HISTORY AT WEST POINT: TEACHING CRITICAL THINKING TO FUTURE ARMY OFFICERS

Reading time: 8 minutes

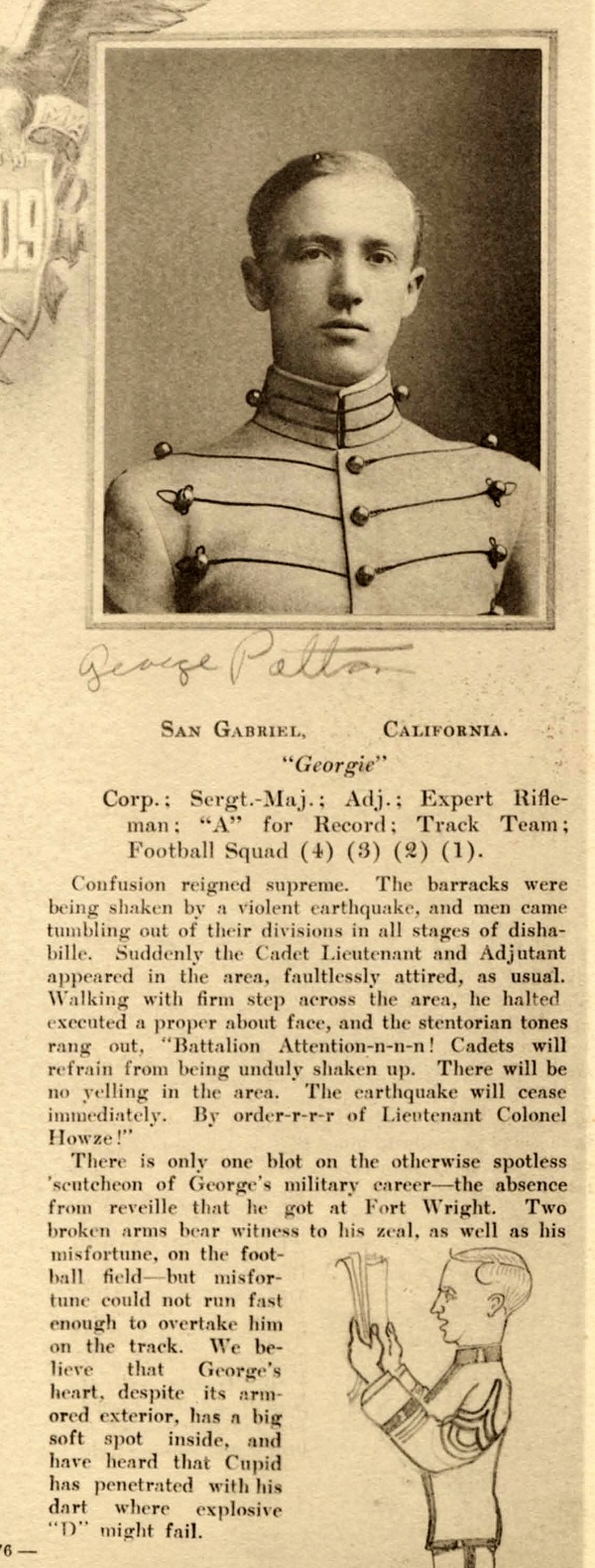

A visit to the United States Military Academy confirms that history seeps from the granite foundations of West Point itself, perched high above the Hudson River, 50 miles north of New York City. Statues of Generals Dwight D. Eisenhower, George S. Patton Jr., and Douglas MacArthur greet students every morning on the way to their first class at 0730 (that’s 7:30 a.m.). Our most successful recruiting slogan—“Much of the history we teach was made by the people we taught”—explicitly refers to history. No surprise: armies have always wrapped themselves in the glory of the past.

What might surprise many academics is the first-rate liberal education cadets receive at West Point, with a strong emphasis on history. Throughout their careers, cadets and officers receive courses from trained historians. Of course, the past provides no blueprint for the present or the future, but history provides the foundation for the critical thinking and problem solving that officers must use throughout their service.

Unlike most colleges, West Point prepares all 1,000 of each year’s graduates for the same job and the same mission: lead America’s daughters and sons in the crucible of combat. War is the most complex, demanding, dangerous, and chaotic activity undertaken by humans. Yet we entrust American soldiers to 23-year-old recent graduates of West Point and the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps. History provides army leaders one of the best laboratories for exercising critical thinking skills.

A good classroom lab requires great instructors—and lots of them. Small classes of 16 cadets and three core classes taken by all cadets translate into nearly 60 history faculty and staff for our 4,400 cadets. That large faculty means we teach no lecture classes and have no teaching assistants or adjunct faculty. Most instructors bring two or three questions to class and spend the better part of a 55-minute session leading cadets in discussion and argument, honing their critical thinking skills. Major writing assignments ensure that critical thinking skills translate onto paper as well.

As a military academy, we naturally teach military history. The History of the Military Art (called MilArt) is one of the oldest continuously taught courses in the country, dating to the mid-19th century. The course looked much different to earlier generations of cadets. When Patton completed the course in 1909, he wrote in his MilArt book, “Thank God, the last day of Art!” Eisenhower took the course in 1915, though he hated the rote memorization that then characterized it. Both men, in fact, had to memorize the location of every general at Gettysburg before visiting the battlefield.

No longer. Now, MilArt teaches critical thinking and problem solving through the discipline of history, using the latest in educational technology. This can be seen in the materials we use. West Point’s faculty has written military history for its cadets since 1817, with new texts coming every generation. The latest incarnation is The West Point History of Warfare, a million-word, 70-chapter immersive digital book enhanced with videos and interactive animated maps, widgets, timelines, and images, as well as full scholarly endnotes that incorporate hyperlinks to primary sources. Edited by our faculty and written by 50 of the best military historians in the world, it represents the finest textbook we could imagine. Introduced in the fall of 2013, The West Point History of Warfare has proved a great success in the classroom. The percentage of As in the class increased by over 50 percent, and cadets report reading more, learning more, and liking the course better. Most importantly, the technology allows cadets to come to class better prepared.

Race and gender are two of the most difficult and enduring problems in our country and our army. History can provide context and a methodology to understand the problems.

The West Point Museum also helps us teach military history. The museum has an outpost in our building that allows us to demonstrate changes in technology in the classroom. Cadets can handle the English longbow to understand how it was used on the battlefield and its role in society. We bring World War I heavy machine guns into class to understand the problems of trench warfare. Answering questions about why wars are won or lost requires understanding war, society, and tactics—not just technology. Yet hands-on learning helps us foster critical thinking.

We have two other mandatory history courses. All freshmen take an American history class. Cadets must understand the history of the nation they serve. As army second lieutenants, their uniforms, like all American soldiers’ uniforms, prominently display the letters “US” above the heart. Yet we do not teach hagiographic US history that eschews critical thinking. The US Army represents American society, for good and ill. Our cadets must learn to think critically about the past in order to deal with the complexities of the present.

The American history course features our Civil Rights Writing Program and Gender and War Writing Program. All cadets write papers based on The West Point Guide to the Civil Rights Movement, a digital reader we created with primary source text, animated maps, interactive data visualizations, videos, photos, and art. Each module of the reader supports analysis of a particular question, such as “What was more important in furthering the goals of the Civil Rights Movement, violence or nonviolence?” Other cadets in the course use The West Point Guide to Gender and War, another digital primary source reader.

We use the Civil Rights and Gender and War Writing Programs to teach historical methodologies, but also as part of the old-fashioned liberal education aim to teach character. Our mission statement at West Point states baldly that we will develop leaders of character for the nation. The Department of History contributes to the academy’s mission of character development by studying the history of race and gender to help promote empathy and understanding. Race and gender are two of the most difficult and enduring problems in our country and our army. History can provide context and a methodology to understand the problems. Our Writing Program requires cadets to evaluate evidence, understand causality, and create a narrative, while educating them about the diversity of the American experience.

In addition to the US history course, freshmen also take one of six regional history courses (East Asia, Africa, Middle East, Latin America, Europe, or Russia) linked to the language they study. History and language remain two of the best ways to understand a different culture. During cadets’ five-year service commitment, they likely will deploy somewhere far from home. Studying one culture through history combined with language helps students understand how to study any other culture. Wherever our graduates deploy, they will arrive ready to learn.

Our regional history course also has a focus on the history of gender and race. Like the nation we serve, the military has a problem with sexual harassment, sexual assault, and sexism. Nineteen-year-olds often conceive of gender as biological and fixed. History can show them that these conceptions change over time and place. An academic course can’t solve the military’s (or society’s) problems, but history, without being reductive, can provide vicarious experience to help young men and women think critically about the vital issues of gender and race.

The three core courses (military, American, and regional) provide the heart of the history curriculum at West Point for all cadets, but we also have a strong majors program. The capstone of our major is a two-semester thesis course taken by 90 percent of our 80 senior history majors. A faculty member and two or three cadets spend the year studying historiography and developing a historical question, and then each cadet writes an individual thesis using primary sources. Our best theses have won Phi Alpha Theta History Honor Society prizes.

This year, for the first time, we have a joint thesis capstone with our Computer Science and Systems Engineering Departments for a public history project. Together, cadets are developing a virtual reality app for the Normandy Battlefield. History cadets spent the summer in the archives researching and developing questions. Then they adapted the research into storyboards for the engineering cadets. With this project, engineers realize the value of history majors’ ability to think and write critically. History majors learn to use their methodologies in a multidisciplinary, high-tech team.

At West Point, we know that war will test the critical thinking skills of our cadets. The United States has seen almost perpetual conflict during my more than 30 years in uniform. I take visitors to our Memorial Room, which displays the 1,558 names of West Point graduates who have died in uniform since the War of 1812, including 99 names since 2001. On that wall are several blank panels, ready for more names. The room provides a sobering reminder that our future graduates, like our past graduates Ulysses S. Grant, John J. Pershing, and Norman Schwarzkopf, will soon be in harm’s way. As historians, we use our discipline to educate cadets so that they are ready to lead American soldiers with the wisdom that the study of history fosters.

Colonel Ty Seidule, PhD, is professor and head of the Department of History at the United States Military Academy at West Point.

The views expressed above do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the US Army, the Department of Defense, or the US government.

This article was originally published in Perspectives on History.

Articles you may also be interested in

Australian VC’s in the Mediterranean, WWII – Video

There were six Australian VC recipients during the Mediterranean and North African Campaigns of the second world war. From the heroics of Lt. Roden Cutler in Damour, Corporal Edmondson of the Desert Rats defending Tobruk in 1941 to Sgt. Kibby with his tommy-gun in El Alamein. Learn more about Australian gallantry in the Deserts of North Africa.

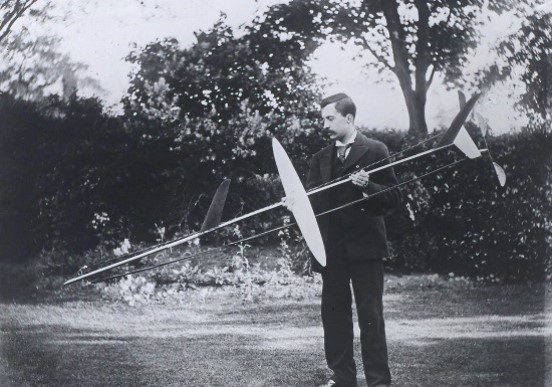

Frederick Lanchester and why quantity has a quality all of its own

Reading time: 5 minutes

Lanchester turned his mind to the subject of aerial warfare. In particular, he realised that the nature of war in the air—a novelty at the time—was fundamentally different to that of the slaughter underway on the ground below.

What happened to the French army after Dunkirk

Reading time: 5 minutes

The evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in May 1940 from Dunkirk by a flotilla of small ships has entered British folklore. Dunkirk, a new action film by director Christopher Nolan, depicts the events from land, sea and air and has revived awe for the plucky courage of those involved.

The text of this article is republished from Perspectives on History and is is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.