Reading time: 4 minutes

As a Roman historian, I’m struck by how often people ask why the Roman empire ended, since a far more interesting question is surely how it managed to survive for such a long time while extended over such an enormous area.

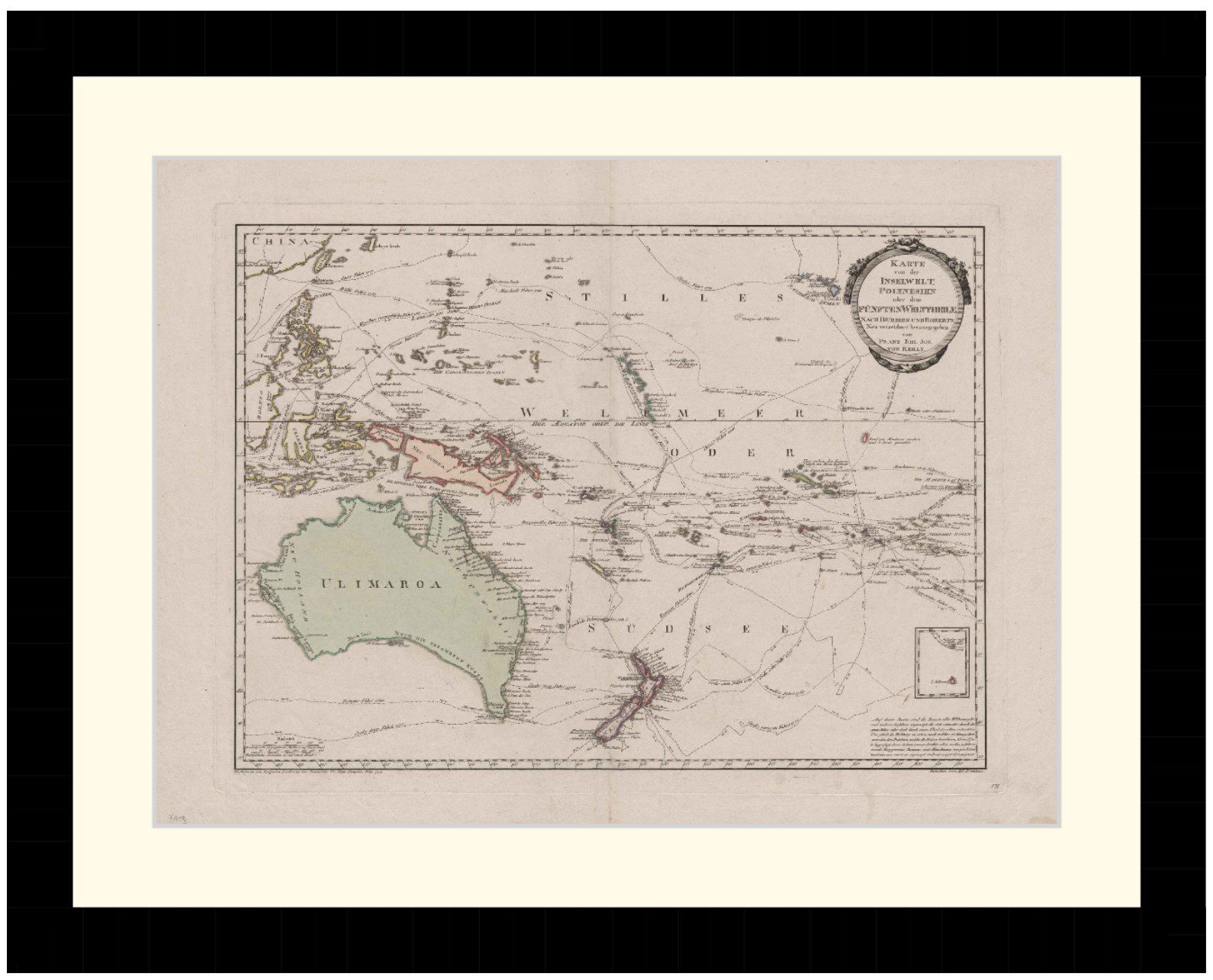

At its largest, the Roman empire encompassed an area from Spain in the west to Syria in the east, and while start and end dates are largely a matter of perspective, it existed in the form most people would recognise for over 500 years.

By Ursula Rothe, The Open University

The empire of course had many great strengths – but it could be argued that one of the most important keys to its durability was its inclusiveness.

Come together

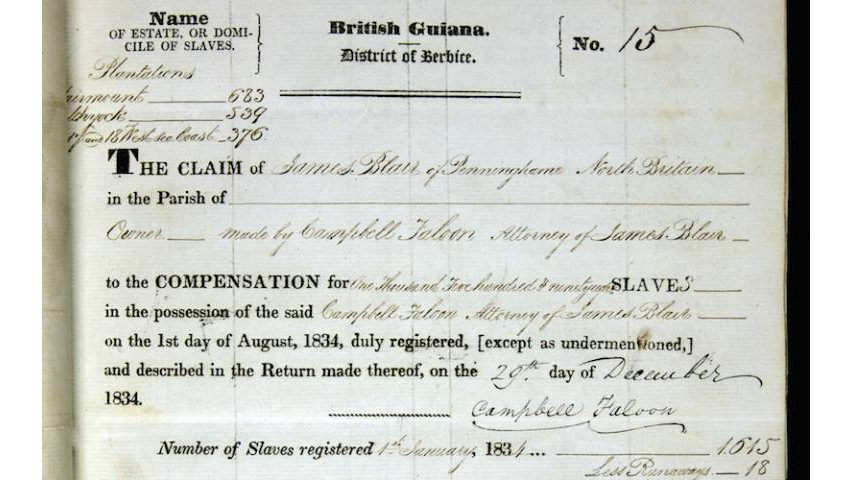

Roman society was, of course, marked by stark inequalities. It was inherently misogynistic and rigidly classed, while slavery was ubiquitous. But in other ways, it was surprisingly open-minded – even by the standards of 2015.

In 48 AD, a discussion took place in the Roman Senate concerning the admittance of members of the Gallic aristocracy to the venerable body.

According to the Roman senator and historian Tacitus, there was opposition to the move; some senators said that Italy was perfectly capable of providing its own members, and that it was enough that northern Italians had been admitted without having to resort to foreigners who had been, until recently, their enemies in war.

But as Tacitus reports it, the then-emperor Claudius championed the move:

My ancestors … encourage me to govern by the same policy of transferring to this city all conspicuous merit, wherever found. And indeed I know, as facts, that the Julii came from Alba, the Coruncanii from Camerium, the Porcii from Tusculum, and not to inquire too minutely into the past, that new members have been brought into the Senate from Etruria and Lucania and the whole of Italy, that Italy itself was at last extended to the Alps, to the end that not only single persons but entire countries and tribes might be united under our name.

We had unshaken peace at home; we prospered in all our foreign relations, in the days when Italy beyond the Po was admitted to share our citizenship…. Are we sorry that the Balbi came to us from Spain, and other men not less illustrious from Narbon Gaul? Their descendants are still among us, and do not yield to us in patriotism.

Everything, Senators, which we now hold to be of the highest antiquity, was once new.

Of course, this account probably doesn’t record precisely what was said on that day; Tacitus often embellished his historical narratives by putting rousing speeches in the mouths of key personalities. But an inscription in Lyon, commonly called the Lyon Tablet, indicates that this address did take place.

And whether authored by Claudius or Tacitus, the content of the speech as recorded shows that 2000 years ago in Rome, prominent figures were putting forward the idea that incorporating citizens from a variety of ethnic backgrounds could strengthen rather than weaken a state.

All for one

By the time of the events described above, for example, Roman citizenship had been extended to large parts of the Mediterranean population and could be acquired by people anywhere in the Roman empire, usually by serving in the army or in regional government. This bestowed the same nominal legal rights on the inhabitants of Egypt and Britain as were enjoyed by the citizens of the city of Rome.

Under the spirit and letter of Roman law, citizenship was generally less a matter of ethnicity and more one of political unity.

Of course, Roman literary sources are hardly devoid of bigotry and cultural chauvinism. But there is little indication in the literature of anything resembling the contemporary view in some circles that bringing in new people represents a threat to national culture or a drain on resources.

Despite substantial evidence both for immigration to Rome from different parts of the empire and geographical mobility within the empire, the impression in the surviving record is of an overriding pragmatism when it came to the adoption of new things and people into the Roman system.

In modern times, as European debates about immigration and diversity take an increasingly emotive and activist turn, there is a real need to bring facts and rational argument back into the fold. And while some sections of the political establishment would hold that a pragmatic approach to immigration will lead “us” into dangerous, unchartered waters, the Roman example shows that this is far from true.

After all, everything of the highest antiquity was once new.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about Roman Empire’s immigration:

Articles you may also like:

Left to ruin: we must preserve our forgotten wartime defences

Reading time: 5 minutes

Australia built a number of coastal defences to help protect the country from any enemy attack during the second world war. Now, almost 80 years later, some of the physical remnants of those historic facilities lie forgotten and decaying.

These monuments to the nation’s home defence are in desperate need of preservation. While their condition varies greatly, too many have faded into obscurity.

The End of History: Francis Fukuyama’s controversial idea explained

Reading time: 8 minutes

In 1989, a policy wonk in the US State Department wrote a paper for the right-leaning international relations magazine The National Interest entitled “The End of History?”. His name was Francis Fukuyama, and the paper stirred such interest – and caused such controversy – that he was soon contracted to expand his 18-page article into a book. He did so in 1992: The End of History and the Last Man. The rest, they say, is (the end of) history.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.