Reading time: 5 minutes

1915 was a critical year for Australians, and not just because of the pride and myth-making associated with Gallipoli. Today we struggle to capture a sense of the profound shock and anxiety the landing at Anzac Cove brought to Australia. But it was this, together with a wider understanding that the war was not going well, that defined 1915 and drew Australians ever deeper into the vortex of total war.

Before Gallipoli, Australians had been watching the war closely. They were especially aware of the scale of the fighting and the toll in lives it was taking on the European battlefields. While the reported success of the landings at Anzac was indeed the cue for some warm self-congratulation in Australia, it was also the cue for excruciating anxiety and fear surrounding the wellbeing of loved ones.

By Bart Ziino, Deakin University

Families clearly struggled with their feelings as they waited anxiously for news of loved ones. “We are passing thro’ a time of terrible anxiety just now,” wrote Margaret Melvin,

and it is you dear son who is ever in our minds, our hearts and prayers. We do not know where you are nor how you are … It is very hard writing to night, but of course we keep hoping and trusting all is well with you, our dear, dear son.

A strained Bertha Monash told her father that she simply hoped to “wake up and find this all a bad dream”.

In 1915, that sudden immersion into deep anxiety came in the context of a war not going well for the allies, and renewed moral outrage at the German sinking of the passenger liner Lusitania, and their use of poison gas on the western front. The result was not a recoiling from the war, but an even greater commitment to it. This was the logic of total war, in its insistence on the ordering of all of the nation’s resources, military, industrial, and psychological in the effort to defeat the enemy.

‘Get busy and do things’

In particular, the experience of 1915 had a marked effect on Australians’ psychological and emotional commitment to winning the war.

It was not the excitement but the seriousness of the war that drove men to the recruiting stations, and inspired others to donate to the patriotic funds. Others still – mostly women – expressed their determination by mobilising their own labour as they produced “comforts” for the men at the front, and increasingly for those wounded and hospitalised.

This reality suggests Australians understood much more about the war than we might give them credit for, despite being so far from the front. The casualty lists told of the scale of the war in ways that journalists’ accounts did not; letters from the front spoke of the horrors of battle, despite the presence of the censor.

From the middle of 1915, the wounded began to return with stories to tell and evidence of the war on their bodies. One Melbourne woman was struck at the awful sight of the war come home: “the returned wounded give one the creeps – they all look so thin and worn out”.

Still, knowledge of the war affirmed for those at home the necessity of fighting.

Thousands of Australians had already died in its name; the barbarity of the enemy was popularly confirmed; and the Empire itself seemed threatened. The urge to be “get busy and do things” was built on such feelings, and it showed that determination to win the war was not necessarily a question of blind patriotism.

Australians felt it much more as a question of resignation to a war they deemed righteous. One Sydney man explained the burden Australians had willingly assumed:

Without doubt this dreadful War is turning everything upside down but of course it has to be fought to a finish and everything else has to take a second place.

These were the attitudes that would help to sustain the war on all sides.

Over the course of 1915 the war continued to expand and take on a life of its own. This too was accepted, though with the anxious observation that it was growing out of control. Margaret Stanley, wife of the Victorian Governor, likened the war to “the spreading of some horrible and hideous disease”.

It was in this environment that ultimate failure at Gallipoli could be met with a muted response. The war had not been foreshortened by the risky adventure, but in any case Australians had come to understand that the war would not end suddenly. They were ready now for a long war.

In accepting the long war, Australians were reflecting what was happening across the belligerent societies, as the war developed a logic and a power of its own. The path to total war in Australia would in one sense be thwarted by the failure to introduce conscription the following year. In another sense it had already achieved its fatal grasp on the minds of those who saw themselves intimately and personally invested in its outcome, whether they liked it or not.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about Gallipoli 1915

Articles you may also like

D-Day succeeded thanks to an ingenious design called the Mulberry Harbours

Reading time: 4 minutes

When Allied troops stormed the beaches at Normandy, France on June 6, 1944 – a bold invasion of Nazi-held territory that helped tip the balance of World War II – they were using a remarkable and entirely untested technology: artificial ports.

To stage what was then the largest seaborne assault in history, the American, British and Canadian armies needed to get at least 150,000 soldiers, military personnel and all their equipment ashore on day one of the invasion.

General History Quiz 169

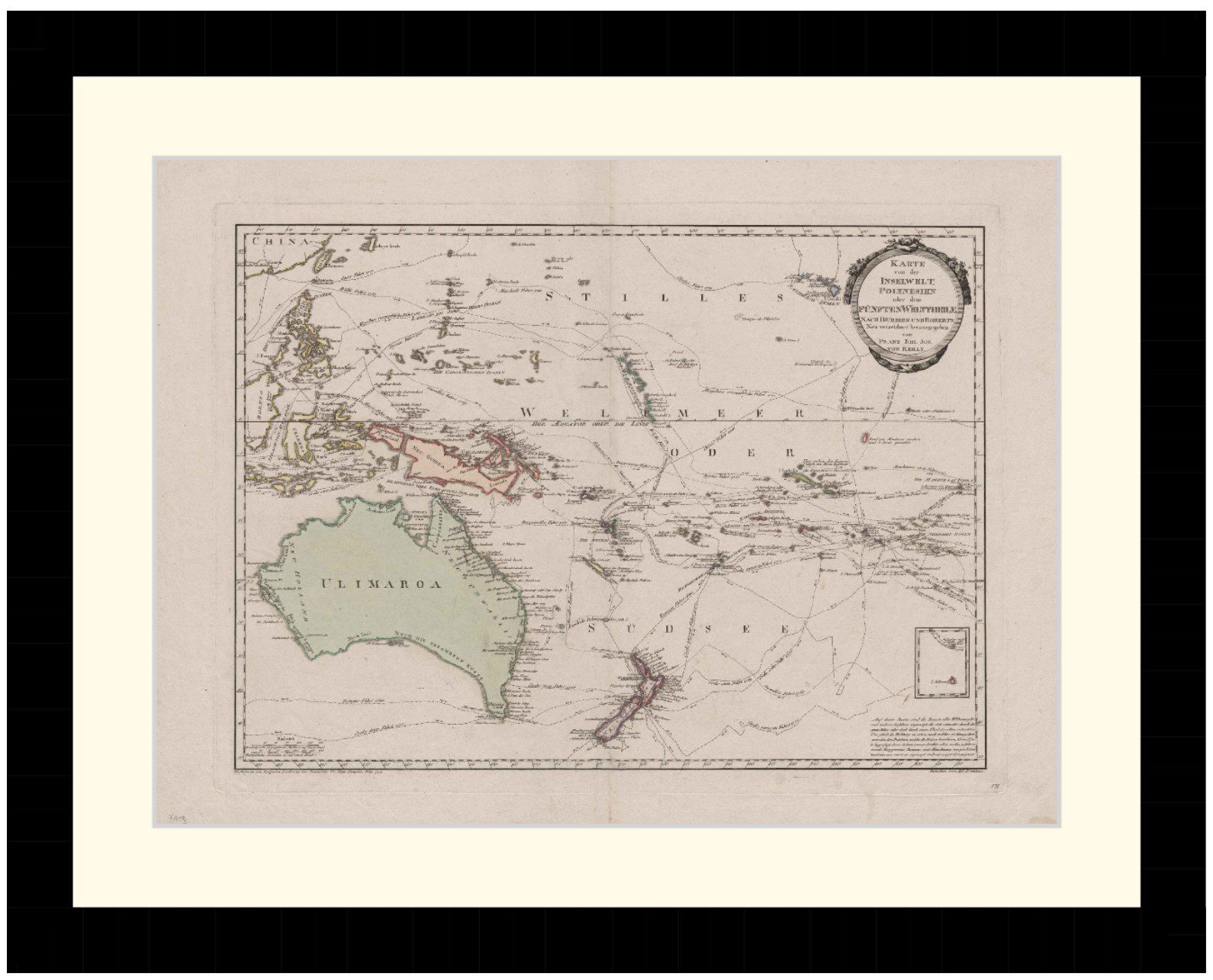

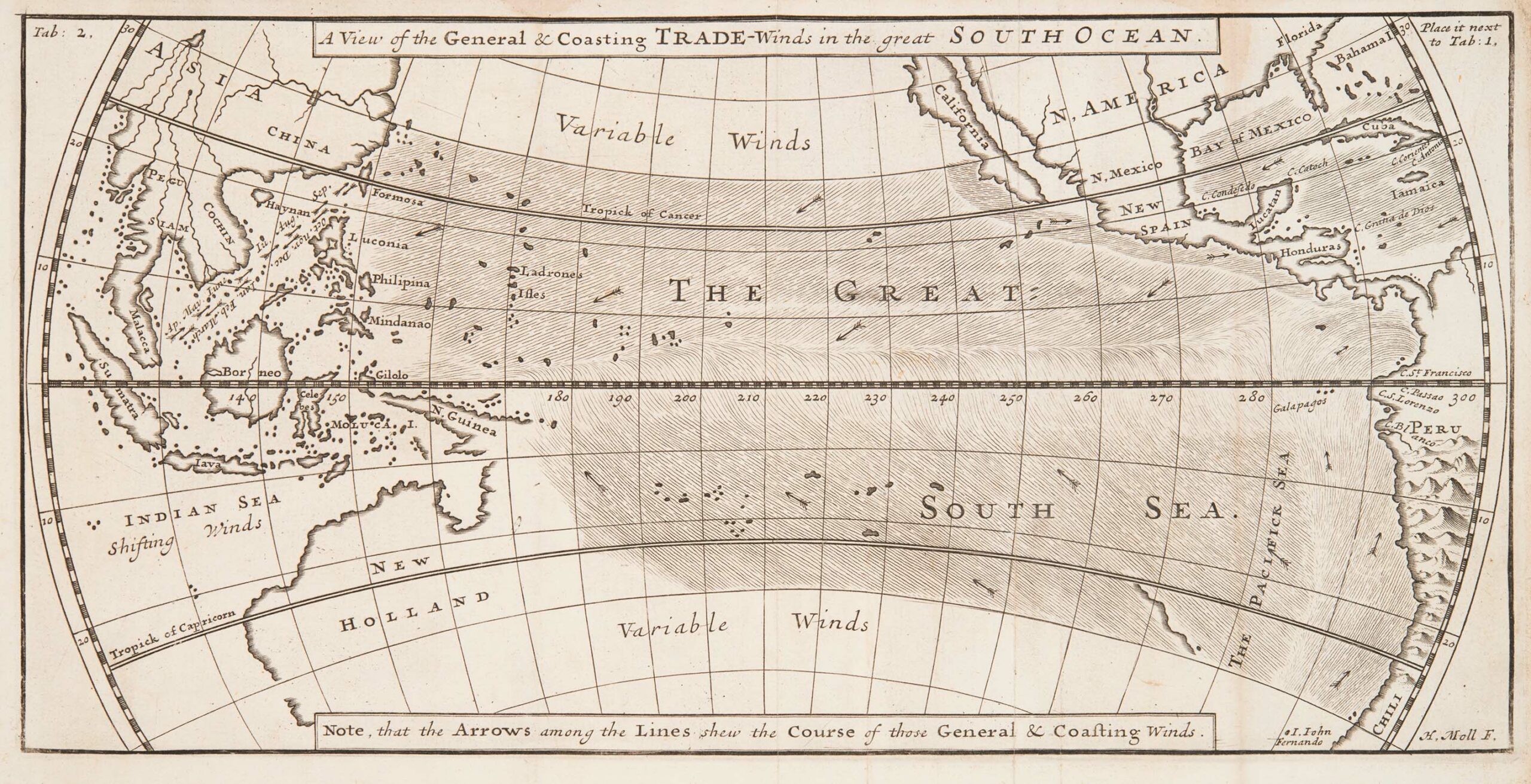

1. Which European power controlled the Manila Galleon trade across the Pacific ocean in the 1600s?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The Art of War – Audiobook

The Art of War is a Chinese military treatise written during the 6th century BC by Sun Tzu. Composed of 13 chapters, each of which is devoted to one aspect of warfare, it has long been praised as the definitive work on military strategy and tactics of its time. The Art of War is one of the oldest and most famous studies of strategy and has had a huge influence on both military planning and beyond.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.