Reading time: 5 minutes

France to the west, Russia to the east; Germany had a strategic plan to prevent full-scale war in the early 20th century. So why did it fail?

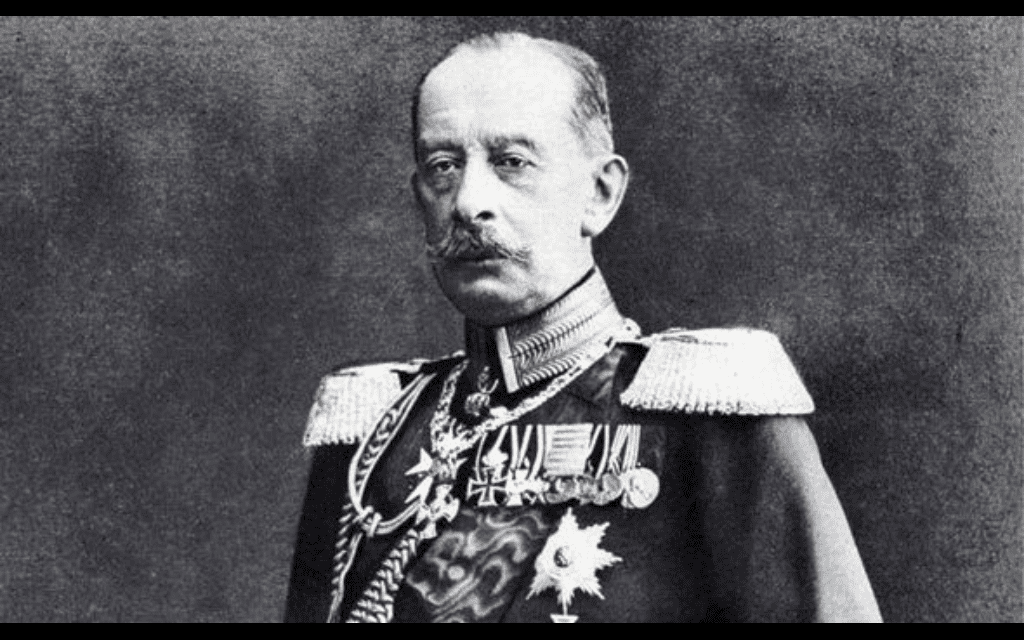

Schlieffen’s idea was perfected in the winter of 1905 when, as a result of the Russo-Japanese war, Russia was eliminated as a serious threat to the European status quo for the foreseeable future. It would first of all have to recover from a lost war and from revolution. For those in Germany and Austria-Hungary who feared Russia and its ally France as potential future enemies, this was a perfect time to consider ‘preventive war’.

By Annika Mombauer, The Open University

Such a war aimed to unleash a war while Russia was still weak. In the not too distant future, Germany’s military planners predicted, Russia would become invincible. This was a fear shared by other governments, but in Britain and France it had led to the decision to seek friendlier relations with Russia.

The new Entente between Britain and France was only just being shown to be effective following the First Moroccan Crisis. As a result of the Crisis Germany began to feel the full effects of her own expansionist foreign policy. To Germany, British involvement in a future war now seemed almost certain.

One consequence would be that Italy, allied to Germany and Austria since 1882, would become a less reliable ally. In a war involving Britain, Italy would be unable to defend its long coastlines and might therefore opt to stay neutral in a future war.

The international events of 1905-06 marked the beginning of Germany’s perceived ‘encirclement’ by alliances of possible future enemies against her. Between this time and the outbreak of war in 1914, the General Staff became more concerned about the increasing military strength of Germany’s enemies.

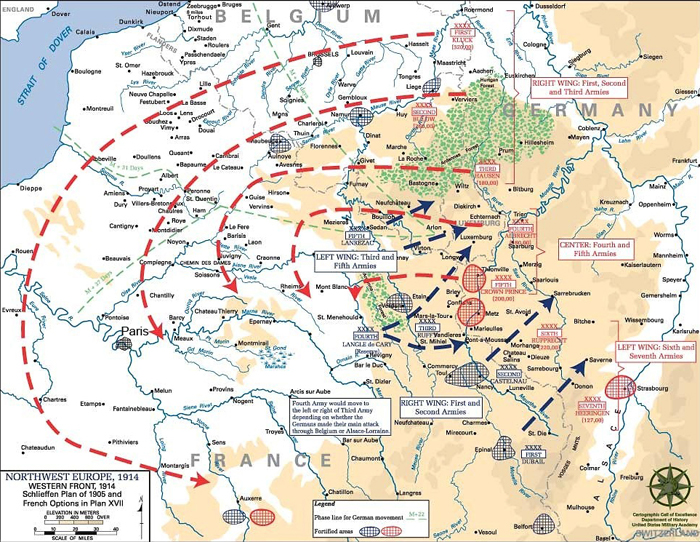

Schlieffen saw Germany’s best chance of victory in a swift offensive in the West, against France, while in the East, the German army was initially to be on the defensive. Russia would be dealt with after France had been delivered a decisive blow. In effect, Schlieffen aimed to turn the inescapable reality that Germany would have to fight a two-front war into two one-front wars which it could hope to win. But for the plan to succeed, Germany would have to attack France in such a way as to avoid the heavy fortifications along the Franco-German border.

The logistics of the plan and its significance for the German war effort

Prior to World War I, The Schlieffen Plan established that, in case of the outbreak of war, Germany would attack France first and then Russia.

Instead of a ‘head-on’ engagement, which would lead to position warfare of inestimable length, the opponent should be enveloped and its armies attacked on the flanks and rear.

Moving through Switzerland’s mountainous terrain would have been impractical, whereas in the North, Luxembourg had no army at all, and the weak Belgian army was expected to retreat to its fortifications.

Schlieffen decided to concentrate all German effort on the right wing of the German army, even if the French decided on offensive action along another part of the long common border and even at the risk of allowing the French temporarily to reclaim Alsace-Lorraine.

In his planning, Schlieffen counted on two things: that German victory in the West would be quick (he estimated this to take about 6 weeks), and that Russian mobilisation would be slow, so that a small German defensive force would suffice to hold back Russia (considered to be a ‘clay-footed colossus’) until France was beaten.

After a swift victory in the West, the full force of the German army would be directed eastwards. Russia would be beaten in turn. This was the recipe for victory, the certain way out of Germany’s encirclement.

The plan was first put to paper at the end of 1905 when Schlieffen retired, and was adapted to changing international circumstances by his successor, the younger Helmuth von Moltke.

The underlying principle remained the same until August 1914. By the autumn of 1913, all alternative plans had been abandoned, so that Germany would have to begin a European war, whatever its cause, by marching into the territories of its neutral neighbours in the West.

Shortcomings of the plan: Why didn’t the Schlieffen Plan work?

There were a number of shortcomings associated with the plan. It imposed severe restrictions on the possibility of finding a diplomatic solution to the July Crisis, because of its narrow time-frame for the initial deployment of troops.

The escalation of the crisis to full-scale war was in no small measure due to Germany’s war plans. But more importantly, it unleashed the war with Germany’s invasion of neutral countries to the West.

The violation of Belgian neutrality in particular proved to Germany’s enemies that they were fighting an aggressive and ruthless enemy. It provided the perfect propaganda vehicle for rallying the country behind an unprecedented war effort and sustained the will to fight for four long years of war.

And it provided ample proof, if proof were needed, for the victors to allocate responsibility for the outbreak of the war to Germany and its allies.

This article was originally published by The Open University.

Podcasts about the Schliffen Plan

Articles you may also like

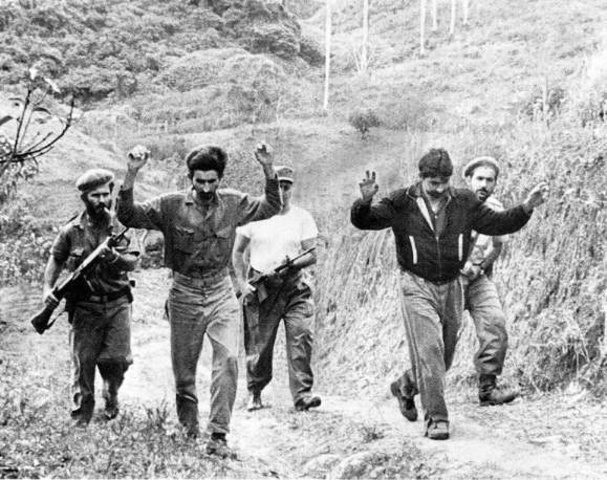

Hubris and Miscalculation: The failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion

HUBRIS AND MISCALCULATION: THE FAILURE OF THE BAY OF PIGS INVASION By Michael Vecchio The threat of Nazi villainy had been defeated, however another authoritarian threat rapidly placed over half of Europe behind what Winston Churchill called an “Iron Curtain”. The Soviet Union’s aggressive brand of Communism startled much of the Western world, but perhaps […]

Weekly History Quiz No.290

1. How many ships did the Battleship Bismarck sink?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article is republished from The Open University and is is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.