Reading time: 8 minutes

Despite British troops not leaving Egypt until the 1950s, the first Egyptian Revolution actually happened in 1919. Dr John Slight digs into the tensions that united the Egyptian people after the First World War…

By John Slight, The Open University

In 2011, millions tuned in to watch extraordinary scenes of enormous demonstrations in the centre of Cairo against the rule of President Hosni Mubarak, who was forced to relinquish power. The Egyptian Revolution of 2011 was one of the largest components of the wider ‘Arab Spring’, which toppled regimes across the Middle East and North Africa. Modern Egypt is no stranger to revolutions. In 1952, a secret group in the Egyptian Army called the Free Officers launched a takeover of power that heralded the end of royal rule in Egypt, with the banishment into exile of King Farouk, and hastened the departure of British troops from the country after a ‘temporary’ occupation that began in 1882. Gamal Abdel Nasser was the army officer who emerged as President of Egypt and made the country a global symbol of defiance to Western imperialism and a leading power in the Middle East. Yet the first revolution in Egypt in the twentieth century occurred in 1919, when the stresses of the First World War on Egyptian society combined with widespread local hatred of British imperialism in an event that united the Egyptian people.

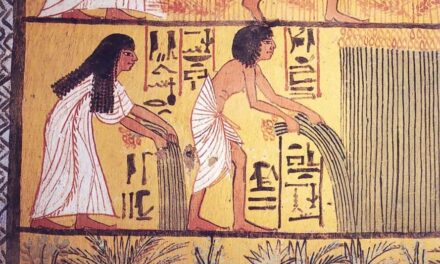

When war broke out in Europe in 1914, Egypt had been under British occupation since 1882. Britain had occupied the country mainly in order to secure the Suez Canal (opened in 1869) a vital strategic artery that was part of the key route between Britain and its vast empire in the East. The occupation was supposed to be temporary, although it lasted until the early 1950s. Egypt formally remained a part of the Ottoman Empire. However, when the Ottomans joined the war on the side of Germany and Austria-Hungary in November 1914, the British felt it necessary to change the status of their occupation. On December 18, 1914, Britain declared Egypt a protectorate of the British empire, deposed the pro-Ottoman Khedive Abbas Hilmi, and replaced him with a relative.

Egypt became an enormous military base for Allied forces, serving as the rear area for the disastrous Gallipoli campaign, and the more successful Allied invasions of Palestine and Syria by the British imperial Egyptian Expeditionary Force.The British authorities imposed martial law on the country, which became a frontline state in the war when Ottoman forces crossed the Sinai Peninsula to try – and fail – to take the Suez Canal. Egypt became an enormous military base for Allied forces, serving as the rear area for the disastrous Gallipoli campaign, and the more successful Allied invasions of Palestine and Syria by the British imperial Egyptian Expeditionary Force. The presence of thousands of Allied troops had a whole series of knock-on effects on Egypt. Many soldiers, especially Anzac troops from Australia and New Zealand, got into fights with Egyptians in cities such as Cairo, often fuelled by alcohol, and often damaged property. So many soldiers created a boom in prostitution, created many (badly-paid) employment opportunities for Egyptians, and contributed to widespread inflation in the Egyptian economy. Thousands of Egyptian men, especially peasants (fellahin) were recruited, often forcibly, into the Egyptian Labour Corps, an organization that received little recognition for its vital role in supporting the Allied armies in Egypt, and on military operations in Palestine and Syria. The labourers were often treated appallingly, and the removal of men from the countryside exacerbated the hardship there caused by wartime inflation, unemployment and the shortage of goods and foodstuffs. Britain had ‘squeezed’ Egypt during the war, but what would Egyptians receive in return for their contribution to the war effort once the fighting had stopped?

Egyptian nationalist politicians such as Saad Zaghlul brought their demands for independence to the British High Commission Reginald Wingate on November 13 1918. They wanted permission to travel to London to press their case and to be included as a delegation at the Peace Conference being planned in Paris. These politicians were drawing from both Egyptian nationalism and the promises made by US President Woodrow Wilson for peoples to enjoy ‘self-determination’. Although Wilson was thinking about Europe, his words went round the world and galvanised anti-colonial movements across Africa and Asia. The British rejected Zaghlul’s demands and questioned how far he represented the Egyptian people. A massive petition showed the level of support he enjoyed. Zaghlul and his fellow politicians became known as the Wafd (delegation) which evolved into a political party. Zaghlul and others were arrested by the British on March 8 1919 and the group exiled to British-controlled Malta.

Egyptian nationalist women played a vital role in organising strikes and boycotts of British goods. The Revolution was a key moment in the history of Egyptian and Islamic feminism.The arrests sparked the Egyptian Revolution. Egyptians from all religions and classes united against the British. Student demonstrations led to strikes by transport workers supported by trade unions, and morphed into a national general strike that paralysed the country. Rioting broke out in Cairo and other places such as Tanta. British forces opened fire on these demonstrations and killed many people. March 15 1919 saw a massive demonstration in support of the Revolution in Cairo, when thousands of Egyptians marched on Abdin Palace. The next day, an even more historic event occurred, when several hundred Egyptian women gathered to protest against the British occupation. Led by the wives of the exiled Egyptian nationalist politicians, Safia Zaghlul, Mana Fahmi Wissa and Huda Sha‘rawi, the women refused to obey British orders to disperse. Sha‘rawi made history again later when she stopped wearing the veil (niqab) in public after her husband’s death in 1922. Egyptian nationalist women played a vital role in organising strikes and boycotts of British goods. The Revolution was a key moment in the history of Egyptian and Islamic feminism.

In the Egyptian countryside, the Revolution was very violent. Peasant resentment against the British, especially in relation to the hardships of the war, exploded into violent actions. Railway tracks and telegraph lines were sabotaged. British soldiers and civilians were killed, along with Egyptian officials and others who collaborated with the British regime. The British effectively lost control of most of Egypt during March 1919. This situation was reversed by General Bulfin, who organised ‘flying columns’ that brutally suppressed the Revolution in the countryside and regained control over Egyptian towns in a campaign of terror. Wingate was replaced by war hero General Allenby as High Commissioner, who realised that negotiations were necessary as Egypt could not be held by military means indefinitely; he swiftly released the Egyptian nationalist politicians. Their release, and British permission for them to travel to Paris for the Peace Conference, led the politicians to sign a letter calling off the demonstrations.

The British faced a difficult question: how could they deal with Egyptian demands for independence but maintain their interests in the country – military, strategic, and economic? British statesmen Lord Milner was sent to Egypt in December 1919 to find a solution but was faced with strikes and unrest. Milner brought Zaghlul and his associates to London for talks and in 1920 won the condition that the abolition of the British protectorate was a prerequisite for further negotiations. This elevated Zaghlul’s standing in Egypt even higher. But Allenby’s concerns over Zaghlul’s popularity led to another deportation, this time to the Seychelles, in December 1921. Strikes and demonstrations ensued. The British decided to proceed with their plan for Egypt without consulting Zaghlul and nationalist politicians. Egypt was declared an independent country on February 28th 1922. But the situation on the ground suggested this independence was limited. Britain retained control over Sudan, formerly an Egyptian colony, as well as control over Egypt’s defence and foreign affairs. Foreign interests in Egypt, notably its large European community, were maintained by the British. British troops remained stationed in Egypt, and Britain reserved the right to increase troop levels during a state of war.

The events of 1919 in Egypt show how the First World War played a crucial role in affecting the country’s history after the war ended.The interwar years saw a political dance take place between the British, Egyptian nationalist politicians, and the Egyptian king, who mistrusted the nationalists. It would take the upheaval of the Second World War and a further Egyptian Revolution in 1952 for the British to leave Egypt. The last British troops left in June 1956, although the Suez Crisis later that year saw their temporary return. While the Egyptian Revolution of 1919 did not secure Egypt’s freedom from foreign rule, it was an important step towards that goal. After 1919, the British had to consider the strength of Egyptian nationalism and deal with nationalist politicians. The Revolution was an inspiration for other anti-colonial struggles across Africa and Asia. The events of 1919 in Egypt show how the First World War played a crucial role in affecting the country’s history after the war ended. The negative effects of the war on Egypt unleashed powerful forces in Egyptian politics and society that could not be ignored.

This article was originally published by The Open University.

Podcasts about the Egyptian Revolution 1919

Articles you may also like

How They Fought: Indigenous Tactics and Weaponry of Australia’s Frontier Wars – Book Review

Reading time: 3 minutes

This is an excellent and much needed book. It examines the military aspects of the Australian Frontier Wars from an Aboriginal perspective, detailing the tactics, strategy, logistics and weapons Aboriginal people employed to resist European encroachment on their land. Covering several campaigns across different areas and time periods, it details both successes and failures of the Aboriginal military forces. Some of its most interesting conclusions reflect the extent to which Aboriginal resistance slowed and impeded the encroachment of European settlement across Australia.

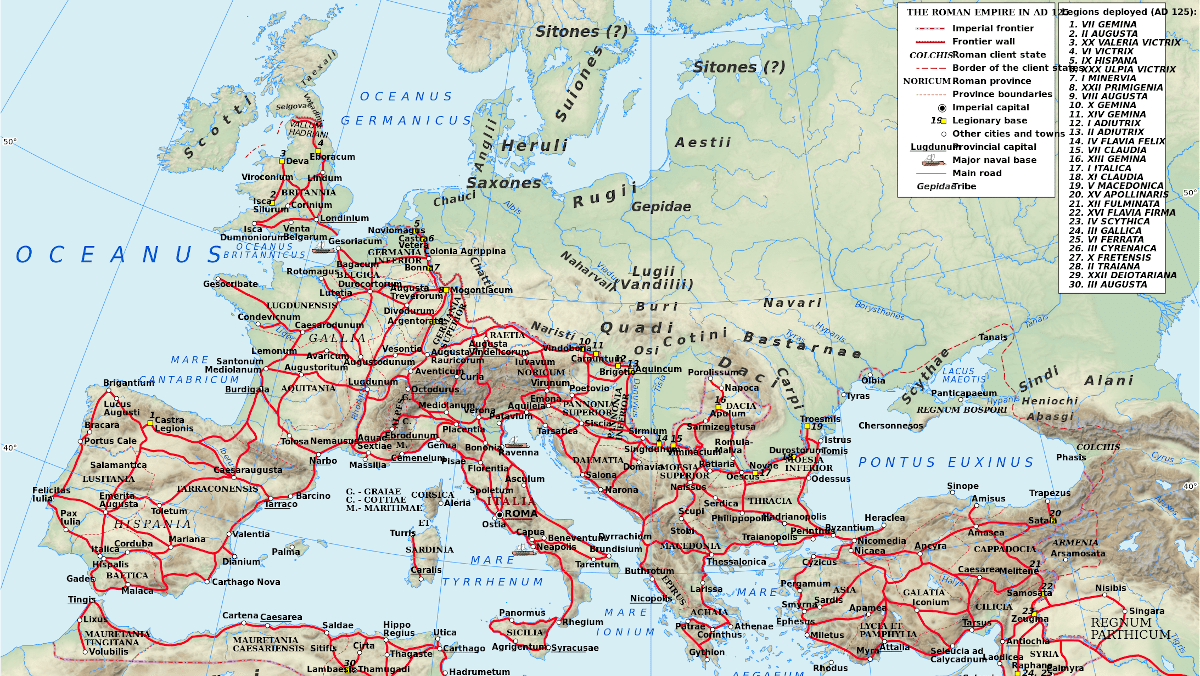

Does the Roman road network influence European prosperity even today?

Reading time: 5 minutes

If there’s one thing the ancient Romans are famous for, its their roads. The empire was criss-crossed with them, mainly to quickly shuttle the legions about, but they also facilitated trade. We know this network survived the collapse of the empire, but could it influence the European economy to this day?

Bismarck and the Origin of the German Empire – Audiobook

BISMARCK AND THE ORIGIN OF THE GERMAN EMPIRE – AUDIOBOOK By Sir Frederick Maurice Powicke (1879 – 1963) Despite its brevity, this Little Blue Book #142 by the Oxford historian, Sir F.M. Powicke, provides a valuable overview of the political history of Germany from medieval to modern times, culminating in the career of Otto von Bismarck […]

The text of this article is republished from The Open University and is is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.