Reading time: 5 minutes

Over 80 years ago Australians dressed in steel helmets and khaki shorts, and often not much else, sat in weapon pits in the Egyptian sun about 120 kilometres west of Alexandria. They were preparing for what history would call the second battle of El Alamein, the great offensive planned by Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery. In the summer heat of July 1942, his predecessor, Archibald Wavell, had held the German–Italian drive towards Egypt, a battle in which the 9th Australian Division had played a notable part. Now, after gathering more troops, tanks and guns, Montgomery was ready to launch his Eighth Army against General Erwin Rommel’s Panzer Armée Afrika, a commander and a force admired and respected even by their adversaries.

If it succeeded, Montgomery’s assault might reverse the fortunes of Allied armies in North Africa and the Mediterranean. So far, after victories early in 1941 against the Italians in Eritrea and in Libya, when tens of thousands of demoralised Italians had been captured, no British general had been able to gain a decisive success in the theatre. In 1941, Greece and Crete had been lost. In north Africa, Tobruk had been saved, but in tank battles in Libya Rommel had demonstrated his skill. A British Commonwealth advance to Gazala had ended in disaster and the loss of Tobruk had pushed Axis forces to within striking distance of Alexandria. Allied morale had plummeted and the troops were convinced that they could not beat Rommel. But after a three-week fight on a line between the railway halt of El Alamein and the lip of the impassable Qattara Depression, the Eighth Army had held. Now, under yet another commander, it faced the task of once again taking on Rommel’s Panzer Armée.

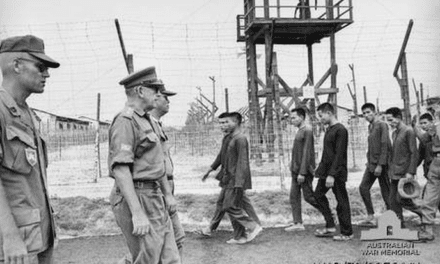

Australians at home knew about this epic desert war, a contest so different to the war that was occupying headlines and newsreels. But for the past 10 months, since the Japanese had entered the world war so spectacularly by attacking Pearl Harbor and the European colonies in Asia, the war in what they called the Far East had dominated Australia’s attention. An entire Australian division, the 8th, had been swept into captivity by the Japanese victories in Malaya, Singapore and the islands to Australia’s north. Winston Churchill had sent two of Australia’s three divisions back from the Middle East, falling out with Prime Minister John Curtin over where they should be deployed. Australia’s north had been bombed and Japanese submarines had penetrated Sydney Harbour. While the 9th Division faced Rommel’s panzers at Tel el Eisa in July, Australian Militia had been driven back over the Owen Stanleys towards Port Moresby. While Montgomery gathered strength and planned his great counter-stroke, Australian troops had held the Japanese on the Kokoda Trail and begun the painful advance northwards. The war against Japan captured Australia’s attention, and (judging by the number of books published since) that preoccupation has never wavered.

But late in October 1942, men of the 9th Division, the only remaining Australian troops in the Mediterranean theatre, prepared for their next test. After a colossal bombardment, Montgomery’s infantry—Australian, Scottish, New Zealand, Indian and British—crossed the start-line on the evening of 23 October. The Australians’ task was to ‘pin’ the German defenders of the vital coastal sector while the infantry further south opened up a route for British armour to break through the belts of mines protecting the Axis line. The battle was a vicious 12-day fight in which (measured by their disproportionate casualties, including 500 dead) Australians played a vital part. By early November, Rommel’s troops at last began a retreat westwards that ended six months later with the capitulation of Axis forces in Africa. As Rommel ordered the withdrawal, Australian troops entered the Papuan village that would give its name to the Kokoda campaign, which in retrospect became the focus of Australia’s understanding of World War II.

The victory at El Alamein represented perhaps the British Commonwealth’s finest moment. An army of divisions from Britain and all major dominions (except Canada) had defeated an Axis army in the field. Admittedly, Montgomery had enjoyed a substantial material superiority to Rommel, but the victory was sufficient. Montgomery had won the first of the great Allied victories, one justifying Churchill’s later pronouncement (rightly qualified with ‘it might almost be said’) that before Alamein the Allies had never had a victory and after it had never had a defeat.

For the men of the 9th Division, Alamein was their last experience of war against the Germans and Italians. They were sent home, in response to urgent appeals from Douglas MacArthur and John Curtin. From early 1943, the only Australians to prosecute the war in Europe were airmen of the RAAF and sailors of the RAN, now all but forgotten. The jungle war against Japan came to dominate Australia’s memory of World War II.

This lopsided remembrance is unfortunate. However much Australians rightly recall the war on their doorstep, in Singapore, the islands and Papua New Guinea, the Australian contribution to the struggle against Nazi Germany and fascist Italy was significant on a world stage. Fifty years ago, Bernard Montgomery (by then Montgomery of Alamein) travelled to Egypt on what proved to be his last overseas trip (though he lived for another 10 years, dying at 88). After he visited the war cemetery at Alamein, with its 7,350 graves and memorial bearing 11,945 names, his companion, a former staff officer, noticed he was subdued. ‘I’ve been thinking of all those dead’, he confessed. His thoughts turned to the many Australian headstones he had seen that day. ‘The more I think of it’, he said, ‘the more I realise that winning was only made possible by the bravery of the 9th Australian Division’.

In a few weeks we will of course see articles marking the 75th anniversary of the end of the Kokoda campaign. It is fitting to recall that Australian troops helped to defeat Nazi Germany, as well as liberating Australian Papua.

This article was originally published in The Strategist.

Podcasts about El Alamein:

Articles you may also like:

Weekly History Quiz No.225

1. Which group was the main challenge to Greek power in the Eastern Mediterranean in the Greek golden age?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article is republished from The Strategist under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License in accordance with their republishing policy.