Reading time: 5 minutes

The battle for France in 1940 is often portrayed as a rout: the German Wehrmacht simply trounced the French forces within a few weeks, crushing them with military might and tactical ingenuity. However, a few episodes debunk this image and the Battle of Stonne, where a small town in the Ardennes changed hands 17 times in three days, is one of the most prominent.

By Fergus O’Sullivan

The story of the Battle of France is fairly well-known. When the Germans invaded Poland in September 1939, Britain and France declared war, and then did pretty much nothing until May 1940. The French hid behind the Maginot line, figuring its forts and bunkers would be the rocks the German waves would crash upon. To the south and north were the Alps and Ardennes, respectively, two mountain ranges the French imagined the Germans couldn’t cross.

This was a terrible miscalculation, and the French were effectively poleaxed when the Germans came roaring out of the Ardennes via recently conquered Belgium in Fall Gelb (“Case Yellow”). Their main army encircled, the war was over before it even really began. The next few weeks are a story of retreat, rout and abject defeat.

However, what many popular histories gloss over is that the German invasion was a relatively close run thing at some critical points in time. The French army might not all have been state of the art, but it had solid equipment, some excellent leaders and plenty of soldiers motivated to defend their homeland.

The Battle of Sedan

One example of how things could have gone comes from the Battle of Sedan. Sedan is a small town nestled among the slopes of the Ardennes, just a few kilometres from the Belgian border. Because of its location, French high command thought it wouldn’t be likely to be attacked and hadn’t spent much effort in fortifying it.

Most of the French positions were on a ridge behind the town, and thus didn’t realise that the Germans had started to sneak tanks into the town on the night of May 12th, 1940. What they likely didn’t fail to notice was the Luftwaffe bombers who came screaming overhead the next day, pulverizing the defences. This was an almost textbook example of Blitzkrieg, overwhelming the enemy with sheer shock.

M108/9 14.5.1940 1. Panzer Reg. geht auf Pontonbrücke in Floing über die Maas, bei Sedan [Heeresfilmstelle Spandau-Ruhleben]

However, the French weren’t out of the fight yet and launched a series of counter offensives aiming to stop the German armored divisions. The first few, which were focused on the town of Bulson, weren’t effective, but French commanders soon set their sights on the village of Stonne, where the mountains provided a narrow and extremely defensible gap.

The Battle of Stonne

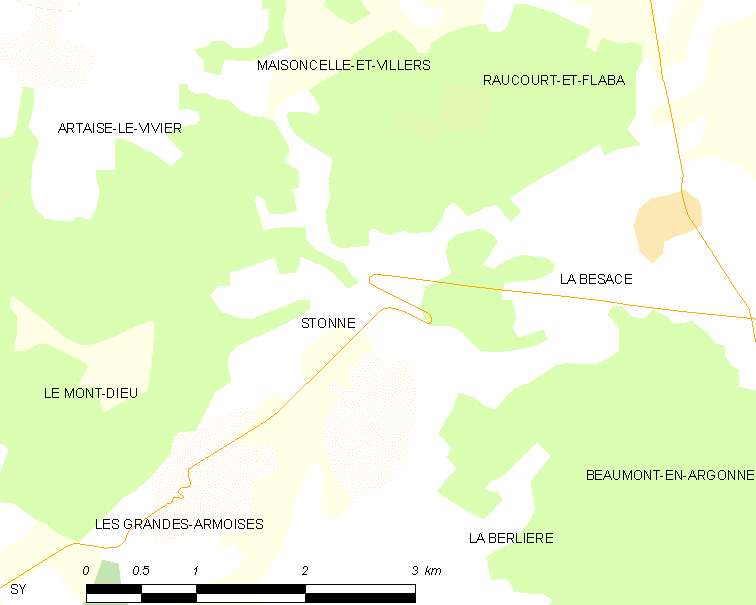

Stonne is even now a small village and likely wouldn’t have appeared in any history books were it not for its extremely strategic location. Any army barrelling south from Sedan has to pass through the small gap just north of the village.

On May 15th, the Germans managed to take the village, but almost immediately met a French counteroffensive. The fighting around Stonne was fierce, and over the course of the next three days, the town would change hands 17 times, until the Germans finally won the final victory on May 17th.

Pierre Billotte’s Wild Ride

This is amazing in and of itself, and shows the grit and determination of the French troops to not roll over in the face of the invader. However, what makes the battle of Stonne truly amazing is what has gone down in history as Piere Billotte’s wild ride.

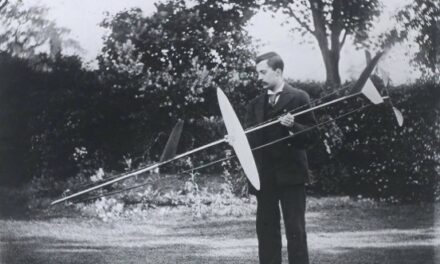

Billotte was the commander of a unit of six Char B1 heavy tanks, massive machines with even more massive guns and thick armour plating that could easily withstand the fire from the small-barrelled German panzers. In a tale of derring-do that could easily have come out of a novel, Billotte entered Stonne with just one vehicle, intending to flank the German forces there while his main force kept the Germans busy.

Imagine his surprise when he came upon a line of seven tanks, waiting to engage his forces. With the element of surprise on his side for once, Billotte made use of a tactic that would become popular among tank commanders of all sides during the war: he took out the lead and rear tanks in the column, leaving the other five easy pickings.

With the return fire from the German simply bouncing off his Char B1’s armor, Billotte and his crew made easy work of the initial seven tanks, before continuing and destroying another six throughout other parts of Stonne. This video goes into the details of that morning:

It was an amazing feat of arms, and left the Germans bloody. However, as brave and amazing as the attack was, it wouldn’t be enough: there were simply too many Germans. The next day, three of Billotte’s tanks were knocked out by concentrated fire and the defence of the town collapsed.

As fierce as the French fought, the element of surprise would prove too much to overcome, no matter the heroics of men like Pierre Billotte. Still, though, stories like the battle of Stonne prove that the fight was never as one-sided as popular history tends to portray.

Podcast episodes about the Battle of Stonne

Articles you may also like

Warfare spurred on the welfare state in the 20th century – but it probably won’t in future

The link between warfare and welfare is counter-intuitive. One is about violence and destruction, the other about altruism, support and care. Even the term “welfare state” – at least in the English-speaking world – was popularised as a progressive and democratic alternative to the Nazi “warfare state” during World War II. And yet, as new research shows, […]

Free of the Trench: How British & Imperial Forces Overcame the Deadlock of the Western Front

Reading time: 12 minutes

The First World War came to an end just over 100 years ago, a mere moment’s time in human history. But as close as we are to it, a century is more than enough to surround that conflict with myth and misconception.

The image of the war on the Western Front, as brought to us through decades of outdated scholarship and popular fiction, is simple: two vast armies, each equipped with the latest murderous fruits of the industrial age, found they couldn’t decisively defeat one another in the field and so settled into a long, bloody, dirty, and consumptive war in which thousands of lives were thrown away every day, often for minuscule gains which would bring neither side meaningfully closer to victory.

The real story is more complicated. By 1916, it was plain to see that tactics like those championed by Haig, designed to draw out the enemy for a momentous set-piece battle, weren’t working, and even those neck-deep in the fight didn’t need the benefit of hindsight to recognise that.

39th Militia Battalion and the Kokoda Track – Part 2

Reading time: 10 minutes

After the retreat from Kokoda, the battered survivors of B Company, 39th Battalion regrouped at the small village of Deniki. Major Allan Cameron, a 30th Brigade staff officer, arrived shortly after at Deniki on 4th August. Disgusted by the apparently ‘unsoldierly’ appearance of B Company, he jumped to the conclusion that these men must have run away from the fighting and had abandoned Kokoda for no reason. He sent them further back to Isurava in disgrace, depriving the remainder of the 39th of the only troops with battle experience. This wouldn’t be the last time that a textbook tactical withdrawal would be mistaken for cowardice. Cameron then decided that Kokoda must be recaptured.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks