Reading time: 6 minutes

An almost 3,400-year-old industrial, royal metropolis, “the Dazzling Aten”, has been found on the west bank of the Nile near the modern day city of Luxor.

Announced last week by the famed Egyptian archaeologist Dr Zahi Hawass, the find has been compared in importance to the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb almost a century earlier.

By Anna M. Kotarba-Morley, Flinders University

Built by Amenhotep III and then used by his grandson Tutankhamen, the ruins of the city were an accidental discovery. In September last year, Hawass and his team were searching for a mortuary temple of Tutankhamen.

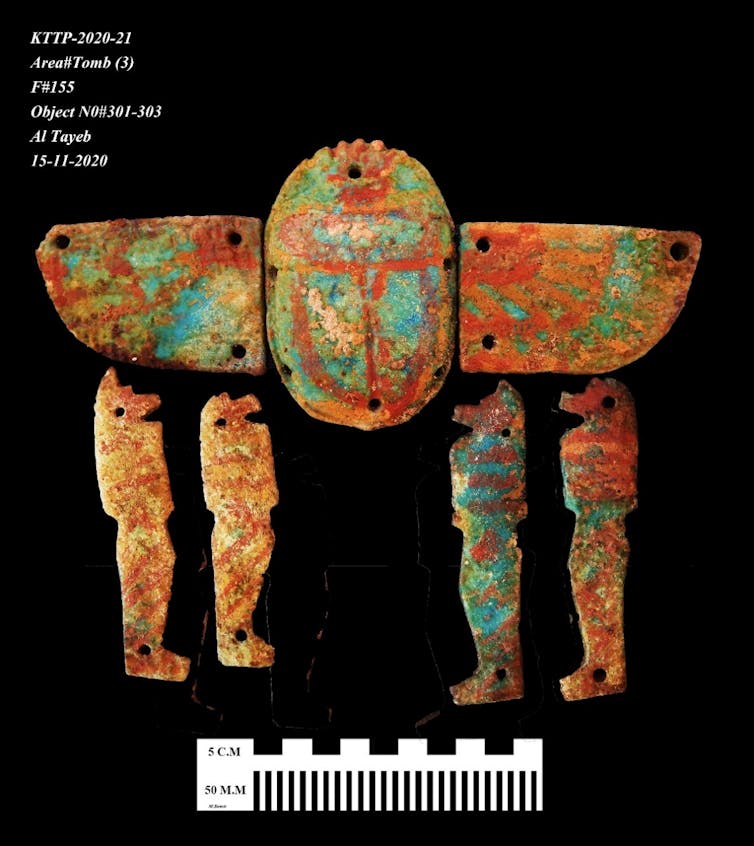

Instead, hidden under the sands for almost three and a half millennia, they found the Dazzling Aten, believed to be the largest city discovered in Egypt and, importantly, dated to the height of Egyptian civilisation. So far, Hawass’ excavations have unearthed rooms filled with tools and objects of daily life such as pottery and jewellery, a large bakery, kitchens and a cemetery.

The city also includes workshops and industrial, administrative and residential areas, as well as, to date, three palaces.

Ancient Egypt has been called the “civilisation without cities”. What we know about it comes mostly from tombs and temples, whilst other great civilisations of the Bronze Age, such as Mesopotamia, are famous for their great cities.

The Dazzling Aten is extraordinary not only for its size and level of prosperity but also its excellent state of preservation, leading many to call it the “Pompeii of Ancient Egypt”.

The rule of Amenhotep III was one of the wealthiest periods in Egyptian history. This city will be of immeasurable importance to the scholarship of archaeologists and Egyptologists, who for centuries have struggled with understanding the specifics of urban, domestic life in the Pharaonic period.

Foundations of urban life

I teach a university subject on the foundations of urban life, and it always comes as a surprise to my students how little we know about urbanism in ancient Egypt.

The first great cities, and with them the first great civilisations, emerged along the fertile valleys of great rivers in Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq), the Indus Valley (modern day India and Pakistan) and China at the beginning of the Bronze Age, at least 5,000 years ago.

Just like cities today, they provided public infrastructure and roads, and often access to sanitation, education, health care and welfare. Their residents specialised in particular professions, paid taxes and had to obey laws.

But the Nile did not support the urban lifestyle in the same way as the rivers of other great civilisations. It had a reliable flood pattern and thus the second longest river in the world could be easily tamed, allowing for simple methods of irrigation that did not require complex engineering and large groups of workers to maintain. This meant the population didn’t necessarily need to cluster in organised cities.

Excavations of Early Dynastic (c. 3150-2680 BCE) Egyptian cities such as Nagada and Hierakonpolis have provided us with a plethora of information regarding urban life in the early Bronze Age . But they are separated from the Dazzling Aten by some 1,600 years — as long as separates us from the Huns of Attila attacking ancient Rome.

One city closer in age to the Dazzling Aten we do know a little more about is the short-lived capital of Amenhotep’s III son, Akhenaten, known as the “Horizon of the Aten”, or Tell el-Amarna. Amarna was functional for only 14 years (1346-1332 BCE) before being abandoned forever. It was first described by a travelling Jesuit monk in 1714 and has been excavated on and off for the last 100 years.

Very few other Egyptian cities from the Early Dynastic Period (3150 BCE) to the Hellenistic period (following Alexander the Great’s conquest of Egypt in 332 BCE), have been excavated. This means that domestic urban life and urban planning have long been contentious research areas in the study of Pharaonic Egypt.

The scientific community is impatiently waiting for more information to draw comparisons between Akhenaten’s city and the newly discovered capital founded by his father.

The magnificent pharaoh

Amenhotep III, also known as Amenhotep the Magnificent, ruled between 1386 and 1349 BCE and was one of the most prosperous rulers in the Egyptian history.

During his reign as the ninth pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty, Egypt achieved the height of its international power, climbing to an unprecedented level of economic prosperity and artistic splendour. His vision of greatness was immortalised in his great capital, which is believed to have been later used by at least Tutankhamen and Ay.

In 2008, for the first time in history, the majority of world’s inhabitants lived in the cities. Yet, with globalisation, the differences between the “liveability” of modern cities are striking.

As a society we need to understand where cities come from, how have they formed and how they shaped the development of past urban communities to learn lessons for the future. We look forward to research and findings being published from the ancient city of Amenhotep III to enlighten us about the daily lives of ancient Egyptians at their height.

Podcasts about Aten

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 110

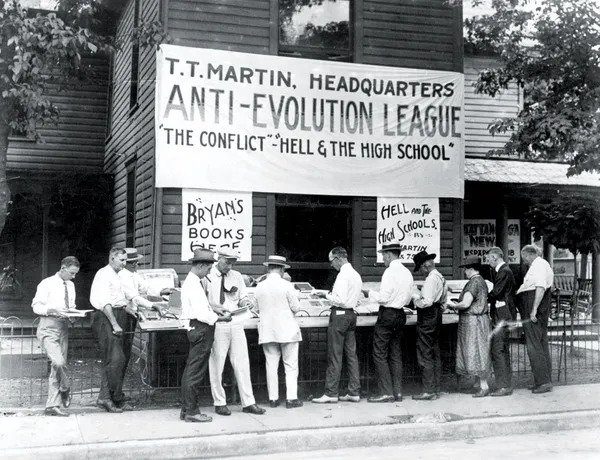

1. In which year was a Tennessee science teacher prosecuted for teaching his students about evolution?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The original kamikaze: Kublai Khan’s invasion shipwreck found?

Reading time: 4 minutes

Archaeologists from the University of the Ryukyus in Japan have discovered part of a 13th century ship that apparently belonged to Mongolian warlord Kublai Khan. The ship is believed to be a remnant of a fleet that took part in one of Kublai Khan’s failed attempts to invade Japan, in 1274 or 1281.

Popular Histories Have Influenced World Leaders, Sometimes For the Better

Reading time: 6 minutes

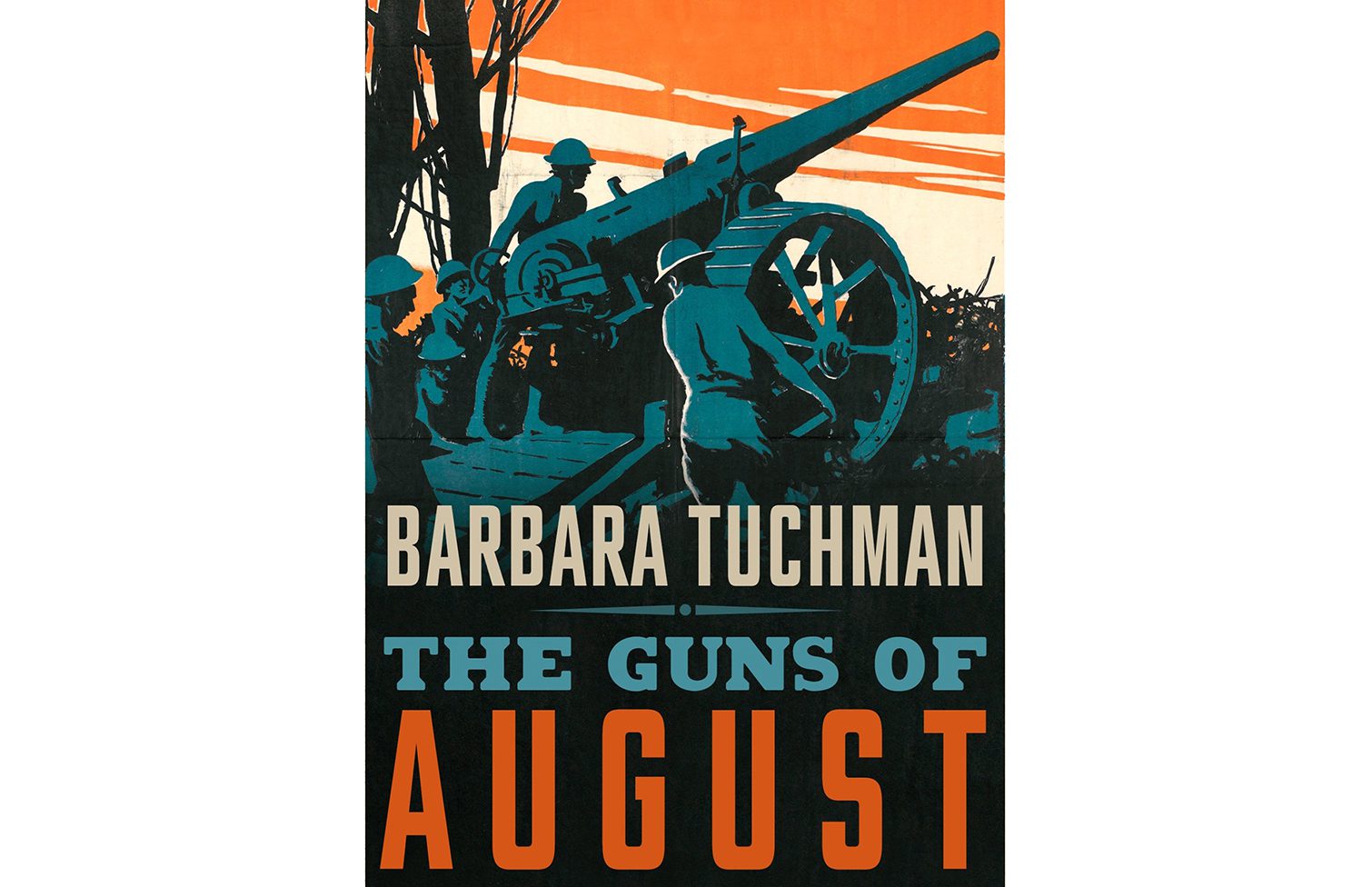

Sometimes presidents are influenced by history books. Bill Clinton consulted Balkan Ghosts: A Journey Through History by Robert Kaplan when dealing with conflicts in southeastern Europe. In 2008 Barack Obama consulted Jonathan Alter’s The Defining Moment: FDR’s Hundred Days and the Triumph of Hope for ideas about launching a strong presidency. Joe Biden liked The Soul of America: The Battle for Our Better Angels so much that he made its author, Jon Meacham, a key adviser. No historian, however, has made a more significant impact on an American president’s thoughts and actions than Barbara Tuchman. President John F. Kennedy drew important lessons from one of her books when seeking a peaceful resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.