HOW A CYPRUS MUSEUM USES TECH TO MAKE THE PAST COME ALIVE

What do you do when a building important to your city’s history is inaccessible? When you can see it, but simply cannot get anywhere near it? This is the question facing the Ledra Palace Hotel in Nicosia, the capital of Cyprus and one of the last few divided cities in the world. One group of researchers seems to have found a solution, using cutting edge tech.

By Fergus O’Sullivan

Up until the Turkish invasion in 1974, the Ledra Palace Hotel served as a social hub for the elite of Nicosia. It hosted countless receptions, gatherings and other events for the many communities present on the island: Greek Cypriots, Turkish Cypriots, Armenians and British, they all used to mingle underneath the chandelier in the main ballroom. It also hosted scores of foreign dignitaries and their entourages.

A fascinating location to be sure, but if you try to visit it now, you’ll run into barbed wire. When the ceasefire was declared between the invading Turkish army and the Republic of Cyprus, the Ledra Palace found itself firmly in the UN buffer zone meant to keep the peace between the two sides.

The closest you can come to the hotel now is as you pass by it when traveling between the checkpoints, one on either side, that divide the island. There’s no time to take a tour, either: the area is used as a British army barracks and there’s a firm “no dawdling” policy.

Ledra Palace: Dancing on the Line

Cut off from the world, the story of the Ledra Palace could be written off as just another lost piece of history like so many others. However, a team of researchers from the CYENS Centre of Excellence and the Leventis Municipal Museum of Nicosia have put together an exhibition that has brought the hotel back to life in its former glory. Instead of bricks and mortar, though, they’re using bits and bytes.

Named Ledra Palace: Dancing on the Line, the exhibit has done away with the serried ranks of glass cases you might expect. Instead, it uses its allocated space on the top floor of the museum to place a wide selection of technological gadgets, ranging from a very large screen, to an interactive table and virtual-reality headsets.

Each of these installations has as its goal to tell a story, either that of an object associated with the hotel, or that of a person who worked or lived there. The resulting narrative isn’t just about the Ledra Palace, either, but also offers a glimpse of a Cyprus where its two largest communities lived together in relative harmony.

The need for this is quite simple: according to Antigone Heraclidou, one of the three curators of the exhibition, “modern Cyprus history is not a vital part of history class in schools.” As such, a narrative has developed on either side of the line that portrays the other as the enemy and has pretty much wiped out any memory of an undivided Cyprus.

We talk about this in detail in our article on how Cyprus was divided.

As Dr. Heraclidou ruefully admits, no one exhibition will remedy decades of ethnic tension and venomous propaganda, but she, the research team as well as CYENS technical arm, headed by Kleanthis Neokleous, have made a solid effort.

The Exhibition

Not the simplest of tasks, but the team behind the exhibition came up with some amazing installations. The biggest one, which serves as the eyecatcher, is a large wall divided into ten screens, each of which features one person explaining the effect the Ledra Palace has had on their life.

These range from a British soldier who used the hotel as his HQ while patrolling the buffer zone, to a Cypriot national guardsman who was part of the battle surrounding the hotel in 1974. Also featured are the wife of the man who managed it, as well as her daughter, who is now one of the people in charge of the project.

The story is told organically, with one interviewee telling one part of their story, then another taking on that thread before passing the torch to another. Though all eight interviews were conducted separately, whomever did the editing of these videos did a stellar job. It really brings home the importance a building can have to a community and sets the right mood for visitors.

Dr Heraclidou, though, has one regret when it comes to the videos: there are no Turkish Cypriots being interviewed. Apparently there was one veteran of the fighting in ‘74 who initially was interested in being part of the project, but the team wasn’t able to make it to his side of the zone thanks to the pandemic lockdown. Eventually, the man changed his mind, leaving visitors without a Turkish Cypriot voice on the wall.

Immersive Technology

However, as impressive as the wall is, it’s the other installations that make the exhibit truly immersive. First is an interactive book which tells the story of recent Cypriot history through images and video, though there’s some text when necessary to explain complicated parts.

The team chose to go with an actual book here, even made of paper, and then project the content from above. It’s a pretty nifty way of doing this, and gives visitors a great understanding of the history.

Going light on text was a conscious choice by the team: the aim of the exhibit is to be non-authoritative, to let visitors make up their own mind about Cypriot history. Overexplaining images would run contrary to that. Instead, the pictures of Turkish and Greek Cypriots enjoying events together tell their own story, of a much more inclusive society.

The book takes a novel approach to an old concept, but the next installation takes it even a step further. Where most museums would have you simply walk past a glass case containing objects, this exhibit lets you interact with them directly, or at least with replicas.

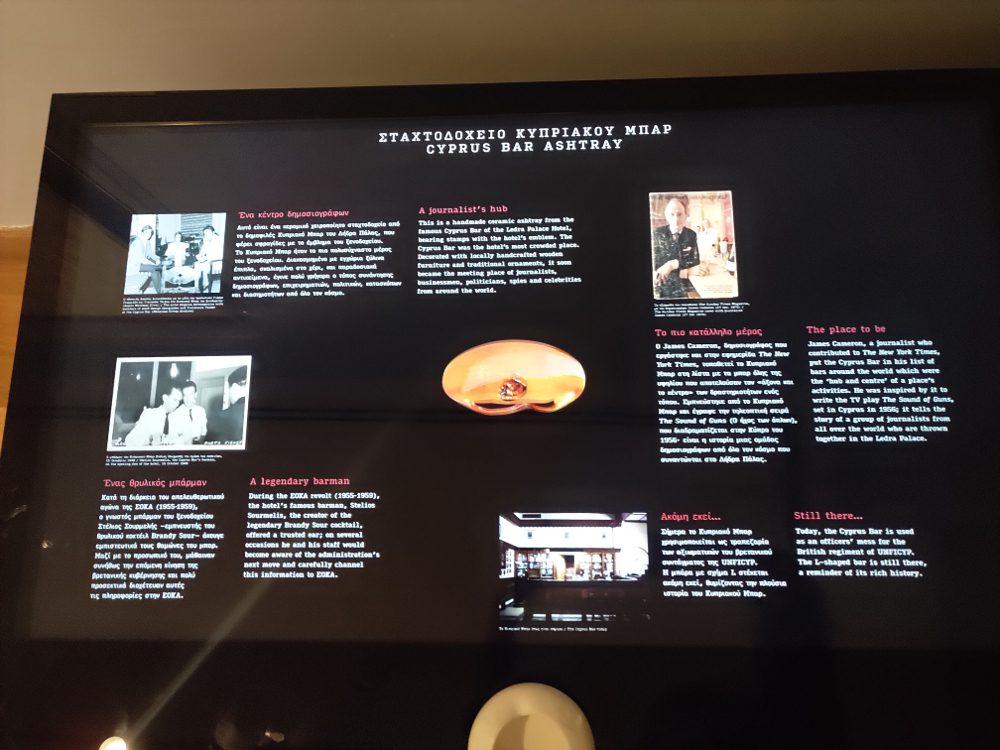

While the exhibit does have a conventional display of objects retrieved from the Ledra Palace — though less than you think as the hotel was heavily looted during and after the invasion — the team has picked five objects that tell a deeper story. These include the key to room 105 of the hotel, an ashtray and a book.

Each of these five objects has a 3D-printed replica placed nearby on an interactive table, which visitors can pick up and then place on the table to get the full story behind it. The key, for example, explains that almost no other keys were found, while the ashtray talks a little about the bar of the hotel and the people that worked there.

Though it may seem like it’s not a big step up from just placing an object in a case with a card explaining it beside it, having a tactile interaction with a historical object — even a plastic version of it — creates a bond of sorts, as silly as that seems. When you later see the object in a case, you remember it better, and you want to know more about it. It’s a very interesting experience.

Virtual Realities

All these installations lead to the exhibit’s main event, a virtual reality experience of the hotel in its heyday. The team chose a seminal event in the history of the hotel, namely the last reception held by the last British governor, the day before handing over independence to the Cypriot people.

Dr. Neokleous explains that the reconstruction was made using pictures gathered from several sources, as well as using details gleaned from interviews with people who were there. This information, as well as some educated guesswork, led to a pretty impressive experience which makes you feel, in some small way, like you were present at the dinner.

Funnily enough, though, according to Dr, Neokleous, when the interviewees experienced the VR simulation, they all praised the level of detail, including the colour of the drapes. However, when the colour was adjusted a little and then shown to the same people again, they praised it again. Memory is a tricky thing. Still, though, the VR experience feels close enough to real life.

That said, it does require some suspension of disbelief. The biggest flaw is probably that the people present at the dinner — or other people, excluding yourself — seem a bit like cardboard cutouts.

Dr. Neokleous explains this is for two reasons: the first is historical, despite some deep digging, the only person whose location at the dinner they’re completely sure of is Cypriot President Archbishop Makarios, and that’s really only because of his massive hat, called a “kalimavkion,” without which he seemingly never left the house.

Where anybody else is seated is pretty much guesswork, though. The other issue is technical, to make the simulation run smoothly, the guests couldn’t be fully rendered. It seems to have been a wise choice: there’s no stutter or any other tell-tale signs of performance issues so common in VR.

Where Past and Present Meet

The last section of the exhibit is a virtual tour of the Ledra Palace as it stood in 2019; thankfully access was granted before the pandemic hit. After seeing pictures and videos and reconstructions of the hotel at its zenith, it’s odd to see what it looks like now. Gone are the throngs of people and the elegant furniture, replaced by much more utilitarian tables and chairs and announcement boards for the soldiers using it as a mess.

Still, though, you catch some interesting glimpses of the past. The ballroom, which you just saw from the point of view of a diner, is still the same shape and form, even if the chandelier is missing. It’s a testament to the technical team’s work that you recognize it so readily. Being shown around the halls of the Ledra Palace in this way almost makes you nostalgic, despite never having set foot there.

Past Is Prologue

In a way, that’s the proof of the efficacy of the team’s mission. According to Dr. Heraclidou, they have had to replace the guestbook shortly before my visit due to it being so full of positive feedback. Younger visitors seem to enjoy the technology for the sake of it, and then learn something about the past of their island. Older people seem more apprehensive at first, but then embrace it as a way to see the world again as they remember it.

The universal reaction, though, seems to be surprise: many visitors, regardless of their identity, simply did not know that Greek and Turkish Cypriots lived a life together, and even had a place like the Ledra Palace for mixed events. Hopefully that message is one that carries forward into the future.

Right now, that future looks a little uncertain for Dancing on the Line. The exhibition closed on the 31st of October 2021, though the team behind it is now looking at ways to make it a fully virtual experience that can be used to educate people about a more inclusive Cyprus wherever and whenever they may be.

Articles you may also like

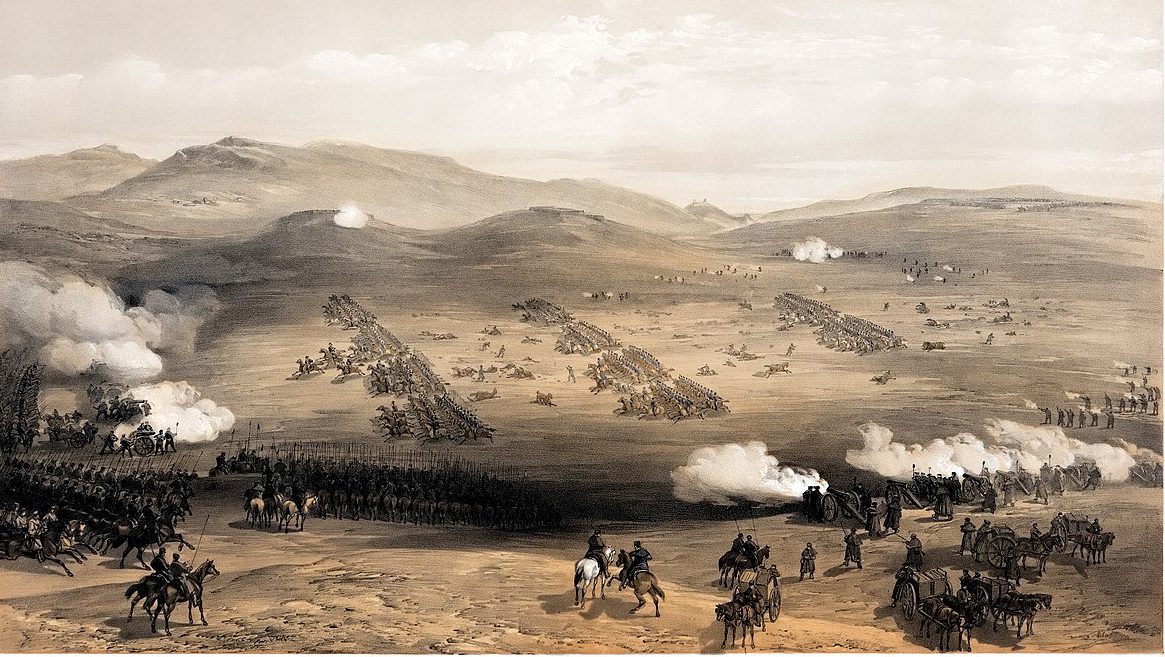

Could the Charge of the Light Brigade have worked?

COULD THE CHARGE OF THE LIGHT BRIGADE HAVE WORKED? Middle East tensions. Russian soldiers in Crimea. Western nations’ warships in the Black Sea. Those descriptions sound like Russia’s 2014 takeover of Crimea. But they also applied 150 years earlier during The Crimean War between Russia and a British-French-Turkish alliance. That war is largely forgotten now, apart […]

The other assassination of November 1963

Reading time: 5 minutes

On the night of 1 November 1963, President Ngo Dinh Diem of the Republic of Vietnam (commonly known as South Vietnam), and his brother and chief political adviser, Ngo Dinh Nhu, were assassinated during a coup executed by a military junta, acting with the knowledge and support of the United States.

History’s Greatest Nicknames

Reading time: 7 minutes

A browse through any military history book will no doubt bring up titles of famous officers, often bearing unusual, surprising, or sometimes downright hilarious nicknames. In many cases, it’s clear where the sobriquet originated, while other examples hold a less-obvious significance.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.