Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

In the annual discussion of the Gallipoli campaign Australians are subjected to a variety of hyperbole and parable as commentators and reporters offer up the same old chestnuts for want of something else to say. That at Anzac Cove ‘our nation was born’, that it ‘came of age’ or that Australian forces at Gallipoli were ‘fighting for our freedom’. Alongside this is received wisdom such as how an Englishman and a donkey somehow embodied the Australian spirit and that the Aussies could have succeeded if it wasn’t for British amateurism and tea-making.

By Mat Hardy, Deakin University.

You can debate the merit or accuracy of these legends endlessly and vehemently. However one of the clichés that always irks me is the assertion that at Gallipoli our forces were fighting against Turkey or ‘the Turks’. It is said so often that it is rarely questioned. But it is completely incorrect.

Empirical measurement

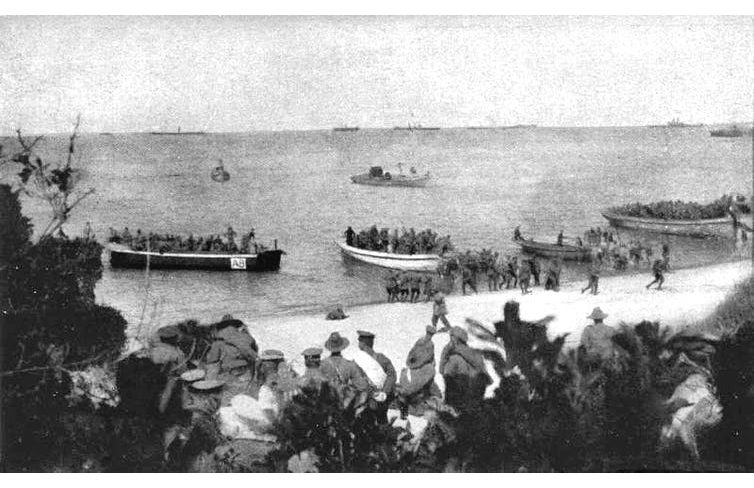

The Republic of Turkey was not declared until 1922 and was only formally recognised in 1923. Prior to that, the place we now call Turkey was the heart of the Ottoman Empire. In 1915 it was Ottoman, not Turkish soldiers that were shooting at the diggers as they hit the beaches in the darkness.

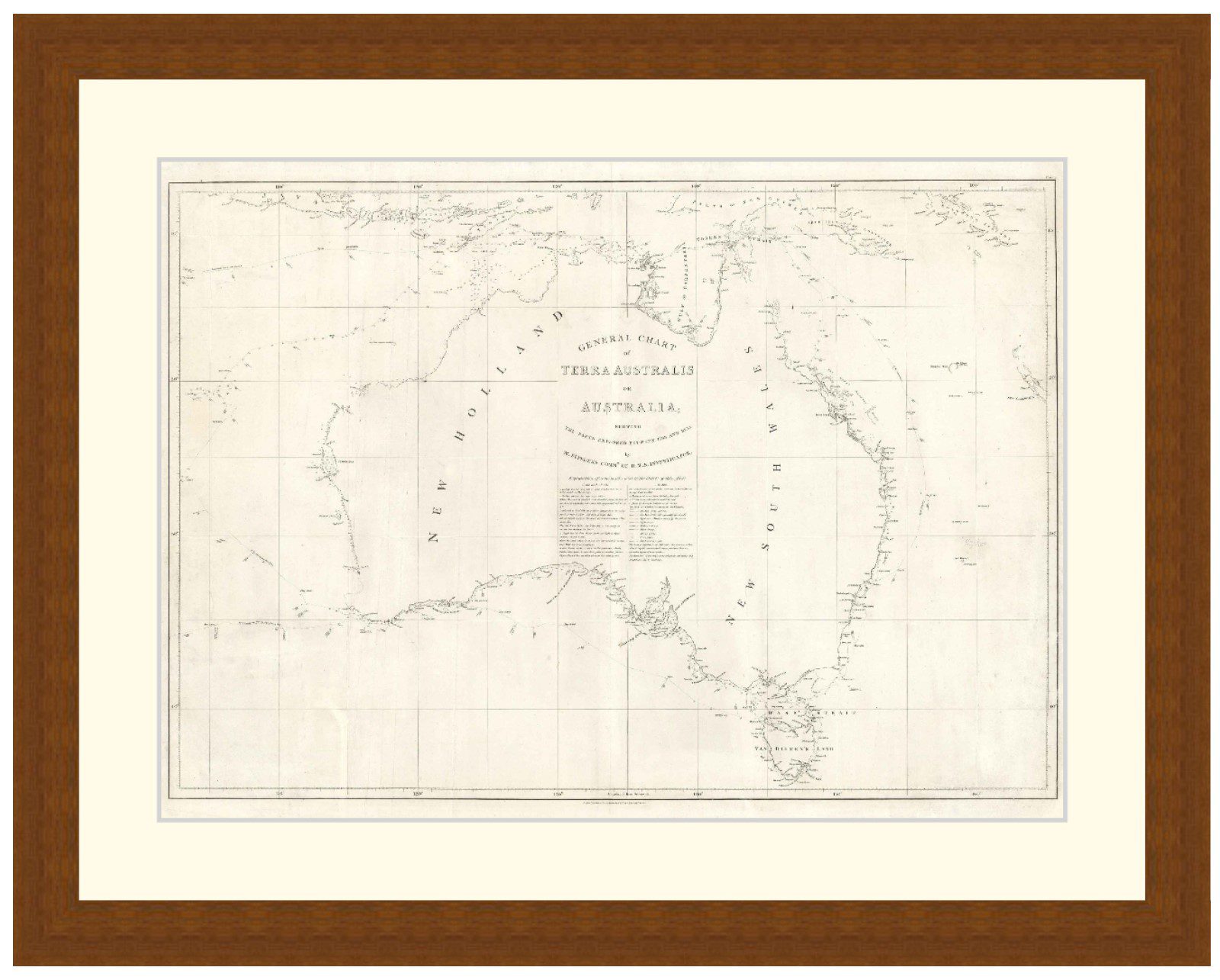

Some will try and get around this hair splitting by saying that the Ottoman Empire is synonymous with Turkish ethnicity. This is also false. Even rolled back from its medieval hey-day, the Ottoman Empire of 1915 still covered a wide patch of turf and this included huge numbers of Arabs, Armenians, Greeks and various Caucasians.

In fact without the assistance of nearly 300,000 Arabs in the ranks, the Ottoman forces would have never been able to bat on for as long as they did in the First World War. A general policy of making troops serve away from their native lands meant that plenty of the Ottoman troops in the Gallipoli campaign were not ‘Johnny Turk’ at all, but men from the Levant, Iraq and all the far-flung corners of the dying empire.

On the first day of the landings, roughly two thirds of the troops doggedly defending the heights were Arabs, mainly from Syria. They and their like served throughout the war, usually unwillingly. For the Arabs, there was no great love of their Ottoman masters. Many of these conscripts were little more than slave coffles of untrained cannon fodder. But for Mustafa Kemal (Attatürk), their sacrifice formed the first vital step of his military reputation.

Ironically it was the long-term spurning of non-Turks within the empire that sowed the seeds of revolt and provided the British with the handy tool of asymmetric warfare.

And just as Australia has a great deal of national identity invested in Gallipoli, so do the Arabs place a lot of stock in their role fighting against the Ottomans.

Sorrows of Arabia

The Arab Revolt and their use as a guerrilla force against the over-extended supply lines of the Ottomans makes for a good film. This was the point where the noble desert warriors rose up to be a nation again and were to be rewarded with self-determination at the conclusion of the war.

Naturally it didn’t quite pan out that way. The numbers actively involved in the revolt were a fraction of those serving on the other side and the rebels were often from regions where the Ottomans had very little control anyway. But like the heavy emphasis Australians have placed on Anzac Cove, there has been a disproportionate weight placed by the Arabs upon their uprising.

Not that it did most of them much good. After the war, the British and French did as they pleased. The Cairo Conference of 1921

saw Churchill and his ‘Forty Thieves’ parcel out the rewards to some favourites and make up some borders, stamping a political geography on the whole Middle East that still persists today. Only two Arabs were invited. Favourites like Faisal and Abdullah were given puppet kingdoms, setting the scene for decades of squabbling and the eventual rise of nationalists like Saddam Hussein and Hafez al-Assad a generation later.

So whatever you think about the idea that Australia was ‘forged’ at Gallipoli, the fact remains that many other nations were, much more literally, born from the ashes of the campaign to solve the Eastern Question.

Including Turkey.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Articles you may also like

In their own words: letters from ANZACs during the Gallipoli evacuation

Just five days before Christmas, in the early hours of Monday December 20, 1915, the last Anzac troops left Gallipoli in what Australian historian Joan Beaumont called an “elaborate game of deception”. Self-firing guns were rigged to take pot-shots and camp fires lit to give the impression of there being more soldiers than there were. The Australians […]

Battle of 42nd Street – Anzacs Proving Germany Could be Beaten

Morale can make all the difference on the battlefield. On the 27th May 1941, with the Greek island of Crete close to loss and the Allies in full retreat, a 12 minute moment of madness by Australian and New Zealand troops proved that aggression and bravery could overcome Germany’s elite troops. By Richard Shrubb. Background […]

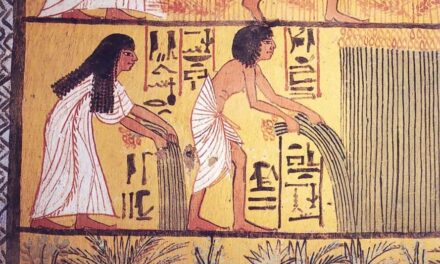

Prehistoric female hunter discovery upends gender role assumptions

Researchers have generally thought that only prehistoric males hunted, however a recent publication in Science Advances disputes this notion. Big-game hunting is an overwhelmingly male-biased behavior among recent hunter-gatherer societies. Such observations would seem to suggest that this gendered behavioral pattern is an ancestral one, ostensibly stemming from life history traits related to pregnancy and […]

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.