Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

From the cave paintings of Montignac to the Mercator Projection and beyond, maps explain how humans viewed the world throughout history.

By Madison Moulton

Thousands of years before satellites and GPS, the humble map was used to make sense of the world. These prized possessions allowed humans to navigate, facilitate trade, conquer foreign lands, and shape geographical narratives of power and influence. Behind those maps were history’s greatest cartographers, who developed mathematical methods to advance one of the world’s most important tools. From scrolls to smartphones, the history of cartography provides a timeline of how humans understood the world over the centuries.

The World’s First Maps

There is no clear winner of the title of world’s earliest map. Some historians argue the first map dates back to 25 000 BCE – a mammoth tusk with markings that some archaeologists believe depict the landscape of the area in which it was discovered. Others have connected rock art paintings in France with constellations, arguing these depictions from 17 000 BCE are the earliest known star maps. But credit for the first surviving map of the ‘entire’ world goes to the Babylonians.

In 600 BCE, the Babylonians produced a ‘world map’ with Babylon at the centre, surrounded by nearby regions and an expansive ocean. The map is a symbolic representation of how the Babylonians saw the world – not a realistic one – as areas known to the Babylonians at the time were deliberately omitted. Around the same time, several world maps emerged from Greece thanks to major scientific advances, but they were often based on speculation and had no measure of scale.

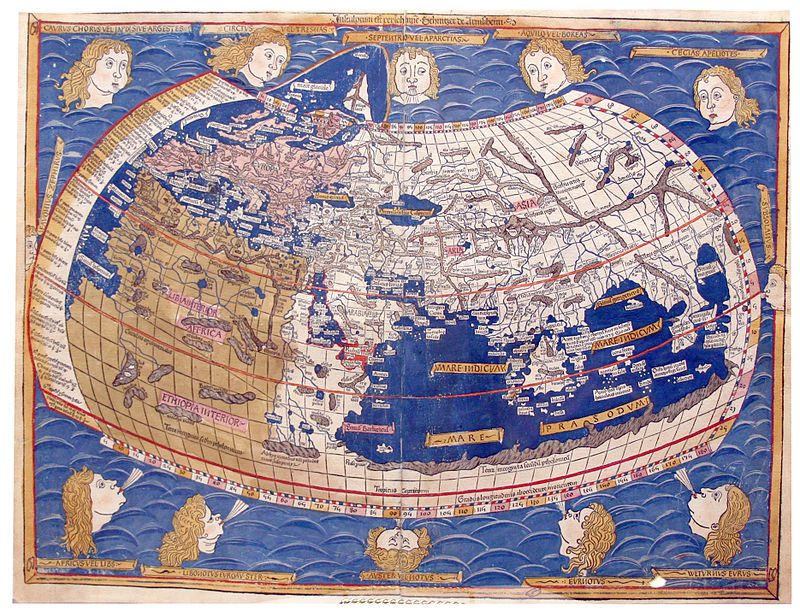

The true birth of cartography – the study of mapmaking – is commonly credited to Claudius Ptolemy. In his work Geographia, written in the second century CE, Ptolemy revolutionized geography and cartography. He outlined a coordinate system of latitude and longitude for accurate navigation, mapped thousands of areas with their corresponding coordinates, and was the first to use perspective projection to display the globe effectively on a two-dimensional surface.

Advances through the Middle Ages

Following the fall of the Roman Empire, advances in cartography were largely halted until years later when Muslim scholars and travellers developed the study further. In the 9th century, Abbasid caliph al-Ma’mun commissioned geographers to remeasure the scale and distances used to calculate maps, leading to the first accurate calculation of the circumference of the earth.

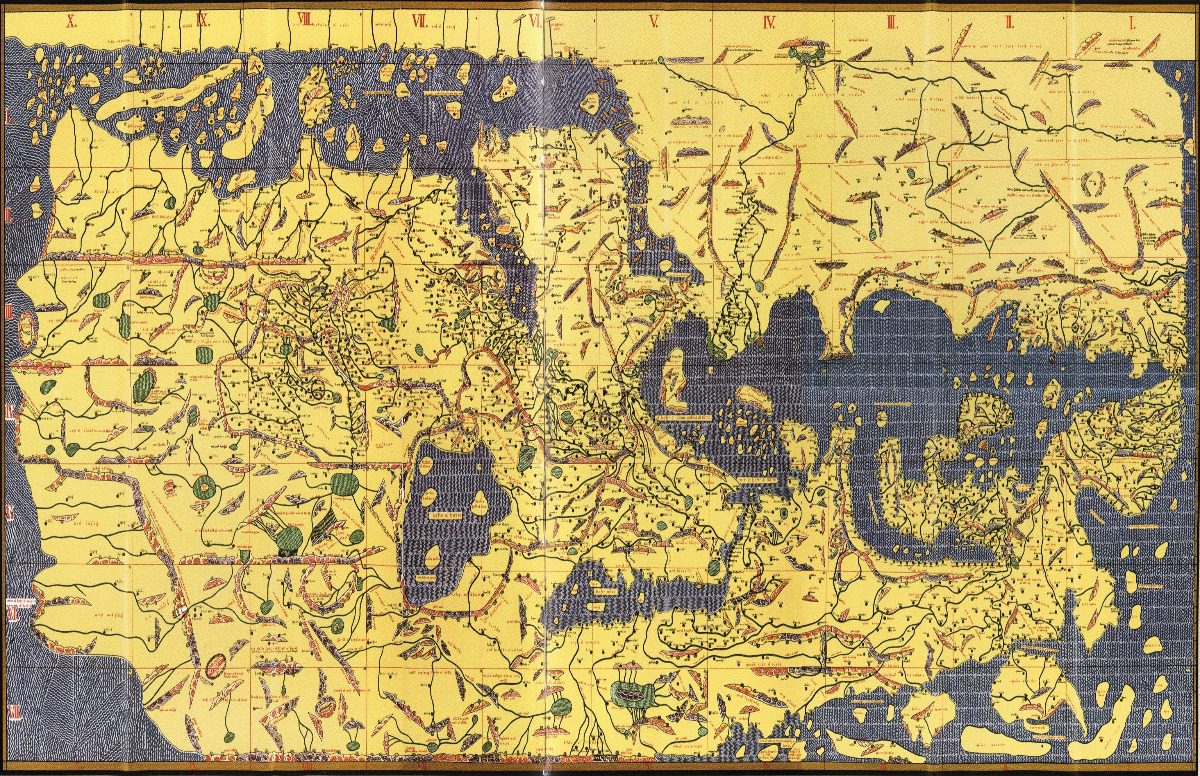

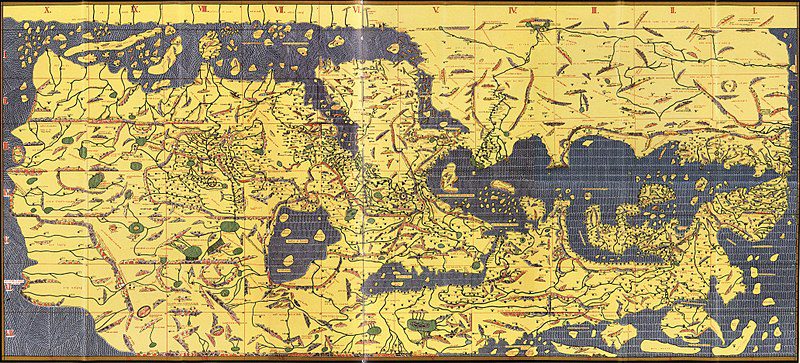

In 1154, Geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi produced the Tabula Rogeriana (The Recreation for Him Who Wishes to Travel Through the Countries), the most advanced map of the period. Not only did it depict areas with geographical accuracy, but it also included vast amounts of information about the areas mapped – including cultural and economic information and details about natural features. The map became the standard of cartography for several years and was used by travellers across the region.

In Europe, maps were largely made for educational purposes rather than navigation. Known as Mappae Mundi, medieval maps illustrated geographical concepts like direction, the locations of landmasses, and differences in climate. They were also used to tell stories about the world in religious studies, history, and mythology. The maps were often decorated with religious imagery and other drawings, focusing on aesthetic value and storytelling over realism.

Toward the end of the 15th century, increased interest in global exploration, trade, and the expansion of empires necessitated a return to mapmaking for navigational accuracy, spurring the greatest period of advancement in the history of cartography.

Early Modern Maps

During the ‘Age of Exploration’, Iberian travellers and cartographers explored new regions for the first time and gathered information on their journies. In the early 1500s, these expeditions, combined with mathematical principles revived from Ptolemy’s works, gave cartographers the knowledge they needed to produce nautical maps with greater accuracy. Spanish cartographer Juan de la Cosa travelled with Christopher Columbus and produced the first map depicting both North and South America (however, it only contained accurate depictions of the coastlines as inland travel was scarce).

By 1569, cartographer Gerardus Mercator used the global knowledge gained from the Age of Exploration to produce a map still used today – the Mercator Projection. A skilled mathematician, Mercator used cylindrical projection with straight, parallel lines of latitude and longitude to create his map of the world. By preserving shape but distorting size closer to the poles, the Mercator Projection greatly aided navigation – travellers could draw a straight line to any point on the map and use the direction to plan their journies accurately. Thanks to the projection, travel become simpler and navigators were able to map the interiors of continents, fostering a greater understanding of the world.

From The Industrial Revolution to Today

During the industrial revolution, the development of maps improved drastically. Mass printing encouraged cartographers to produce smaller maps for use by tourists, focusing on practical value over aesthetic or artistic value. Rapid advances in transportation and new knowledge about the world meant cartography was not a one-time pursuit – maps had to be constantly updated and adapted to be useful.

During the wars of the 20th century, maps became more important than ever in military strategy; so much so that Winston Churchill had a whole Map Room facility constantly in use by the Army, Navy, and Air Force during the Second World War. The Soviet Union’s chief cartographer in 1988 even admitted the government deliberately falsified maps in strategy during the Cold War, moving roads, rivers, and important landmarks.

In the late 20th century and now in the 21st century, satellites bring modern technology and cartography together. Computers, GIS (Geographic Information Systems) instruments, and the internet have introduced a new era of accuracy in cartography. More people interact with maps now than ever before, proving they are as essential and valuable now as they were in ancient history.

Read More: Mistaken Maps and the Myths They Perpetuated

Podcast Episodes about this topic

Articles you may also like

Why the Legions Beat the Phalanx

The societies of ancient Greece and Rome valued brawn as well as brains. Philosophers fulfilled military service and some of the most masterful speeches held in the senate or agora argued for war. However, it was the Romans that would end up dominating the Greeks, which was largely to do with the way they fought […]

The Battle of Kadesh and the World’s First Peace Treaty

For a shining example of ancient warfare and the cause of the world’s first recorded peace treaty, look no further than the Battle of Kadesh. By Madison Moulton. The characteristics of ancient warfare are often shrouded in mystery. There is evidence of the existence of early warfare, but intricate details of battle are scarce. However, […]