Reading time: 9 minutes

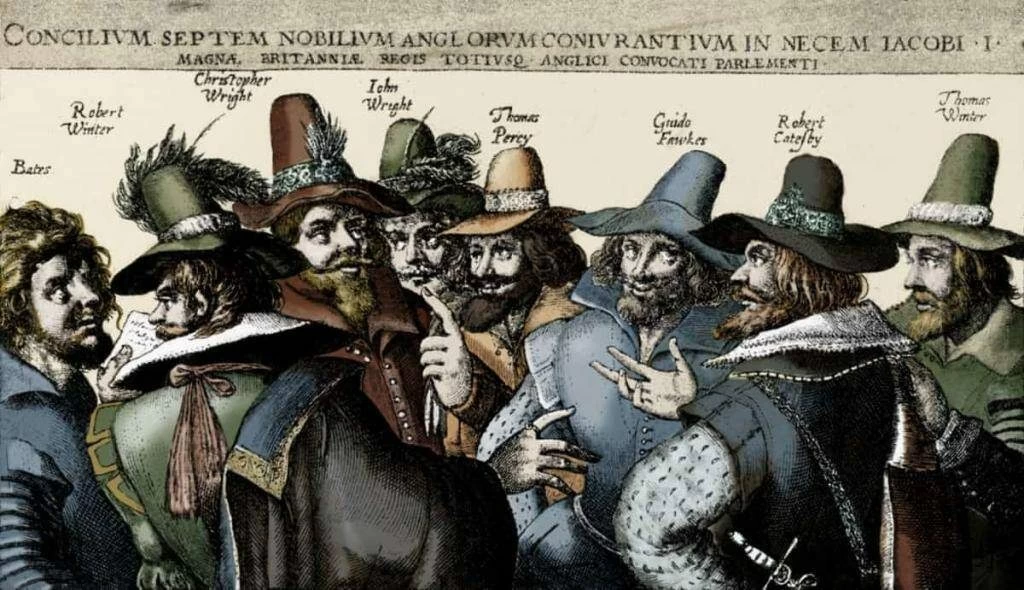

On the night of 4 November 1605, a man calling himself John Johnson was found in the vaults beneath the House of Lords with 36 barrels of gunpowder. Under questioning, Johnson – whose real name was Guy Fawkes – admitted that he and his co-conspirators planned to use the gunpowder to blow up the House during the State Opening of Parliament on 5 November.

If successful, this plot – which became known as the Gunpowder Treason, or Gunpowder Plot – would have killed not only King James I (and VI) but members of his family, his chief ministers, and the Members of Parliament in attendance at the state opening. This was treason on an unprecedented scale – an attempt to destroy both the king and his government.

By Daniel Gosling.

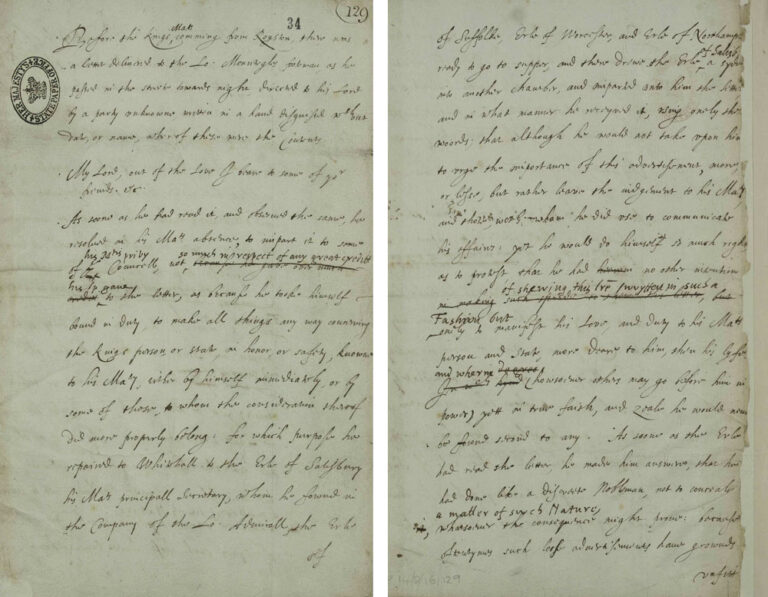

The National Archives holds hundreds of documents detailing the discovery of this plot and the prosecution of those responsible. Included in our State Papers collection is a letter written on 7 November 1605, just days after the discovery, detailing the events which resulted in the capture of Guy Fawkes and the thwarting of the Gunpowder Plot. The letter, written by Levinus Muncke – the secretary of Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury – is transcribed below, providing a unique contemporary account of the discovery of the Gunpowder Treason. Language has been modernised and some passages abridged for ease of reading.

A view from the time

‘Before King James I (and VI) returned from Royston, there was a letter delivered to Lord Monteagle’s footman as he passed in the street, directed to his Lord by an unknown party, written in a disguised hand without date or name, whereof these were the contents:

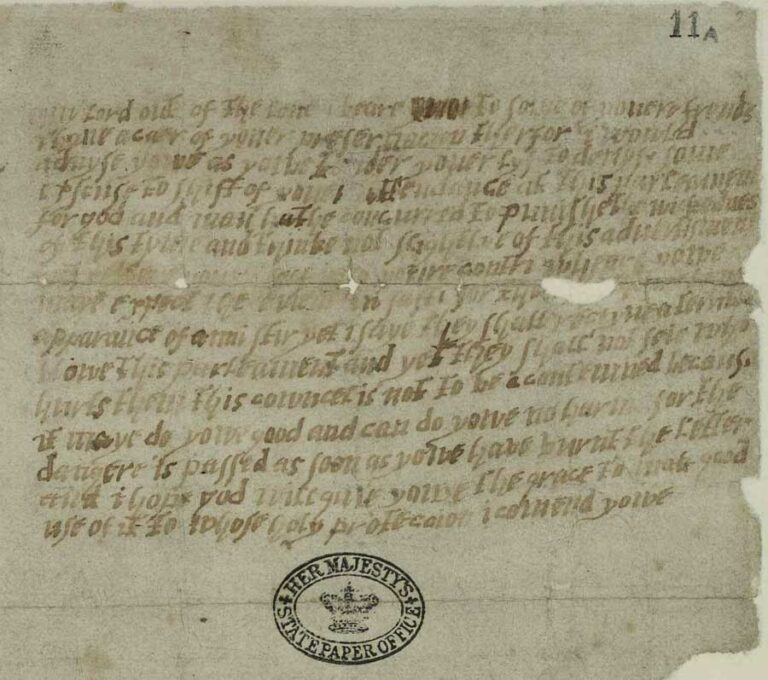

My lord, out of the love I bear to some of your friends, I have a care of your preservation, therefore I would advise you, as you tender your life, to devise some excuse to shift off your attendance at this Parliament, for God and Man have concurred to punish the wickedness of this time, and think not slightly of this advertisement but retire yourself into your country where you may expect the event in safety; for though there be no appearance of any stir, yet I say they shall receive a terrible blow this Parliament, and yet they shall not see who hurts them: this counsel is not to be contemned, because it may do you good and can do you no harm, for the danger is passed as soon as you have burnt the letter, and I hope God will give you the grace to make good use of it, to whose Holy Protection I commend you.

[The Monteagle Letter, SP 14/216/1, fo 11a. On display as part of our exhibition, Treason: People, Power & Plot]

As soon as he had read it he resolved in the King’s absence to impart it to the Privy Council. He repaired to Whitehall to Robert Cecil the Earl of Salisbury, His Majesty’s Principal Secretary, whom he found in the company of Charles Howard the Lord Admiral, Thomas Howard the Earl of Suffolk, Edward Somerset Earl of Worcester, and Henry Howard Earl of Northampton, ready to go to supper, and there drew the Earl of Salisbury aside into another chamber, and imparted unto him the letter and in what manner he received it.

After reading the letter, the Earl of Salisbury asked the Earl of Suffolk to join them, where they three perused the letter again. Observing that the words presaged some desperate practice against the King and the whole state, and that the party was so careful to procure the Lord Monteagle to be absent from the Parliament House, they concluded that there would be some attempt upon the King and all that were in the Parliament House. Whereupon the Earl of Suffolk, who as Lord Chamberlain has the care of all the places where His Majesty visited, remembered that there were rooms adjoining the chamber of Parliament in which he had never been, and therefore it was agreed that he would take some particular care of that point.

After the Lord Monteagle was gone, the Lord Admiral, Earl of Worcester, and Earl of Northampton were all made privy to the letter. They all fell upon the same consideration and resolution, that the Lord Chamberlain should take care to visit all those places, but not before the session, both because they had only received the one warning and also because they did not want to alert any plotters before they could be discovered.

Some three days after, His Majesty returned from Royston (being the 31st of October) to whom the Earl of Salisbury showed this letter privately. When His Majesty had read the letter he made this short reply. As the words seemed to presage danger to the whole court of Parliament, over whom his care was greater than over his own life; and because the words described such a form of doing as could be no otherwise interpreted than by some stratagem of fire and powder, he wished that there might be especial consideration made of the nature of all places yielding commonly for those kinds of attempts; and then, as he should be informed of all particulars, he would deliver his further pleasure and direction how the matter should be carried.

His Majesty further directed that some good observation should be made of all who should without apparent necessity seek liberty to be absent from Parliament; because it was improbable that among all the nobility this warning should only be given to one. And so the matter being left for that time, it was agreed by all that the Lord Chamberlain should take occasion to repair to the Parliament house the day before to see the rooms, according to his accustomed fashion, and so under some other colour survey all places under those chambers.

On 4 November, about 3pm, the Lord Chamberlain accompanied only with the Lord Monteagle (who was very desirous to go thither himself) went accordingly to the Parliament House: and after some time spent above in the place where the King and both Houses should assemble, he took an occasion, by reason of some stuff of the King’s, which lay in part of a cellar under those rooms, in the keeping of one Wynyard (an honest and ancient servant of the late Queen Elizabeth I) to go down into some lower rooms, and thereby finding that Wynyard had let out some part of a room directly under the parliament chamber to one that used it for a cellar, he only looked into it slightly; and observing stores of coal, billets, and faggots piled up, he asked to whom it belonged; whereunto, when answer was made by him that had the key [Guy Fawkes, posing as a servant] that the wood belonged to one Mr Thomas Percy, one of His Majesty’s pensioners, his lordship inquired where he was and how long he had kept house there; to which it was answered that he had taken that house a year and a half since, but had deferred his lying there in respect of some other occasions which had forced him to be absent.

As soon as the Lord Chamberlain heard that, remembering that Percy was a Catholic, and observing the commodity which that place might yield for a devilish practice: he began to apprehend the more necessity still to look into the matter, though no other materials were visible in the place than were ordinary to be bestowed in such rooms; but he did not yet order for the search of the rooms until he had returned to the King. To which it is not amiss to add this circumstance, that the Lord Monteagle had misgivings at hearing Percy’s name, as he very earnestly told the Lord Chamberlain that the more he observed the words of the letter, which contained a friendly warning, the more jealous he was of the matter, and of this place, because there had been indeed long acquaintance and familiarity betwixt Mr Percy and him, and also because he never had so much as any inkling that he lay there.

And so to be short, the Lord Chamberlain returned to the Court to inform His Majesty what he found. This was now betwixt five and six o’clock at night. His Majesty called unto him some other of the Lords that were in the Gallery (where also the Lord Treasurer was present), collected again the circumstances and resolved of a search to be made to the bottom of that vault, declaring that in such a case as this, he ever held one maxim, which was either to do nothing or else to do that which might make all sure.

Accordingly, choice was made of Sir Thomas Knyvet, a gentleman of His Majesty’s privy chamber of great fidelity and good discretion; who suddenly and severely repaired to the place about 11 o’clock, and found the same party who the Lord Chamberlain and Lord Monteagle had previously encountered, departing from the vault. After the diligent and careful removal of all the materials in the vault, he found the whole mass of powder which was laid in for execution of this most tragic and devilish work intended: whereupon the caitiff being surely seized, he made no difficulty to confess that the same should have been executed on the morrow. Whereupon Sir Thomas Knyvet binding him hand and foot, leaving a good guard upon him and upon the place, immediately returned to the Court, to the Earl of Salisbury’s lodging, about one o’clock at night, to whom he imparted the matter. Sir Thomas Knyvet then went to the Lord Chamberlain, and from there sent word to the Lord Admiral and the Earls of Worcester and Northampton, who sent for all the Lords of the Council in the house to repair to the King’s bedchamber, where an order was given to Thomas Erskine Lord Dirleton to make all doors fast, after which they repaired to the King and caused Sir Thomas Knyvet to deliver all he had found.

As soon as His Majesty heard it he rendered a religious thanksgiving to almighty God for His gracious goodness in this discovery, no less in respect of his dear and worthy subjects, who should all have perished with him, than for himself, and so with no manner of alteration resorted straight to direct his Council, how to proceed in all things depending upon such an accident; first, to command the Lord Mayor to set a guard of honest citizens, for prevention of sack or spoil of them, if upon this discovery the parties guilty should seek to stir any tumults; next, to preserve the prisoner from killing himself, with diverse other directions.

Whereof you have seen the happy effects.’

Terrible consequences

The story of what followed is well-known. The ringleader of the plot, Robert Catesby, was killed in a shootout on 8 November 1605 with a number of other plotters. Those surviving conspirators – including Guy Fawkes – were captured and tried for treason in January 1606, suffering the traitors’ deaths of hanging, drawing and quartering.

The Observance of 5th November Act was passed in 1606, making 5 November a day of remembrance and thanksgiving. Though that act was repealed in 1859, we still remember the actions of the plotters, and the discovery of this unprecedented treason, to this day.

This article was originally published in The National Archives.

Podcasts about the Gunpowder Treason:

Articles you may also like:

Broodseinde Ridge – Podcast

On the back of the victories of Menin Road and Polygon Wood, the 1st Anzac Corps pushed on towards the dominating feature of Broodseinde Ridge. This time though, they would have the men of the 2nd Anzac Corps fighting alongside them. The Battle would see the Allied troops looking down upon green pastures for the first time in three years, bringing hope that the war may soon be over.

General History Quiz 50

The History Guild Weekly History Quiz.See how your history knowledge stacks up. Have an idea for a question? Submit it here and we’ll include it in a future quiz! Please leave this field emptyTell me about New Quizzes and Articles Get your weekly fill of History Articles and Quizzes We won’t share your contact details […]

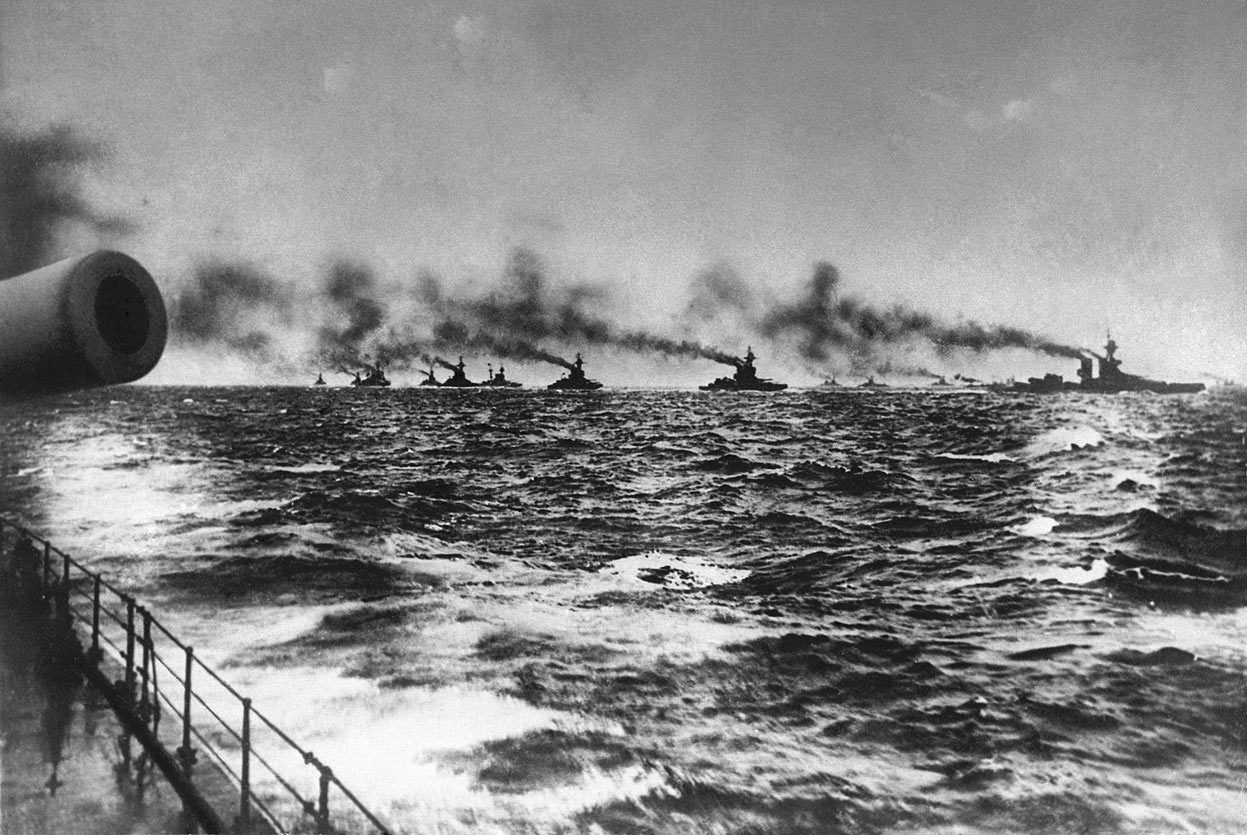

Losing the war in an afternoon: Jutland 1916

1916 was the pivotal year in the First World War. In February German forces attacked the French at Verdun, while 1 July will mark the anniversary of the Anglo-French offensive on the Somme.

This article was first published by The National Archives. It is reproduced in accordance with the Open Government Licence v3.0.