Reading time: 8 minutes

From Russian Constitutional Court chairman Valery Zorkin, to former Russian culture minister Vladimir Medinsky, to presidential adviser Yuri Kovlachuk, amateur history is everywhere in the Russian government today. This is not an accident but a deliberate way to build official state ideology in Russia. For instance, in a recent interview discussing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the deputy secretary of the Russian Security Council, Oleg Khramov, said that the West is trying “to stop the course of history” by “blinding” many Ukrainians to the historical truth of their shared civilizational identity with Russia.

By William Partlett, University of Melbourne

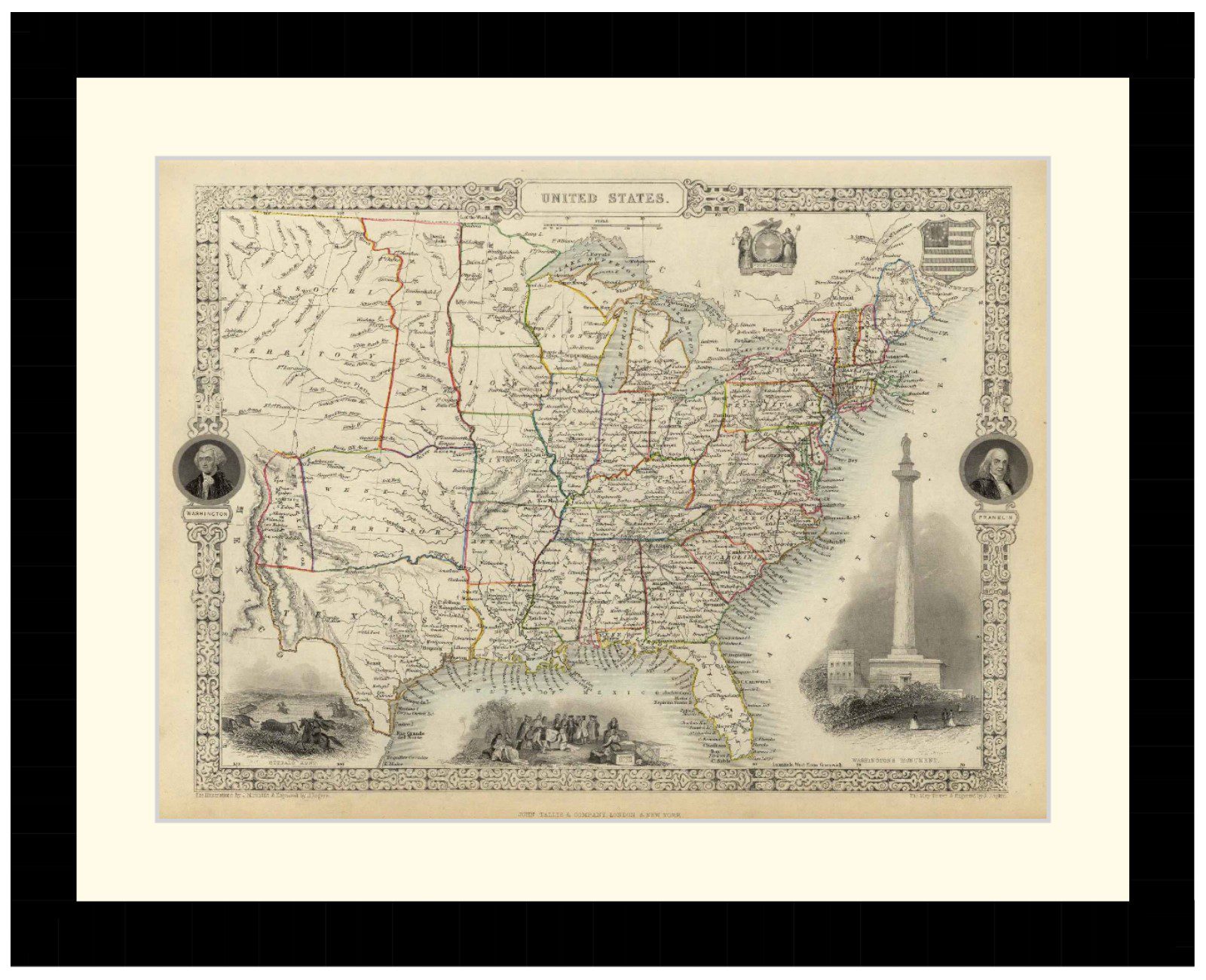

Vladimir Putin’s ideology has put new force into an old conflict between Enlightenment and Romantic notions of history. The Kremlin/CC BY 4.0.

Nowhere is this ideology more prominent than in the speeches of president Vladimir Putin. Russia’s amateur historian-in-chief frequently says that history was his favorite subject, and his spokesman has boasted that Putin possesses an “absolutely phenomenal knowledge of history.” Putin regularly describes the invasion of Ukraine as a technical decision required by history. In his telling, history proves that, from “time immemorial,” Russia and Ukraine were one. A separate Ukrainian identity from Russia, therefore, must be a project of external manipulation and an existential threat to Russia. The decision to invade, annex, and reeducate Ukrainians is not a political decision driven by contestable political values or beliefs. It is instead an objective decision that was unavoidable. To Putin, anyone opposing the invasion of Ukraine either does not understand this fundamental historical truth or is a traitor. History is now so important to official Russian discourse because Putin and many of his supporters genuinely believe that history provides objective, historical truths that govern the present. Their understanding of these historical truths, therefore, determines policy. This form of “ideological history” has become Russia’s official state ideology.

Ideological history has its own past, with roots in 19th-century German intellectuals. Reacting against an Enlightenment program that held that each generation should use reason to remake the world, these conservative thinkers argued that each generation must accept the world given to it. For instance, Friedrich Karl von Savigny, a leading Prussian historian, argued that the present naturally reflects the historically grounded and eternal Volksgeist (spirit of the people). This form of historical thinking developed into a critical reaction to revolutionary claims of a historical moment—often, the specific Enlightenment claims of the French Revolution. This approach was not without merit; history does indeed help us to understand why the revolutionary reconstruction of society can have unintended and deeply problematic consequences.

But in post–World War I Germany, this conservative understanding of history developed into something else: ideological history. Adolf Hitler—another strongman who declared history to be his favorite subject—placed it at the center of Nazi Germany’s ideological program. In particular, a central Nazi goal was the desire to “restore” a racially pure German nation to its rightful place in the world. This historical mission was then used to justify Germany’s territorial expansionism and genocide.

Putin and many of his supporters genuinely believe that history provides objective, historical truths that govern the present.

As an approach to the past, this kind of ideological history has two key problems. First, its adherents do not seek to understand history by critically engaging with the existing source material. Instead, they create a selective historical narrative that fits a preexisting political ideology. For the Nazis, their political commitments helped to generate an invented narrative about the racial purity of the German people in the past and its “pollution” in recent centuries. This ideological use of history therefore cloaks a political agenda in the language of history.

Second, adherents of ideological history view history as a repository of immutable truths that must be preserved or restored today. History is therefore something that determines the present and requires certain types of action today. A critical approach to history, of course, shows that opposite: even if we adhere as closely as possible to the source material, the questions we ask of history invariably change over time. As E. H. Carr wrote, history is “a continuous process of interaction between the historian and his facts, an unending dialogue between the present and the past.” Historians must seek to critically understand how the present drives our historical understanding and how that history shapes our actions today. Denying this critical process risks creating an authoritarian ideology cloaked in the language and narratives of history.

Both of these criticisms can be leveled against Putin’s historical narrative about the invasion of Ukraine. First, his account of the historical unity of Russia and Ukraine selectively draws on historical facts to construct the story of an immutable, Russian civilization that naturally includes Ukraine. This story of unity is not new: it was developed by Russian officials and intelligentsia in the imperial era to justify Russian power over its lands. The second criticism, however, is equally important. Even if we accept Putin’s historical narrative of civilizational unity, why must this unity continue into the present? Why deny the Ukrainian people today the ability to build an independent identity that breaks with a form of historical unity that itself stems from Russian imperialism?

These critiques not only show why the invasion of Ukraine was not required by history. They also uncover the fundamental tenets of Russia’s post-Soviet form of ideological history. This ideology is about defending a historical story about Russia’s natural civilizational and imperial identity and position in the world. In contrast with the Soviet period, today’s ideology does not make universal claims about remaking the world; it instead makes identity claims about Russia’s natural and eternal place within it. Further, unlike in the Soviet era, this new ideology does not rely on conceptual categories such as the superstructure or class but instead reflects an emotional fantasy of restoring an imperial past in which the Russian world and its unique civilization (including Ukraine) balance against a decaying West. Russia’s new state ideology is not a forward-looking commitment to a coming communist society but a backward-looking one to defend an imperial version of Russian civilizational identity found in history.

Putin is not alone in developing this kind of ideological history. Similar forms of history are being developed in Xi Jinping’s China and Narendra Modi’s India. For instance, Xi recently told US president Joe Biden that both countries should use history as a “mirror” and let it guide the future. This broad use makes it tempting to see this return of ideological history as simply self-interested justifications of personal power. But these arguments reflect more than that. They draw force from a legitimate critique of the post–Cold War order and its own claims about the “end of history.” Led by the United States, post–Cold War triumphalism includes a confidence that certain best practices—often derived from the United States—should be transferred universally around the world. For instance, the Washington Consensus of the 1990s advocated a standardized set of rapid, free market reforms for the entire former communist world.

In many places—most notably, Russia—the implementation of these best practices had unintended consequences, including the creation of vast economic inequality. A historical critique is an important response, holding that national history and context should have been taken into account in shaping these reforms. Such a critique therefore echoes the 19th-century German criticism of the Enlightenment-era claims of the French Revolution. Taken critically, historical ideology is an important corrective to an idea that history no longer matters in the face of rational, universal best practices.

But, as in 1930s Germany, history in the minds of strongmen in Russia, India, and China today is not used critically. The return of ideological history threatens to rob new generations of their agency. And authoritarian governments enforce this view of history through law, including it in government-mandated history curricula. In Russia, this official history is also officially enforced by laws forbidding the “falsification” of history, what has been called “rehabilitating Nazism.” In part, these laws criminalize any challenge to the historical myth that Ukrainian independence from Russia is purely the cynical creation of Nazi Germany during World War II. Since 2014, dozens of professional Russian historians have been imprisoned or fined under these laws.

This failure to perceive the deep roots of Ukraine’s independent identity led to the Russian fantasy of a three-day march to Kiev.

This ideological history is not only authoritarian. It can detach its adherents from reality. Once they find their truths in history, strongmen will then filter the outside world through these perceived truths. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was exactly that: a response to the perception that an increasingly independent Ukrainian identity must be the result of external manipulation. This failure to perceive the deep roots of Ukraine’s independent identity led to the Russian fantasy of a three-day march to Kiev with Ukrainians greeting Russian tanks with flowers. More broadly, it leaves one worrying about the policy consequences of China’s historical claims to Taiwan or Modi’s restoration of India as a Hindu state.

The historical critique of post–Cold War universalism, though necessary, need not lead to a return of ideological history. Critical history can inform intelligent present-day policymaking without becoming a backward-looking discourse of historical nostalgia. In this understanding, history can be a place of critical departure and change. Constructive engagement with history can be a powerful way of reforming in a way that respects important traditions within a particular country. Although this kind of critical history is currently illegal in Russia, nongovernmental historical organizations like Memorial and a generation of professional historians (some of whom are in jail) await a new Russia where they can restart their projects. In this work, Russian history is not a place of nostalgic return but an important resource for change.

This article was originally published in The Perspectives on History.

Podcasts about Putin’s education and upbringing

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 81

History Guild General History Quiz 81See how your history knowledge stacks up! Want to know more about any of the questions? Once you’ve finished the quiz click here to learn more. Have an idea for a question? Suggest it here and we’ll include it in a future quiz! The stories behind the questions 1. Which […]

The wild decade: how the 1990s laid the foundations for Vladimir Putin’s Russia

Reading time: 6 minutes

By securing victory in a national vote on constitutional changes, Vladimir Putin could now remain president of Russia until 2036 if he chooses to stand again. After 20 years in power, the narrative of Russia’s chaotic 1990s remains core to Putin’s legitimacy as the leader who restored stability.

The text of this article is republished from Perspectives on History and is is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.