Unearthed secrets from 7,000 years ago highlight prehistoric women as the heroines who dug deep–quite literally, to plant the seeds of the first Agricultural Revolution–a recent study in Science Advances has unearthed. Analysis of the bones of these women shows they took on their fair share of digging, hauling, hoeing, and grinding grain in early agricultural societies – in fact, so much so, that their upper body strength would have been greater than that of modern female athletes today. Notably, these findings disprove the widely-held notion that prehistoric women favored domestic tasks over intensive manual labor.

By Jennifer Short.

Women took on their fair share of manual labor

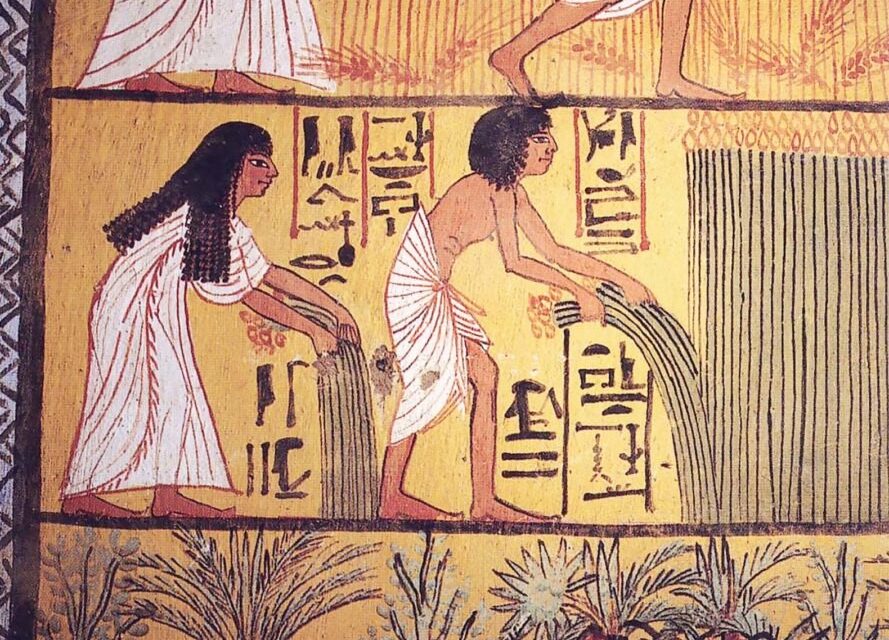

Prehistoric women possessed remarkable physical prowess, with arm strength surpassing that of today’s elite female athletes by 5% to 10%. Their muscular power, particularly in terms of pull strength, is comparable to contemporary champion rowers–according to recent research findings. Although it’s difficult to say for sure, it seems prehistoric women were therefore no strangers to tasks like grinding cereal grains, digging ditches, and lifting and carrying crop baskets and equipment during the first Agricultural Revolution. The intensive cultivation of cereals, such as, einkorn, barley, club wheats, spelt, millet, and emmer, was a particularly vital task in the Early Neolithic of Central Europe. The findings show prehistoric women were likely involved in tilling, planting, and harvesting crops with hoes, flint sickles, and digging sticks, as well as grinding grain once harvested. Indeed, farming first arrived in the United Kingdom at the dawn of the Neolithic period around 6,000 years ago, and there’s plenty of prehistoric sites across the country today that provide insight into our vibrant Neolithic past. The Calderstones, in particular, are a group of six megaliths and the awe-inspiring remains of a Neolithic tomb built over 5,000 years ago.

Bones: shining a light on the past

“People haven’t typically focused on females in this society, [but] it’s very important for understanding … the divisions of labor that exist today,” says Hila May, an anthropologist at Tel Aviv University in Israel. “I wish we could go back and ask people how they lived, but all we have is bone.” In the study, 89 shin bones and 78 upper arm bones from women who lived during the Neolithic (5300 B.C.E.–4600 B.C.E.), Bronze Age (3200 B.C.E.–1450 B.C.E.), Iron Age (850 B.C.E.–100 C.E.), and Medieval (800 C.E.–850 C.E.) periods in Central Europe were analyzed with a 3D laser imaging system. Additionally, athletic female college students – experienced rowers, runners, and soccer players – from the United Kingdom also participated in the study, while physically active students who aren’t athletes were also recruited. The leg and arm bones of the study participants were then x-rayed with a computerized tomography scanner.

It’s normal for bones to change shape, twist, and elongate over the years due to repeated strain and movement. As such, the end of the nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle in favor of the adoption of permanent settlements roughly 10,000 years ago can be seen in skeletal remains. For instance, researchers note that shinbones belonging to central European men between 5300 B.C.E. and 100 C.E. became notably straighter and less rigid as people embraced farming over roving. Women’s shinbones, on the other hand, don’t show much change at all during this same time period. In the past, researchers put this discrepancy down to the likelihood of prehistoric women favoring domestic tasks that don’t require much physical strength. However, study author and anthropologist at the University of Cambridge, Alison Macintosh, wasn’t satisfied with this explanation. “We felt it was likely a huge oversimplification to say [prehistoric women] were simply not doing that much, or not doing as much as the men, or were largely sedentary,” she says. In particular, the researchers analyzed bone shape – which indicates how much muscle was present – before then comparing the bones to those of prehistoric women in the years prior. That’s when it was determined that, while leg strength remained largely the same over the years, women’s upper body strength increased over the first Agricultural Revolution. Analysis of the bones of prehistoric men, on the other hand, indicates they typically participated in a mixture of farming and lower body–intensive tasks like hunting and running.

“The findings are convincing and may help explain why bone diseases such as osteoporosis are so common in women today” says anthropologist Hila May. “Evolution may have shaped women’s bone structure to deal with the stresses of life on the move during hunter-gatherer times, and the rapid shift to a more stationary, farming-focused life might have led to weaker bones”. Now, future research aims to hopefully shed light on just how prehistoric men and women divided chores and manual labor during the first Agricultural Revolution.

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 49

The History Guild Weekly History Quiz.See how your history knowledge stacks up. Have an idea for a question? Submit it here and we’ll include it in a future quiz! Please leave this field emptyTell me about New Quizzes and Articles Get your weekly fill of History Articles and Quizzes First Name (Optional) Last Name (Optional) […]

Putin’s failure to learn from history has led to Russian quagmire in Ukraine

Reading time: 4 minutes

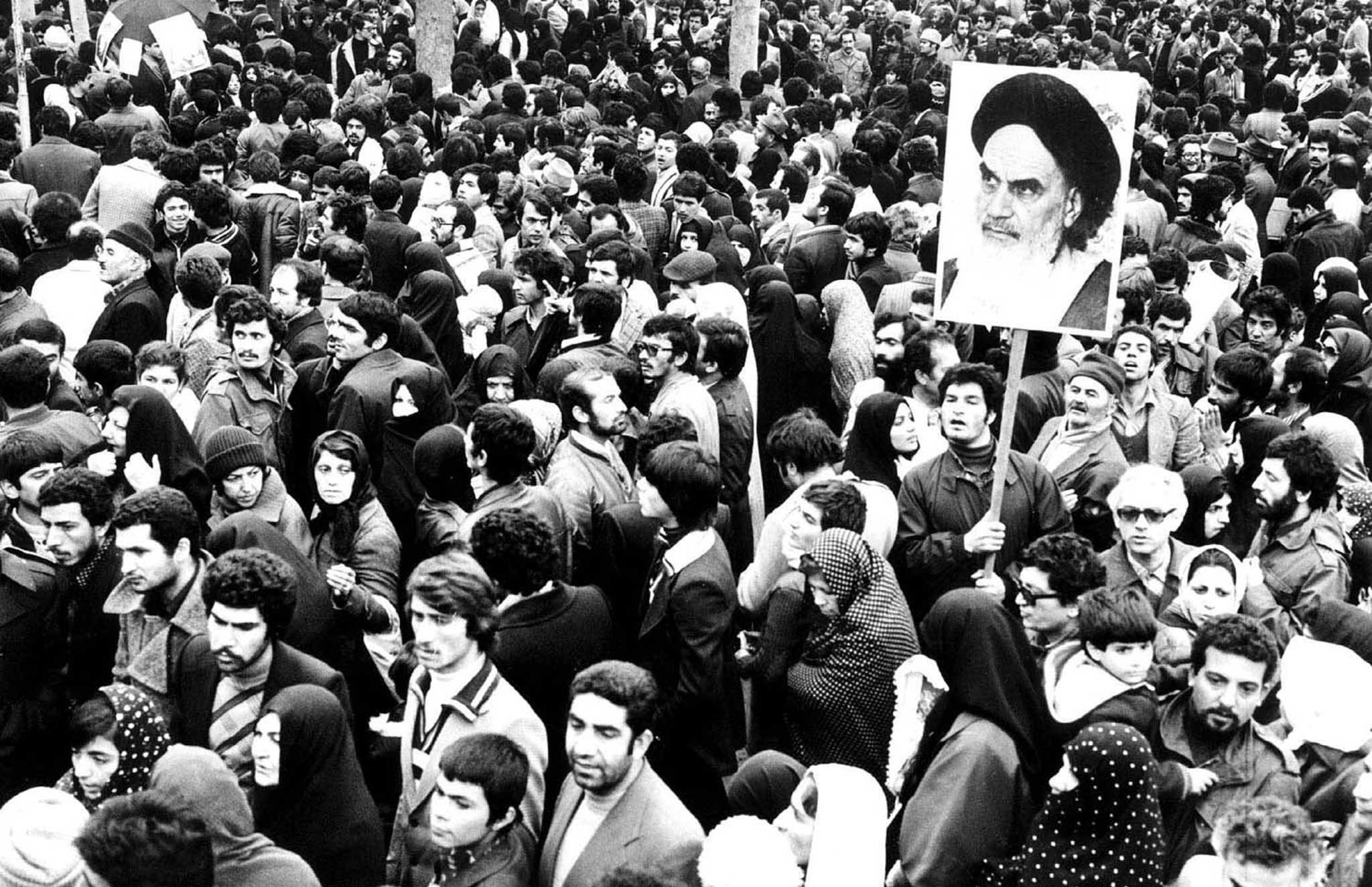

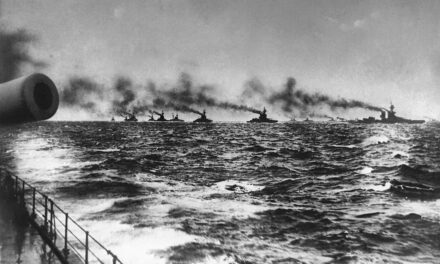

As the Russo-Ukraine conflict continues with no resolution in sight, we are painfully reminded of not only the horror of war, but also how often major powers’ interventionism, for whatever objective, hasn’t paid off. These powers have repeatedly failed to learn from the futility of their past adventures to avoid future ones. Counterproductivity has often become the hallmark of their efforts.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.