Reading time: 6 minutes

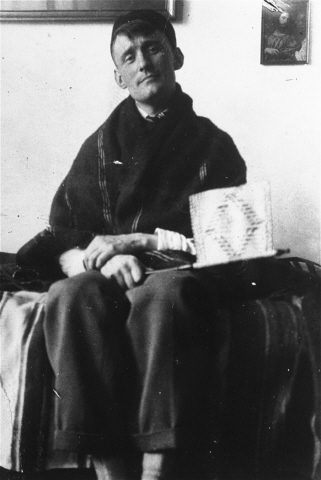

Dutch artist and author Willem Arondeus’ life had always been fraught with insecurity. Despite the modest success of his artwork, he lived in poverty, and friend Frieda Belinfante remembered him first for his timidity. ‘He was very shy,’ she said, ‘and kind of an inferiority complex. He didn’t think he was good enough for this or that.’

By Mye Brooks.

Belinfante believed that Arondeus “felt inferior about his being a gay man,” and such anxieties would have been entirely understandable. Though the Netherlands is often described as the birthplace of LGBTQ+ rights, having decriminalized same-sex relations in 1811, Arondeus still faced discrimination on an institutional and social level. He and his partner, Jan Tijssen, struggled to secure housing, and decades prior, Arondeus had severed ties with his family in an argument over his sexuality. He had only been seventeen.

Still—despite the prejudice of others and his own insecurity—an undercurrent of courageous defiance ran through Arondeus. No matter what, he refused to hide his sexuality. “He was… very obvious,” Belinfante recalled. “I mean, everyone knew it who knew him.”

This resolve was only galvanized in May of 1940, when the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands began. Arondeus wasted no time in turning his artistic skills toward the resistance. ‘He always felt as an outsider,’ remarked Klaus Mueller, a representative for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. ‘But when he joined the resistance, he found his own voice—you see a man who is determined, who knows the risks, but doesn’t feel like an outsider anymore.’

Arondeus joined up with a group of artists and musicians working to establish a mutual aid fund for artists who refused to allow the Nazi Party to dictate the content of their work. He also established an illegal underground publication, called Brandarisbrief, that urged other artists to fight back against the occupation.

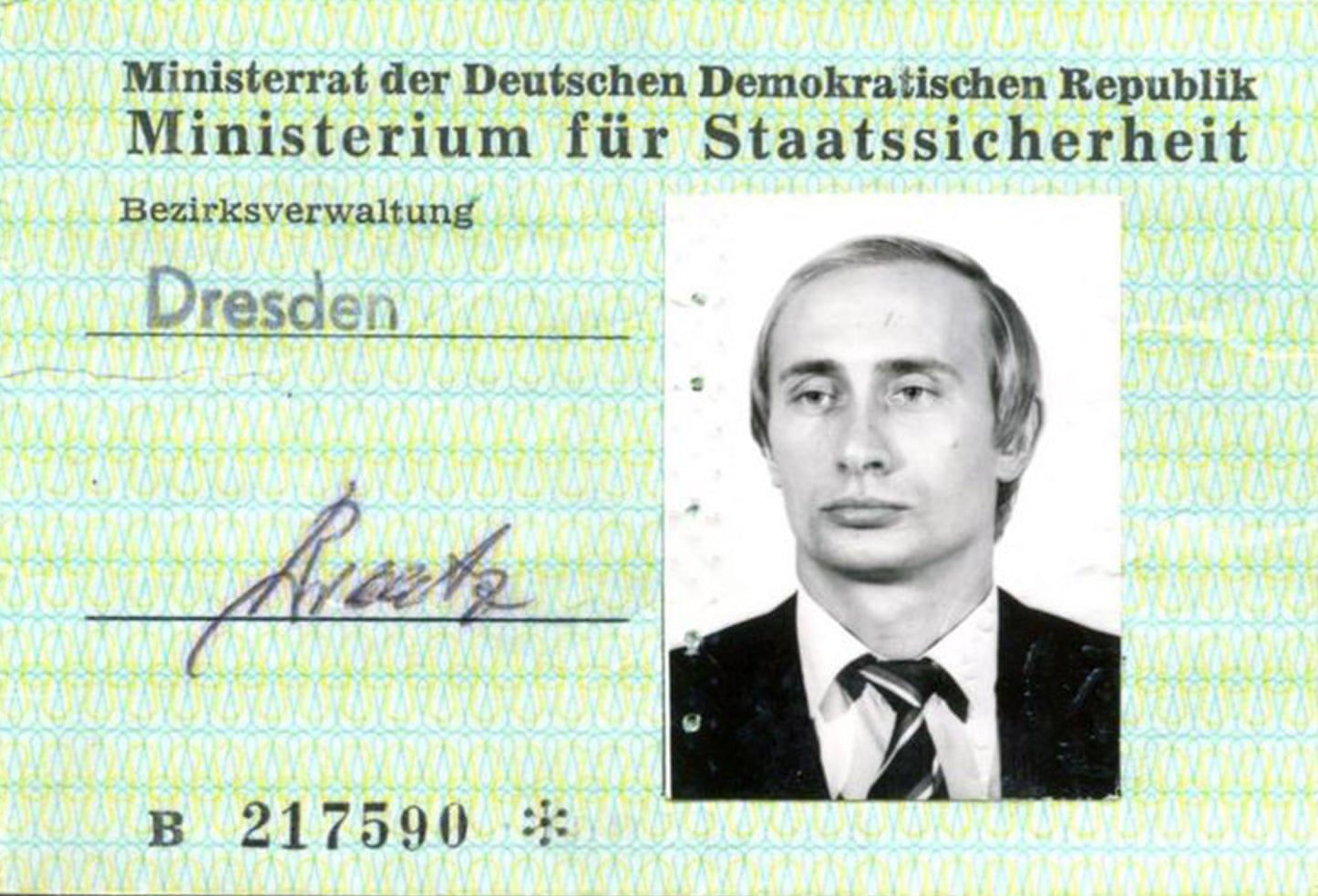

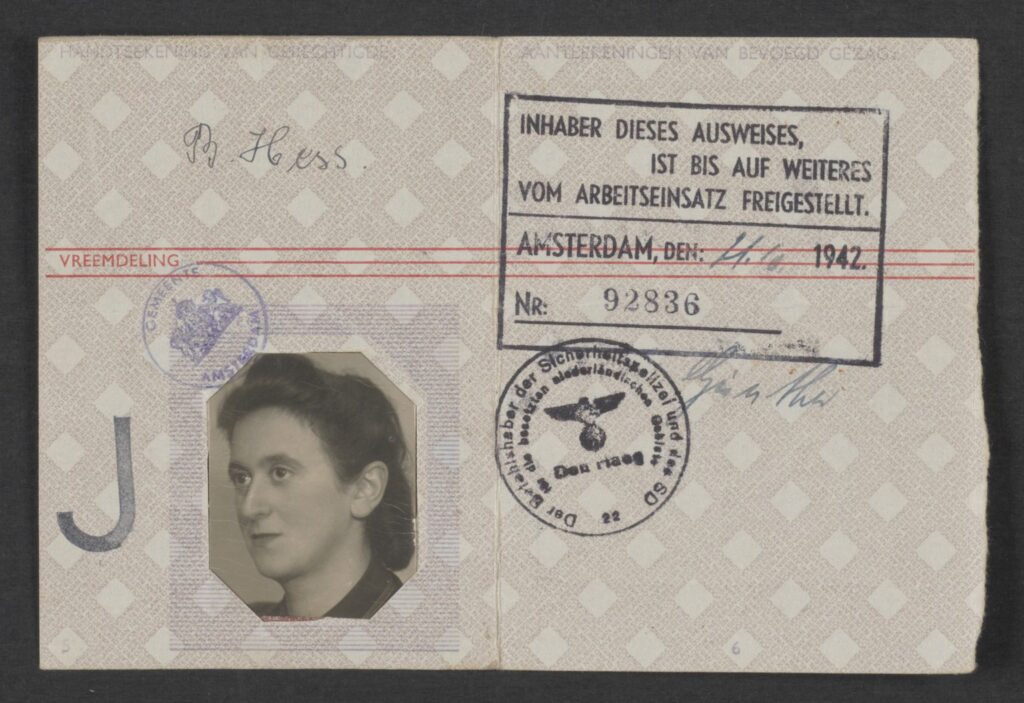

Another facet of Arondeus’ resistance was in the production of forged identity cards. At the time, Dutch identity cards specified whether the card’s bearer was Jewish—a Jewish person’s ID would be marked with a J. Arondeus, Belinfante, and their comrades worked to forge ID cards without the J, so that a person’s Jewish identity could not be discovered by checking their papers. Arondeus’ group fabricated some 70,000 of these lifesaving fake IDs.

Arondeus found great purpose in the resistance and was determined to carry on his work at any cost. He continued even after his partner Tijssen left him in 1941, fearing for his own safety. Belinfante recalls a conversation where Arondeus stated his resolve in no uncertain terms.

“He said ‘do you think that we will see the end of this war?’ and I said ‘I don’t think so,’ and he said ‘I don’t think so either.’ And then he said ‘do you mind?’ and I said ‘no, I don’t,’ and he said ‘I don’t either.’

Arondeus’ fighting spirit was not broken even as the Nazis caught on to the proliferation of false ID cards. When the Nazis began checking ID cards against data available in the Amsterdam public records office, Arondeus and his comrades began planning a counteroffensive.

Over the course of months, the group gathered information. What was the layout of the public records office? What were police uniforms made of? They learned as much as they could, determined to ensure the success of their operation.

This plan finally came to fruition on March 27th, 1943, when a group of Arondeus’ comrades infiltrated the public records office disguised as policemen. They drugged the guards and planted explosives in the archives. Though the ensuing blaze destroyed only 15 percent of the data on file, this amounted to an estimated 800,000 identity cards. It cannot be known how many of those 800,000 were Jewish, nor how many were able to escape the Nazis because of the destroyed data, but the operation was doubtless lifesaving for many.

The attack seemed to have gone off without a hitch. All the saboteurs made it safely home that night. Still, the danger had not passed. Because of their thorough intelligence-gathering, Arondeus and company had involved many people in the development of their scheme. ‘There were so many people involved,’ Belinfante remembered, ‘that it became very dangerous.’

History does not know the name of the person who betrayed the saboteurs, but five days later, Arondeus and several of his co-conspirators were arrested. Still, even when interrogated and tortured Arondeus staunchly refused to sell out his comrades.

Despite Arondeus’ resolve, his notebook was eventually found, and the names of his comrades with it. All those involved in the attack were arrested, save for Belinfante, who escaped by disguising herself as a man.

Those who were arrested were sentenced in a show trial. Some were imprisoned, but Arondeus and others were sentenced to death. On July 1st, 1943, Arondeus was executed by firing squad.

Still, Arondeus was determined that his story should not end with his death. Before his execution, he was able to contact a friend, to whom he relayed his final wish: ‘let it be known that homosexuals are not cowards.’

For many years, however, this wish went unfulfilled. While the bombing of the public records office was celebrated as a heroic act, the LGBTQ+ identities of the saboteurs were hushed up in its narrative. History was unwilling to juxtapose Arondeus’ actions with his sexuality.

This began to change in the 1980s, when Arondeus was awarded the Resistance Memorial Cross, a medal for Dutch people who had resisted the Nazis in World War II. He was also declared Righteous Among the Nations, an honor for non-Jewish people who helped Jewish people survive the Holocaust.

In 1990, a fuller portrait of Arondeus became known to the Dutch public when a biographical television program aired. This program did not shy away from depicting Arondeus as the gay man that he was. After so long, Arondeus’ last wish was beginning to materialize, and Arondeus himself was becoming immortal: a testament to the fact that LGBTQ+ people are capable of great heroism.

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 114

1. How many large ships were sunk during the Falklands War?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

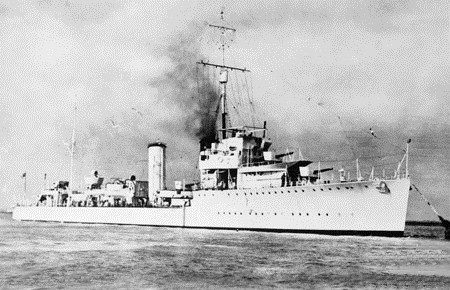

Scrap Iron Flotilla: The Royal Australian Navy at its Best

To the Axis Powers, the Australian flotilla that fought in the Mediterranean during the Second World War appeared to be no threat. Anyone looking at the old, small and slow destroyer group would think the same. Soon, however, the Axis and the rest of the world would learn just how formidable it was. The ‘Scrap […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.