Reading time: 8 minutes

The horror film genre has a long and celebrated history which now dates some 100 plus years; from the silent masterpieces like Nosferatu (1922), the iconic monster pictures like The Mummy (1932) and Frankenstein (1931), the 1980s slasher hits like A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), and to such modern entries like Saw (2004), what has united these varied films is their foundation on the element of fear. Yet for all the titles on this lengthy list, one film in particular has created a lasting legacy of genuine fright, unease, disturbance, controversy, and haunting imagery that has never been replicated.

By Michael Vecchio

2023 marks the 50th anniversary of director William Friedkin’s The Exorcist, released to theaters on December 26, 1973, and which has since been widely considered the scariest movie of all time. Downright frightening and often simply disturbing in nature, what has ultimately made The Exorcist so memorable and lasting for the last fifty years is not simple jump scares but an emotionally intelligent examination of the immemorial battle between good and evil. Indeed regardless of its setting (1970s Washington DC) and religious background (Catholicism), there is a certain sense of universality to this story of a possessed 12 year old girl. Beyond one’s cultural upbringing, religious belief, or generational values, the tale of confronting evil against malice incarnate is really an ageless account.

Combined with terrific special practical effects (which in a modern world of computer wizardry has been sadly lost), compelling lead performances, an incisive screenplay, and a bold audacity to tackle such dark subject matter, The Exorcist is undoubtedly a masterpiece not just in its genre, but across all of cinema. Beyond being merely a fictional story however, the historicity of demonic possession and efforts to combat it (exorcism and other rituals) elevate the film to a level of sophistication not often associated with the horror genre.

It was a historic background that enticed emerging novelist William Peter Blatty (1928-2017) to craft a story that although featured fictional characters, was very much based on real events and centuries of history. Indeed with the publication of the novel The Exorcist in 1971, much of the general public encountered for the first time the idea of exorcism and its very real manifestations. Besides the fantastical elements of the novel (and later film), what was revealed in this story was a spotlight on the seldom discussed (or believed) episodes of spiritual possession.

READ MORE: REMEMBERING WILLIAM PETER BLATTY

Though more than half of all Americans identify with one Christian denomination, addressing the presence of the Devil has often been indirectly avoided. While it has been unofficially stated that “If you believe in God, you must believe in the Devil”, very few if any religious books, films, or other works for mass consumption openly discussed Satan. Thus Blatty’s novel shocked many readers not solely for its dark content, but for simply bringing forward the notion of the Devil as a real world antagonist.

It was in fact an actual case of alleged demonic possession in 1949 of a 14 year old boy, that directly inspired Blatty. Attended to by several Catholic priests, urban legends began to develop, and much mystery and supernatural elements soon enveloped the tale. While Blatty certainly incorporated much of the mythos to suit his novel, the fact that an exorcism was performed is anything but fantasy. Many of the major faiths of the world from East Asia, the Middle East, Africa, the Caribbean, and even Oceania have discussed demonic possession and different forms of casting out evil spirits since ancient times. Islam and Christianity both explicitly address such possession in their respective schools of theology in a field known as demonology and through the centuries the Devil appeared in numerous artistic works. In the context of Christianity, and particularly the Catholic Church, instances of Jesus expelling demons are mentioned several times in the New Testament, and the modern practice of performing exorcism in the “name of Jesus Christ” has been recorded as early as the 15th century.

Indeed the Vatican first issued official guidelines on exorcism back in 1614 and only revised them in 1999! Whether or not people were actually “possessed” by a demon or suffered from another mental or physical disturbance, the act of exorcising another remained a relatively common, if seldom publicly acknowledged rite of the Church. For many skeptics, reports of the supernatural elements of many exorcisms, further cemented convictions that exorcisms like the faith itself could not be grounded in rational thought.

Adding to the dubious effectiveness of such a ritual, were the many deaths that resulted during or after attempted exorcisms that led to outcries that the act was criminal behaviour from Church hierarchy. Perhaps one of the most well known instances occurred in 1976 (three years after The Exorcist was theatrically released), when a 23 year old German woman died of malnutrition after some 67 exorcisms in the span of one year. For their role, two Catholic priests and the girl’s parents were sentenced to six months in prison for negligent homicide. Today all medical explanations, especially mental illness, must be explicitly ruled out before the Catholic Church sanctions a potential exorcism, but thanks to The Exorcist and now other related films and literature the entire ritual has become ingrained in public recognition.

This was certainly not the case at the time of William Peter Blatty’s novel, and with director William Friedkin’s (1935-2023) groundbreaking film. Demonic possession and the act of an exorcism were not exactly common points of discussion, but with the combination of Blatty’s source material and the audacious vision of Friedkin, what was presented to audiences in December 1973 would fundamentally change the public discourse. Like any important work of art, whether one subjectively likes or dislikes The Exorcist is beyond the point; here is a film that in its innate controversial nature has generated discussion, revulsion, and admiration for 50 years and counting proving itself as a truly lasting masterpiece.

Selected for preservation in the United States’ Library of Congress, it became the first horror film to be nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture. With a total of ten nominations that also included Best Director and Supporting Actress, it would go on to win for Best Sound and for Blatty’s Adapted Screenplay. Though there were numerous reports of theatre goers fainting, vomiting, and having to leave their screenings, the imagery of The Exorcist has now become a fixed staple of the American film industry.

From its eerie use of British musician Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells as its main theme, to the corrupted face of a levitating and profanity spewing 12 year old Regan, and its now quotable lines like “The Power of Christ compels you”, there can be no doubt that even those who have not seen the film will surely be familiar with it. In the ensuring decades numerous direct sequels and other films related to possession have emerged (as recently as 2023’s The Exorcist: Believer). However these have only served to water down the effectiveness of the original by not only overexposing the concept of an exorcism but eliminating its prime fear factor: the fully unknown nature of Satan.

If the Devil is now a common cinematic villain, it was not so back in 1973. Together William Friedkin and William Peter Blatty did not hold back in presenting a narrative that aimed to shock audiences as much as it entertained them. A pioneer of the New Hollywood movement of directors that would include names like George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and Martin Scorsese, Friedkin’s raw and graphic portrayal of Blatty’s bold story had many viewers and studio executives unprepared. Not only is the very concept of the narrative disturbing, but its visual representation of a young girl’s possession and the struggles of her mother, doctors, and the priests attending to her are raw and visceral.

The outright scary dramatisation of what a potential demonic haunting could look like rightfully startled the public, for some the demonic possession of an innocent girl seemed to also stand as an allegory for the tumultuous 60s decade in America and controversial episodes like the war in Vietnam.

And so 50 years have now passed since the theatrical release of The Exorcist, and it continues to have resonance in Western popular culture half a century later. By presenting unsettling images and themes in a wrapping of the timeless lens of good and evil, the film marked a watershed moment in the evolution of horror cinema. While its sheer raw impact may have diminished through the decades, The Exorcist remains an audacious work of art that beyond just cinematic analysis made many question their beliefs. The presence of the Devil and his influence is certainly nothing new to any major world religion, but to visually see what his corrupting power could do through means of movie magic understandably left quite an impression on audiences. For tackling such subject matter, openly challenging the viewing public, and boldly creating a work of film quite unlike any other, The Exorcist and its makers have ensured that like the supernatural possessor in its story, their film truly exists without age.

Podcasts about The Exorcist

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 152

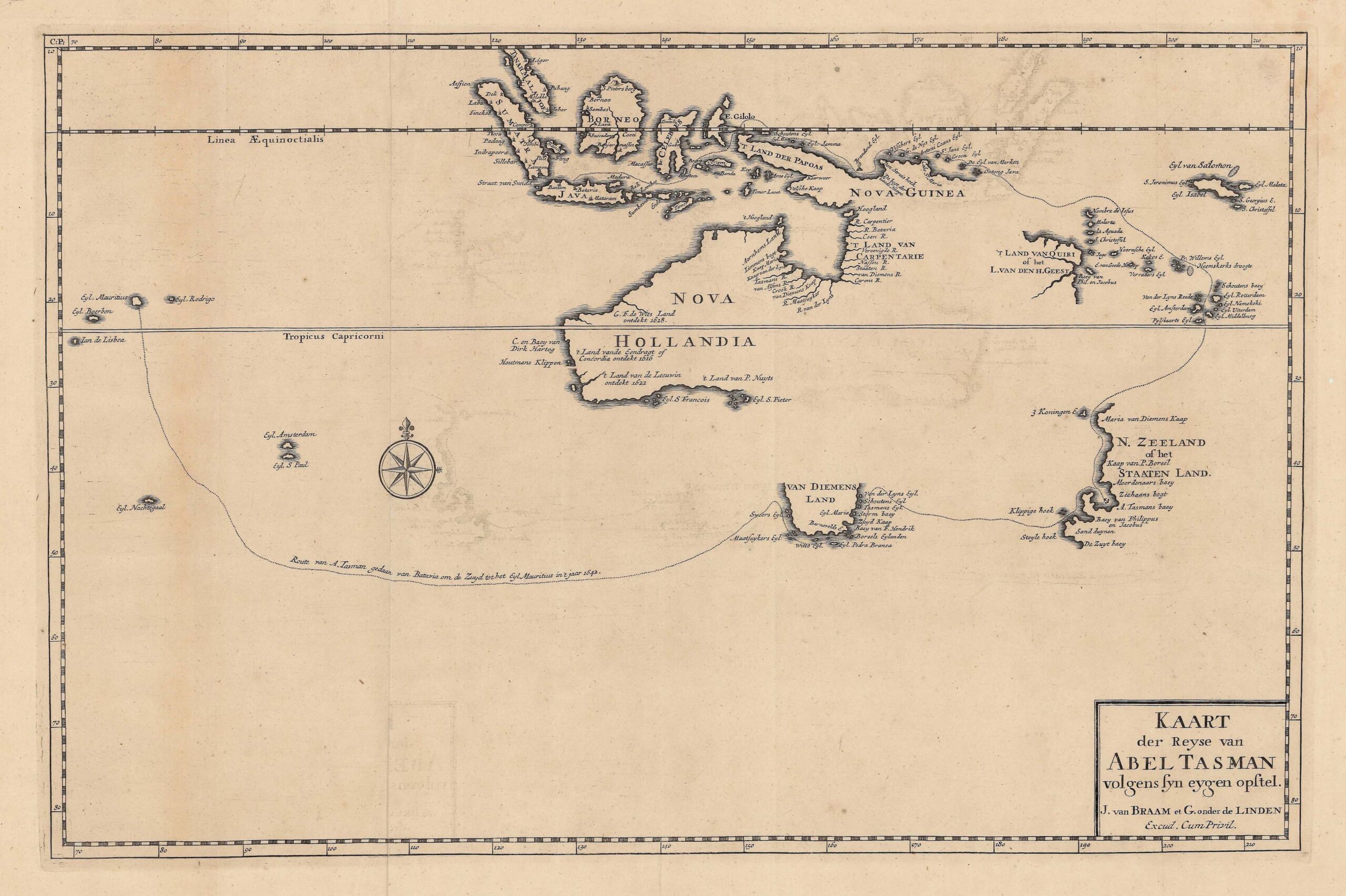

1. When did the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman become the first European to reach New Zealand?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.