LOSING THE WAR IN AN AFTERNOON: JUTLAND 1916

Reading time: 15 minutes

1916 was the pivotal year in the First World War. In February German forces attacked the French at Verdun, while 1 July will mark the anniversary of the Anglo-French offensive on the Somme.

But between these momentous events there occurred the greatest naval battle of the war, and on some measures the greatest in history. On the afternoon of 31 May 1916, the full battle fleets of Britain and Germany clashed for the first and only time, in the North Sea off Denmark’s Jutland peninsula.

Jutland doesn’t loom large in Australia’s memory, because no Australian ships and few Australian seamen took part. But it’s a centenary we should be marking alongside those of more famous battles, because it ensured that Britain would remain the world’s dominant naval power, and that was Australia’s primary strategic objective in the whole war.

Imperial loyalty aside, Australians went to war in 1914 for hard-headed strategic reasons. They depended on Britain’s navy for security from the rising power of Japan, and that would have been lost had the allies been defeated by Germany. That’s what the AIF fought on the Western Front to help prevent, but avoiding defeat on land would have been futile had Germany succeeded in destroying British power at sea.

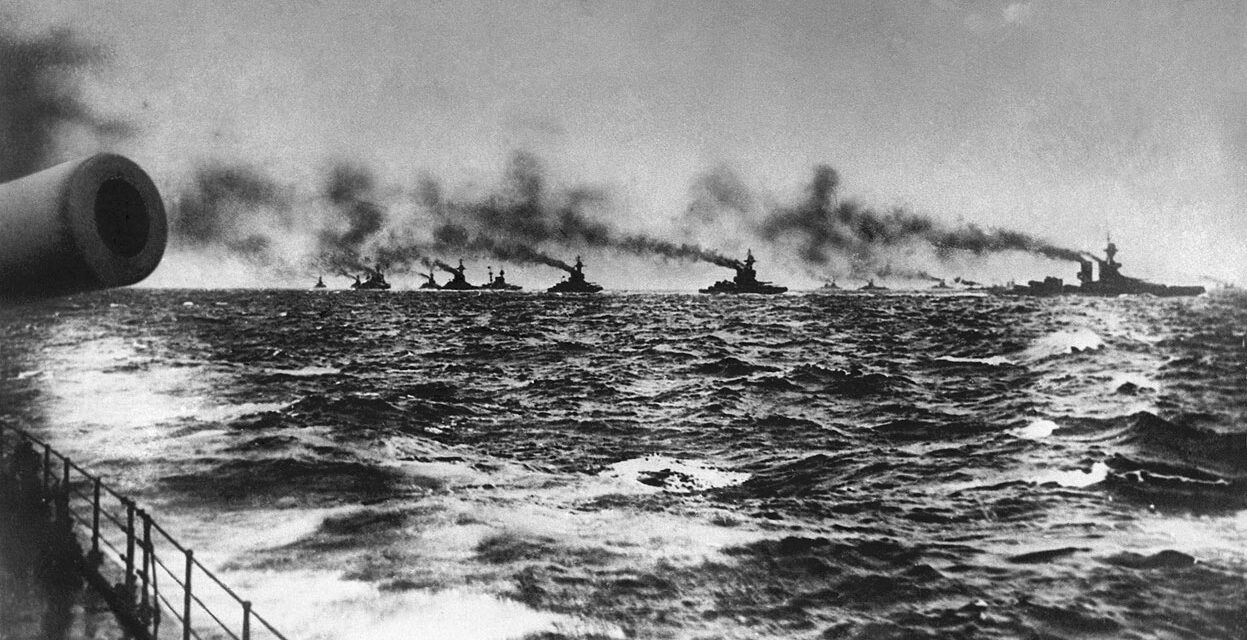

That power was embodied in the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet, based in Scotland. Its 28 battleships and 9 battlecruisers weren’t just the ultimate guarantor of Australia’s security. Simply by being there, they precluded any direct attack on Britain, and strangled Germany’s war effort by blockading its North Sea and Baltic ports.

Preserving the Grand Fleet intact was therefore essential to allied hopes of victory in Europe, as well as to Australia’s security from Japan. Conversely, by 1916 as a decisive breakthrough on land seemed more and more remote, Germany’s hopes of winning the war came to rest on the chance that it could impose a crushing defeat on the Grand Fleet. So Germany needed to fight and win a great naval battle.

Britain on the other hand didn’t need to win a battle: strategically it just needed to keep the Grand Fleet intact by avoiding defeat. That was what Churchill meant when he reflected after the war that the Grand Fleet’s commander, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, was ‘the only man on either side who could lose the war in an afternoon’. He had worried that a full-scale clash might produce the kind of catastrophic defeat that Japan had inflicted on Russia’s navy a decades earlier at Tsushima.

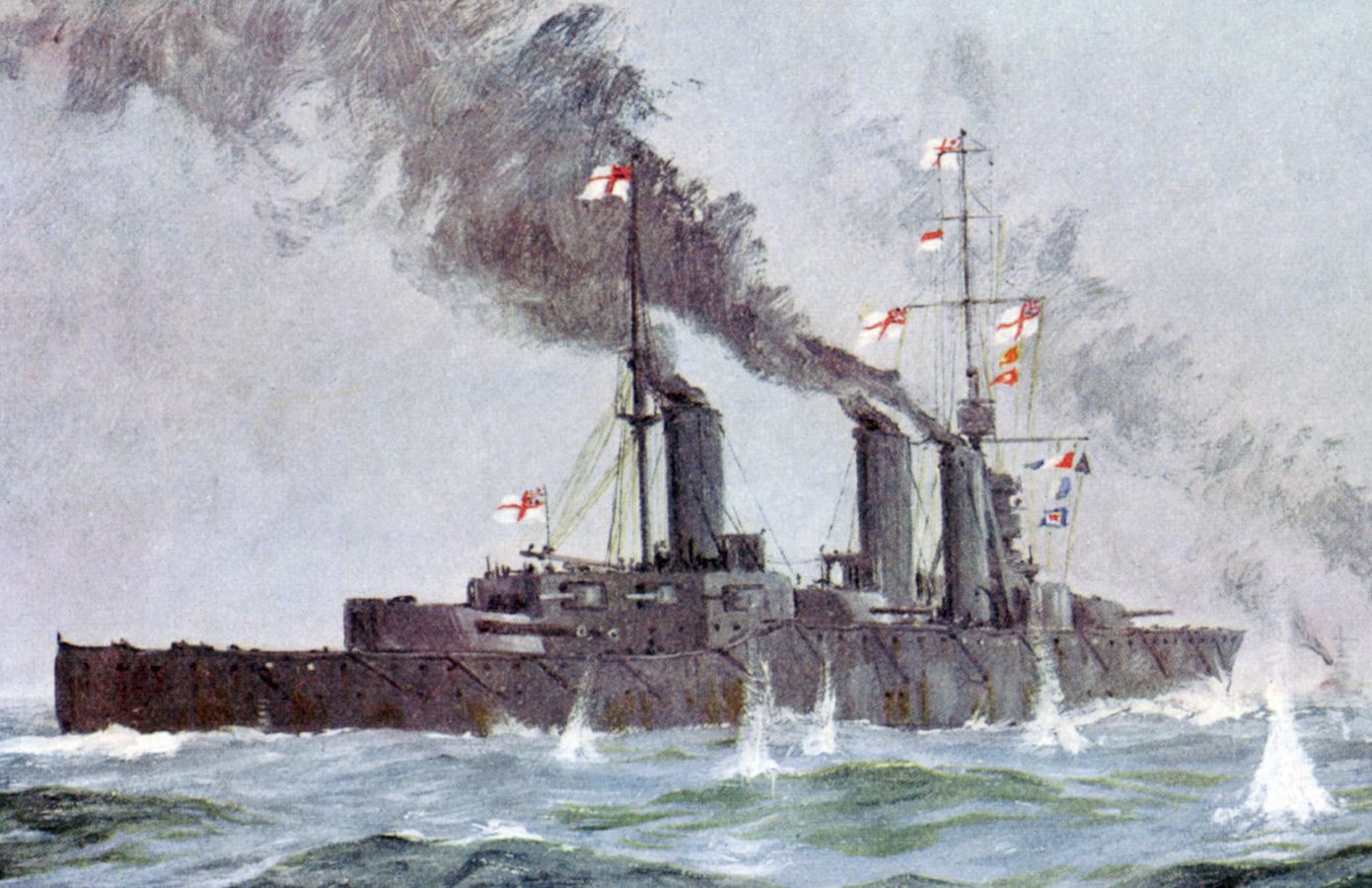

But avoiding battle wasn’t the Royal Navy’s way. Their fighting traditions drove them to seek a crushing victory like Trafalgar, if only to show they were Nelson’s worthy successors. And they had reason for confidence. The Grand Fleet handily outnumbered the German High Seas Fleet’s 16 modern battleships and 5 battlecruisers.

That meant that the German commander, Admiral Scheer, had to avoid facing the entire Grand Fleet at once. His only hope was to meet and defeat a portion of the British fleet with his entire force, after which he could face the remaining British ships with better odds.

That’s what Scheer tried to do on 31 May 1916. He sent his fast battlecruisers into the North Sea, hoping to lure Britain’s battlecruisers out to fight and then ambush them with his battleships. But Jellicoe learned of Scheer’s plan and sent the entire Grand Fleet to counter-ambush Schreer. The stage seemed set for an historic victory.

Had fate not intervened, Australian forces might have played a key role in what followed. The RAN’s flagship, HMAS Australia, was a fast and heavily-gunned battlecruiser serving with the British battlecruisers which were sent to lure the Germans into Jellicoe’s trap. It would have been with them in the thick of the battle, but it was in dock for repairs after ignominiously colliding with HMS New Zealand in fog a few weeks before.

Alas for the Royal Navy, the battle that HMAS Australia missed was no crushing victory. Jellicoe’s trap was sprung on Scheer’s outnumbered and outgunned force, and the great ships with their immense guns blazed away in the late afternoon. But muddle on the British side and swift action by Scheer allowed the Germans to slip away when night fell and head for home.

In fact Germany claimed a victory, boasting that Britain had lost more and bigger ships, and twice as many men. But the Germans lost their nerve, and never again tried to challenge the Grand Fleet. That means that strategically the battle was a British success, because Jellicoe had preserved the Grand Fleet, and neutralised the German naval threat.

But that was little consolation for the failure to win the kind of Nelsonian triumph which, for a few hours that afternoon, seemed so tantalisingly to be within reach. Naval historians still debate passionately about who among the commanders that day was most responsible for the failure, but in fact the outcome had more to do with technologies than personalities.

In the decades before Jutland, naval warfare had been transformed by a whole series of astonishing technological revolutions: from wood to steel ships, wind power to oil-fired turbines, from bronze muzzle-loading guns to 15 inch behemoths, and such utterly new inventions as submarines, torpedoes, radio and aircraft.

Immense sums had been spent perfecting the mighty ships that embodied these new technologies, but they had hardly ever been used in action. No one that afternoon had learned how to fight with them, and in fact no one ever did. The big battleship fleets never met again before the armistice in 1918. Battleships were obsolete by the time the next big naval battles were fought in the Pacific 25 years later. And by then it was clear that Australia could no longer rely on the Royal Navy.

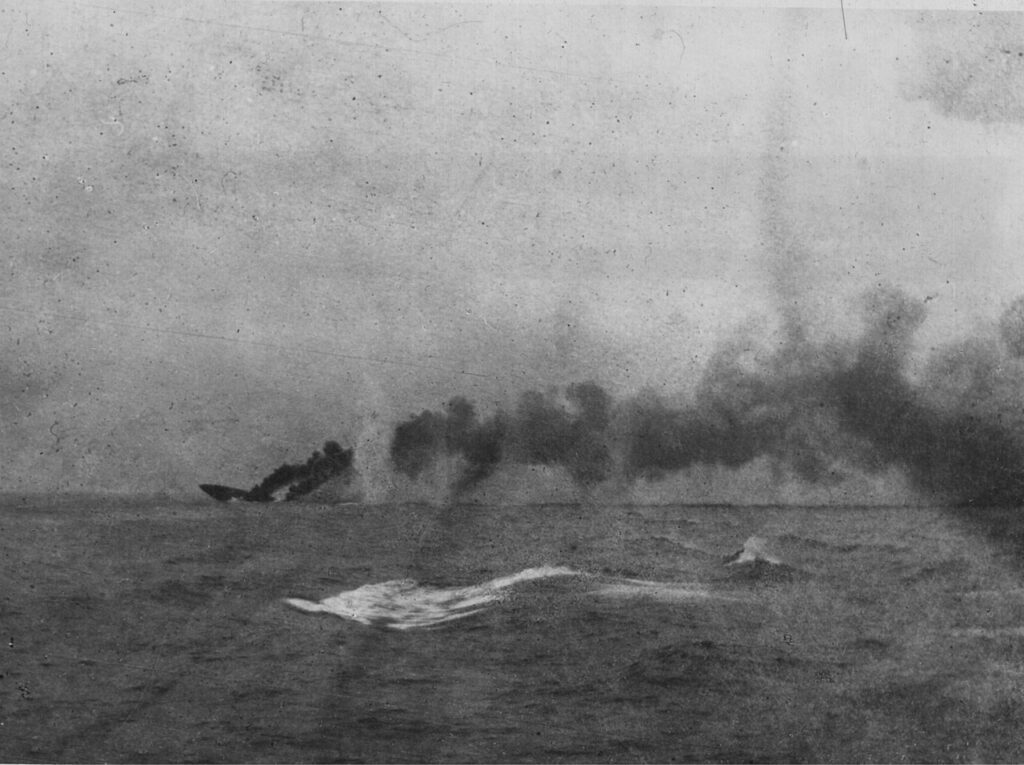

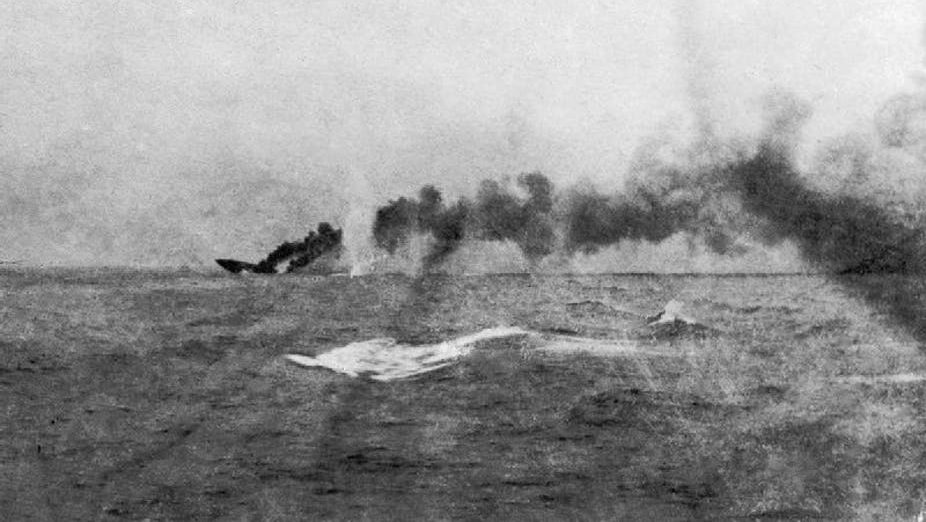

One hundred years ago on 31 May and 1 June 1916, 250 ships of the British and German navies fought an abortive action in the North Sea off the coast of Denmark—the only direct encounter of the two battle fleets during the entire First World War. It resulted in the catastrophic sinking of three British battle cruisers, and uncertainty and confusion amongst the commanders and individual formations and units on both sides. Jutland cost the lives of 8,645 men serving with Royal Navy and the German High Sea Fleet.

The beginning of the battle saw the British Grand Fleet succeed in interposing itself between the German High Sea Fleet and its bases, but later lost that position, unknowingly, as the Germans broke through the light forces in the rear of the British formations overnight. A series of ferocious encounters ensued, but the German movement through the rear was never reported to the British commander, Admiral John Jellicoe. When 1 June dawned, the Grand Fleet was left with an empty horizon as the Germans withdrew. Three British battle cruisers and 11 other ships had been sunk, while the Germans’ smaller High Sea Fleet had lost only a battle cruiser, an old pre-dreadnought battleship and nine other vessels.

Britain and the Royal Navy mourned Jutland. The legacy of the battle was ‘never again’. There was regret for tactical and material failures and the catastrophic losses they caused, regret for the deficiencies of reporting and communications and, above all, regret for the absence of initiative on the part of so many who should have known better.

That collective attitude mattered, for what’s notable about Jutland was the presence at the battle of the Royal Navy’s future leadership. Only one First Sea Lord between 1916 and 1943 was not at Jutland. This continued beyond the Second World War. The commander of the Commonwealth naval forces off Korea in 1950–51 had been a midshipman at Jutland. The First Sea Lord from 1951 to 1955 was at Jutland as a Lieutenant in the Malaya. The statistics for the other naval members of the Board of Admiralty are almost as telling. Gunnery officer Guy Royle on the battleship Marlborough—who would later serve as Fifth Sea Lord and then head the Royal Australian Navy between 1941 and 1945—always felt that he should have engaged the target that he saw at night from the gun control position of the Marlborough without seeking permission from his captain. The latter assumed that the ship looming up in the darkness was friendly—but it was a damaged German battle cruiser, which soon disappeared in the gloom.

In later years, there may have been ‘too much Jutland’. Yet it’s clear that the Royal Navy between 1916 and 1939 functioned in relation to the battle as a ‘learning organisation’. The immediate response to the Grand Fleet’s material problems was remarkable, and a tribute to at least one facet of Jellicoe’s leadership. However, to suggest that command and control moved to a looser regime, particularly after Admiral David Beatty, formerly in charge of the battle cruisers, took over as C-in-C in November 1916 over-simplifies what happened. Many problems remained and had to be endured.

Jutland confirmed that the battle fleet (at some 30 battleships) was too big. Given the forces available on either side, however, the North Sea battle fleets would always be larger than tactically desirable. There was a new emphasis on squadron and divisional tactics and a greater understanding that subordinate flag officers needed the authority to respond individually to an emerging situation. But it’s notable that the drive within squadrons and divisions was to an even greater degree of coordinated manoeuvre, not less. The reason was that concentration of fire became a focus of gunnery innovation, first with two ships and then up to four as a single gunnery ‘unit’.

Night fighting was the subject of new attention, with the realisation that the uncertainty of combat in the darkness could only be mitigated by the development and practice of procedures and tactics understood by all, and initiated automatically, without waiting on direction from the formation commander. Before Jutland, the Grand Fleet’s reactive attitude to action in the dark—and the doctrine and training which resulted—had been based on the assessment that a night encounter with no warning in the open sea was impossible. There was good reason for that given the difficulty of ships finding each other at night. However, any North Sea fleet encounter that started after noon would inevitably continue into a night action, particularly when it wasn’t high summer. After June 1916, the Grand Fleet understood this.

Control and precision were emphasised in another area—reporting the enemy. By 1918, detailed analysis was being produced in the wake of each major Grand Fleet tactical exercise. That not only set out what had happened, but critiqued formation commanders and individual ships. It also included an annex which listed and assessed every reporting signal—and pointed out when signals should’ve been sent, but weren’t. Keeping one’s head below the transmission parapet was no longer acceptable, particularly in a scouting unit.

However, there was more to it than greater control and precision. The mechanics mattered, but what may have been most important was restoring the spirit of the tactical offensive. There were several causes for its frequent absence at Jutland. The Navy’s culture of obedience to the senior officer present was one, particularly as the full implications of the ‘virtual unreality’ created by the assumption that radio contact equated to such presence hadn’t been worked through. While Jellicoe must bear some of the blame, he himself was bitterly disappointed by the lack of enterprise and disappointment behind his later admonition against the ‘virtual unreality’ of assuming that the admiral knew what each ship commander did: ‘Never think that the C-in-C sees what you see.’

The years that followed the Armistice would be difficult for the Royal Navy, marked as they were by an increasingly onerous ‘peace dividend’, as well an unfortunate controversy over the relative performance of the main British commanders at Jutland. Nevertheless, the seeds of change were already sown.

Jutland veterans were not alone in their experience of failure and feelings of regret after the First World War, nor in their desire to get the Royal Navy back on track. Andrew Cunningham, later to achieve fame as the wartime C-in-C of the Mediterranean Fleet, was present, commanding the destroyer Scorpion, when Rear Admiral Troubridge refused action with the German battle cruiser Goeben in August 1914. That was an episode on which the entire navy looked with shame and which clearly marked Cunningham. An officer who was a captain in 1918 wrote that the Royal Navy had ‘an insufficient insistence on the imperative need of really coming to grips.’ This summed up the attitude of many thoughtful officers.

The retrenchments of the 1920’s were dead hands on any initiative that required financial resources. But there were increasingly well-coordinated efforts to improve, which gained momentum in the following decade. The influence of officers who had direct experience of their seniors’ failures (and, perhaps, their own) was important. The Tactical School was a key innovation. There was a healthy dialogue, including the regular publication of ‘Progress in Tactics’ with the results of exercises and trials. What also helped was a growing realisation that the Royal Navy wouldn’t necessarily enjoy technological superiority over its opponents. That placed a premium on identifying tactics which would minimise British disadvantages.

Another vital element was the selection of officers for the most senior seagoing ranks. The reductions of peace meant the Admiralty one priceless advantage—it could be highly selective. No matter how brilliant the specialist officer, nor how significant their staff or ship service, all were placed under a microscope. The weight given to proven initiative was clearly considerable. The promotions to Vice Admiral on the active list between 1934 and 1936 show what happened. Of 15 officers, nine had been awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) and, of these, three had earned it in submarine command and three in destroyers. Rear Admirals of the same seniority tell a similar story—four submariner and four destroyer DSO’s out of a total of 28 officers, 12 of whom had the award. They would be the senior commanders of 1939–45.

Risk taking in battle tactics was accompanied by a willingness to take risks with ships in exercises, a willingness that may have grown as the battle hardened reformers reached flag rank. The wider attitude being engendered was summed up by Admiral Sir William Fisher’s response to frank admission of fault by Captain Philip Vian (of later Altmarck and Bismarck fame) in a berthing accident: ‘I was told to be more careful in future, but the Commander-in-Chief added a paragraph in the sense that he had liked the manner of the confession.’ Andrew Cunningham wasn’t alone when he asserted, after a collision during manoeuvres, that broken eggs are inevitable in making an omelette.

There were misdirections. Whatever the benefits of games for ship spirit and individual fitness, there were excessive claims about the relationship between sport and fighting instincts—and perhaps too much effort devoted to competitive inter-ship sport, as opposed to encouraging group activity. Safety also sometimes exerted too strong an influence. Night operations by submarines were almost non-existent and restrictions on their interaction with surface forces created tactical unrealities.

Unanimity on the subject of command and control was not complete. There was a fissure over the role of staffs. Much commentary has been devoted to the problem of over-centralisation within staffs and commanders who attempted to do too much themselves. But an equal problem, arguably one that has continually dogged the Royal Navy (and other navies) in the years since the Grand Fleet, was that of over-centralisation into staffs and their misemployment on nugatory work, particularly that of minding the individual business of worked-up ships, rather than thinking creatively about tactics, operations and war.

Despite this, by 1939, the Royal Navy had successfully learnt most of the lessons needed to achieve effective remote coordination of operations at sea and the associated exercise of local initiative. Thus, when three cruisers under Commodore Henry Harwood encountered the pocket battleship Graf Spee off the River Plate in October 1939, the British had set the conditions for the encounter. Harwood had considered and gamed—imaginatively—the problem and knew what to do. Like Waterloo, it was a ‘damned nice thing, the nearest run thing you have ever seen in your life.’ But the Graf Spee suffered critical damage and was driven into harbour, from which she would emerge only to be scuttled. Afterwards, the First Sea Lord, Dudley Pound, wrote to Harwood to declare that he had set the standard for the war to come, a matter which Pound felt was of ‘great importance.’ Pound emphasised not only that Harwood had acted correctly, but that he would have been right to engage the Graf Spee even if his entire force was sunk in the attempt.

An Australian element provides a final example. In the Mediterranean in July 1940, Captain John Collins, the product of service and training in both the RAN and RN, decided on his own initiative to reposition his ship, the light cruiser Sydney, by more than fifty miles, keeping radio silence to maintain surprise. The result was the rescue of a group of embattled British destroyers and the destruction of the Italian light cruiser Bartolomeo Colleoni. The exchange with Cunningham, the C-in-C, after Sydney returned to harbour is significant on both sides. When asked what made him move without orders as he did, Collins jokingly replied ‘Providence guided me, Sir’. To which Cunningham said, ‘Well in future you can continue to take your orders from Providence’.

This post was originally published in The Strategist.

Articles you may also be interested in

Why we should remember the Battle of the Coral Sea

The Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942 has become the touchstone for the Australian-American strategic relationship. The 75th anniversary provides an opportunity to reflect on why this engagement, in which for the first time the opposing fleets did not sight one another, still resonates. By Peter Jones During the six months after the […]

After Jutland: the North Sea operations of 18–19 August 1916

One of the Great War’s abiding myths is that the German High Sea Fleet never emerged again after the Battle of Jutland to face the Grand Fleet until the ignominious internment of its major units in November 1918. In reality, the Germans mounted another operation before the summer of 1916 had ended. As soon as […]

Jutland: Why World War I’s only sea battle was so crucial to Britain’s victory

By Andrew Lambert, King’s College London. Modern understanding of World War I is dominated by the immense human cost of the war on land with its trenches, artillery and machine guns – but the war was won by sea power. In August 1914 Britain, the greatest naval power of the age, controlled the oceans, cutting […]

The text of this article is republished from The Strategist in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.