupting Spanish traffic from the Americas to Europe. Any Spanish ship was a target, but Dutch privateers especially preyed upon the treasure fleet, an annual convoy that transported the silver from Spanish Peru back to the motherland. In 1628 a Dutch admiral named Piet Hein captured it; to this day there’s a children’s song about the event. Below a slightly bombastic rendition.

To support these predatory practices, the Dutch captured several islands in the Caribbean from which to launch raids, as well as grow their own sugar. They also served as way stations for the Dutch slave trade to Suriname, a colony in Dutch Brazil, as well as with other, non-Dutch, territories. These islands are part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands to this day.

Sailing East

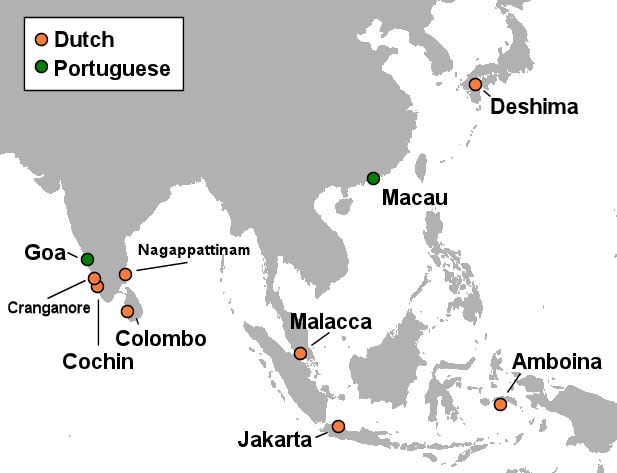

Disrupting Spanish trade wasn’t reserved to just the Western hemisphere, either: the Dutch did plenty of damage to their occupier’s economy in Asia and Africa as well. Thanks to a personal union of the crowns of Spain and Portugal under Philip II and his successors, many Portuguese possessions came under the Spanish crown and thus became targets of the Dutch.

However, the Portuguese didn’t have the same stranglehold on power in the East as the Spanish had in the West. As such, the Dutch weren’t just out to raid and plunder them, but to replace them and take hold of the insanely profitable trade in spices flowing from the Indies.

Check out our article on the wreck of the Batavia for a detailed description of one event from this era.

Over the course of the early 17th century, the Dutch picked off weaker Portuguese holdings in India, South East Asia and what’s now Indonesia. Though Portugal hung on to several of its larger possessions, like Goa and Macau, thanks to Dutch predation it saw its power in Asia greatly reduced.

Foundation of Empire

The possessions taken from Portugal ended up being the foundations for what would become the Dutch East Indies, a huge slab of territory that the Dutch held for about 400 years, though not always to the benefit of the people that lived there (read our article on the Aceh Wars for one example. Much the same goes for the Caribbean islands stolen from Spain.

The seeds of Dutch colonialism lie in the struggle for the Low Countries independence from Spain. Had Philip II and his successors maybe not held the reins so tight, there’s no telling how history could have run, instead. Maybe the Dutch shipyards would have been put to work for the Spanish crown? Perhaps without easy targets in far-off lands, the Dutch would have been content to be a regional power? Of course, we’ll never know, and Spanish repression and Dutch empire seem to go hand in hand.

Articles you may also like

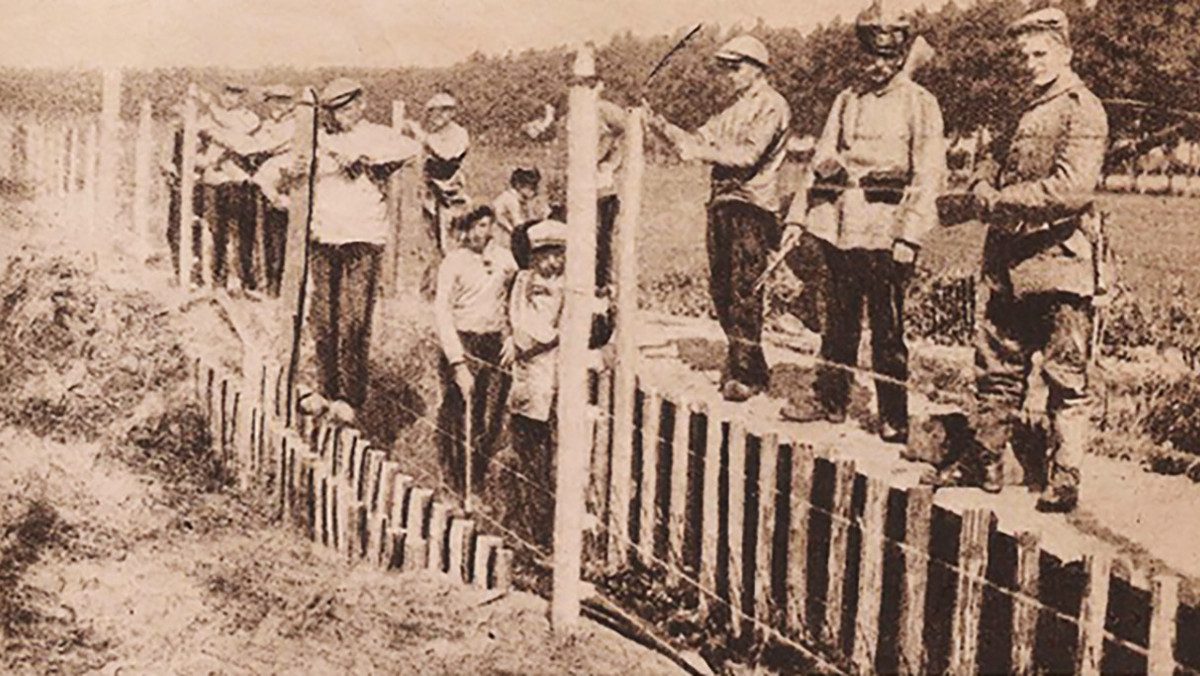

Neutrality At All Costs: The Netherlands in WW1

By Fergus O’Sullivan World War 1 was a conflict that engulfed entire continents and swallowed up whole generations of men. It is the cause of trauma that has stayed with entire nations, even now, more than a century since it ended. However, for some countries the Great War is no more than a footnote in […]