Estimated reading time: 8 minutes

The societies of ancient Greece and Rome valued brawn as well as brains. Philosophers fulfilled military service and some of the most masterful speeches held in the senate or agora argued for war. However, it was the Romans that would end up dominating the Greeks, which was largely to do with the way they fought in battle. In this article, we’re going to explain why Rome won by comparing its legions to the phalanx.

By Fergus O’Sullivan

To do so, we’ll be using screenshots from the game Total War: Rome 2. It’s one of the most historically accurate video games out there, and will do a better job than we can: our artistic skills are limited, at best. It also gives us an excuse to play a video game and call it work, which is always good.

We’ve used Rome 2 to simulate history before, when we reenacted the Punic Wars between the republic and Carthage. For that article, we used Mike Duncan’s excellent podcast The History of Rome as the red thread, and we’ll use his insights for this piece, too. Mainly the two episodes named A Phalanx with Joints, though a few others as well; we’ve linked the playlist at the end of this piece.

A Hedge of Spears

To kick off our comparison, we’ll start where it all began: Greece. Though there is evidence of the Sumerians fighting in phalanx-like formations — and maybe even by the Egyptians and the Hittites at the battle of Kadesh in 1274 BCE — it was the Greeks that perfected this method of warfare.

There is some dispute on whether it originated in Sparta or Argos and in which century exactly, but generally we can assume that around 600 BCE or so most Greeks fought in this manner, which involved forming a mass of men that presented a wall of shields and spears toward the enemy.

This alone wasn’t all that revolutionary: generally speaking it’s a good idea to point your weapon at whatever it is that you’re trying to kill. However, the Greeks did things a little differently and made their version of the phalanx particularly deadly.

For one, they packed men in tight, leaving as little room as possible between soldiers — known as hoplites for their massive shields, or hoplon — on each side. Each man’s shield covered the man to his left, meaning you were covered by the man on your right. This made for strong unit bonding, as your life very much depended on the guy next to you.

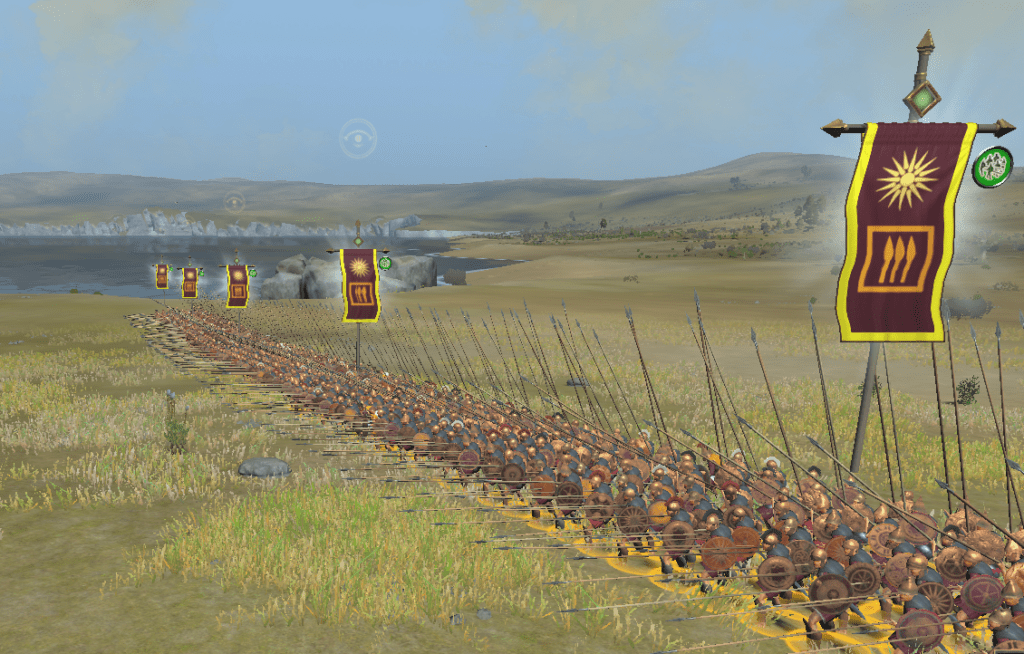

On top of that, the Greeks packed men in tight behind the front line, too, generally as deep as eight men, though lines regularly could have 16 men behind them. The end result looked a little like this.

As you can see, it was only the first four or so lines that had spears stick out past the shields, giving the appearance that those guys at the back didn’t contribute much. When factoring only the stabby part of the whole procedure, you’d be right, but their real job wasn’t to kill the enemy, it was to apply pressure on their comrades.

In a battle between a phalanx and a charging mob, which was the other common tactic of the day, the phalanx won each time, without breaking a sweat. The warriors of the other side would simply be skewered as they ran toward the phalanx. However, in a phalanx vs phalanx battle, it was all about pressure. The harder you could push your guys into the other guys, the bigger the chance you’d win. As added benefit, exerting pressure from the rear meant the guys at the front couldn’t run away, guaranteeing the cohesion of the formation.

Phalanx Weaknesses

The key of a phalanx’s success was unity, it needed to stick together to work. Any hole could be exploited, and if a phalanx got cracked it was game over. Another problem was that, while it was unassailable from the front, it was ridiculously weak from the sides and back. The tightly backed formation could not wheel about and meet a threat easily. Thus, a phalanx was great in Greece, where narrow mountain passes, like at Thermopylae, were the norm: the enemy had no choice but to go into the teeth of your spears.

However, on open ground a phalanx was toast, and also on an uneven battlefield: if just one man would trip up on a loose rock or a molehill, he could potentially take a whole chunk of the phalanx with him.

The Phalanx and Roman Ingenuity

During the first few years of Rome’s existence, the Roman army fought in the pell-mell style of most disorganized tribes: just charge the enemy and hope for the best. Relatively early on the republic adopted the phalanx and many of its first victories were won with spears outstretched. However, during Rome’s war with the Samnites, a hill tribe that used the rocky, sloping terrain of their homeland to the fullest, the Roman army quickly ran into the limitations of the phalanx.

After several devastating losses to the Samnites, the Romans went soul searching and realized the phalanx was the cause of their problems. The inflexibility of the formation was destroying them and costing the lives of thousands of brave soldiers. Not ones to sit around, an alternative was quickly devised in the form of the maniple system in around 315 BCE.

This new system was based around a unit of 120 or so men, called a maniple, a term which was derived from the word for “handful” (manipulus in Latin). Each maniple was made up of two centuries (despite the name, a century didn’t have a hundred men, usually more like 60 to 80).

Unlike the phalanx, which was just one long unbroken line of men, each maniple would be ordered about independently. If a new threat popped up on the flanks during battle, for example, a general could peel off one or two maniples and send them to reinforce the sides, or even make an about face and meet an enemy coming from the rear.

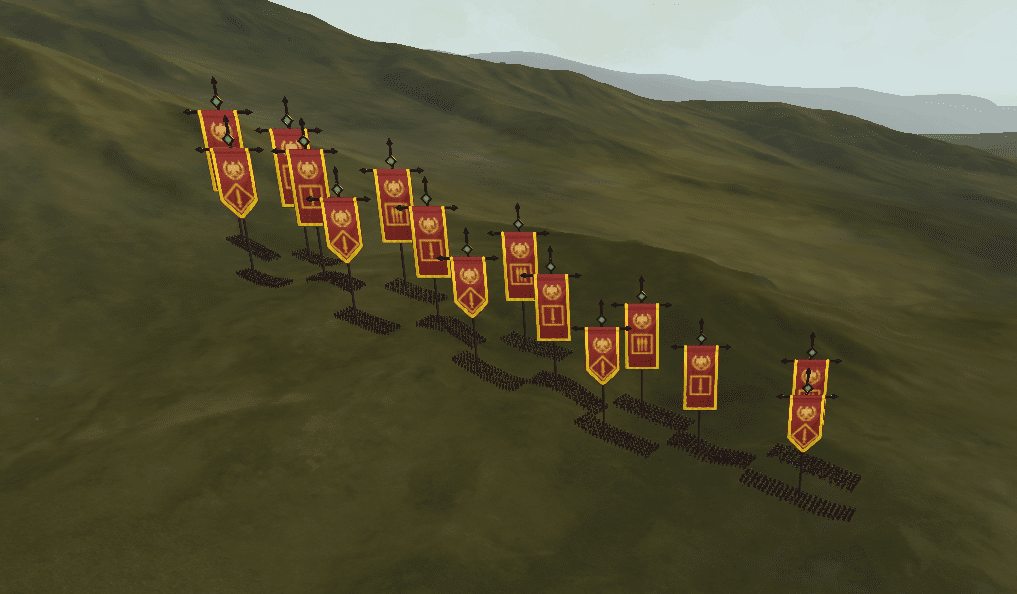

This was in itself a smart innovation, but the Romans didn’t just change their unit structure, they also adapted the way a whole legion fought. Instead of the single line of the Greeks, maniples would assemble in a checkerboard pattern, three maniples deep and as much as 15 maniples long, though more often around 10. The third line would usually be at half strength, as there weren’t that many old men to go around in ancient times.

The front line was made up of the youngest, most energetic soldiers, the second line was made up of older men (between 20 and 40) and the third, rear, line was made up of the oldest, toughest veterans Rome could muster. The logic was that the first line would engage, then, once their youthful vigor ran out, the second line would fill up the gaps and if that was somehow not enough to stem the tide, the last line would come in and show the young’uns how things were done.

Even if this age-based system — which interestingly reflects the way the Romans venerated old age — wasn’t always strictly adhered to, the idea behind the three ranks made a lot of sense and added flexibility to an entire army the way the maniples added it to units. The flanks were still vulnerable, but the Romans would usually have allied cavalry and light infantry there to protect the Roman heavy infantry, and a commander could always order a few individual maniples to help them out if things got too hot on the flanks.

Also, during the first few decades the maniple system was in use, the main force would be screened by skirmishers at the start of the battle. They would harass the enemy a bit, before melting away between the maniples’ gaps when the battle started properly.

Roman Results

The effectiveness of the maniple system wasn’t just on paper. Though it took the Romans decades to finally subdue the Samnites, they never suffered another defeat after changing over to maniples. The biggest test, however, was in the Macedonian wars, when Rome went over to Greece to impose its kind of order.

In a head-to-head battle with Macedon, with their armies that Alexander the Great marched all the way to India, the Romans trounced them in the battles of Cynoscephalae and of Pudna. Though the maniple system would eventually be updated by Marius in 107 BCE, it stood the Romans in good stead for 250 years, more than proving its worth.

Articles you may also like

The Battle of Kadesh and the World’s First Peace Treaty

For a shining example of ancient warfare and the cause of the world’s first recorded peace treaty, look no further than the Battle of Kadesh. By Madison Moulton. The characteristics of ancient warfare are often shrouded in mystery. There is evidence of the existence of early warfare, but intricate details of battle are scarce. However, […]

The History of Games: Rome 2

By Fergus O’Sullivan. Here at the History Guild we like video games, especially ones with a historical setting. Of course, plenty of games marketed as historically accurate aren’t, especially to history enthusiasts. In this series, we’ll be taking a look at some of the bigger games around and seeing if they’re really as true to […]