Reading time: 12 minutes

From 1939 to 1945, scarcely one of the 99 countries on Earth went untouched. Just 14 nations remained neutral throughout the Second World War, and even those couldn’t completely escape the gravity well of war.

By Morgan WR Dunn

Nor did they all want to. A prelude to the European war – bloody, massive, and unspeakably destructive – had played out in Spain from 1936 until just a few months before Germany invaded Poland in the fall of 1939.

When the Spanish Civil War ended, Spain was left in ruins, and with a fascist-sympathizing government with a deep hatred of the Soviet Union. So when Hitler needed volunteers for Operation Barbarossa, Francisco Franco delivered, sending 47,000 men to serve in the Blue Division. Men from this forgotten expeditionary force would fight for the Third Reich to the bitter end.

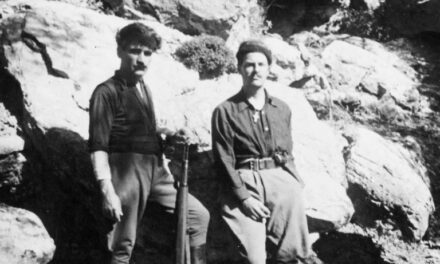

ROOTS OF THE BLUE DIVISION: THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR

Throughout the 20th century, as the last traces of empire ground to a halt in Spain, demand for long-overdue social and economic reform reached a crescendo. King Alfonso XIII had abandoned his throne in 1931, leaving the Second Spanish Republic to meet that demand. In February 1936, a left-wing dominated coalition, the Popular Front, came to power, exciting fear and fury in Spain’s Catholic, conservative ruling class.

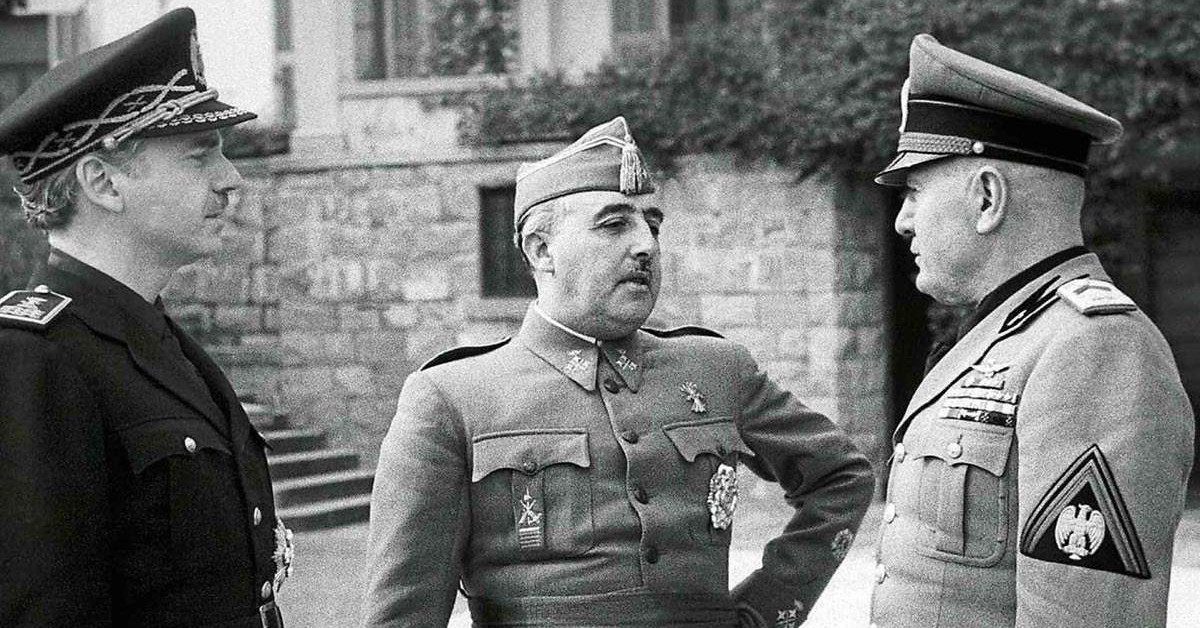

At the same time, a minor fascist political party, Falange Española de las JONS, or Falange, looked to Mussolini’s Italy and the rising star of Hitler’s Germany as a model for Spanish national rejuvenation. And in the Canary Islands, an exiled army general, Francisco Franco, saw an opportunity to reforge his country into the self-sufficient world power he thought it deserved to be.

In July 1936, Franco, having cast his lot with a group of conspirators within the Spanish military, flew to Morocco, executed 200 Republican officers, and assumed control of the 30,000-strong Army of Africa. Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy supplied aircraft to carry half this force to Andalusia. This would form the core of a Nationalist army which would carefully dismantle the Republic over the following three years.

Throughout the Spanish Civil War, the most active support for Franco’s Nationalists came from Germany and Italy. Both Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini provided ground and air forces, regular supplies of arms, ammunition, vehicles, and many millions in lira and marks.

It paid off: on 1 April 1939, Franco informed the Spanish nation that “Today, with the Red Army captive and disarmed, the national troops have achieved their last military objectives. The war is over.”

Spain’s Civil War left half a million dead, as many refugees, and the already frail economy in tatters. Republican guerrillas carried on resisting in the countryside or staged raids from France. And just a few months later, German forces blitzed across their eastern border into Poland, igniting a new war which would consume them.

SPANISH POLITICS AND THE GERMAN ALLIANCE

Between the Fall of France and the invasion of the Soviet Union, Spain was strongly tempted to join the Axis powers. Hitler had even met with Franco, hoping to persuade him to ally with Germany at the French border town of Hendaye in October 1940. Franco, however, demanded Gibraltar, France’s North African territories, and a vast economic reconstruction package in return.

It was too high a price for Hitler, who supposedly told Mussolini afterward that he would rather “have three or four teeth pulled” than negotiate with Franco again. Moreover, the Spanish public felt they had no quarrel with Britain or its allies.

Communism was a different matter. The Soviet Union had been the only major power to support the Republic during the Civil War, and Franco’s Spain was eager for revenge.

So when, in June 1941, news reached Madrid that the German military had invaded the USSR, the Falange immediately began agitating for Spain to contribute. The first to make his move was Ramón Serrano Suñer, Spain’s Falangist foreign minister and Franco’s brother-in-law.

Serrano hoped to form a “unit of volunteers against Bolshevism” composed entirely of Falangist militiamen, or “Blueshirts.” Spanish Army leaders agreed, but refused to entertain the idea of a unit under Falangist control.

Franco, a career soldier himself, backed the generals, but offered a compromise. Falangists could volunteer alongside regular soldiers and Civil War veterans, but the unit would be commanded by the Falangist-sympathizing army general Agustín Muñoz Grandes. As long as Spanish volunteers only fought on the Eastern Front, Franco reasoned, he could keep Spain out of the wider war.

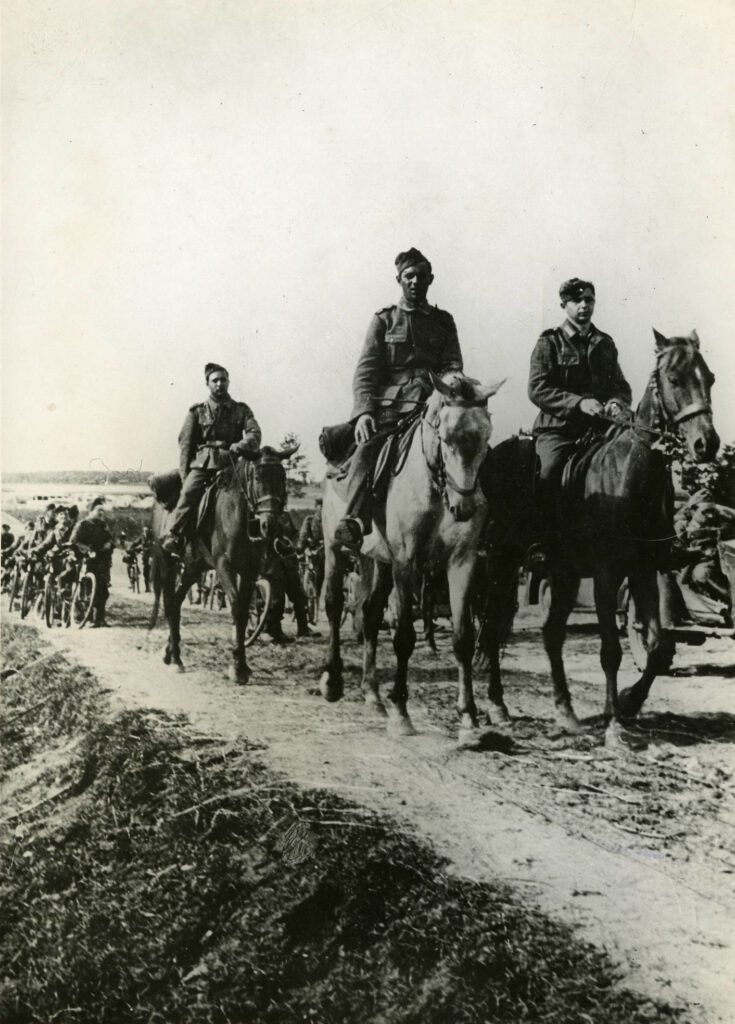

Operation Barbarossa began on 22 June. Within two weeks, 18,000 men had enlisted in the Spanish Volunteer, or Blue, Division, so-called for the Falangist uniform of a blue shirt paired with a red monarchist beret. So many had joined so quickly that thousands of volunteers had to be placed on a waiting list. The newly-enrolled division, meanwhile, made its way to Bavaria for training.

BLUE DIVISION ON THE FRONT

The Spanish volunteers were welcomed with rapturous applause in Germany. On 31 July, they were integrated into the Wehrmacht as the 250th Infantry Division with this unusual oath:

“Do you swear before God and your honor as Spaniards absolute obedience to Adolf Hitler, leader of the German army, in the fight against communism and do you swear to fight as brave soldiers ready to give your lives at any moment to obey this oath?”

Given the rapid successes the Germans had seen all over Europe, the newcomers worried that the war in Russia would be over before they could get there. Muñoz Grandes found a way to shorten the six-month training program to less than one month by claiming that all of his men, now equipped with German weapons and uniforms, were veterans of the Civil War.

From the beginning, the Spanish Volunteer Division stood out from its German allies. One officer reported to Field Marshal Fedor von Bock that:

“Rifles are often sold. New bicycles are thrown away as they find tire repair too boring. The MG- 34 is often assembled with the help of a hammer. Parts left over during assembly are buried.”

German Liaison Officer to the Spanish Division

Neither would the Blue Division, subject only to Spanish military law, imitate German atrocities. “Reprisals, hostage taking, and exactions from civilians, common in the Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS, were forbidden.”

Spanish military hospitals sheltered “educated Poles, Lithuanians, Latvians, Russians, and Jews from the Nazis,” and “the divisional general staff had to keep reminding the troops not to free Soviet prisoners of war.” The Spanish habit of freeing female Soviet POWs was particularly annoying to the Germans.

German instructors were unimpressed with the Spaniards’ military bearing, but the volunteers quickly proved to be ferocious on the battlefield. After marching nearly 600 miles from Suwalki in occupied Poland, they took charge of a 50-kilometer sector between Leningrad and Moscow in October 1941. The Blue Division would spend the winter of 1941-42 in grinding trench warfare.

The cold and the constant danger took a toll, inflicting 7,000 casualties on the division. To keep up morale, Franco sent shipments of Spanish food, tobacco, alcohol, and coffee that Christmas. Along with the trainload of goods came a second batch of volunteers, this time mostly regular soldiers to replace the Falangist enthusiasts and students who’d gone first.

LEAVING THE NEW ORDER

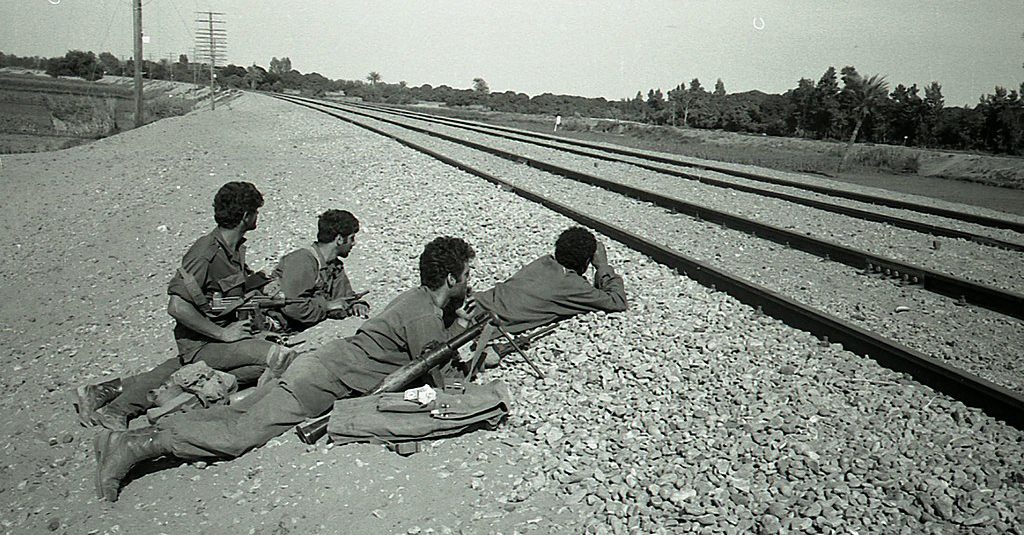

From 1942 to 1943, Soviet resistance began to pay off. For most of its time on the Eastern Front, the Blue Division had stayed out of major battles. But now, frantically fighting to salvage Hitler’s conquest, the Germans needed every soldier they could get.

By the time it was drawn into the fighting around Leningrad, the Blue Division, by now under the command of Emilio Esteban Infantes, was just as experienced and hardened as its German counterparts. Hitler himself once said that “one can’t imagine more fearless fellows. They scarcely take cover. They flout death.”

At peak strength due to constant reinforcements, the division was an ideal unit to secure the Moscow-Leningrad highway. But that also placed it directly in the path of the latest Soviet attempt to relieve Leningrad on February 10, 1943.

That morning, a three-hour artillery barrage, 44,000 Soviet troops, and 100 tanks, including 50-ton KV-1 heavy tanks, launched a blistering 24-hour assault on just 5,600 Blue Division soldiers. The Spanish troops managed to inflict 11,000 casualties, but at a heavy cost. On February 1, the Blue Division had numbered 15,867 men. A month later, Soviet actions had worn it down to 12,464 – after reinforcements had arrived.

The war was turning against the Axis. Franco, as an officially neutral leader, had to adapt to the increasingly obvious fact that the Allies were going to win. On 29 July 1943, the US ambassador in Madrid demanded the repatriation of the Blue Division.

That September, he agreed, and made an official request to Berlin for the dismissal of the Spanish volunteers from the Eastern Front. The last members of the disbanded Blue Division reached Spain in December 1943.

Not all the volunteers wanted to leave, though. Some 1,500 were left behind to form the Blue Legion. Members of this regiment-sized unit were told they would remain at the front without relief or reinforcements, until “its extinction in combat.” Joining them were hundreds of Spanish men who crossed the Pyrenees on foot until the Allies liberated France.

Even these units were disbanded by the spring of 1944. Yet still Spanish soldiers stayed on, illegally enlisting in the Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS. These final holdouts were thrown into the fray wherever Nazi Germany was collapsing, including the final battle for Berlin itself.

LEGACY OF THE BLUE DIVISION

From 1941 until the last official volunteers came home in 1944, 47,000 Spanish soldiers and volunteers had passed through the ranks of the Blue Division and the Blue Legion.

4,500 had died, 8,000 had been wounded, and the medical staff recorded 7,800 cases of illness and 1,600 of frostbite in the bitter Russian winters. The Red Army captured 464 Spanish soldiers between 1941 and 1945, of whom about 70 were deserters.

Germany’s crushing defeat forced Franco to desperately make every effort to reconcile with the Allies. Downed Allied airmen were treated well and allowed to leave, and fleeing Nazi officers and leaders were barred from seeking refuge in Spain.

It wasn’t enough to undo Spain’s lengthy record of support for Germany. The Blue Division was effectively struck from public memory, any mention of Spain’s contribution to the invasion of the USSR becoming taboo. When Ramón Serrano Suñer published his memoirs of the period, he never once mentioned the unit which had been his idea to begin with.

When the war ended, the United States, United Kingdom, and France withdrew their ambassadors from Madrid. Spain was not allowed to join the United Nations until 1955. Blue Division veterans’ groups became active for a time. But as the Cold War unfolded, Franco silenced these while he sought to capitalize on his anti-communist credentials.

The last living member of the division, Arturo de Gregorio, died at the age of 102 in September 2023. It had been almost exactly 80 years after the division began its exodus from Hitler’s nightmarish Russian war. As the years passed and the old soldiers of the Spanish Volunteer Division died out, the few survivors took to requesting that their obituaries contain a simple phrase: “Veteran of the Blue Division.”

Podcasts about the Spanish Blue Division

Articles you may also like

The A.E.F.: With General Pershing and the American Forces – Audiobook

THE A.E.F.: WITH GENERAL PERSHING AND THE AMERICAN FORCES – AUDIOBOOK By Heywood Broun (1888 – 1939) In 1917, the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) arrived in Europe to fight alongside the French and British allied forces. American journalist Heywood Broun followed the AEF and reported on their experiences. He published these sketches in book form in […]

What happened to the French army after Dunkirk

Reading time: 5 minutes

The evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in May 1940 from Dunkirk by a flotilla of small ships has entered British folklore. Dunkirk, a new action film by director Christopher Nolan, depicts the events from land, sea and air and has revived awe for the plucky courage of those involved.

General History Quiz 185

1. When did the Yom Kippur War begin?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.