Reading time: 1 minute

Generally speaking, making an archive accessible to the public isn’t something covered by the national news. However, in the Netherlands a massive public debate was sparked when an archive with the files of over 400.000 people suspected of collaboration with the Germans during World War 2 was to be opened up.

By Fergus O’Sullivan

To understand the uproar, it’s important to understand the difficult relationship between the Netherlands and its wartime history. Though through its long history it had been no stranger to invasion (or invading other countries to patch together its colonial empire), it had thought itself safe from European war ever since successfully staying neutral during the First World War.

The Netherlands during the war

When the German war machine thundered over the border in May 1940, this illusion was shattered. Though at first the occupation wasn’t too bad, as Aryan Brudervolk the Dutch were spared the horrors countries like Poland and Ukraine lived through, the loss of freedom and the mass deportation of Dutch Jews made clear the eastern neighbour hadn’t come for the good of the Dutch people.

Or, at least, not for all Dutch people. A pretty unpleasant fact of the occupation was that many Dutch people gleefully joined the Dutch national socialist party (NSB, or Nationaal Socialistische Beweging, founded in 1931 on the German example) and collaborated with the occupier. Exact numbers aren’t clear. It is known to be at least 30.000 members, but it was likely a lot more — but the Germans found that many tasks of running the country were handled by locals that shared their ideology. Even more telling are the 25,000 volunteers that joined the Waffen SS to fight on the Eastern Front, the highest number of volunteers of any occupied country.

Another sad statistic is that likely as much as 90 percent of the Jewish population was murdered during the five years of the occupation. Only Germany itself lost more, and it would have been impossible without the cooperation of the Dutch authorities and NSB members.

Dealing with the past

After liberation, the Dutch post-war government was presented with a massive heap of issues, not the least of which was how to deal with the many collaborators. To deal with this, tribunals were set up under a system called “special legal proceedings” (bijzondere rechtspleging), a term that by design covered all manner of sins.

While these proceedings generally were on the level, the main objective seems to have been to really just get the country back to normal as soon as possible. The courts figured out who had been collaborators and who had not, then those convicted were punished, mostly through internment in concentration camps, though some high-level figures faced the firing squad.

That should have been the end of it, and for a long time it was. The Dutch narrative focused on the heroics of the resistance (people like Willem Arondeus and Hannie Schaft featured prominently) and NSB became a curse word to describe the worst kind of person. This may have been correct, after all it included informers who had betrayed Jewish families for the price of two-and-a-half guilders per head, but it ignored the fact that it had been an awful lot of people that had collaborated.

Opening the archive

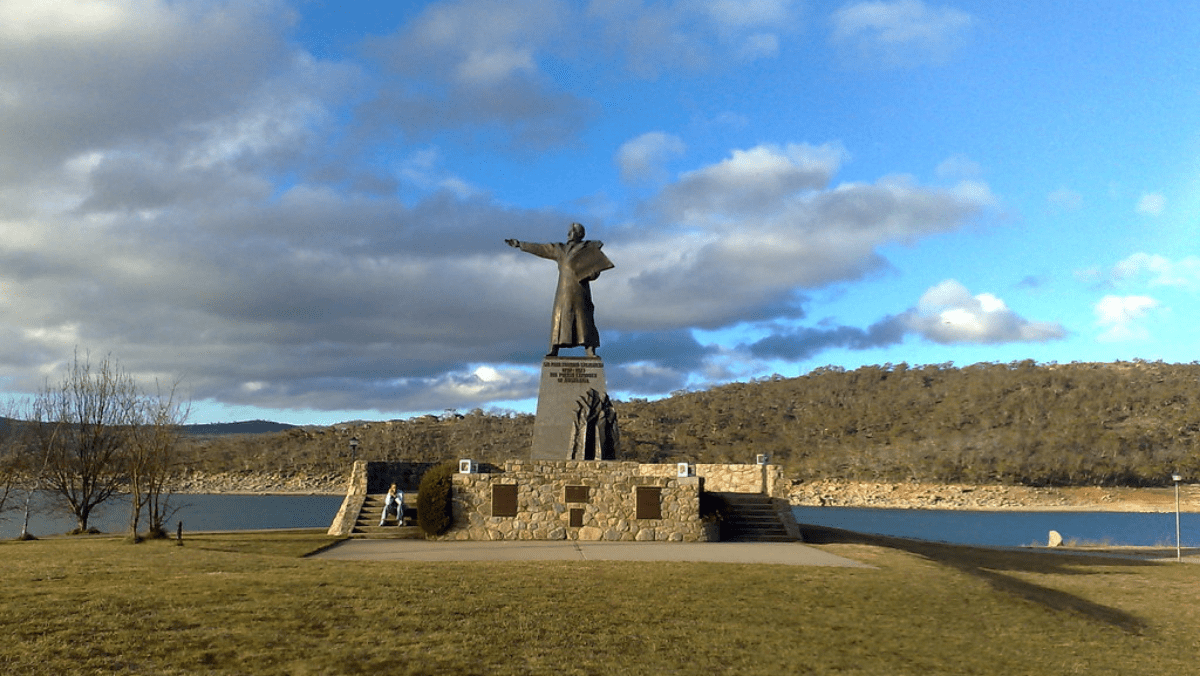

Over the years, the archives of the special legal proceedings (CABR, or Centraal Archief Bijzondere Rechtspleging) became an important source for anybody researching the wartime history of the Netherlands. It held the records of the legal proceedings of about 425.000 people who had been suspected of collaborating with the Germans in one way or the other.

However, it wasn’t freely accessible by everybody. For one, you needed a good reason to do so, you couldn’t rock up and start seeing if your neighbour’s granddad was on the lists. On top of that, since all the files were still only on paper, you also needed some pretty serious research skills to find what you needed, not to mention you needed to understand the language used — no mean feat since Dutch has changed a lot in the intervening years.

However, over the years the archive has been fully digitized, and it was decided that the full archive was to be made accessible to the public on January 2, 2025. From that date anybody could access the CABR and search for anything.

The Dutch privacy watchdog almost immediately warned against this, as did a number of academics. In all fairness, they had a point: as explained in this article, only about 20 percent of those who appeared before a special legal proceeding were actually convicted; the other 80 percent were either small fry, and there is a lot of evidence the proceedings were used to settle petty scores that had nothing to do with collaboration. Just because somebody’s name is in the archive doesn’t mean they did anything wrong.

However, even with a 100 percent conviction rate, you could ask yourself whether it’s necessary to hang out everybody’s dirty laundry. The fear is that because of the stigma of collaboration, grandchildren of a NSB member could be held accountable for the deeds of a person they may not even have known.

Interestingly, there is a much better example of how to handle issues like this which comes, somewhat ironically, from Germany. After the Wall fell, the massive archives of the Stasi, the East German state security police, were made accessible in a bid to heal wounds through transparency. Considering about one in ten of all East Germans was booked as an informer in some capacity, the possible repercussions were massive.

The Germans wisely decided to make it so the archives can only be accessed in person, and there is always staff present to assist in making sense of what’s found. It’s a great way of balancing openness with historical guidance.

It was also decided that it would be the way the CABR would handle things. After much back and forth in the media and parliament, full online access of the archives was cancelled. Instead, interested parties can book a place at the archive and view any and all materials there, both on paper and digitally. Making copies is not allowed, either, preserving the privacy of any records found. As important as history is, maybe sometimes we should also keep the present in mind.

Articles you may also like

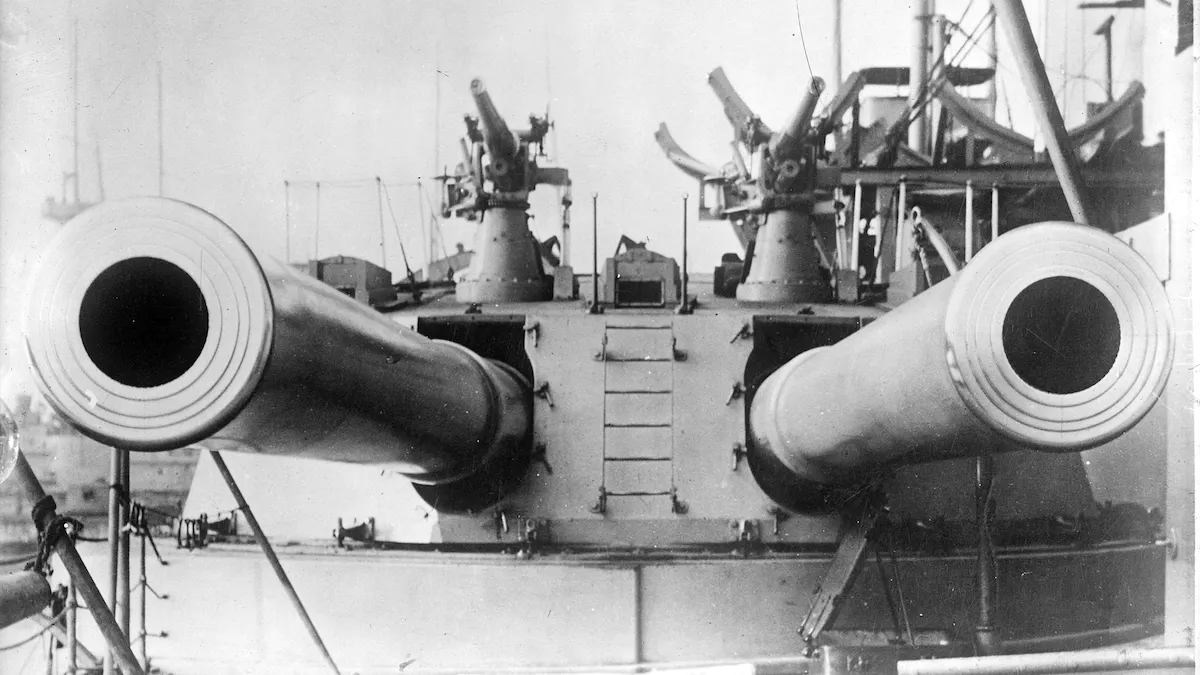

Maths swayed the Battle of Jutland – and helped Britain keep control of the seas

Reading time: 5 minutes

If you’re about to fight a battle, would you rather have a larger fleet, or a smaller but more advanced one? One hundred years ago, on May 31 1916, the British Royal Navy was about to find out if its choice of a larger fleet was the correct one. At the Battle of Jutland – as the major naval battle of World War I is known in English – these choices were unusually influenced by mathematics.

Weekly History Quiz No.245

1. Who was an Official Australian Photographer during both WWI and WWII, as well as accompanying three Antarctic Expeditions?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The Australians who Captured Rommel’s Intelligence Unit, Company 621

Reading time: 5 minutes

Though the North African campaigns of World War 2 have a reputation for mainly being fought by tanks, both sides relied as much on spying as they did on cold, hard steel. When the 9th Australian Division captured the German signals intelligence unit, company 621, right before the first battle of El Alamein, they dealt Field Marshal Erwin Rommel a fatal blow.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.