Reading time: 7 minutes

Arriving in occupied Paris in February 1944, Eileen Nearne’s mission was fraught with danger. She was a secret wireless operator providing a vital line of communication between British intelligence and the French resistance. Working undercover, these were the months leading to D-Day.

In extremely risky conditions, she worked with ‘cool efficiency, perseverance, and willingness to undergo any risk in order to carry out her work’. From Paris, she communicated key information including enemy plans and movements. After almost six months behind enemy lines, while transmitting information to London, Eileen was captured by the Gestapo and sent to a German concentration camp. Remarkably, she survived the war.

By James Cronan, The National Archives

On her return to the UK, in 1946 she received an MBE ‘For services to the Allied cause’. Eileen’s is just one of the many names found in 166 files of the Treasury Committee appointed to approve nominations for gallantry awards to civilians in the Second World War.

‘The Darkest Hour’

The story of civilian honours starts in September 1940, when two new awards, the George Cross and the George Medal, were instituted to recognise the outstanding contribution made by civilians during the Battle of Britain and the Blitz. These awards were primarily aimed at those involved in civil defence, such as Air Raid Precautions officers, rescue party workers, fire fighters and casualty and medical service workers. But they also recognised vital work carried out by the police service, gas workers, electricians, train drivers and dockyard workers to keep Britain going in what Winston Churchill described as ‘The Darkest Hour’.

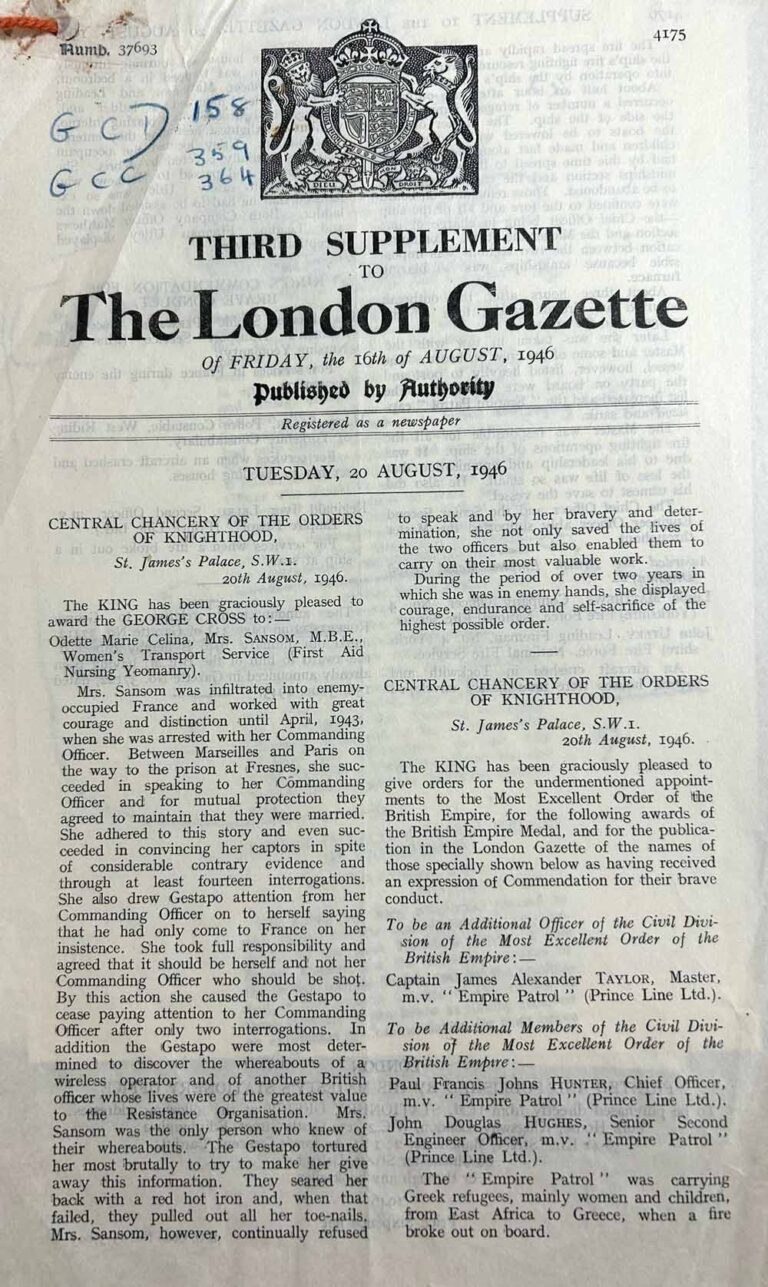

The papers of the Treasury Committee can be found in series T 336. Each file contains a listing of individuals recommended for awards, organised by case number, followed by submission papers from the recommending department with details of the individuals and the action that led to a recommendation. In some cases, there are supporting witness statements. There are also papers of the ceremonial branch giving their deliberations and decisions, and a copy of the announcement award in the supplement of the London, Edinburgh, or Belfast Gazette.

More ways to search

There are 166 files in this record series. Prior to this project the catalogue described each file as ‘Wartime awards in Civil defence’ and listed the date of the announcement in the London Gazette. A search by the name wasn’t possible and the files weren’t consulted very frequently. For each file we have now input the first names or initials and surname of all those awarded or considered for an award, together with age, occupation, award granted and summary of the grounds for recommendation.

In line with the Data Protection Act, the details of occupation and grounds for recommendation have been redacted in cases where the age is not known to us or where the age indicates that the person would still be under 100 years old. These details will be released on to the catalogue when either the age of the individual reaches 100 years old or when the action for which an award was recommended does so.

Roughly 6,500 names have been added to Discovery, the National Archives online catalogue. As well as listing locations of the events we have also listed the associated towns, cities, and counties. This will help people researching bomb damage and explosions during the Second World War. As expected, there is a large amount of recommendations for events which took place in London and in other ports and cities targeted by the Germans, such as Manchester, Liverpool, Cardiff, Swansea, Coventry Hull, Birmingham, Bristol, Southampton and Plymouth.

Off duty awards

The committee also considered awards for military personnel who were off duty and acting in a civilian capacity when they came to the aid of others. There are a significant number of awards for men and women in the Army, Navy, Royal Air Force Home Guard and the Merchant Navy.

A large number of the awards went to women, such as the commendation to Mrs Annette Madeline Lennard, who was in charge of an ARP (Air Raid Precautions) Mobile Canteen Casualty Service in Bristol and provided food and refreshment after – and sometimes during – heavy bombing. Towards the end of the Second World War the files concentrate on gallantry overseas, by civilians caught up in enemy occupied territory. T 336/161 contains submissions recommending civilian OBEs (Orders of the British Empire, national honours) to British war correspondents and T 336/152 consists of recommendations for awards for British officials in the Channel Islands, which were occupied by Germany.

Awards for those overseas

T 336/160 contains details about the awards of OBEs for a civilian internee in Java and two British civilians in Shanghai who were beaten and subjected to water torture by the Japanese. It also contains papers recommending an MBE (Member of the British Empire, another national honour) for Mrs Edel Chalmers, a Norwegian woman married to a British man in the north of Norway. She allowed her house to be used by an SOE (Special Operations Executive, the British intelligence organisation) agent and wireless telegrapher from 1942 to 1945, despite the fact that her husband had been interned at the beginning of the war and that she was under suspicion.

In many cases such as these the announcement in the London Gazette simply reads ‘For services to the Allied cause’. This is the case for Etienne John Sutton, who was the Archivist at the British Consulate General in Paris when war broke out. Although he was recognised with an MBE few people will be aware of his gallantry. His recommendation reads:

‘After the invasion of Holland and Belgium, Mr Sutton volunteered to remain in Paris to look after British interests, whatever happened. He refused to be evacuated with the rest of the Consulate-General staff on the 12th of June 1940, and accepted charge of the last convoy of British subjects to St. Malo, which through force of circumstance never left Paris. Mr. Sutton re-opened the consular premises on 13th June to register British subjects stranded in Paris and to continue assistance to them, and on the 14th placed himself at the disposal of the United States Embassy for the same work.

Thanks to his efforts, a number of British subjects were enabled to cross the demarcation line into occupied France, thus avoiding imprisonment or internment. Arrested by the Germans on the 12th October 1940 on charges of espionage, he was sentenced on 17th March 1941 to solitary confinement for life. He spent two and a half years in solitary confinement prisons in France and Germany but was subsequently put to work in the prison tailors’ shop, where he received a sentence of 14 days close arrest for refusing to make munitions.

As a result of his hardships, Mr. Sutton fell seriously ill in the winter of 1943/4 and the rest of his imprisonment was spent in hospital. Transferred to the convict prison at Hamelin in September 1944, he was liberated there by the United States Ninth Army. He immediately took charge of his fellow prisoners’ interests and helped to organise their repatriation. Since July 1945 Mr. Sutton has been British Vice Consul at Strasbourg.’

SOE agents

The files also contain the recommendations for civilian awards for SOE agents such as Eileen Nearne, Yvonne Cormeau, Pearl Witherington and Odette Sansom. These brave women were dropped into enemy occupied France to act as wireless operators and to provide a line of communication between British intelligence and the French resistance. What they did would hardly be regarded as civil, but they were not put forward for military awards. Yet they were often involved in acts of sabotage and put their lives on the line to pass across vital information about enemy plans and movements, and to secure continuing supplies of arms and equipment.

The recommendation for Eileen Mary Nearne is in T 336/155. It says:

‘This Agent was landed in France by an aircraft in early February 1944, was W/T operator to a circuit in the Paris region. For five and a half months she maintained constant communication with London from this most dangerous area, and, by her cool efficiency, perseverance, and willingness to undergo any risk in order to carry out her work, made possible the successful organisation of her group and the delivery of large quantities of arms and equipment. She was arrested by the Gestapo towards the end of July 1944 while transmitting and was subsequently deported to Germany. She has since been released and returned to UK.’

This cataloguing project will help to bring acts of valour carried out by civilians in the Second World War to wider audience, helping us to engage with students and academics and family historians.

We have over 100 volunteers working at The National Archives engaged in a number of activities including enhancing catalogue descriptions of our Collection. I am grateful to the efforts of Sheila, Catherine and Liz for their sterling work on this project.

This article was originally published in The National Archives.

Articles you may also like

Henry the Seventh – Audiobook

HENRY THE SEVENTH – AUDIOBOOK By James Gairdner (1828 – 1912) Henry VII, the founder of the Tudor dynasty, less known than his son, Henry VIII, or granddaughter Elizabeth I, is often overlooked. This King toppled the ruling House that had held England’s throne for over four hundred years, the Plantagenets, and took a divided, war […]

The Battle of Greece – Australia’s Textbook Rear-Guard Action

Retreat doesn’t always mean defeat, sometimes it can be a victory to withdraw in good order and deny your enemy a total victory. This is was the outcome for the allied forces in Greece during April 1941, thanks in part to textbook rear-guard actions fought by Australian units, which allowed 50,732 men to escape the grasp of the advancing superior Axis force. But why were Australian units involved in Greece in the first place?

This article was first published by The National Archives. It is reproduced in accordance with the Open Government Licence v3.0.