Reading time: 11 minutes

From the moment it took power, the Nazis ruled over a German state possessed of two armies. One was the inheritor of the imperial lineage of the First World War, and the second was the Waffen-SS, which grew from a tiny band of Hitler’s most hardened antisemites to a force of nearly a million men from over two dozen nations before its demise.

By Morgan WR Dunn

Practically no country in Europe went unrepresented in its ranks. And while many of these numbered in the thousands, one people who weren’t left out also made perhaps the strangest and most pathetic contribution of all. They were the British Free Corps, a tiny motley unit of rejects, opportunists, and the occasional genuine fascist who chose to throw their lot in with the Third Reich.

A TREASONOUS PLAN

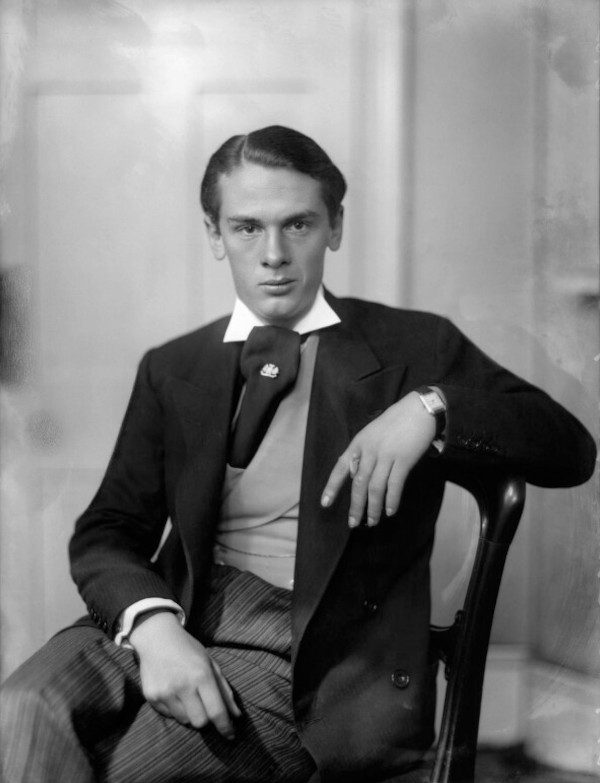

The seeds of what was to become the British Free Corps were sown from the fertile fascist mind of one John Amery. The rebellious son of a prominent British Conservative politician who would eventually serve in Winston Churchill’s wartime cabinet, John washed up in Paris, bankrupt, in 1936 following a string of petty crimes.

Amery made a special project of fascism for the next few years, until he was taken by surprise when the Germans invaded. But a greater surprise came in June 1941, when the USSR allied with Britain:

“It came as a very great shock to me,” he later said, “when I heard that England and Soviet Russia had become allies.” The Soviet Union, in his mind, was the mainstay of a Jewish conspiracy to rule the world, which had incidentally, he believed, been responsible for his financial failures.

Several attempts to escape France failed, and few in Europe seemed interested in his ideas. But in the summer of 1942, an English fascist stuck in occupied territory was interesting enough to Dr. Fritz Hesse, chairman of the England Committee, to merit an invitation to Berlin.

When he arrived in October of that year, Amery presented two ideas. The first was that he be allowed to broadcast an hour-long propaganda radio program. The second, inspired by his friend, the French fascist Jacques Doriot, was that the Germans should establish a unit of British volunteers to fight on the Eastern Front.

Adolf Hitler was immediately enthusiastic about the “Legion of St. George.” The overwhelming propaganda value of a British unit in German service would, Nazi leaders thought, far outweigh its usefulness as a combat formation, and at the end of 1942 plans began to take shape to make the unit a reality. From Hitler’s “Wolf’s Lair” headquarters in occupied Poland came the message:

“The Führer is in agreement with the establishment of an English legion … former members of the English Fascist Party or those with similar ideology – therefore quality, not quantity.”

THE FIRST VOLUNTEERS

It was quantity which would prove the biggest challenge for Amery’s Legion. Amery himself only succeeded in recruiting four men, only one of whom would remain with the unit. At this failure, Amery was reassigned and responsibility for recruitment handed over to an organization eager for soldiers by any means: the Waffen-SS.

Gottlob Berger, the ruthless recruiting mastermind of the SS, and the German Foreign Office agreed that POW camps were their best potential source of British volunteers. Contrary to pop culture depictions, life as a prisoner of war in German hands was anything but happy, marked by pervasive control and surveillance and rigorous hard labor.

Faced with these conditions, the Germans reasoned, British POWs would jump at the chance for a respite, and to that end they founded two “holiday” camps near Berlin. Prisoners could come to the camps to relax, during which the Germans hoped they’d become receptive to the idea of treason.

The plan went awry from the start. Battery Quartermaster Sergeant John Brown, a veteran of the British Union of Fascists chosen to oversee the main camp, began spying on his captors and disrupting recruitment. Thomas Haller Cooper, one of the few British citizens to serve as fully-fledged members of the SS, did everything he could to get away from the unit.

Still, the holiday camps did attract a few recruits. By the summer of 1944, remembered SS-Schütze Eric Pleasants, “the British Free Corps was little more than a year old, by which time the puny bastard organisation” numbered 23. All they needed before they could go to the front, the SS decided, was seven more men – enough to bring it up to platoon strength.

OUR FLAG IS GOING FORWARD TOO

“Broadly speaking,” Pleasants wrote years later, “members of the Corps fell into three categories. First, the ardent National Socialists, indoctrinated with Nazi zeal and, no doubt, some self-interest; then, those who joined to get out of prison camps; and finally, the opportunists, individuals prepared to use any vehicle to get where they wanted.”

The committed fascists were known to the other recruits as the Big Six: British-German Waffen-SS man Thomas Haller Cooper, New Zealander Roy Courlander, Canadian Edwin Barnard Martin, and Englishmen Frank McLardy, Alfred Minchin and John Wilson.

These men developed a uniform, hammered out objectives, dispensed with the name “Legion of St. George” in favor of the shorter and more German-sounding “British Free Corps,” and would become its most notorious members.

At every turn, however, the BFC would fail to meet German standards. Strangely for a unit held to embody the sickening concept of an armed racial elite, the Waffen-SS would eventually draw over half its strength from a variety of nationalities. Units of men from every imaginable European (and many non-European) nationality made up the fighting strength of the SS by 1945.

But those were men from more troubled and chaotic parts of the world and the war. Aside from a brief failed experiment with blackmailing captives into joining, the BFC would struggle throughout its existence with attracting recruits, particularly after the tide turned against the Nazis and not even dedicated fascists could see any reason to throw in with the losing side.

THE BFC GOES TO WAR

54 men passed through the ranks of the BFC, but never enough at once to make it suitable for combat. It didn’t help that even the Big Six were changeable and not altogether trusted. In November 1944, for example, Cooper was convicted of “various heinous anti-Nazi crimes” – that is, planning to request a transfer to a POW camp to escape the encroaching German collapse – and dismissed.

Sensitive to the risks that boredom posed, the SS finally authorized the unit, now just 16 strong, to begin training as combat engineers in Dresden. By January 1945, they’d reached their peak strength of 27, but after Dresden was firebombed and the unit ordered back to Berlin, members deserted, transferred back to prison, or otherwise found ways to escape.

By then, German leaders had accepted that the British Free Corps was an abject failure. But its members still wore German uniforms, and every soldier was precious as the collapsing regime desperately tried to stave off defeat. On March 15, it was ordered, the BFC would go to war at last as a component of the III (Germanic) SS Panzer Corps.

The men of the BFC spent the next month avoiding combat – and certain death – against the Soviets and trying to find enough to eat. They stripped the SS insignia from their uniforms and bounced from position to position as the German military machine crumbled into chaos.

It was then that Thomas Cooper, after spending six months as a military policeman, was reassigned to the Corps and managed to convince German commander Felix Steiner to withdraw the BFC from the front line.

One final danger awaited the men of the BFC. On 19 April, 1945, with the Red Army thundering into Berlin from the east, Cooper returned from a supply-gathering mission to find the Corps being addressed by a blond, aristocratic Englishman who called himself Hauptsturmführer Douglas Berneville-Claye.

Berneville-Claye was a seasoned fraud and liar who’d carved himself a niche as a prison camp informer for the Germans. How he came to join the SS is unknown, but that day he told the men of the BFC that Britain would soon be at war with the Soviets and that he was going to lead them into battle.

The reaction he got was probably unexpected. “You’ve come to drop them back in the shit after I just got them out of it!” shouted an outraged Cooper. It may have been the only time the men were united, but in that moment they backed Cooper. Many had rejoined from POW camps in order to survive, not to die, and Berneville-Claye disappeared.

THE RECKONING

Cooper’s outburst was the high-water mark of the BFC. On April 29, the day before Hitler killed himself, Steiner ordered his forces to flee west in hopes of surrendering to British and American forces. From there, the British Free Corps splintered as individual members felt their own way to the war’s end.

The British Free Corps, from start to finish, had been a miserable failure, and the Germans never seemed to grasp why.

The explanation offered by SS-Untersturmführer Railton Freeman, who finished the war as a member of the SS-Standarte Kurt Eggers propaganda regiment, was that the “camp stool-pigeons and poor types that formed a nucleus that prevented any decent soldiers from associating with them.”

It’s also likely that the idea was realized too late to capitalize on British morale at its low point, and that the deceptiveness and unreliability of the Germans made potential recruits hesitate. Furthermore, the efforts of men like Thomas Freeman, who joined the BFC explicitly to disrupt it and was completely exonerated after the war, and John Brown meant the unit was unstable from the beginning.

In part because no one nation could lay claim to all its members, and because in the chaos of the Nazi regime’s downfall their treason wasn’t always known, the justice the men of the British Free Corps received was inconsistent. Cooper was sentenced to hang, but had his sentence commuted to life imprisonment and died in obscurity.

Others would receive light sentences of just a few months’ jail time, or no penalties at all. Berneville-Claye, for instance, was court-martialled several times and finally imprisoned, briefly, for stealing Army property.

Railton Freeman would receive ten years’ imprisonment. (“This just shows how rotten this democratic country is,” he retorted. “The Germans would have had the honesty to shoot me.”)

Eric Pleasants was unlucky enough to be captured by the Soviets and would spend almost eight years in a gulag. He was spared further punishment when he was finally repatriated in 1954, “but only because he was thought to have suffered enough.”

Not all of them would get away, however. On 25 April 1945, John Amery was captured while wearing a fascist uniform by Italian partisans. Returned to the United Kingdom, he pled guilty to eight counts of treason at his trial and was, as “a self-confessed traitor to … King and country,” hanged on 19 December 1945.

Podcasts about the British Free Corps

Articles you may also like

History’s Greatest Nicknames

Reading time: 7 minutes

A browse through any military history book will no doubt bring up titles of famous officers, often bearing unusual, surprising, or sometimes downright hilarious nicknames. In many cases, it’s clear where the sobriquet originated, while other examples hold a less-obvious significance.

The Long Tail of the First World War

Fallen Empires and Civil War By Caitlan Hester The popular view of the First World War is that it ended with Armistice in 1918. But the end the First World War did not put an end to conflict and combat. The 1918 Armistice was followed by events that radically shaped today’s geo-political landscape: the spread […]

General History Quiz 186

1. When did the Spanish Inquisition begin?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.