Reading time: 5 minutes

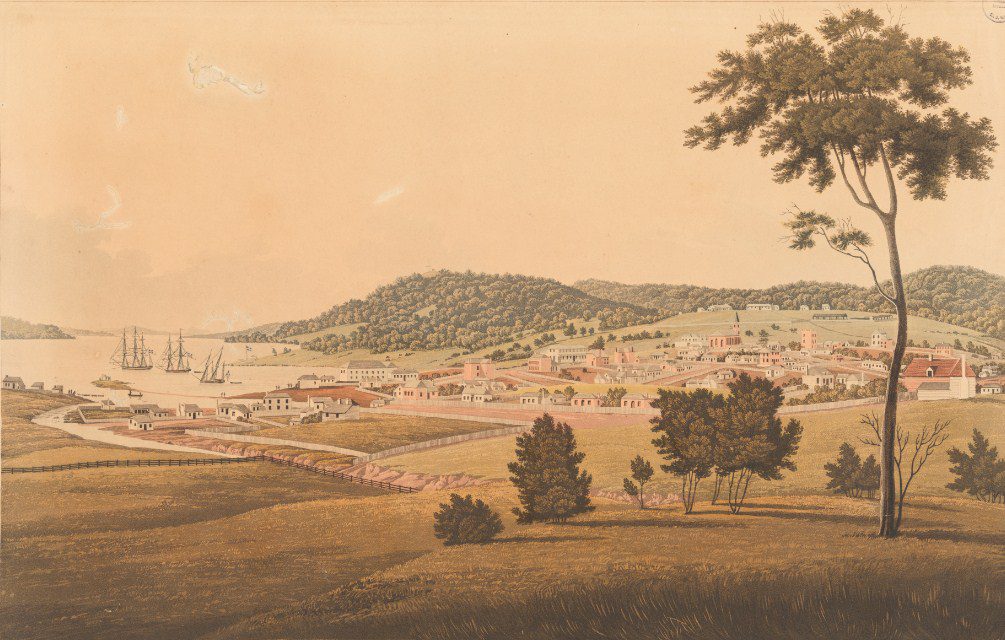

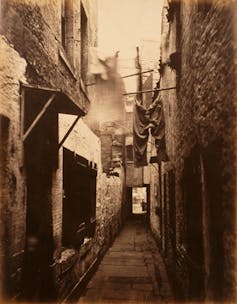

As well as being Scotland’s largest city, Glasgow was its industrial heart. Central to the civic story, is the River Clyde, famed as a global shipbuilding hub in the 20th century. But the Clyde, along with an abundant supply of coal, also made Glasgow the ideal location for the textile industry. In the 1820s, spinning mills, weaving mills, dye houses and garment factories sprang up, dominated the urban landscape.

Access to the public sphere and the professional world had been the prerogative of men in the 1800s. But the textile industry presented an opportunity for women. From the introduction of automatic looms and sewing machines, machinery became less physically demanding to operate. That gave women an advantage, and in Glasgow, they began to step out of their homes to claim a place on the factory floor.

By Fanette Pradon, Université Grenoble Alpes (UGA)

Men remained dominant in managerial positions. Women were paid on average between one third and one half of what men earned. In response, Glasgow’s pioneering female workers began a struggle to profoundly change the conditions for women living and working around the world. It would take decades, but they eventually enabled their fellow women to gain visibility and greater rights, both in the workplace and throughout society.

I have been sifting through research and documents as part of my doctoral studies and they reveal more about the attitudes and barriers these groundbreaking women faced. Such insight into these lives makes their achievements all the more remarkable.

As Glasgow’s textile industry expanded in the 1800s, women represented a rising percentage of the workforce. As the municipal archives show, the city had 403,120 inhabitants in 1861, 58% of whom were women. Of these, 65% were working women, the majority of whom were employed by the textile industries. They came to be seen as a plentiful supply of cheap labour and were, as historian Judith Walkowitz has said, the “symbol of industrial exploitation”.

Factory work and sexuality

The association of women and machines was in itself controversial and prompted a fierce debate. As women shifted into factory work, they were forced to use looms and other machines for up to 12 hours a day, with repetitive gestures. They became, in the eyes of the male supervisors and foremen, “machine women”, bewitched and disembodied. And when femininity was associated to this strangeness, it elicited fear in men. The men came to think of themselves as inquisitors and the machine became the pillory, with women condemned to subordination.

These automaton women still possessed a glimmer of humanity, as men in power at the time saw it: their sexuality. For seamstresses, this was expressed by the perpetual movement of the legs and foot on the pedal. Doctors thought this use of the pedal could induce hysteria and excitement in women. The French deputy Charles Benoist wrote in 1904 that mixing men and women in the mills of France and Britain, combined with the lack of privacy, the heat of the coal-fired boilers and the ambient humidity, would exacerbate passions.

The scientific community at the time believed women lacked the imagination needed for tasks that were creative or that required a high level of finish. Women were thus forced into unskilled jobs with little responsibility, and their access to training was limited. To ensure discipline – and to protect men from temptation – factory owners implemented a strict division of tasks according to gender and put female workers under close supervision. They were not, under any circumstances, to be distracted from their work.

The owners and operators of mills thus sought to control women in every way – not just physically and professionally, but also morally.

The struggle for women’s rights

Glasgow’s textile industry began to decline with the outbreak of the American Civil War (1861-65). The United States was the sole supplier of cotton to the city’s textile industries, and the conflict led to a breakdown in trade and bankrupted many companies.

As the industrial context became more difficult, working conditions for women worsened. The workplace was competitive, with job insecurity and financial strain. Because men continued to monopolise skilled positions and dominate the management structure, when sexual assaults occurred, women were often reluctant to testify for fear of being dismissed.

Victorian society did not recognise sexual harassment, and male integrity was assumed and protected. If women did speak out, their aggressors were most often left unpunished and the fault assigned to female worker and her inherently provocative nature. After all, if such acts occurred in the workplace, how could they really be sexual harassment?

But as early as the 1860s, women workers in Glasgow’s factories began to fight back. The decline of the textile industry exacerbated unemployment and economic difficulty, and working-class women joined forces with middle-class feminists in demanding gender equality at work. In 1883, the Co-operative Women’s Guild was established, followed by the Glasgow and West of Scotland Association for Women’s Suffrage (GWSAWS) in 1902. Together, these and other organisations pushed for greater protections for women throughout society.

After 16 years of struggle, in 1918, women in Scotland and the rest of the United Kingdom were finally granted the right to vote. These pioneering organisations and the women who founded them played a key role in changing perceptions of women. From the reclusive, demonised worker to the strong, independent force, with full and equal rights.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about Victorian era women:

Articles you may also like:

General History Quiz 38

The History Guild Weekly History Quiz.See how your history knowledge stacks up. If you would like an invite to future history quizzes please enter your details below. Subscribe * indicates required Email Address * First Name Last Name History Guild Weekly History Quiz Weekly New History Articles and News Monthly History Guild Update Please leave […]

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.