Reading time: 5 minutes

Success for women often comes at a cost. Award-winning, election-winning and high-earning women are more likely to be divorced in a strange trend that may affect other aspects of our lives.

However, divorce may not be the price for success, but a remnant of our convict past. Attitudes and ideas outlive generations, meaning misfortunes for successful women could be a symptom of history.

By Pauline Grosjean, UNSW Sydney

The ‘Oscar curse’: success and divorce

The “Oscar curse” refers to the fact that for a woman winning an Academy Award, it likely means getting a divorce. The same is not true for men. This curse affects other successful women, such as female politicians after they win an election.

In a recent paper, Marianne Bertrand and her co-authors showed, in a representative sample of Americans, that when women started making even just a little bit more money than their husbands, divorce was likely to follow. Women who have the potential to make more money than their husbands, due to their level of education for example, are less likely to be married. When these women do marry, they “act wife” by reducing their hours in the workplace – and their income as a result – and by doing more housework.

Similarly, in Australia, just 60% of men and women disagree with the statement “it is not good for a relationship if the woman earns more than the man”. There is no noticeable difference between men and women, and responses have hardly changed since the HILDA survey first measured these attitudes in 2005. This raises the questions of where such norms come from and why they are so persistent.

Convicts and conservative attitudes

We may have to turn to our past for answers. In a forthcoming paper, for the Review of Economic Studies, Rose Khattar and I show that Australia’s convict past still exercises a strong and pervasive influence on gender norms, marriage and work in the country today.

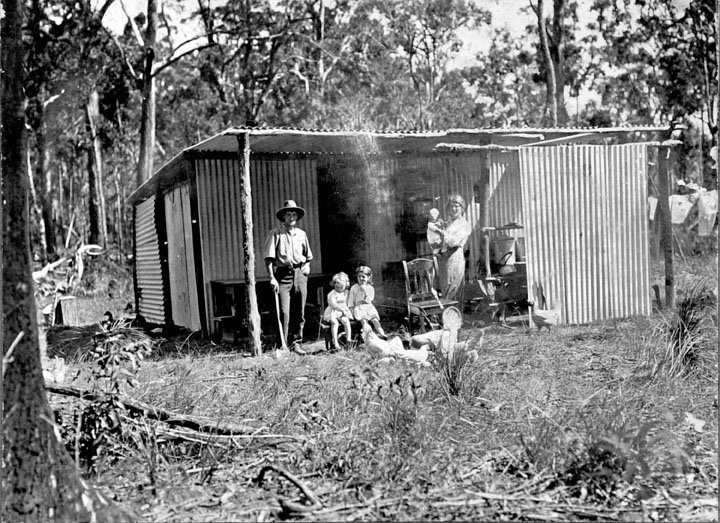

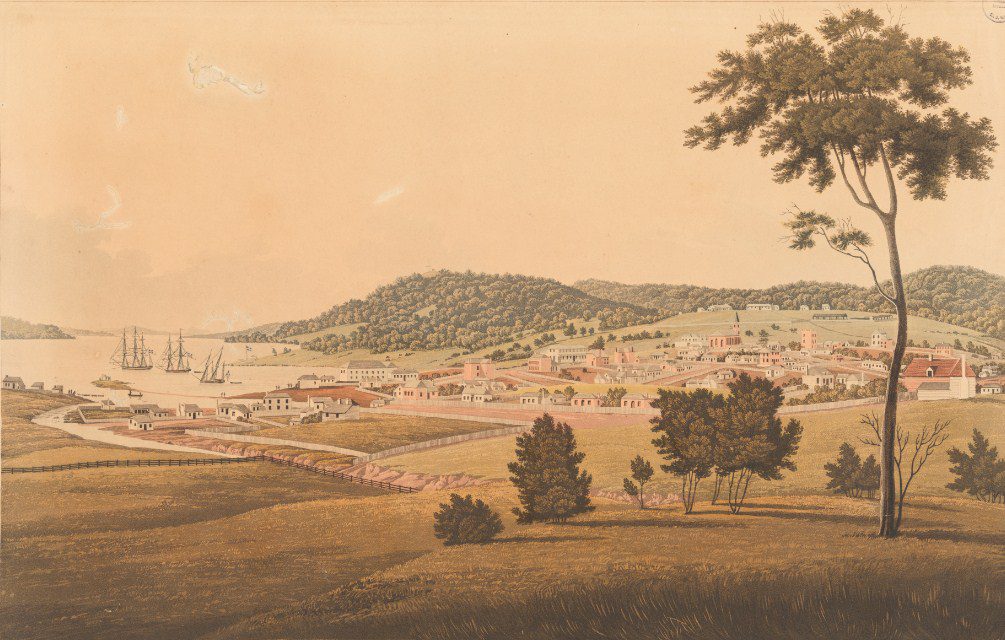

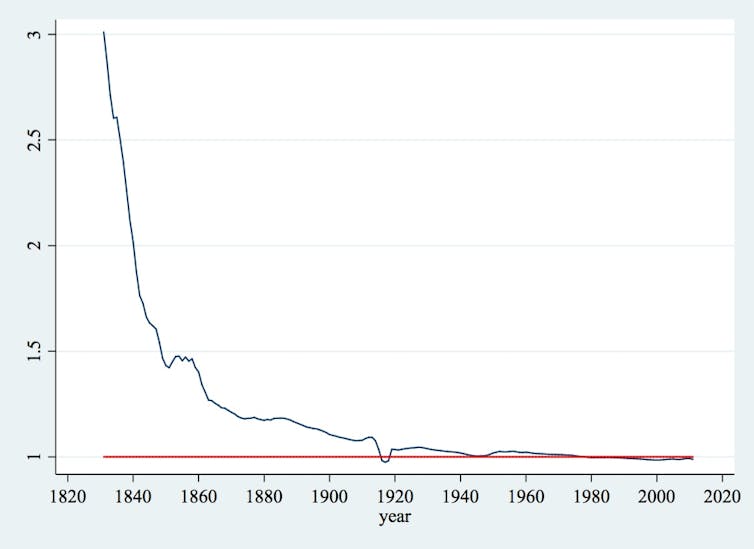

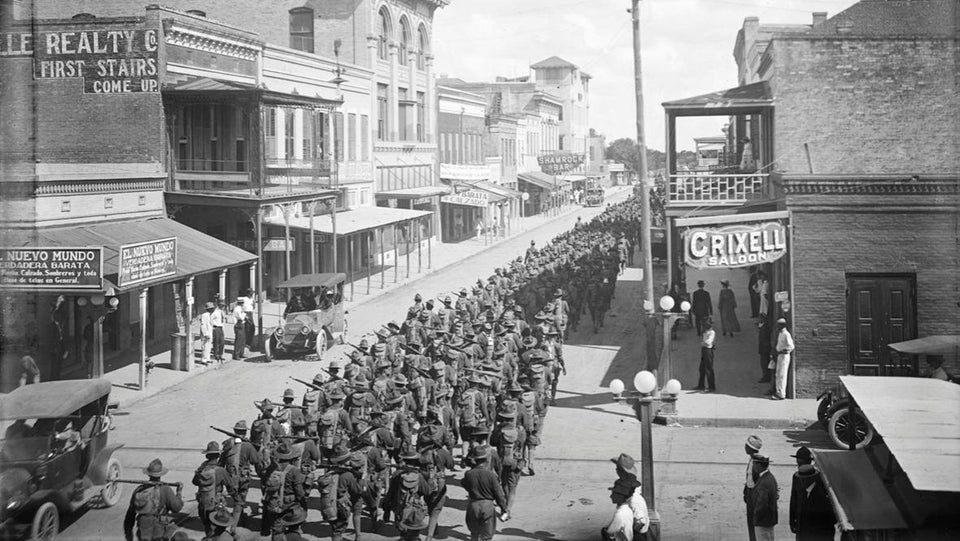

It is not the presence of convicts that matters, but the drastic distortion in the ratio of men to women that came with it. Convict men outnumbered convict women by roughly six to one. These numbers were even more skewed at the start of settlement. Convicts were joined by free migrants, especially in the second half of the 19th century, whose numbers also skewed heavily male. The ratio of men to women was consistently skewed in favour of males in Australia until the start of the first world war.

We show that in areas of Australia that were more male-biased in the past, people are more likely to hold conservative attitudes towards gender-respective roles at home and in the workplace. In those areas, women today are less likely to work. When they do work, they work fewer hours and are more likely to work part-time rather than full-time.

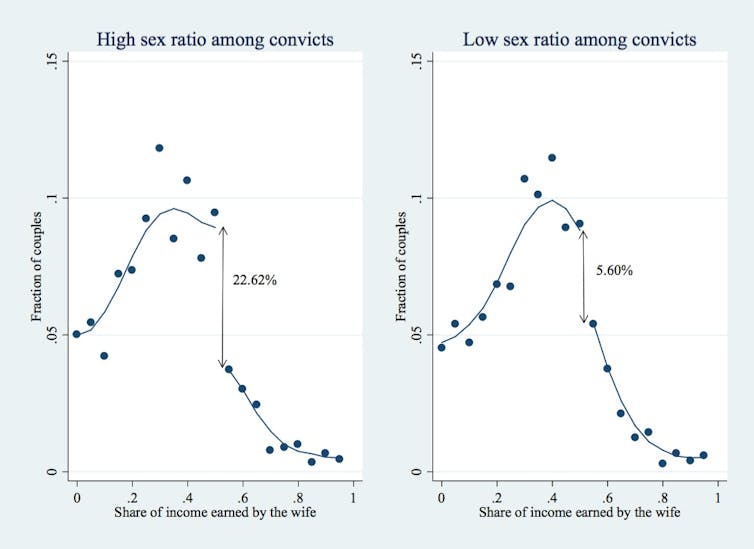

Probably as a consequence of more conservative attitudes and fewer hours worked, women are less likely to progress to high-ranking occupations. As shown in the graph below, relationships in which women earn more money than their husbands are a rare thing. This is true overall in Australia, but particularly so in areas where the ratio of convict men to convict women was above the median.

In the vast majority of marriages, the husband makes more money than his wife. As shown by Figure 2, as soon a woman’s income starts to exceed a man’s, the likelihood of a relationship – either by divorce or by not getting married in the first place – drops significantly.

This drop is much higher (more than 22%) in areas that were more male-biased in the past (left panel), compared with areas that were more balanced (less than 6% more men) (right panel).

Convicts and the marriage market

While women in areas that were more male-biased do less paid work, they also enjoy more hours of leisure time than women in other parts of the country. Women today in areas that were more male-biased in the past work fewer hours in the workplace, but do not do more at home. Instead, they enjoy more free time.

We suggest this is a holdover from an era in which the marriage market for women among Australia’s European population was imbalanced in favour of women. Given potential female marriage partners were in short supply, women in those areas may have had more negotiating power in the home and used it to enjoy more free time and work less, especially given that the labour market was not very favourable to women in 19th-century Australia.

Such behaviours and attitudes were then transmitted from parents to children, and persist until today.

It is also important to note that these behaviours and attitudes are related only to gender roles at home and in the workplace: we did not find any evidence of elevated misogyny in areas that were more male-biased in the past.

Effects of biased sex ratios, which persist well after sex ratios have returned to their natural level, matter for places with lopsided gender ratios.

There are an estimated 100 million missing women in the world today, for instance, mostly in China and India, as a result of sex-selective abortions and inferior nutrition and care for girls and women. As Australia proves, the consequences of unbalanced societies can last for decades to come, for better or worse.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Articles you may also like

Whose History? AI Uncovers Who Gets Attention in High School Textbooks

Natural language processing reveals huge differences in how Texas history textbooks treat men, women, and people of color. Hispanic students make up 52 percent of enrollments in Texas schools, for example, but Hispanic people received almost no mention at all in any of the textbooks — less than one-quarter of one percent of people who […]

A new narrative unfolds about South Africa’s protracted war in Angola

Reading time: 5 minutes

The book A Far-Away War: Angola 1975 – 1989, about the war waged by apartheid South Africa against its neighbour, has attracted the attention of historians and those who fought in it. More than a quarter of a century after it ended, the war is still remembered by many who were touched by it in one way or other.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.