Reading time: 5 minutes

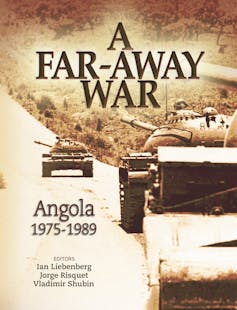

The book A Far-Away War: Angola 1975 – 1989, about the war waged by apartheid South Africa against its neighbour, has attracted the attention of historians and those who fought in it.

More than a quarter of a century after it ended, the war is still remembered by many who were touched by it in one way or other.

By Dries Velthuizen, University of South Africa

The war in Angola and Namibia (which was ruled by South Africa at the time) took place from 1966 to 1989. Highly internationalised, it was seen as a proxy for the rivalry between the then two super powers. The Soviet Union backed the communist-leaning MPLA government while the US supported the rebel Unita movement.

Intertwined in it were several internal wars:

- the Angolan War of Independence,

- the Angolan Civil War,

- the Namibian War of Independence, and

- the struggle against apartheid in South Africa.

The overall objective of the book is to offer “new voices” and “other views” on the “Border War/Bush War” and its outcomes. It adds some important insights to “bush war literature”, which has become a popular genre of literature in its own right in South Africa and elsewhere.

Through thorough research, the work attempts to fill an important gap in literature that remains dominated by former members of the South African Defence Force. This includes retired senior officers, “foot soldiers” as well as armchair militarists who depict the war as a kind of adventure.

Different perspectives

The book is written by several authors. They include:

- Ian Liebenberg, a South African academic and conscientious objector. He is also one of the editors;

- Jorge Risquet, a Cuban politician, diplomat and participant during the war, and

- Vladimir Shubin, a Russian academic.

The book is not the first publication on the theme by the authors. It consolidates work by the two prominent academics, Shubin and Liebenberg, with significant value added by other academics and journalists from Cuba, Germany and South Africa.

The chapters are written from the perspective of lived experiences of the narrators. This gives it a flavour of credibility. It does so without claiming complete knowledge of all events that took place on political, strategic and tactical levels.

Although the title draws attention to Angola, the international and regional setting of the conflict inevitably leads to narratives of events in South Africa and Namibia. To a lesser extent events in other countries in southern Africa and abroad are also recounted.

The authors emphasise at the outset that they cannot claim ownership to the truth of what happened during the war in Angola. The aim of the book is therefore to allow different voices, experiences and interpretation of experiences, inviting further discourse.

A core theme of the book is that apartheid South Africa’s politicians started a war in which they could not maintain a strategic advantage despite some operational successes and suitable tactics. The reason for this was that they misread the quest for national liberation and international opinion that undermined their effectiveness on other levels.

The chapter on Cuba’s involvement in Angola describes the extensive military involvement of the Caribbean island and how it eventually succeeded in countering South African military intervention.

The historic narrative about relations between Russia and South Africa explains how the two countries became involved with each other militarily on two occasions in the last century – during the Anglo-Boer War and the war in Angola.

The following chapter discusses the Soviet Union’s involvement in Angola. It makes the point that the war was not merely a reaction to apartheid, imperialism and colonialism, but that it was part of a violent contest between the two super powers: the Soviet Union and its allies, and the US and its allies.

The chapter detailing East German support for the liberation armies in Angola teases out this perspective quite clearly.

The chapter on resistance to conscription in South Africa succinctly describes how South Africans broke away from a militarised society to help end the war in Angola as well as white hegemony in South Africa.

The book reminds us of a sad era in which, to oppose apartheid, many in Africa had to find common cause with foreign forces such as the Soviet Union, East Germany and Cuba. All these countries came to Africa with their own ideologies, interests and agendas as well as histories of gross human rights violations.

The book concludes with some insightful pictures and an extensive bibliography, an invaluable asset for researchers and other scholars.

A visible gap are the narratives of African participants in the war, most notably Angolan authors as well as veterans from the Namibian and South African liberation movements.

Otherwise this is a well-researched, well written book that provides a perspective that adds value to the existing body of knowledge on the “Bush War”. It provides credible alternatives to existing dominant views. The book is well worth reading for scholars, military and diplomacy practitioners as well as war veterans.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about South-African war in Angola

Articles you may also like

The discovery of the lost city of ‘the Dazzling Aten’ will offer vital clues about domestic and urban life in Ancient Egypt

Reading time: 5 minutes

Built by Amenhotep III and then used by his grandson Tutankhamen, the ruins of the city were an accidental discovery. In September last year, Hawass and his team were searching for a mortuary temple of Tutankhamen.

From micro to macro, Andrew Leigh’s accessible history covers the economic essentials

Reading time: 6 minutes

Andrew Leigh’s The Shortest History of Economics is the latest in a series of such histories, mostly focused on particular countries.

It begins with a striking mini-history of household lighting, focusing on the amount of labour required to produce the light now given off by a standard lightbulb: 58 hours for a wood fire, five hours for a candle based on animal fat, a few minutes for an early electric lightbulb, and less than one second for a modern light-emitting diode.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.