Mistaken Maps and the Myths They Perpetuated

Reading time: 8 minutes

Mapmakers in history occasionally got it wrong. Sometimes, very wrong.

By Madison Moulton

Maps are one of humanity’s greatest inventions. Early maps explain how humans understood the world around them, navigated, fostered trade, or conquered foreign lands.

They are also littered with mistakes and misrepresentations. Some of these mistakes were unintentional – the result of misinformation or inadequate mathematics – but many maps were purposefully altered in the pursuit of power, fame, or deception. While advances in technology have allowed us to identify some of these mistakes today, they often survived for centuries and greatly influenced the geographical perception of the world at the time.

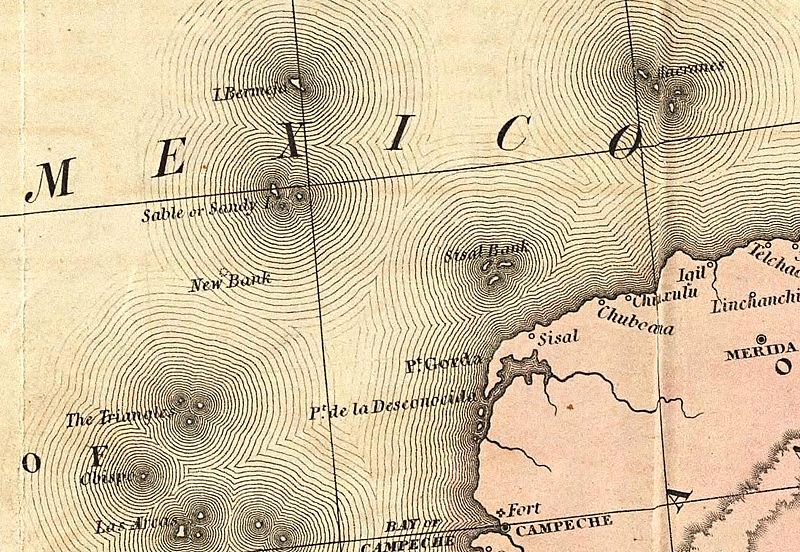

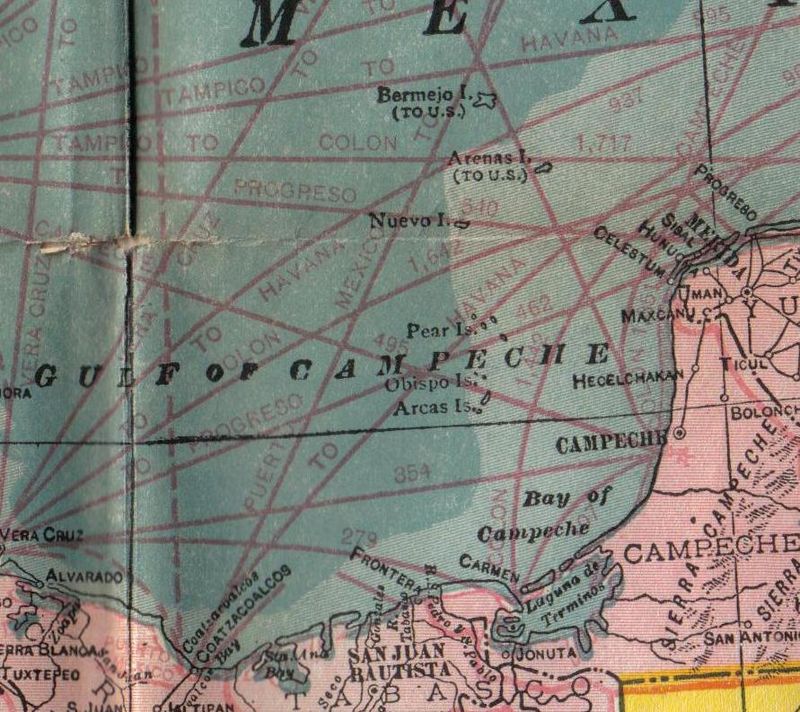

The Island of Bermeja

The mysterious Mexican island Bermeja first appeared on a 1539 map titled ‘El Yucatán e Islas Adyacentes’. First drawn by Alonso de Santa Cruz, it was named Bermeja “as it appears to be to such a colour”, referring to the Spanish word for red. A year later, the precise location of the island was described by Alonso de Chaves:

“Bermeja, an island in the Yucatan term, is at 23 degrees (north latitude). It is to the west quarter to the northwest of the Cape of San Anton, 14 leagues away. It is to the west-northwest of the Alacranes, 55 leagues away. It is to the northeastern quarter to the east of Villa Rica, 118 leagues away. This is a small island and looks red from a distance.”

Despite this incredibly detailed description from 1540, no evidence of the island has ever been found. Several expeditions to locate the island, including one by the Spanish army in 1775, failed and it was ultimately removed from world maps in the 20th century following doubts about its existence. The search for the island was revived in 1997 and again in 2009 by Mexican government officials and university researchers in the hope that it would extend the country’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) further into the Gulf of Mexico. However, the island remained a mystery.

Several theories have attempted to explain the island’s existence and subsequent disappearance – rising seas, shifts in the ocean floor, an inaccurate location, and even a conspiracy theory claiming the island was destroyed by the CIA.

However, most historians agree the most logical explanation is that the island never existed in the first place. It has been declared a phantom island, one of many examples of islands on early modern maps that were later found not to exist. Phantom islands were the result of misinformation, navigational errors, or intentional fabrication to identify map copycats. Bermeja, one 80 square-kilometre mistaken island, was replicated on maps for centuries and many people still hope for its discovery today.

The Magnetic North Pole – Rupes Nigra

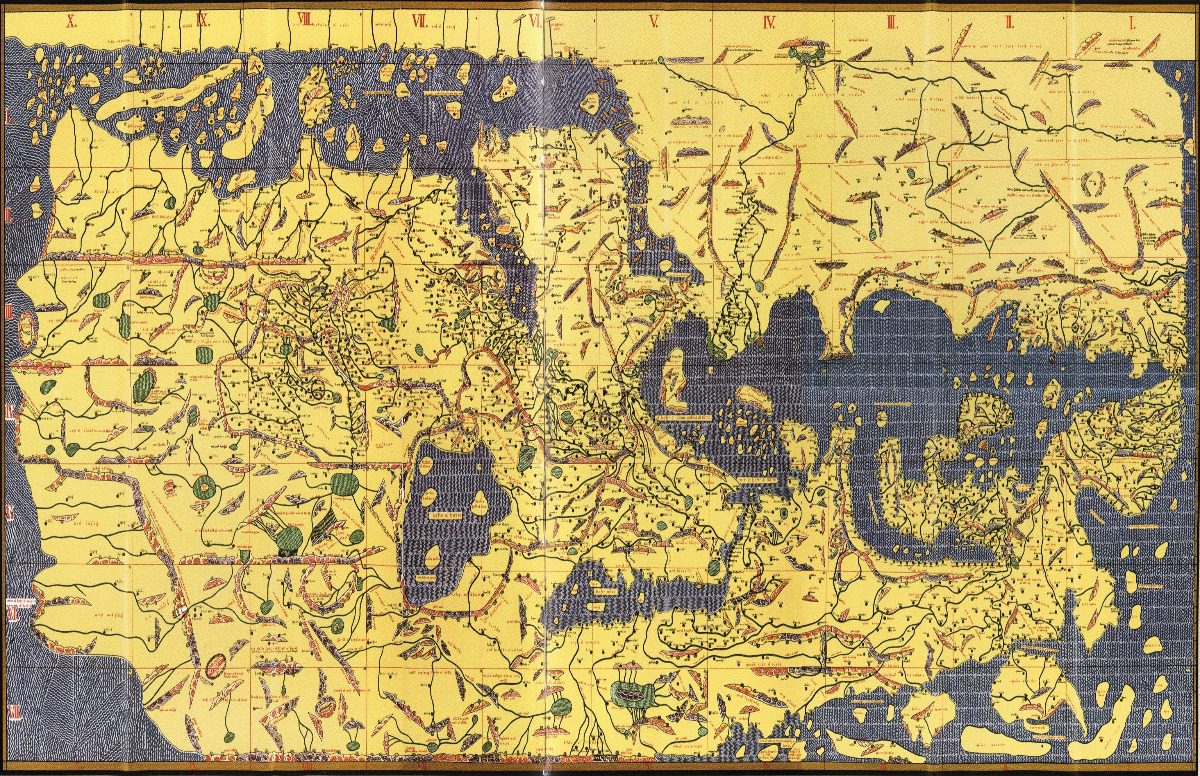

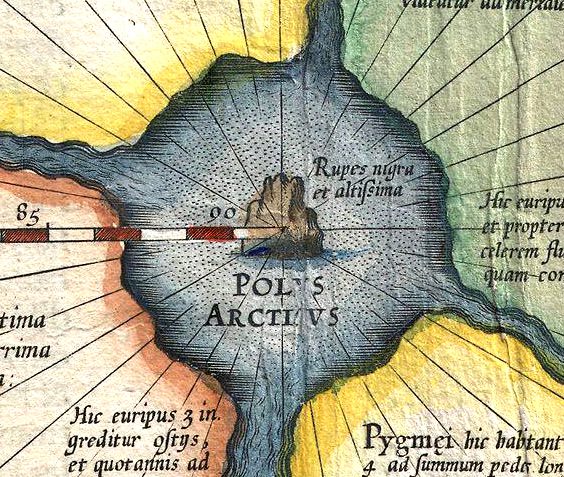

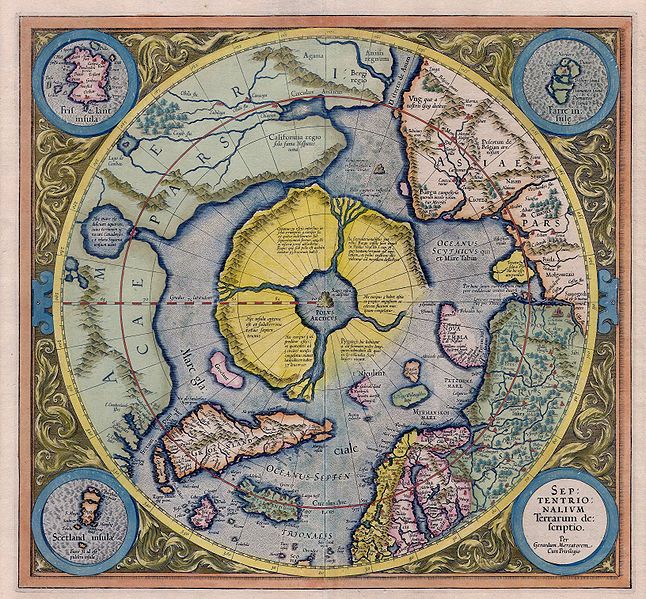

Another phantom island proven false far sooner than that of Bermeja was Rupes Nigra or “Black Rock”. This island first appeared on Gerardus Mercator’s 1569 map of the world (the famous Mercator Projection popular today) in his depiction of the Arctic and arguably the first detailed cartographical depiction of the Arctic in history.

As no explorers had traveled to the Arctic at the time, Mercator relied on a 14th-century account of the region in a book called ‘Inventio Fortunata‘. The book describes the centre of the North Pole as a magnetic island named Rupes Nigra (explaining why compasses always point north), surrounded by a whirlpool and four separate lands. Mercator describes the area in a 1577 letter:

“In the midst of the four countries is a Whirlpool into which there empty these four Indrawing Seas which divide the North. And the water rushes round and descends into the earth just as if one were pouring it through a filter funnel. It is 4 degrees wide on every side of the Pole, that is to say eight degrees altogether. Except that right under the Pole there lies a bare rock in the midst of the Sea. Its circumference is almost 33 French miles, and it is all of magnetic stone.”

With no other information to discredit the depiction, and the original ‘Inventio Fortunata‘ book lost forever, Mercator’s account of the Arctic survived into the 16th and 17th centuries. It continued to influence popular knowledge of the area until it was further explored, and Mercator’s depiction was proven false.

Frisland

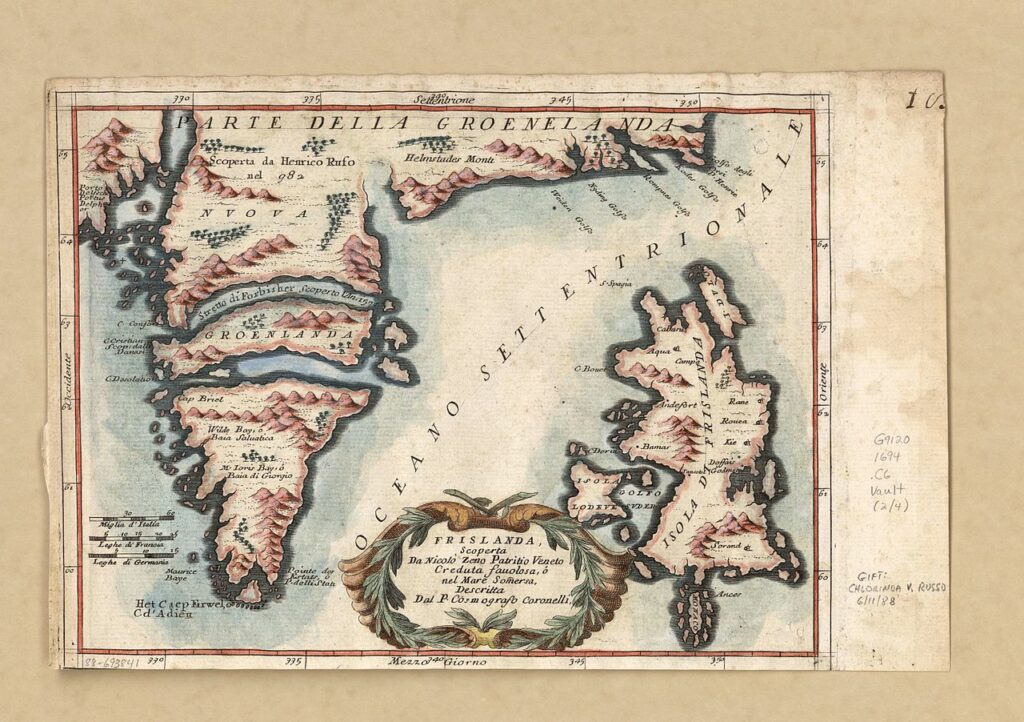

Frisland, also called Frischlant, Friesland, Frislanda, Frislandia, or Fixland, is a phantom island that appeared on virtually all of the maps of the North Atlantic from the 1560s through the 1660s, including those made by respected and influential cartographers like Ruscelli, Mercator, and Ortelius. This mythical island was purportedly discovered by the Zeno brothers in a 14th century voyage into the North Atlantic.

A landmass larger than Ireland, located south of Iceland, Frisland would have appeared to the viewer of the map to be a real place. They would have no reason to doubt it’s existence any more than they may would Greenland or Iceland. Its coastline was well-defined, with clusters of smaller islands surrounding it and a smattering of towns identified inland. English explorer Martin Frobisher even claimed to have landed there, proclaiming it ‘Anglia Occidentale’ in the name of Queen Elizabeth.

Frisland is by far the most detailed of the mythical islands. It is even more detailed than some of the actual islands depicted on contemporary maps. This increased it’s perceived legitimacy and lead to it being incorporated into maps by other cartographers.

The myth of Frisland was gradually dispensed with as many more explorers, chiefly from England and France, charted and mapped the waters of the North Atlantic.

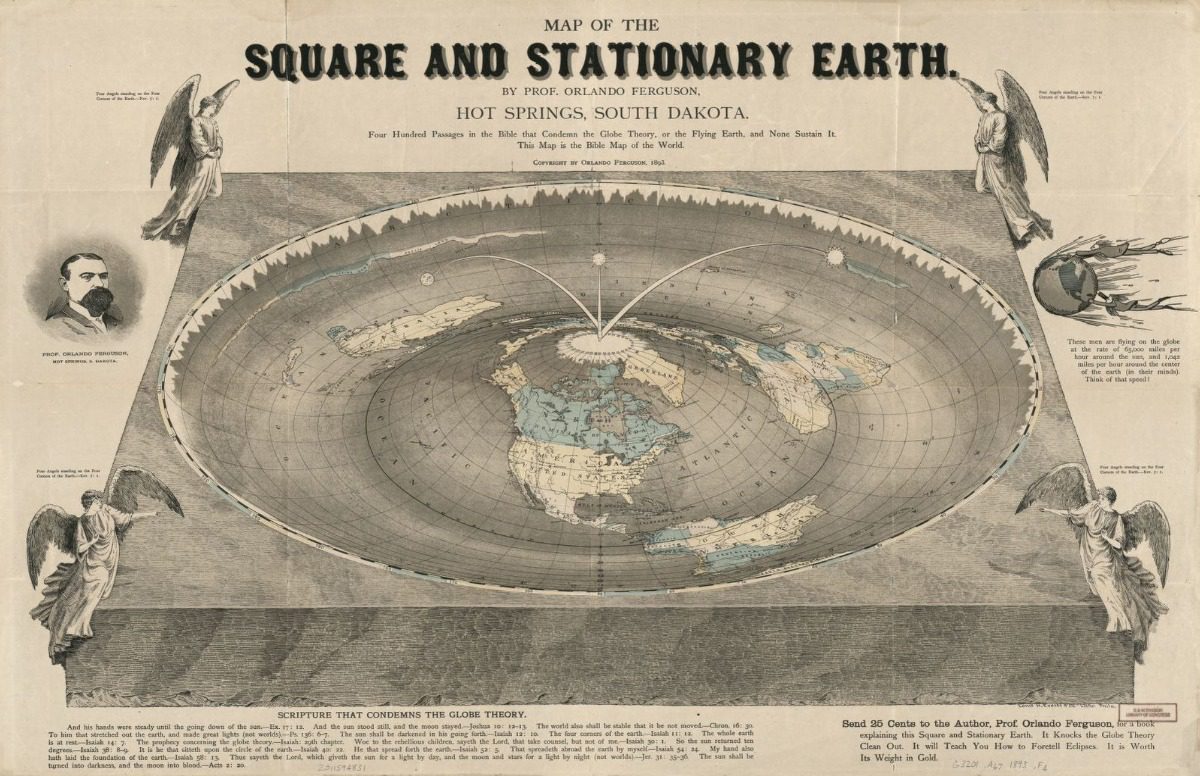

The Map of the Square and Stationary Earth

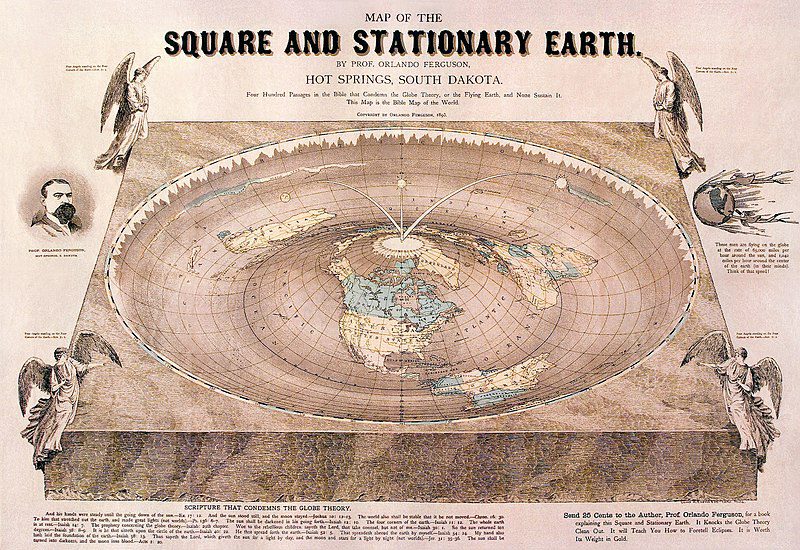

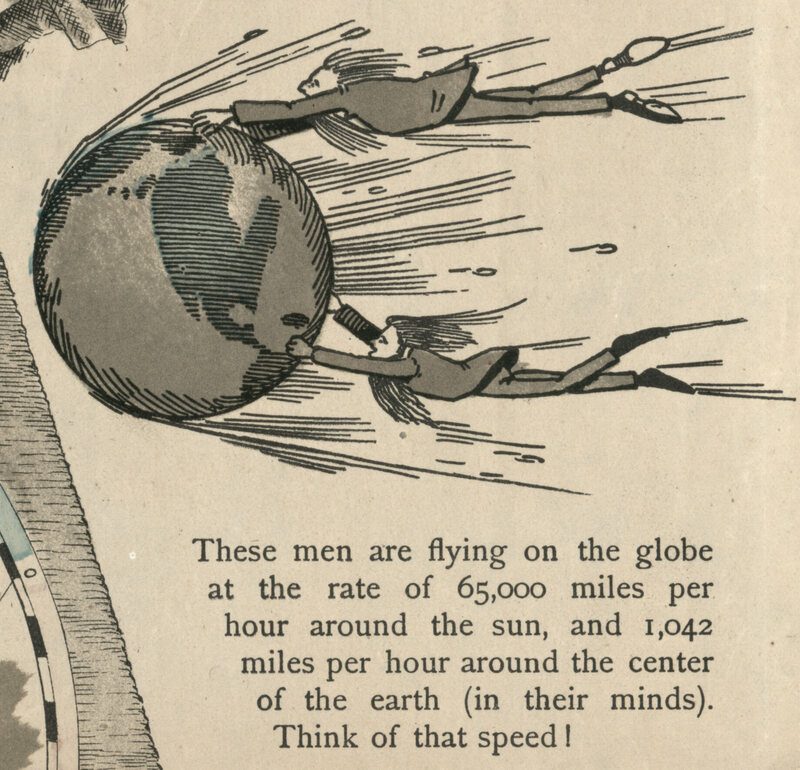

Other mistaken maps were not necessarily a result of misinformation, but rather a deliberate attempt to defend a certain narrative. For Orlando Ferguson in 1893, that narrative was that of a “Square and Stationary Earth”. Despite widespread acceptance that the earth is a sphere, Ferguson produced his own world map based on a literal interpretation of the bible. According to Ferguson, “Four Hundred Passages in the Bible that Condemn the Globe Theory, or the Flying Earth, and None Sustain It. This Map is the Bible Map of the World.”

The map depicts the earth as a bowl, with the sun and moon as satellite lamps rotating from the centre – the Arctic. The rim of the bowl is covered in jagged ice, Ferguson’s representation of Antarctica. Beyond the circular rim, the map extends to form a square with an angel at each corner, based on the opening sentence of Revelations 7 – “four angels standing at the four corners of the earth, holding back the four winds.”

Although his theory was not widely accepted at the time, or even widely known until the map was acquired by the US Library of Congress in 2011, Ferguson’s Map of the Square and Stationary Earth formed part of the resurging flat-earth movement of the late 1800s.

He joined the likes of Samuel Rowbotham, who wrote ‘Zetetic Astronomy and The inconsistency of Modern Astronomy and its Opposition to the Scripture‘ in 1849, and William Carpenter, who published ‘Theoretical Astronomy Examined and Exposed – Proving the Earth not a Globe’ in 1864. These ideas formed the foundations of the modern Flat Earth Society that still has a following today.

Whatever the cause of the mistaken map – incorrect navigation, lack of information, or intentional distortion – the ideas they produced were often perpetuated long after their initial construction.

Podcasts about this topic

Articles you may also like

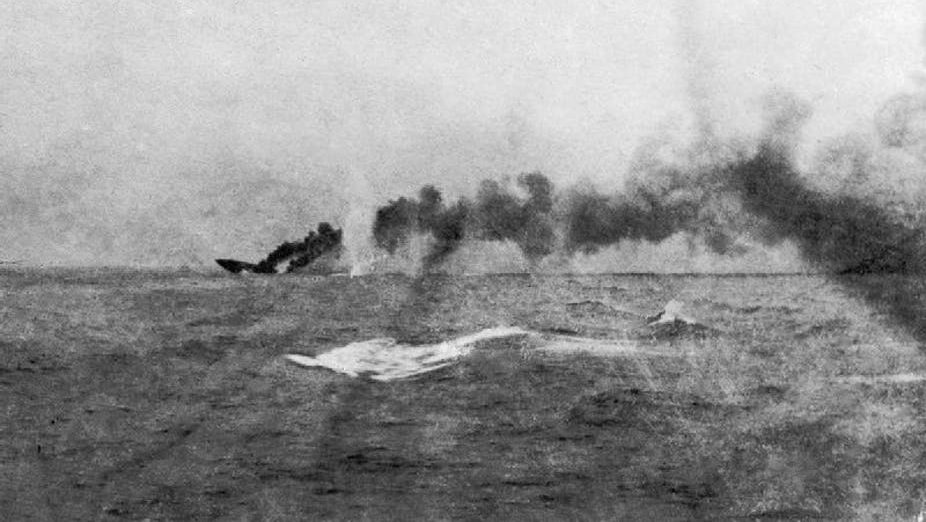

Jutland: Why World War I’s only sea battle was so crucial to Britain’s victory

By Andrew Lambert, King’s College London. Modern understanding of World War I is dominated by the immense human cost of the war on land with its trenches, artillery and machine guns – but the war was won by sea power. In August 1914 Britain, the greatest naval power of the age, controlled the oceans, cutting […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.