Reading time: 6 minutes

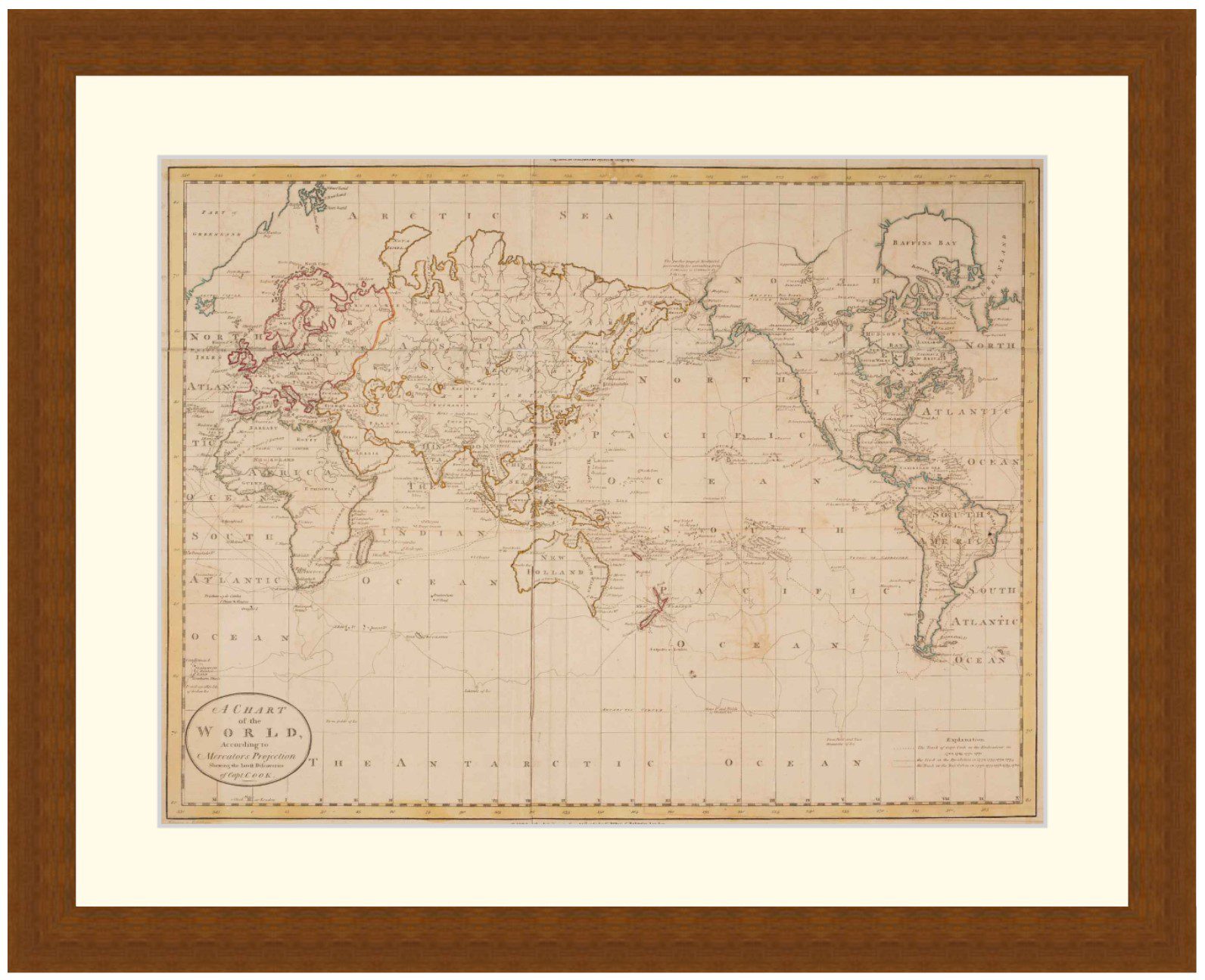

The Cold War had a lot of strange alliances, with many unlikely partners like Australian intelligence service helping overthrow Chile’s elected government or the United States selling weapons to Iran. Weirder still, a natural alliance, one between the communist behemoths of the Soviet Union and China, never really worked out. What was behind the Sino-Soviet split, and how did it lead to China and the United States working together against the Soviet Union?

By Fergus O’Sullivan

Relations between the communist parties of the Soviet Union and China started out amicably enough. After the Russian Revolution, the Soviet communists formed the Communist International in 1919, better known as the Comintern. The goal of this organization was to spread the revolution across the globe and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were happy to join.

Ideological differences

However, there was some friction from the start: as a primarily agrarian economy, mainstream Comintern thought held that China wasn’t ready for a revolution since in Marxist-Leninist theory you need an urban proletariat to throw off their chains. Mao Zedong, the Chinese Communist leader, countered this with his idea of the peasant’s revolution, an idea that didn’t gain much traction in Moscow.

This may explain the lukewarm support the CCP received in their ambitions. When the Chinese empire collapsed, the Soviet Union threw its weight behind the nationalist Kuomintang (KMT), and pushed the CCP to accept a junior position. Moscow never really supported the CCP in any of its ambitions until the late 1940s, when they seemed almost sure to win.

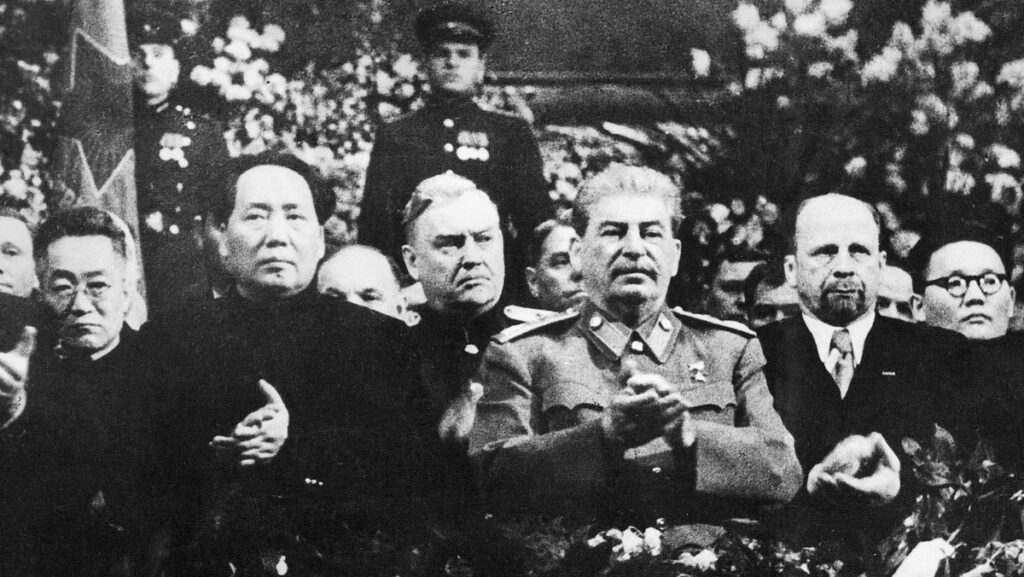

Even then, though, Stalin, the Soviet leader, didn’t seem too impressed with Mao and his peasant revolution. When the two met in 1949 to sign the Treaty of Friendship, Alliance and Mutual Assistance between the two countries, Mao was left to wait for days while everybody prepared for Stalin’s 70th birthday party. So much for international brotherhood.

Stalin also wasn’t too impressed with China’s actions during the Korean War and only helped his fellow communists on the sly. Worse yet, according to Chinese scholars Chen Jian and Yang Kuisong, China was made to pay for the support that it did get.

Trading humiliations

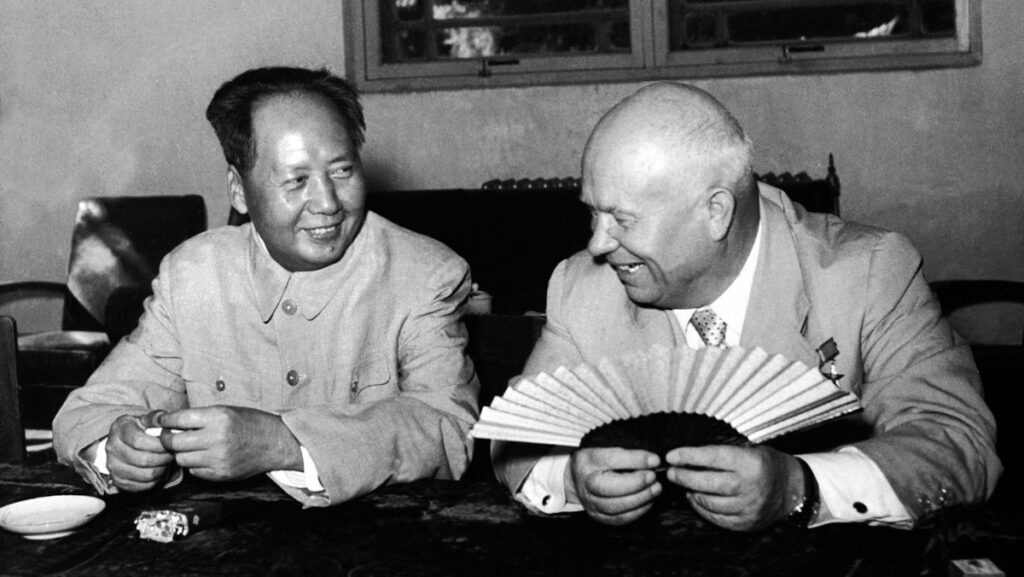

All this rankled Mao, and when Stalin’s successor, Nikita Khrushchev, visited Beijing in 1954, the Chairman took some petty revenge. Besides being rude to Khrushchev whenever he could he also arranged for one meeting at his private home, which had a pool. Knowing Khrushchev couldn’t swim, Mao arranged for a child’s floaties for the Soviet leader. Meanwhile Mao, an avid swimmer, literally swam laps around him.

The bad blood between the two leaders was compounded by ideological differences in 1956, when Khrushchev condemned Stalin’s terror in the Secret Speech 1956. For the details we recommend this detailed record of the ideological back-and forth, but the short version is that the CCP felt that unveiling Stalin’s crimes hurt the cause — an unsurprising position from a man as bloodthirsty as Mao.

The CCP also saw Khrushchev as pandering to the West with his policy of peaceful coexistence with the U.S. and even accused him of weakness during the Cuban Missile Crisis, one of the biggest breakpoints of the cold war. In reply, the Soviet Union discontinued aid for the Chinese nuclear weapons program in 1959 and even expressed sympathy for the Tibetans when they rose up against Chinese occupation in that same year.

On paper, though, the countries were still somewhat friendly, even just because they shared the same ideology. However, that changed in 1960 with the Soviet Albanian split, where the CCP explicitly expressed support for the Enver Hoxha and his breakaway ideas. From this point, it seems relations broke down completely.

A cold war heats up

A good example of how Moscow turned away from Beijing too place during the short but nasty Sino-Indian war of 1962. The Soviet Union was initially neutral, but then came down in support of India, supplying weapons to the enemy of their ideological brethren. This turned this spat in the high Himalayas into a proxy war of sorts.

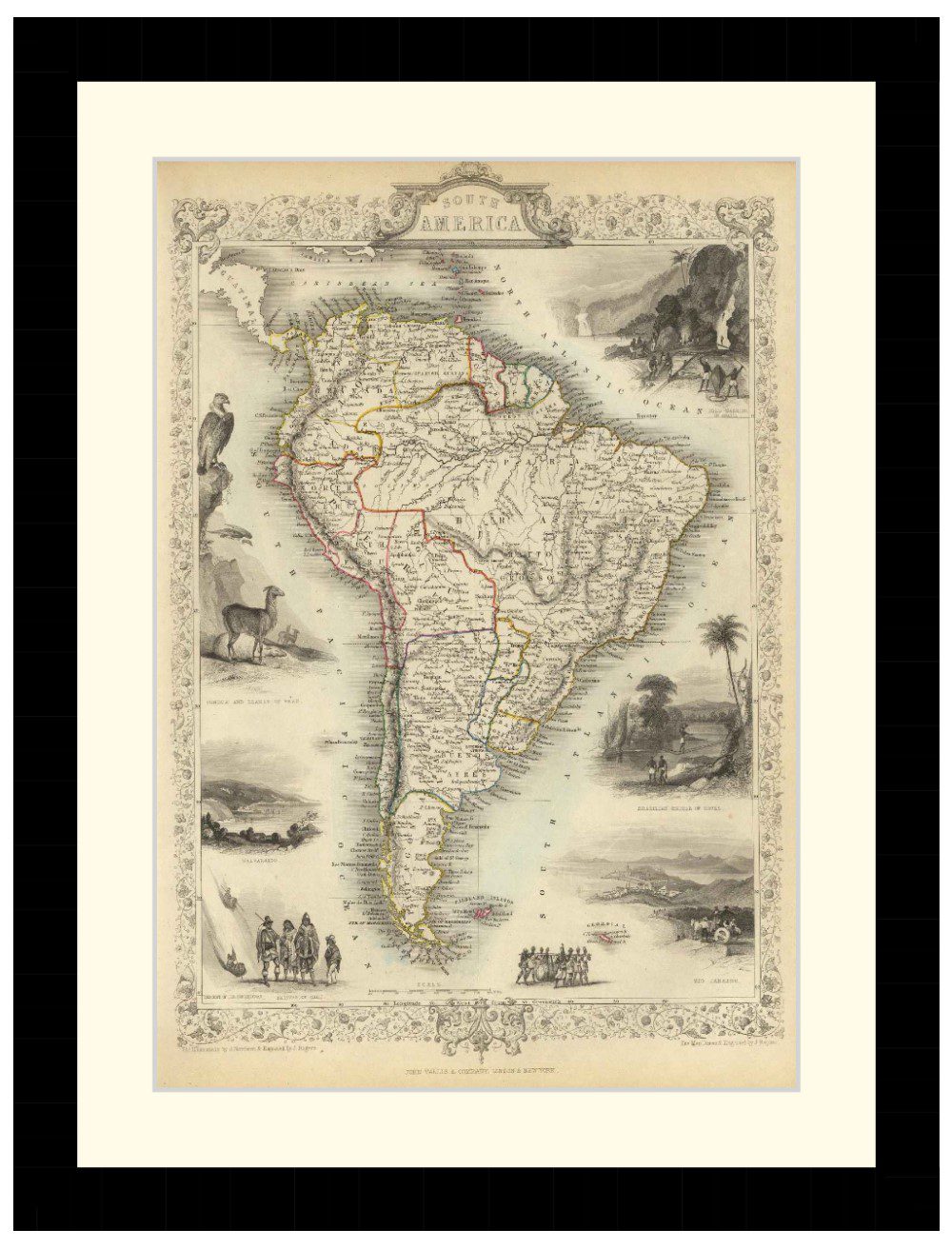

China wasn’t content with restricting the fighting to proxies, though, and in 1969 initiated a number of border clashes in Xinjiang province, in the country’s far West. The stakes were several uninhabited islands in the Ussuri river, which has formed the border between the two countries since 1860.

Over the course of several months Chinese and Soviet troops ambushed each other in nighttime raids in an undeclared war that always was at the tipping point of turning hot. Somehow it was kept cool enough to keep from boiling over, but several times the world was close to a superpower war — one without U.S. involvement.

Eventually things did settle down in Xinjiang, but relations between the Soviets and the Chinese didn’t recover. In fact, China would invade Moscow’s direct ally Vietnam in the Sino-Vietnamese war of 1979 when it attacked Beijing’s puppet regime in Cambodia. The war is claimed a win by both sides, but it was a very clear move by the CCP to show it was to be respected.

In that same year, a new challenge emerged with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. China saw this as an attempt to encircle the Middle Kingdom and decided to aid the mujahedeen with guns. In a reversal of expectations not found outside of the Cold War, China even received military aid from the United States to do so.

One communist state turning on another, then invading a third communist state which was at war with a fourth one, before allying with the capitalist enemy to help guerrillas fighting a communist invasion thousands of miles away, all in one year. It’s cold war madness at its peak.

This little cold war would eventually last until 1989 when Soviet leader Gorbachev visited to mend fences. However, within two years his regime had collapsed as well, making China the only communist superpower. Looks like there was a winner after all.

Articles you may also like

Remember El Alamein

Reading time: 5 minutes

Exactly 75 years ago, Australians dressed in steel helmets and khaki shorts, and often not much else, sat in weapon pits in the Egyptian sun about 120 kilometres west of Alexandria. They were preparing for what history would call the second battle of El Alamein, the great offensive planned by Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery. In the summer heat of July 1942, his predecessor, Archibald Wavell, had held the German–Italian drive towards Egypt, a battle in which the 9th Australian Division had played a notable part. Now, after gathering more troops, tanks and guns, Montgomery was ready to launch his Eighth Army against General Erwin Rommel’s Panzer Armée Afrika, a commander and a force admired and respected even by their adversaries.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.