Reading time: 5 minutes

The Peace of Westphalia, sometimes known as the treaty of Westphalia, is the collective name for three important treaties signed in 1648 that would shape the destiny of Europe. One ended the Dutch Revolt, creating a powerful, independent Dutch Republic, while the other two ended the Thirty Years’ War and gave a measure of peace to Germany and surrounding countries.

By Fergus O’Sullivan

The Peace of Westphalia was more than a handful of treaties, though. According to many scholars, the Peace is where we first see the idea of an international community emerging, with many countries working toward a common goal.

Moving Parts

To understand that a little better, let’s go over some of the events. The three treaties that make up the Peace of Westphalia are the Peace of Münster, the Treaty of Münster and the Treaty of Osnabrück, all of which were signed over the course of 1648. The two cities were then and are now important towns within the area of Germany called Westphalia.

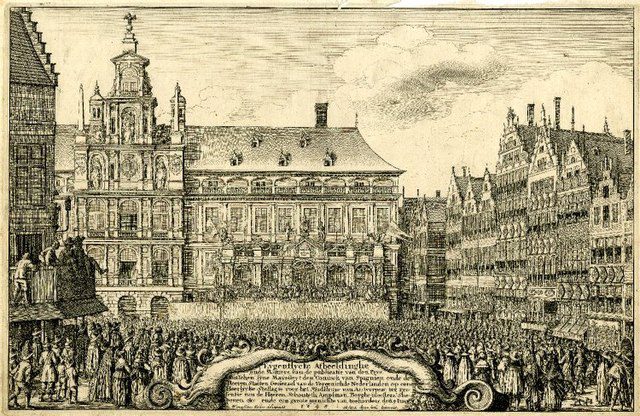

The Peace of Münster ended the Eighty Years War, the independence struggle of the Netherlands against Spain. The Treaty of Münster and the Treaty of Osnabrück were the final act of the Thirty Years War, a brutal war fought in Germany between, well, almost everybody.

When a conflict runs as long as either of these two did, it almost automatically starts sucking in surrounding nations, or even countries far away. The Dutch Revolt, for example, was the catalyst for what would become the massive Dutch overseas empire and saw fighting all over what’s now the Netherlands and Belgium, but also in the New World and Asia. It wasn’t just the Dutch and Spanish fighting, either; the English were involved for a while, as were some German princelings and even French troops.

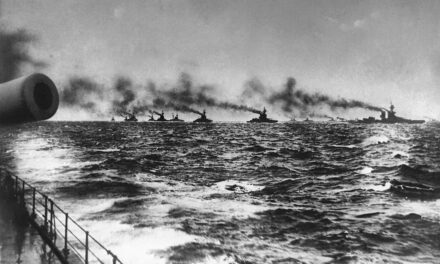

Of course, this pales in comparison to the Thirty Years War in which pretty much all of Europe got involved. Though the bulk of the fighting was contained to Germany and Czechia (the Battle of White Mountain just outside Prague was the first major engagement of the war), the list of belligerents reads like a who’s who of early modern European countries.

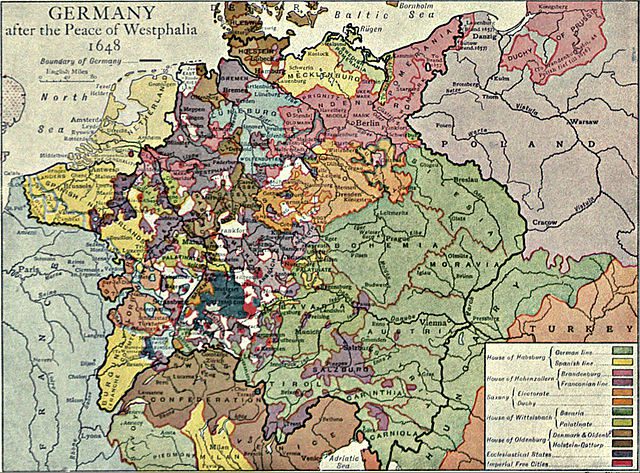

A simplified list includes practically all German states — about 200 or so of them, though fewer after the war — as well as Austria, Hungary, Sweden, Denmark, England, France and Spain, which included Portugal at the time. There were also some related sideshows, like the wars between Sweden and Poland or the Austrian border wars with the Ottoman Empire. The only country not involved in the Thirty Years War was the Dutch Republic, which resisted joining the fray and kept its own war separate from the goings-on in Germany, at least mostly.

All of these countries got involved so they could carve out a little for themselves: Sweden wanted to kickstart its empire, Spain to protect its approach to the Netherlands and Austria to keep control over the Holy Roman Empire.

Getting Together

Because everybody at some point had had a dog in the fight, this means that everybody had an interest in getting something out of it. As a result, when it was time to settle a peace deal, everybody who was anybody descended on Westphalia. In total, 109 delegations attended the negotiations, though not all at the same time.

To get an idea, currently the United Nations has 193 sovereign states as members. Getting anything done requires a massive effort even with modern methods of travel and communication. Imagine hammering out a peace deal in early modern Europe with just over half that number.

Somehow, though, deals were struck in a triumph of international cooperation. However, much as with the Treaty of Vienna after the Napoleonic Wars or the Treaty of Versailles after the First World War, it was the big boys that came out best and the minnows were forced to some extent to be satisfied with the scraps.

Peaceful Cooperation?

Though it may not have been an entirely fair deal for everybody, the Peace of Westphalia did an impressive job of bringing people together and settling some kind of peace on the European continent, or at least in the central part of it. Spain and France would keep fighting for a while longer, for example, and the Ottomans weren’t going anywhere.

Some measure of peace was restored between Protestants and Catholics, though, and the Dutch Republic and the Swiss Confederacy were recognized as separate countries with borders that more or less remain to this day. Germany’s cornucopia of states was brought back to just a few dozen, though a few once independent statelets and cities were doled out to France and Sweden.

Though it may not stand as a triumph of the underdog, the Peace of Westphalia did an amazing job of bringing a lot of people together and ending two massive wars that had cost millions of lives and had devastated the German states. Though it may not have set the standard for international cooperation, it may have laid the groundwork for what was to come.

Articles you may also like

How the National Guard became the go-to military force for riots and civil disturbances

The Pentagon has approved leaving 5,000 troops deployed indefinitely to protect the U.S. Capitol from domestic extremist threats, down from about 26,000 deployed after the Jan. 6 insurrection. The National Guard is a federally funded reserve force of the U.S. Army or Air Force based in states. These part-time citizen soldiers typically hold civilian jobs but can be activated […]

How the shadow of slavery still hangs over global finance

When the infamous Zong trial began in 1783, it laid bare the toxic relationship between finance and slavery. It was an unusual and distressing insurance claim – concerning a massacre of 133 captives, thrown overboard the Zong slave ship. By Philip Roscoe, University of St Andrews. The slave trade pioneered a new kind of finance, secured on […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.