THE FALL OF SINGAPORE

Reading time: 14 minutes

The Land Campaign

Nothing in history is inevitable but the fall of Singapore Island after the defeat of British forces in Malaya came close to it.

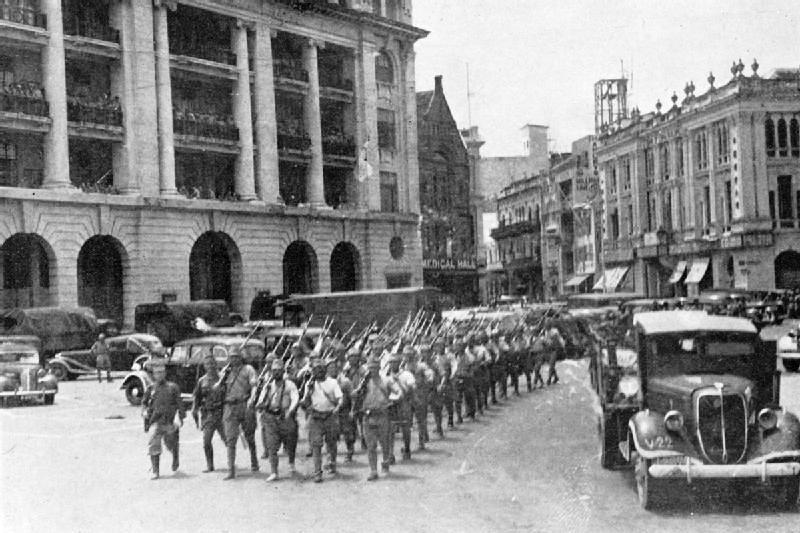

In December 1941 the Japanese established complete air and naval dominance in the region, sinking the British capital ships the Prince of Wales and the Repulse on 8 December and capturing all British air bases in northern Malaya by 20 December. Then, in January 1942, the Japanese armies under the command of Tomoyuki Yamashita advanced down the west and east coasts of the Malayan peninsula, smashing two brigades of the 11th Indian Division at Slim River and overcoming a force of Australian and Indian troops in Johore.

By Joan Beaumont.

With the freedom to launch amphibious landings behind the British troops, the Japanese benefited from personality clashes and rapid changes within the British command, and their poor operational decisions. The Australian Major General Gordon Bennett, for instance, concentrated three-quarters of his forces on the trunk road through Johore, leaving a practically untrained Indian brigade to face the Imperial Guards Division on the important coastal road. The dramatic ambush of the Japanese 5th Division by the Australian 2/30th Battalion at Gemas, though it killed over a thousand Japanese (for fewer than fifty Australian deaths) did nothing to halt the Japanese advance down the Malayan peninsula.

When the British retreated to Singapore Island on 30-31 January 1942, the ‘Singapore strategy’ was in tatters, but could Singapore have held out longer? Perhaps. The Japanese were outnumbered and Yamashita was anxious about their supply position. Most of the naval guns on the island could turn landwards (pace popular mythology). But since they were designed to attack ships not ground targets, their ammunition was primarily armour-piercing not high explosive or fragmentation shells.

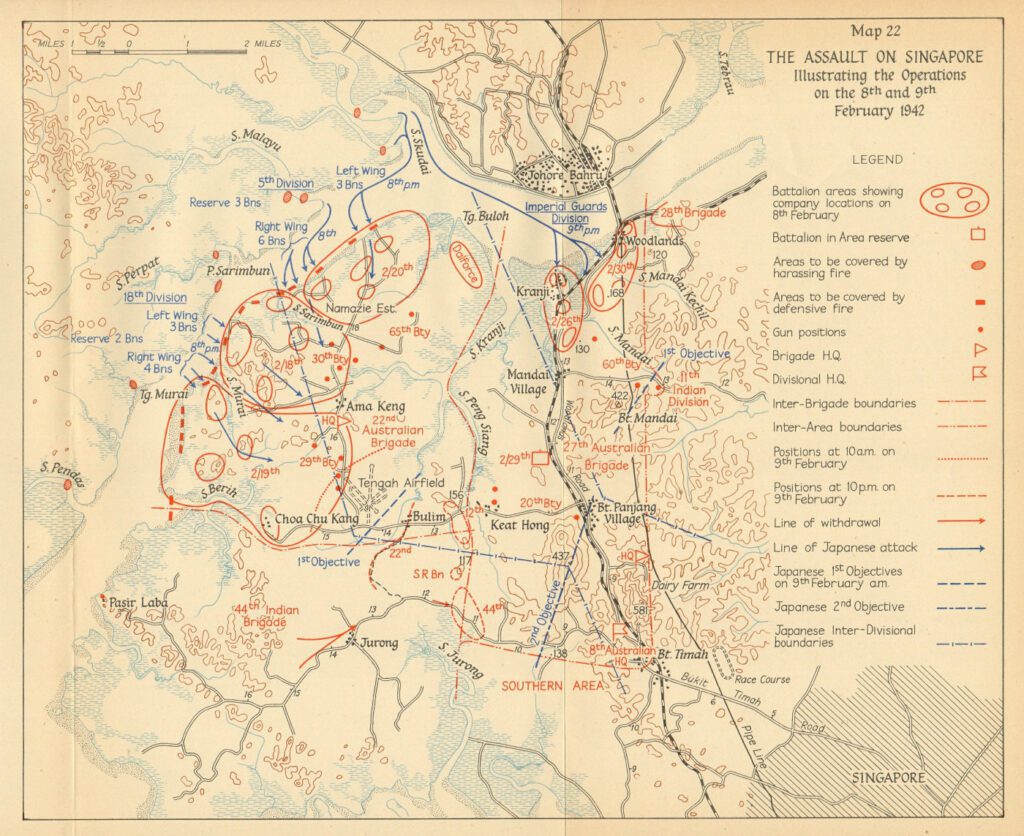

Furthermore, the British commander, Lieutenant General Arthur Percival, who lacked recent experience in operational command, misjudged the Japanese intentions, thinking that they would attack from the northeast. The Japanese instead attacked the north-west of the island, where three half-strength Australian battalions were deployed too far forward and too thinly. Overcoming the Australian resistance, the Japanese drove through the centre of the island towards Singapore Town and Keppel Harbour, but Percival’s deployments did not allow a counterattack. More prudent than willing to take risks, Percival hesitated to commit his reserves from other parts of the islands. Bennett, meanwhile, losing his cool, prematurely issued orders for a withdrawal which meant that the defensive Jurong Line was lost when it might have been held longer. By 15 February, with Singapore’s water supply in enemy hands, ammunition perilously low and civilian casualties mounting, Percival decided to surrender.

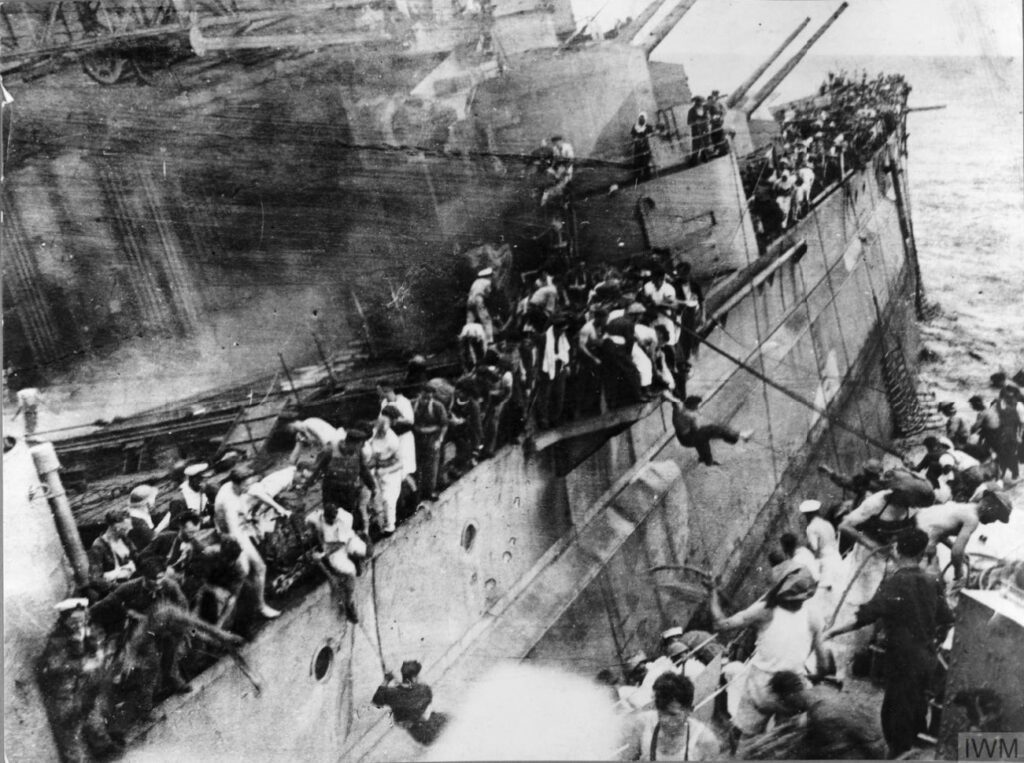

Defeats always lead to bitter recrimination. Bennett blamed the British command, the Indian troops and the British 18th Division. But although Australians are fond of seeing themselves as victims of British incompetence, the performance of Australian troops in Singapore was not faultless. Rather contemporary reports claimed that Australians were guilty of looting, left their lines too early, and crowded the wharves of Singapore in a desperate effort to escape. Sometimes Australians were described as daffodils: beautiful to look at but yellow all through. There were even reports of rapes by Australians in Malaya.

A secret British report documenting this purported indiscipline was released in 1993, and many came to the Anzacs’ defence: the Second Australian Imperial Force’s (Second AIF) 8th Division, it was argued, suffered disproportionately high casualties (10% dead); by February 1942 its units included several thousand barely trained reinforcements; and Australians lacked air cover and were subjected to heavy artillery bombardment in the final battle for Singapore.

However, the sheer number of reports criticising the performance of Australians make them difficult to dismiss. A balanced judgement is that some Australians behaved poorly in the last days at Singapore but they were not alone in this. Moreover, their lack of discipline was a symptom of the British defeat, not its cause.

For all the failures at various levels, it is hard to imagine Singapore surviving a long siege, as did Tobruk, Sebastopol or Leningrad. In early 1942 Singapore Island was simply beyond the reach of Allied logistics. Its survival had always depended on the successful defence of Malaya. This, in turn, was contingent upon the British reinforcing Malaya rather than, as Churchill decided to do in 1940-41, giving priority to the Middle East and aid to Russia (though almost none of aircraft and tanks promised to the Russians were actually sent in 1941).

The Australian Government chose in late January 1942 to warn Churchill that the evacuation of Singapore would be regarded as ‘an inexcusable betrayal’. But Churchill’s relegation of Malaya to a low priority reflected an implacable strategic reality. After the fall of France in June 1940, Britain could not hope to wage war simultaneously against Germany, Italy and Japan. The British Chiefs of Staff had known this since the mid 1930s. Australia’s political and military leaders also should have known this; but they lacked the will to confront this strategic nightmare. Three of the four divisions of the Second AIF raised in 1939-40, after all, were deployed not to Malaya and Singapore but to the Middle East.

With the surrender of Singapore at least 80,000 Allied troops were captured, including nearly 15,000 Australians. Many of them would die in captivity. Among the prisoners was Percival who spent a miserable three years in Formosa (Taiwan) and Manchuria. Bennett, however, chose to escape, purportedly because his expertise in fighting the Japanese was needed in Australia! He never held command in the field again.

A Maritime Perspective

By James Goldrick.

The fall of Singapore reflects failure at many levels, but not in the way most observers think. The British had to fight the war they got in 1939, rather than a war that was yet to happen in 1941. Had the Japanese attacked in the Far East before the Germans attacked Poland, the British would have sent their forces east, however reluctantly. But that wasn’t the order of events.

The greatest naval defeat the British suffered in World War Two wasn’t the destruction of the Prince of Wales and Repulse in the South China Sea in December 1941, but the fall of France in June 1940. By removing the French fleet from the Allied order of battle, bringing Italy into the conflict with its substantial naval strength, thus making the Mediterranean a theatre of war, and opening the French Atlantic ports to German U-Boats and surface raiders, France’s defeat made the load on British global naval strength more than could be borne. Britain’s strategic over-extension finally hit home.

The ‘Main Fleet to Singapore’ policy was a much more credible strategy than hindsight has allowed. Admittedly, there were deficiencies. The British build-up of forces and facilities was too slow, hindered by a combination of financial constraints and well-meant efforts at disarmament. Not enough was done to develop the land and air forces necessary for what would have always been a conflict fought both at sea and on land, notably in Malaya. The Dominions’ support, particularly in fighting forces, never matched the promises made at the 1923 Imperial Defence Conference.

But the British did many things to make the fleet deployment work. The logistic challenges were huge, but Middle East oil had not much further to move than it did for forces in British waters. The Singapore naval base build-up was fitful, but by 1928 a floating dock capable of taking a battleship was on station and a ‘Mobile Naval Base Defence Organisation’ was set up which could create an advanced base in the most isolated anchorages.

The British Navy regarded the Imperial Japanese Navy as its principal threat. Many assessments of Japanese capability were racist, but some were accurate, displaying understanding of the cultural elements involved. The British feared that the Japanese had superiority in several areas, particularly long range gunnery, and knew they had to evolve their own tactics with the assumption that the Royal Navy would be the weaker force.

Thus, at the same time as the Japanese were evolving night fighting techniques, the British were improving theirs. The long range Japanese torpedoes would have come as a surprise, but the British might have done rather well had they met the Japanese at the peak of their own training. The Royal Navy also didn’t underestimate Japanese naval aviation, at least its seaborne side. By 1934 Far East naval commanders were trying to convince their Air Force opposite numbers that they expected Japanese carriers to launch mass air strikes against Singapore from over 100 miles away. What the British didn’t understand, was that the IJN was also developing highly capable land based naval aircraft—such units would destroy Force Z in 1941.

The British knew they had to buy time for the Mediterranean Fleet and troops from India to get into theatre—the ‘period before relief’ (estimated in 1932 as 38 days). They had progressive ideas about this. Until well into 1940, the Royal Navy maintained a strong submarine force in the Far East. In 1939, this included 15 operational units, more than the combined total in the Home and Mediterranean Fleets. These boats practised wolf pack tactics in combination with RAF flying boats for the expected Japanese invasion convoys. In a precursor to the Cold War, they also conducted covert submerged intelligence gathering on the Japanese fleet in its own anchorages. One of Australia’s key failures was in going no further to develop the submarine flotilla it promised than the pair of boats commissioned in1927. So low did Australian defence spending fall that the RAN gave both submarines to the Royal Navy in 1931. There should have been six Australian boats blocking the deep water passages of the Indonesian archipelago, while British submarines operated in the South China Sea and around Japan.

The Abyssinian crisis was the first nail in the coffin for the ‘Main Fleet’ strategy. By 1938, capability developments were hammering in more. Until then, the potentially hostile navies had not the number of modern ships to threaten Britain. German and Italian warship completions rapidly changed the balance. Until then, the Japanese Navy could only field on average three carriers and six battleships. This had been manageable. During 1938, these deployable numbers increased by 50%. They would increase by another 50%—with more powerful ships—by the end of 1941.

The 1938 crises changed the British focus to Europe. After France’s collapse, holding on in the Mediterranean was a gamble based on the Japanese staying out of the war. But, in the circumstances of 1940, were there any options?

That the ‘play’ should have been properly explained to Australia, that Australia should have worked out the consequences for itself—and that Britain and Australia should have done more over two decades for their own defence and for the support of the ‘Main Fleet’ strategy with sea, land and air units must be the real ‘lessons’ of the affair for us.

The Lessons of Alliance Failure

By Hugh White.

Most of us would agree that the Fall of Singapore in February 1942 remains the biggest strategic shock Australia has ever received, but we pay too little attention to why it was such a shock, and what we can learn from it.

The humiliatingly easy defeat of the island’s defences by the Japanese was of course a catastrophic military failure, with grave consequences for those whom it engulfed. But the island and its base had little strategic significance to Australia when there were pitifully few ships and aircraft to operate from it. The real strategic shock was not that Singapore fell, but that it was useless because Britain could not commit forces to operate from it strong enough to have any chance of contesting Japan’s ability to project power around the Western Pacific.

This was a quintessential failure of an alliance, and of a strategic policy based on alliances. It marked a whole generation of Australians and profoundly shaped our strategic thinking for decades. And it carries important lessons for us today.

The seeds of the disaster were planted long before 1942. The British naval power in Asia which had guaranteed Australia’s security since the First Fleet was already falling sharply before the First World War, and fell even further after it. Unable to maintain a major battle fleet in the Pacific, Whitehall planned to meet any threat by sending the main fleet from Britain to the base at Singapore.

But it was always obvious that this would not be possible if Britain faced a simultaneous threat in Europe, and though the 1930s the risk of simultaneous crises with Germany and Japan plainly grew. Nonetheless, Australians persuaded themselves to depend for their defence from Japan on Britain’s ability to send massive air and naval forces to Singapore if and when they were needed.

When the time came, Britain’s air and naval forces were utterly committed to defending Britain itself, and to an intense maritime struggle for control of the Mediterranean on which its entire strategy for holding Germany depended. No one can blame British leaders for giving these commitments priority. They made the right decision for Britain.

The blame lies with Australian leaders for erecting Australia’s strategic policy on such flimsy foundations. In their defence they could cite Whitehall’s frequent assurances that the fleet would be sent if it were needed, but they knew those assurances meant nothing if there was war in Europe. And yet they clung to them as the danger of concurrent wars in Europe and Asia quite plainly grew. This was a massive failure of strategic policy.

At the heart of this failure was an inability to recognise and accept fundamental shifts in the distribution of wealth and power which were transforming both the global and the regional strategic orders, and undercutting Britain’s place in them. Britain with its world-wide commitments simply could not match Japan’s strategic weight in Asia any more.

These shifts had been underway for decades, and had been perfectly well understood by an earlier generation of leaders like Alfred Deakin. But the men of the 1930s lacked the insight and perhaps the courage to see what was happening and what should be done about it. In part no doubt that was because they simply couldn’t imagine what the alternatives might be. What else could Australia have done except rely on the Royal Navy?

It is a question which even now deserves attention. Was there a policy Australia could have adopted that would have lessened our dependence on Britain and allowed us to defend ourselves against Japan? John Curtin thought there might: as Labor leader in the late 1930s he suggested that an independent force of aircraft and submarines might be able to keep Japanese forces from our shores.

He may have been right, but this kind of independent strategic posture would have required not just massive investments but a shift in national outlook and even identity which most Australians could not encompass, and which most leaders were not prepared to consider. Perhaps by the late 1930s it was already too late anyway.

Of course as prime minister in late 1941 Curtin did find another alternative—turning to America, which thankfully worked well for a while. But the experience of alliance failure haunted those who had lived through 1942. The lesson that no ally, no matter how deeply connected by shared values and history, can be relied upon when the crunch comes shaped both the Forward Defence posture of the post-war decades and the Self-Reliance policy which followed.

Only in the last twenty years has that lesson been forgotten. Since about 1996, and especially since the mid-2000s, Australian political leaders on both sides of the aisle have become sublimely confident that Australia’s security can be entrusted to the care of our principal ally. Few now suggest that Australia might need to defend itself and its most vital interests independently.

And this is despite the fact, so obvious but so seldom acknowledged, that that the fundamental distribution of wealth and power has been shifting rapidly against the United States. Today, relative to its Asian rivals, America is weaker economically, diplomatically and militarily than it has been since World War Two, and yet we rely on it more. The parallels with the years before Singapore are all too obvious.

So the Fall of Singapore holds a vital lesson for us: that alliances can and do fail, and that any strategic policy that does not give that reality due weight is likely to fail too. The question, of course, as it was in the 1930s, is: what’s the alternative? That is the question we should be addressing much more seriously. There are answers to be found, but they are not easy ones.

This article was originally published in The Strategist.

Listen to a great podcast series about the campaign

The Principals of War has produced an excellent series that examines the campaign leading up to the fall of Singapore in detail. Listen below.

Articles you may also be interested in

The Coral Sea, 1942: a nation-saving battle

THE CORAL SEA, 1942: A NATION-SAVING BATTLE The Battle of the Coral Sea isn’t as iconic in our national consciousness as Gallipoli, Kokoda, or even El Alamein, Villers-Bretonneux, Amiens or Beersheba. Those battles and others in the two world wars played into our evolving sense of what we were, and are, as a people, and […]

Deng Xiaoping’s Rise to Power

By orchestrating China’s transition to a market economy, Deng Xiaoping has left a lasting legacy on China and the world. After becoming the leader of the Communist Party of China in 1978, following Mao Zedong’s death two years earlier, Deng launched a program of reform that ultimately saw China become the world’s largest economy in terms of […]

Rising Sun, Complacent Bear: The Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War resulted in one of Russia’s greatest military upsets, and one of Japan’s most significant military victories, in modern history. By Madison Moulton At odds over imperial ambitions in Asia, a recently modernized Japan declared war on Russia in 1904, sparking a year-long conflict that set the stage for the century of war […]

The text of this article is republished from The Strategist in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Hi All

I conduct a lot of research regarding aspects of WW2 as demanded by my Philatelic writings, that are widely published in a number of countries. Strangely, this is the first time I have listened to your podcasts in my investigations. I have started listening to the ‘Malayan Campaign’ series and have found it to be an excellent general, but insightful coverage of the topic. The presenter provides an eloquent, contemporary (in a post-colonial sense) and well briefed delivery. Having done much research into this topic using current literature, I still found the content here provided some new insights; a refreshing perspective; and frank and and honest approach to a socially, politically and militarily sensitive subject .

I will continue to use this excellent resource in the future.

Than you,

Best wishes,

Nick