Reading time: 5 minutes

It’s our experience that most people think archaeology mainly means digging in the dirt.

Admit to strangers that you are of the archaeological persuasion, and the follow-up question is invariably “what’s the best thing you’ve found?”.

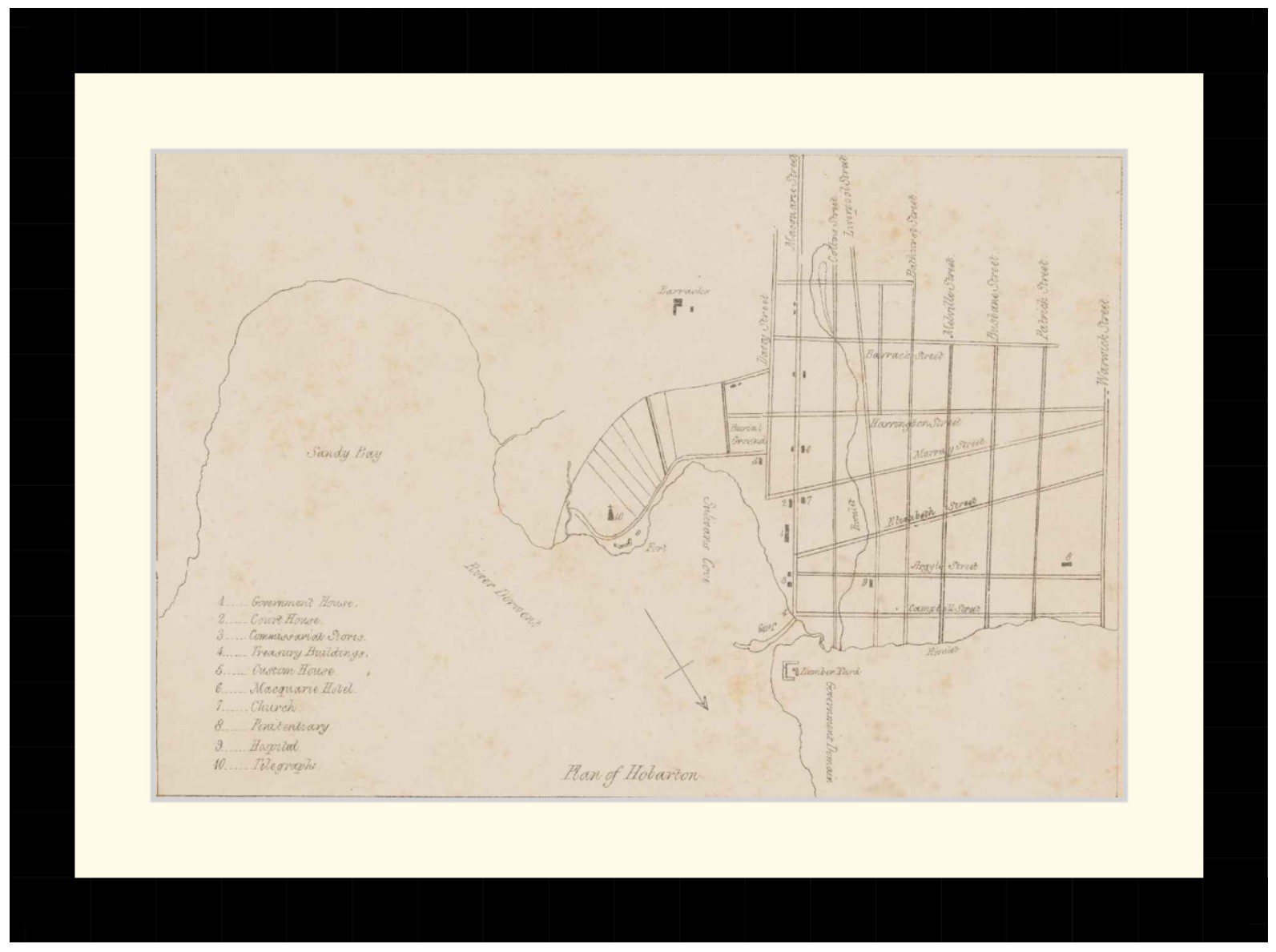

Start to tell them about a fantastic ink and watercolour plan you unearthed in library archives, or an old work site you stumbled upon in thick eucalypt bush, and their eyes glaze over.

By Richard Tuffin and Martin GIbbs, University of New England.

People invariably want to hear about skeletons, pots and bits of shiny metal. It’s this type of stuff that you will often see in the media, giving the misleading impression that archaeological process is only about excavation.

While the trowel and spade are an important inclusion in the archaeological toolkit, our core disciplinary definition – that of using humanity’s material remains to understand our history – means that we utilise many ways of engaging with this past.

Read more: Poor health in Aboriginal children after European colonisation revealed in their skeletal remains

A hole in the ground

Of course, there’s nothing like a tidy hole in the ground to get people’s attention. Yet what often gets lost in the spotlight’s glow is that excavation is the last resort; it’s the end result of exhaustive research, planning and design.

In the research environment, excavations are triggered by having no, or only a low level of, other streams of evidence.

This similarly applies in mitigating the impacts of development, where the threat of an historical site’s partial or complete removal adds an element of evidence recovery.

Should the excavation be ill-thought out, or divorced from proper research goals, the results – and therefore the net benefit of the whole exercise – are lessened, if not completely lost.

This is particularly so for historical archaeologists, where the availability of documentary archives, oral testimony and the remaining landscape itself can reveal so much – before trowels meet dirt.

Lots of work before digging

For the historical archaeologist, a huge amount of work must take place before an excavation can even be planned, with invasive investigations sometimes not even considered.

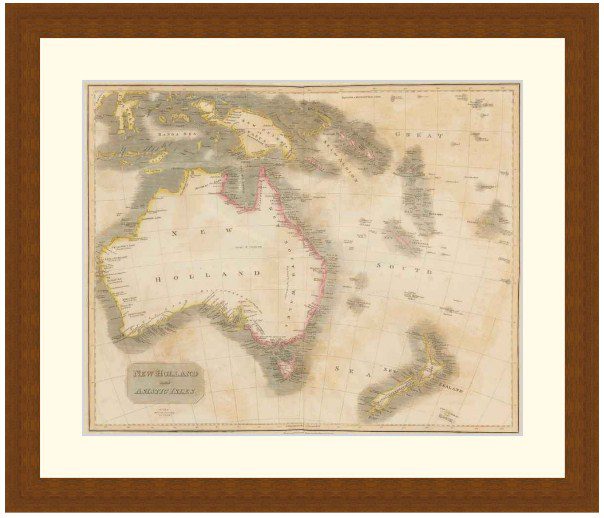

In our particular field, the historical archaeology of Australia’s convict system (1788-1868), there is a vast amount of documentary evidence that requires interrogation before any archaeological process can begin.

As an example, in the Tasmanian Archives and Heritage Office, 35 metres of shelf space is taken up just by the official correspondence records for the period 1824-36.

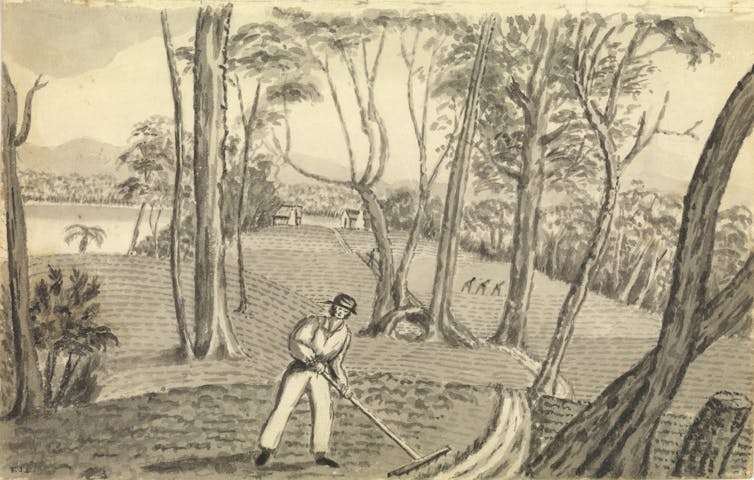

Correspondence, reports, tables, diaries, newspapers, maps, plans, illustrations and photographs contain a wealth of information about the convict past. These can be used to query how people interacted with each other and the places, spaces and things that were created and modified as a result.

The experience of convict labour

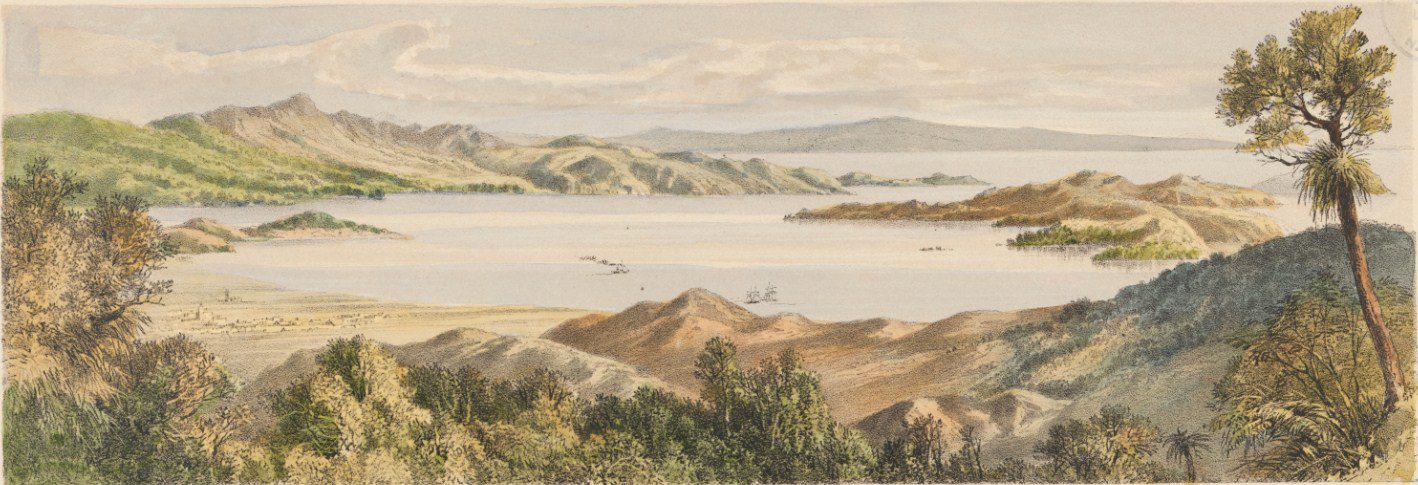

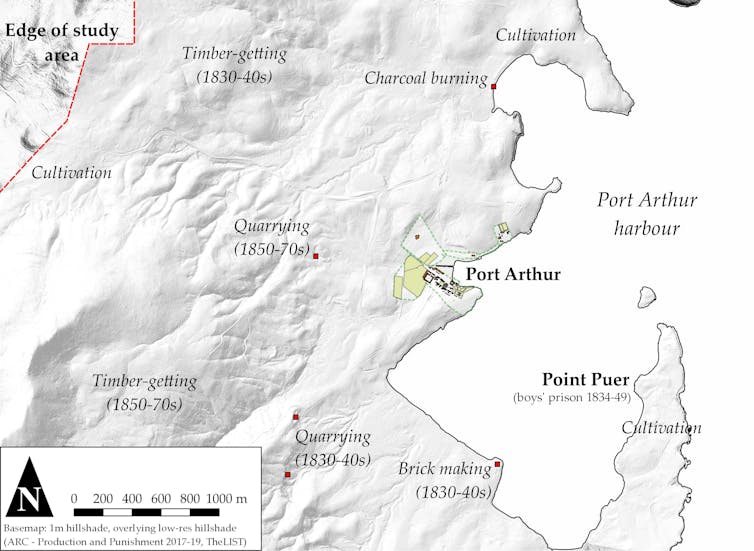

We are currently over a year into a research project (called Landscapes of Production and Punishment) that uses evidence of the built and natural landscape to understand the experience of convict labour on the Tasman Peninsula, Tasmania (1830-77).

At its peak, nearly 4,000 convicts and free people lived on the penal peninsula. Their day-to-day activities left traces in today’s landscape that we locate and analyse using historical research, remote sensing and archaeological field survey.

LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging, a form of 3D mapping) has been used to great effect, mapping large areas in high detail, which have then been surveyed to find the sites of convict labour. These include quarries, sawpits, charcoal-burning stands, brick pits, tramways, roads and paths, cultivated fields and boundaries.

No soil was disturbed

Without turning a sod, we have recreated historic landscapes that have long lain dormant.

These have then been brought to life through the records of the system, which were historically used to account for the convicts and their labour. These include records about the lives of convicts whilst under sentence, as well as statistics on the products and processes of their labour.

This raw data shows us the outputs of industrial operations carried out by the convicts, like brick making, sandstone quarrying, lime burning and timber-getting, as well as the manufactories that produced leather, timber and metalwork goods by the thousand.

The records also locate convict and free settlers back into time and space, reconnecting them to the places and products of their labour.

As the project develops, excavation may be one of the archaeological methods used to retrieve our evidence – but only once we have exhausted all other avenues of enquiry.

Controlled destruction

As archaeologists, we have a responsibility to ensure that the controlled process of destruction that is an archaeological investigation has the greatest possible research return.

Without this due process, our work becomes unhinged from research frameworks. The excavations devolve into expensive and directionless treasure hunts from which little research value can be extracted.

The archaeologist’s profession – be it as an academic or working in the commercial and government sector – is more than excavation. It encompasses a diverse range of skills and techniques which can be deployed to aid in our central task of understanding the lives of those who came before.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about archaeology

Articles you may also like:

The Bloody Beachheads: The Battles Of Gona, Buna And Sanananda – One Day Conference

The Battle of the Beachheads was the bloodiest of all the Papuan campaigns. The resolve and tenacity of the Japanese defenders was, to Allied perceptions, unprecedented to the point of being “fanatical”, and had not previously been encountered. Please join a group of well-qualified speakers as we examine the Battle of the Beachheads in a one-day conference.

What was The Schlieffen Plan?

Reading time: 4 minutes

France to the west, Russia to the east; Germany had a strategic plan to prevent full-scale war in the early 20th century. So why did it fail?

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.