Reading time: 6 minutes

The Sino-Vietnamese war was a short, nasty conflict fought between China and Vietnam in early 1979. Largely forgotten by almost everybody including the belligerents, it was a side plot of the Sino-Soviet split, itself a sideshow to the Cold War. Let’s go over the events before, during and after the war to see what it was all about.

By Fergus O’Sullivan

Vietnam and China have a long history of conflict, but the Sino-Vietnamese war of 1979 is a little different. For one, it was short, lasting less than a month, and its goal was, well, a little murky. Depending on how you interpret events, you could call it a successful punitive expedition, a failed invasion or something else entirely.

The War In Context

What most historians agree on, though, is that the war is part of two other important historical movements: the Sino-Soviet split, which saw the two largest communist powers at each other’s throat, and the Indochina wars. Many historians will call this conflict the Third Indochina war, where the uprising against the French was the first and the war between North and South Vietnam was the second.

When studying these conflicts, the focus is usually on Vietnam: of the countries in South-East Asia, it’s the largest and most populous. It’s also the most famous, simply because the Americans fought there and they made many historical films depicting events there. However, there was fighting all over the area, including between the countries themselves.

The fight that sparked Chinese intervention was the invasion of Cambodia by Vietnam. Though the intentions of Vietnam weren’t entirely humanitarian in nature, it should be noted that the invasion ended the regime of Pol Pot, the madman who ran Cambodia from 1976 to 1979 and had at least 1.5 million of his countrymen murdered during that time.

Ties That Bind

Of course, you may wonder why China even cared about Vietnam invading Cambodia: this is where the Sino-Soviet split comes into play. Over the years between the death of Stalin — and particularly of Krushchev’s denunciation of the crimes perpetrated by the man of steel’s regime — the once warm relationship enjoyed by the two great communist states had cooled considerably.

In fact, what it had grown into was a little cold war all of its own between the two, with other communist states drawn into the orbit of one or the other. Due to China’s small geopolitical reach — in contrast to now — this battle was mostly fought in China’s backyard, Mongolia in the north and Indochina in the south.

In this mini-cold war, Laos and Cambodia’s regimes were backed by the Chinese, while Vietnam received help from the Soviet Union. It should be noted that though China offered some help, most of the firepower the Americans faced in Vietnam was supplied by the Soviets.

Naturally China wasn’t too enthused by having a Soviet-friendly country right next door, and having it then invade a friendly country and depose its leader especially irked Deng Xiaoping, the Chinese communist party chairman.

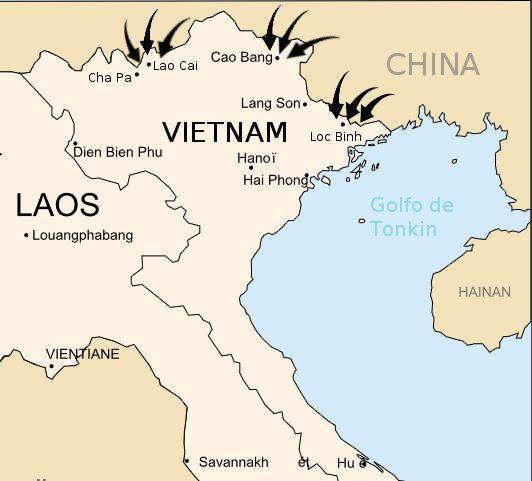

Vietnam was warned several times to knock it off, but, trusting in their powerful benefactor’s protection, they went right ahead and continued military action against Cambodia. This spurred China into action, and it invaded on February 7th 1979. The goal, ostensibly at least, was to force Vietnam to leave Cambodia.

The War Starts

The Sino-Vietnamese War of 1979 is often described as a border war, mainly because the fighting didn’t go more than a hundred kilometres from the border between the two countries, and it’s surprising how few men China committed to the fight. Figures are contested, but it was somewhere between 200,000 and 500,000 soldiers.

The reason it only brought limited force to bear was because the rest of its massive army was up near the Russian and Mongolian borders, to meet an invasion from the Soviets who may or may not come to their ally’s aid. Also, there seems to have been some hubris on China’s part. The regular Vietnamese army only had about 100,000 or so men under arms, meaning that even with the lowest estimates the Chinese had a serious advantage.

What the Chinese didn’t count on was Vietnam’s massive irregular forces, hardened by years of fighting the U.S. in the jungles of the south. It’s odd that Beijing made such a vital miscalculation, because the Americans had fallen into the same trap just a few years previously.

Guerrillas in the Mist

Unsurprisingly, the Chinese ran into trouble almost immediately. According to Chinese sources, the goal was to capture a few cities near the border to show they meant business, and then withdraw, or maybe maintain a small, limited occupation; it’s a little unclear.

However, the fighting turned out to be a lot tougher than expected, and progress was very slow. The Vietnamese had little interest in fighting a stand-up war, and fought guerrilla campaigns that focused on slowing down the invaders more than anything, and then bleeding them with pinprick attacks.

As a result, the The Chinese People’s Liberation Army was able to capture its main objectives, the cities of Cao Bằng, Lào Cai and Lạng Sơn, but ended up needing a lot more men than they expected, and every step ended up being fought for. Realizing they would probably die a death of a thousand cuts, they declared victory and retreated across the border. That’s one way to end a war, I guess!

With the Chinese retreat on March 6, 1979, the Vietnamese, in turn, declared a victory of their own and threw a big party across the country.

The Vietnamese take is honestly a little more believable as they quickly reoccupied their own territory and Vietnamese forces would remain in Cambodia another ten years, which was very much against China’s wishes.

Though the winner may be in dispute, there is no question of who the losers were: the war cost the lives of 50,000 to 100,000 people, depending on who you believe. Whatever the real figure may be, it seems that they paid a very high price for China’s power politics.

Podcast Episodes about the Sino Vietnamese War

Articles you may also like

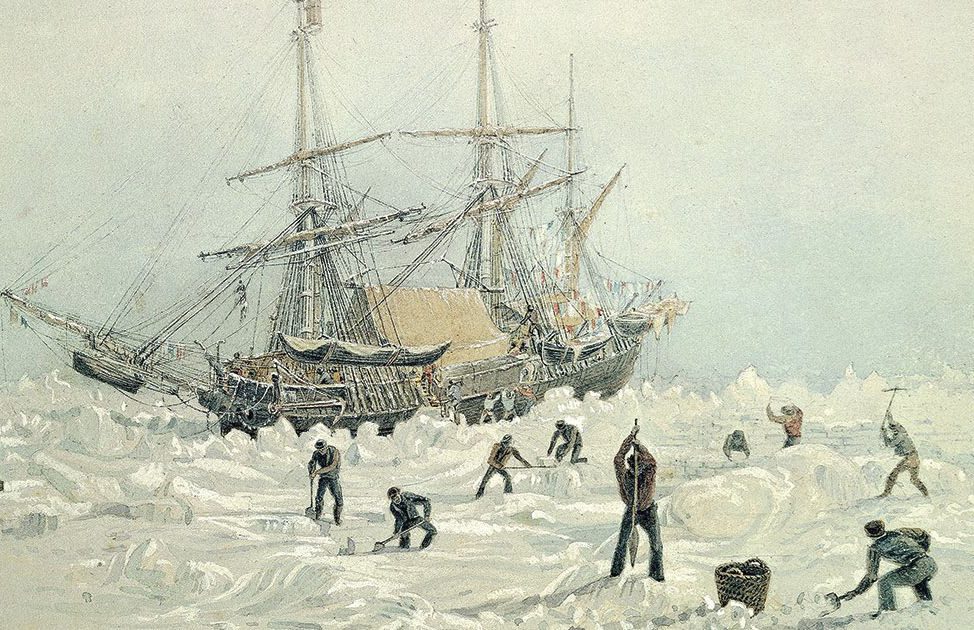

HMS Terror wreck found – but what happened to her doomed crew? Here’s the science

It remains one of history’s best-known naval tragedies – and mysteries. The loss of all 129 men of the 1845 Royal Navy expedition led by Captain Sir John Franklin to navigate a north-west passage through the Arctic remains an enigma. The only informative document to be recovered from the expedition was a single page that reported initial […]

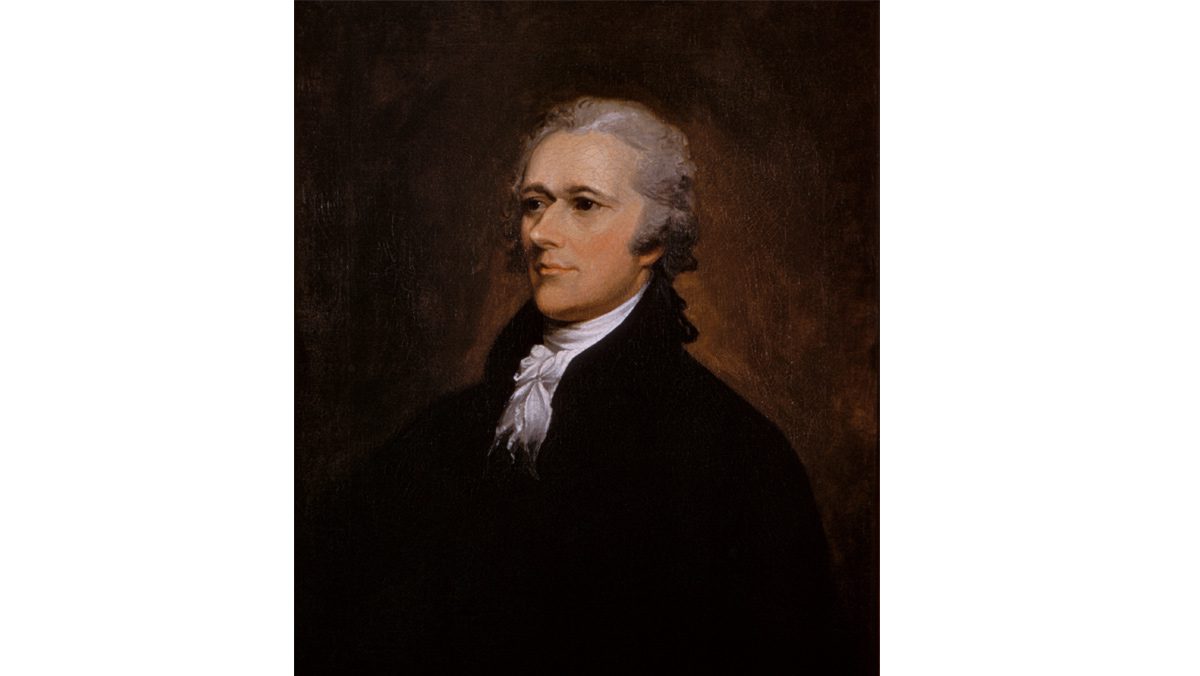

Alexander Hamilton – Audiobook

Alexander Hamilton was a significant figure in the political and economic development of the early United States. He served in the American Revolutionary War and became an aide to General George Washington. One of the authors of The Federalist Papers, which were written in support of the ratification of the proposed Constitution. The Federalist Papers are still referred to when interpreting the US constitution.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.