Reading time: 9 minutes

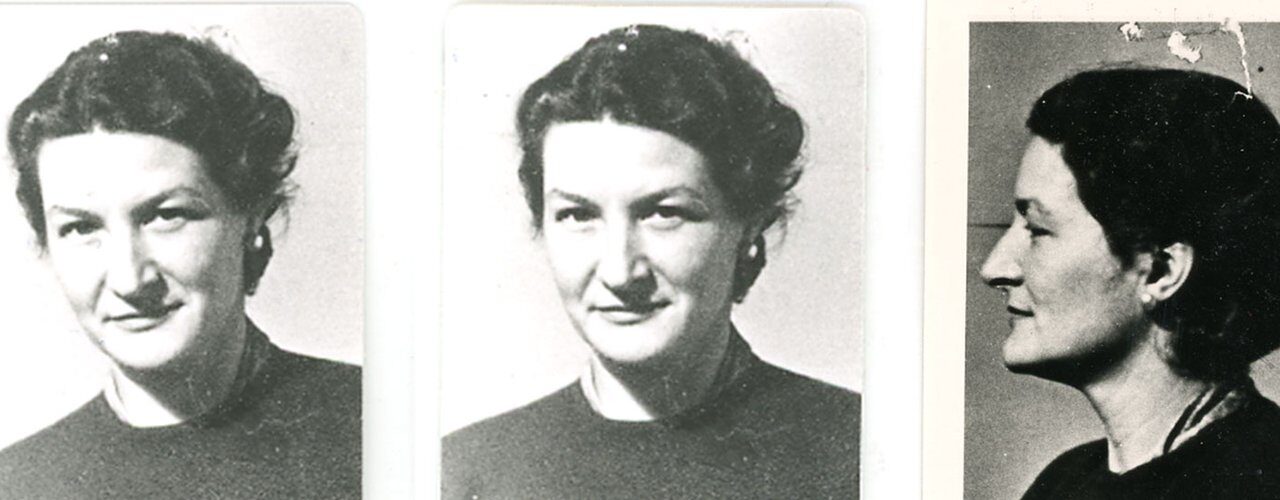

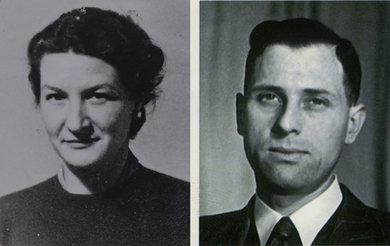

Virginia Hall (1906–1982) was an American woman who served with the British Special Operations Executive in France in 1941–1942. She then joined its US equivalent, the Office of Strategic Services, and became a founding member of the Central Intelligence Agency.

Early life

Virginia Hall was born in 1906 into a well-to-do Baltimore family. Her ambition in life was to work abroad for the American diplomatic service. This ambition was shattered when she accidentally injured herself in the foot while bird-shooting.

Her lower left leg was amputated when gangrene set in. This dashed her hopes of working for the diplomatic service as they wouldn’t, in those days, employ a person with an artificial limb. As she was going to use her artificial leg for the rest of her life, Virginia nicknamed it ‘Cuthbert’.

The early years of the war

Virginia was in France when the Nazis invaded, in May 1940. She volunteered for the ambulance service. After the fall of France she drove wounded French soldiers from the Haute Loire region to the larger military hospitals in Paris.

She had to apply for ration cards from the Nazis for petrol and food. Virginia noticed that, as an American neutral, and a woman, that officials treated her more generously than they treated the French drivers. She began to think about how she could help France.

After their defeat in the Battle for France, the British had withdrawn to Britain to hold out on their own. America was not to join the war for another 18 months. Virginia had seen fascism in action and could not simply sit by and wait for the war to end.

Virginia was making her way to London via Spain when she met a British agent, George Bellows, in the border town of Irun. He was impressed with her intelligence, courage, ability to take in what was going on around her and her passionate desire to help the French to fight the Nazis. He gave her the phone number of a friend in London. Eventually, bored in London, Virginia used the phone number Bellows had given her.

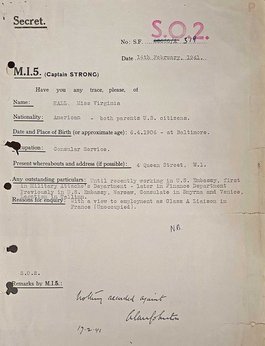

Recruitment as an agent

The ‘friend’ turned out to be Nicolas Bodington, an officer from ‘F’ Section of the Special Operations Executive (SOE). SOE was the newly founded British secret service dealing with sabotage and propaganda, and was looking to set up Resistance groups in Nazi-held territories.

At this stage SOE was struggling to find suitable personnel to be dropped into enemy territory to build Resistance circuits and networks. Bellows had calculated correctly that Virginia was just the sort of person they were looking for. Bodington immediately recommended her for service to his Head of Section. Virginia was offered a field job subject to the usual security check.

Virginia joined SOE in April 1941. After a rather brief and basic period of training she was sent to France in August 1941. Her cover was as a reporter for the New York Post which gave her a reason to travel around interviewing people and collecting information. She made herself inconspicuous by wearing less fashionable or eye-catching clothes. The information contained was relayed to London in the form of stories for the newspaper.

Pioneering work in France

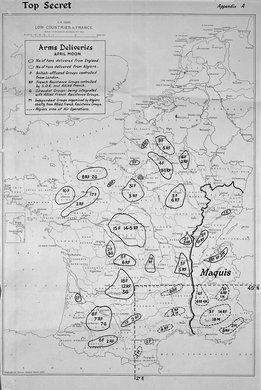

Virginia was very much a pioneer, being only the second woman SOE agent dropped into France, and the first to undertake an ongoing active field role. She organised contacts, meetings, circuits of Resistance members, drops of weapons and other supplies and helped escaping Allied airmen get back to London and back into the war.

Her work ranged across the Unoccupied Zone in the southern half of France. Her headquarters were in Lyon, which was the centre for the French Resistance. An American diplomat in the US Consulate in Lyon also allowed her to use their diplomatic bag to relay information to London. Escaping allied airman were told to make for the Consulate and ask for ‘Olivier’, who was Virginia.

Virginia was cautious in her work and observed the rules of security required in the field. Her ability to do this is attested to by the length of time and amount of work she was able to take. She did not leave France again until September 1942. Long before then, the French had begun to know her as ‘la dame qui boite’, while the Germans also dubbed her ‘the limping lady’, and put her on their most wanted list.

Running a ‘circuit’

The SOE circuit that Virginia founded was called HECKLER, and her codename was DIANE. At first it was a matter of finding co-resistors in Lyon. Her two closest were a doctor, Jean Rousset, and Germaine Guerin, the owner of one of the most renowned brothels in Lyon. Germaine provided several safe houses and passed on information gained by her girls from their German clients.

Virginia simply avoided or ignored SOE agents she considered a security risk. This included Jean Georges Duboudin, the man she was supposed to work for. When SOE objected, Virginia told them to ‘lay off!’

Invited to a meeting in Marseilles at which various SOE agents and Resistance notables would be present, Virginia’s survival instinct led her not to attend. She was concerned that too many SOE and Resistance people would be in the same place at the same time. She did not think everyone took security procedures seriously enough.

Sure enough, the Gestapo raided the meeting and captured 12 SOE agents and French Resistance organisers. As a result Virginia was the only SOE agent at liberty, and the only one with a radio able to communicate with London. The work developed well and she co-ordinated or became the link between various Resistance groups or networks.

Although Virginia carried on with all her other work for the Resistance the fate of these prisoners and attempting to engineer their escape remained one of her key pre-occupations.

Freeing the prisoners

With the expansion of her contacts and as her renown in helping allied airmen escape increased, so too did the risks. The Gestapo had long seen Lyon as the key centre of Resistance activity. Even before Operation Torch, the Allied landings in North Africa, the Germans had moved a lot more agents into the Unoccupied Zone. Time was running out for Virginia. She focused on freeing the 12 SOE and Resistance prisoners, now transferred to Mauzac prison, near Bergerac.

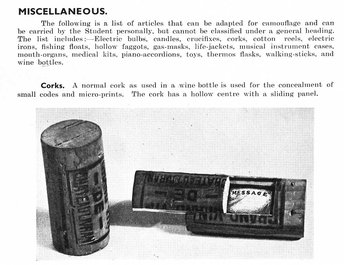

Wireless Operator Georges Begue found a way to smuggle notes out to Virginia. She recruited Gaby Bloch, the wife of one of the prisoners, to smuggle messages and tools concealed in tins of sardines to the prisoners. Begue made a key to the door of the building the prisoners were held in.

Virginia acquired safe houses, transport, helpers, and two French Police uniforms for use in the escape. The prisoners escaped on 15 July 1942. After a period in hiding they met up with Virginia in Lyon, from where they made their way back to England via Spain. This was a very productive operation, as several of the escapers returned to France to play key roles in leading SOE or Resistance groups.

A House in the Mountains: The Women Who Liberated Italy from Fascism – Book

By Caroline Moorehead The acclaimed author of A Train in Winter returns with the “moving finale” (The Economist) of her Resistance Quartet—the powerful and inspiring true story of the women of the partisan resistance who fought against Italy’s fascist regime during World War II. In the late summer of 1943, when Italy broke with the…

Only 3 left in stock

Escaping and later work

The Nazis were furious about the escape and put extra resources into hunting down those responsible. The Sicherheitsdienst (the SS Intelligence Service) and Gestapo moved 500 extra agents into the Unoccupied Zone, with the focus on Lyon. Virginia had up until then been protected by senior police contacts. This was no longer possible with the German security services in the South in such numbers.

In August it became clear that the French Resistance network around Paris, GLORIA, had been infiltrated. A man disguised as a priest, calling himself Robert Alesch, visited Virginia claiming to be an agent of GLORIA. Virginia had concerns about him being a German agent when the news of the capture of GLORIA’s members came through. She anticipated further, heavier manhunts, and left Lyon without telling her local contacts – even Jean Rousset or Germaine Guerin.

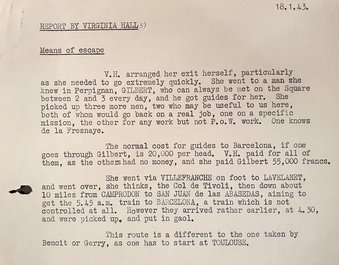

To make her escape Virginia travelled by train to Perpignan and then crossed the Pyrenees via a 7,500 foot high pass, walking up to 50 miles in a day. This was done in great discomfort as ‘Cuthbert’ (her wooden leg) dug into her stump and turned it to a bloody mess.

When she had contacted SOE to tell them of her pending escape, Virginia mentioned that she planned to cross the Pyrenees on foot and hoped that Cuthbert would not be ‘bothersome’. SOE did not understand this and simply replied ‘If Cuthbert troublesome, eliminate him’!

The Office of Strategic Services

Arriving in Spain, Virginia was arrested for crossing the border illegally, but the US Embassy secured her release. Returning to London and SOE she found that Maurice Buckmaster, the Head of SOE’s ‘F’ Section, refused to allow her to return to France as he considered her too compromised.

Instead, she joined the also recently formed American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and returned to France to continue in the same organising role, in the process creating the SAINT spy network.

Later Virginia was decorated with the Distinguished Service Cross by US General William ‘Wild Bill’ Donovan, the head of the OSS, in addition to the MBE she had already earned from Britain, and the Croix de Guerre she would go on to receive from France. She went on to work for the CIA until 1966.

Since August 1942, when this lady went into the field on our behalf, she has devoted herself whole-heartedly to our work without regard to the dangerous position in which her activities would place her if they were revealed by the Vichy authorities.

She has been indefatigable in her constant support and assistance for our agents, combining a high degree of organising ability with a clear-sighted appreciation of our needs. She has become a vital link between ourselves and various operational groups in the field, and her service for us cannot be too highly praised.

Recommendation for Virginia Hall to receive the Croix de Guerre. Catalogue reference: HS 9/647/4

After the war the newer espionage and counter-espionage officials who mainly performed desk duties did not appreciate her abilities and energy, or what she had been responsible for during the Second World War. Only from the 1970s onwards has her reputation grown and due respect been accorded to her and her wartime record.

This article was originally posted to The National Archives.

Podcasts about Virgina Hall

Articles you may also like:

Australia’s first action in the Pacific in World War II a valiant catastrophe – Video

Just before midnight on 7 December 1941, Flying Officer Peter Gibbes stepped off the train at Kota Bharu on the coast of northeast Malaya after a long, tiring journey up the peninsula from Singapore. Gibbes, an airline pilot in peacetime, had been newly posted to the Royal Australian Air Force’s 1 Squadron, which in the ensuing hours would become the first Australian military unit to see action in the Pacific War.

Weekly History Quiz No.258

1. When did the Spanish Empire reach its greatest extent?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

General History Quiz 176

1. How long did the Berlin Wall stand?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

This article was first published by The National Archives. It is reproduced in accordance with the Open Government Licence v3.0.