Reading time: 7 minutes

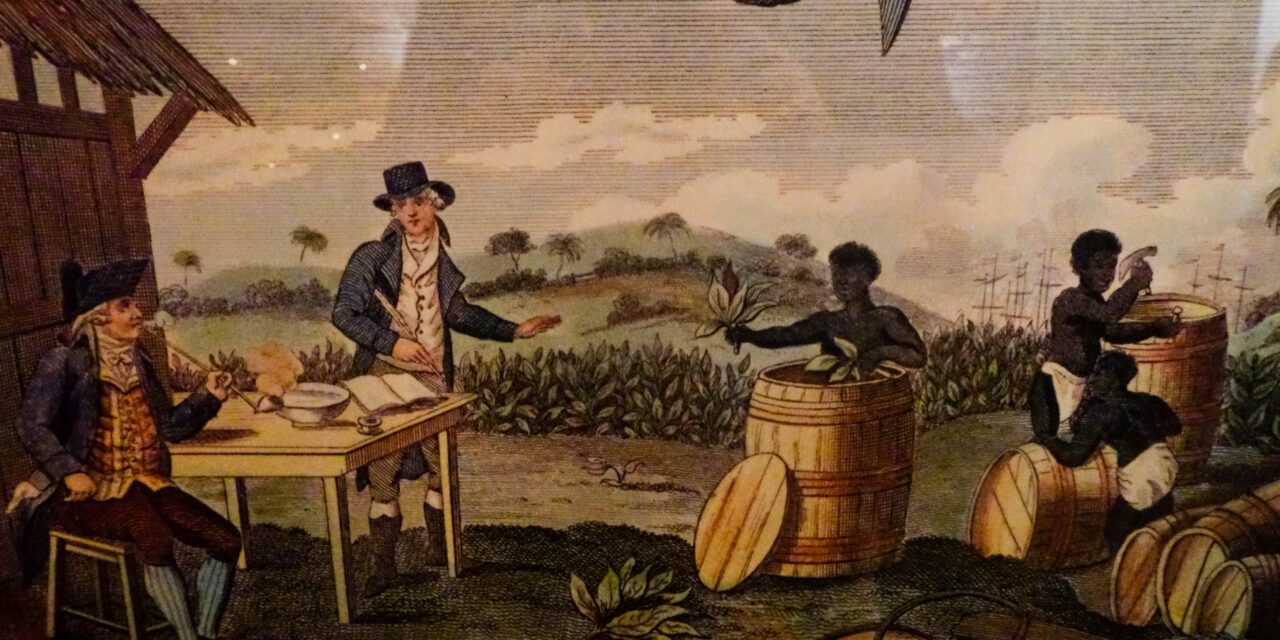

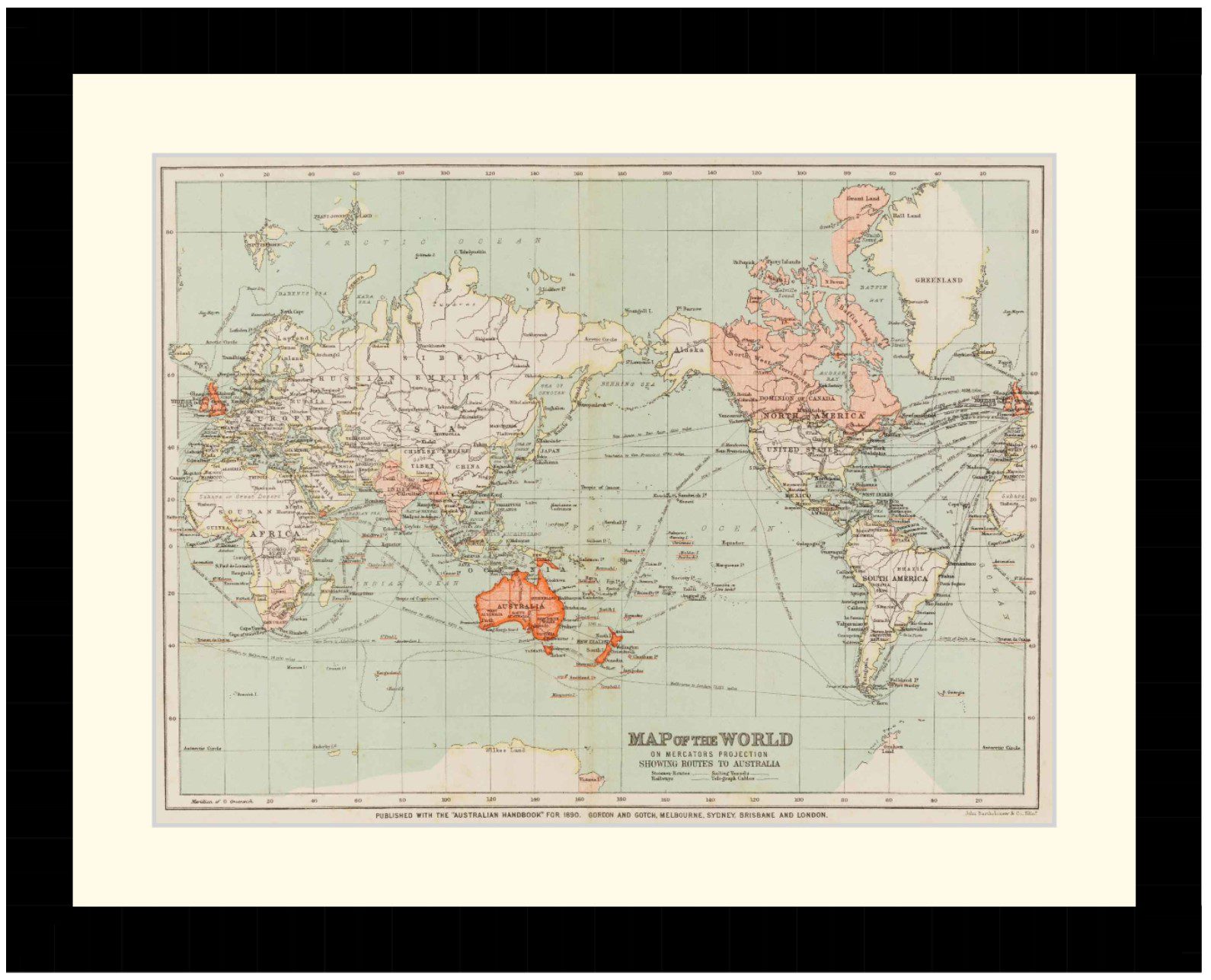

By the 1730s, Britain was the largest slave-trading Empire in the world. It is estimated that between 1640 and 1800, private British citizens across the Empire transported 3.1 million Africans as slaves.

Yet less than seven years later, the British parliament officially abolished slavery. And they didn’t stop there. The British government then proceeded to pressure allies and other European nations such as Portugal, Spain and France to also abolish slavery, and devoted significant Royal Navy resources to intercept and arrest slaving ships off the coast of Africa.

So what changed?

By Mark McKenzie

The Rise of The Abolition Movement

The default answer is Britain had a change of heart. Of course, as with most things in history, the truth is a little more complicated than this. Morals not the only factor in abolition, it is also always important to remember that nations have no “single” ideology.

Many different groups of people played a significant role in campaigning for the British government to outlaw and abolish slavery across the Empire.

Quakers, women such as Elizabeth Heyrick, and Christian philanthropists all played critical roles in the early abolitionist movement.

The legal position of slaves in Great Britain was decided in the case of Somerset vs Stewart in 1772, in which abolitionist Granville Sharp successfully argued that someone could not be held as a slave within Great Britain. This did not apply to the British colonies though. To stop the trade, the British parliament would need to be convinced to ban it.

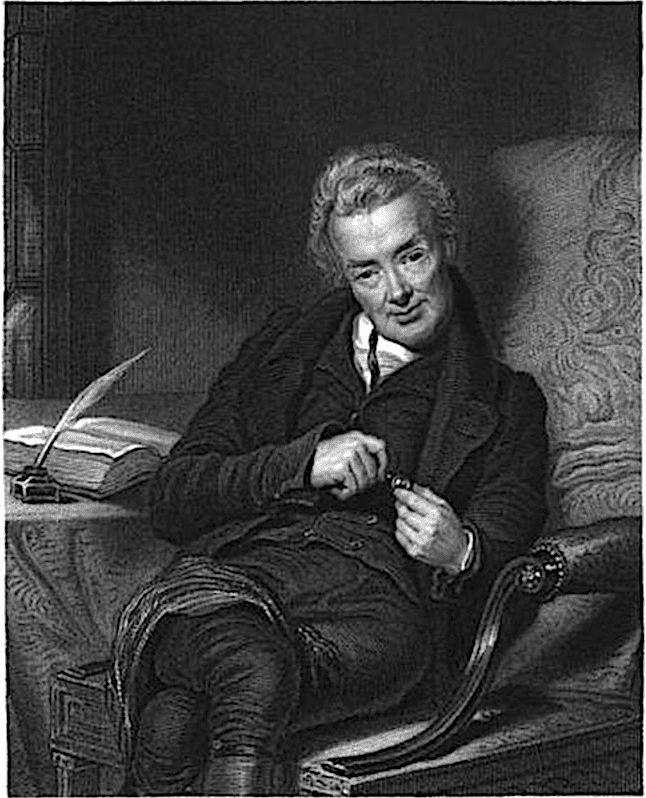

The first dam broke in 1807, when the abolitionist movement led by William Wilberforce convinced parliament to pass the Slave Trade Act, banning the trading of slaves, but not slavery itself.

Only in 1834 did the Slavery Abolition Act completely outlaw the practice of slavery across the Empire.

Money Always Wins

As much as it would be nice to think abolition was built entirely on good-hearted morality, money always plays a role.

The abolition of the slave trade coincided with Britain’s (and the world’s) Industrial Revolution, and just as pro-slavery politicians had vested economic interests in slavery, so did many other abolitionist lobbying groups who had economic interests in the end of slavery.

Cities such as Liverpool had smaller abolition movements due to their links to the slave trade, with one in eight Liverpool families being reliant on the slave trade in 1790. On the flip side, industrial cities such as Birmingham and Manchester offered much less support for slavery, as the people in those cities did not rely on the trade to survive.

In 1789, Liverpool submitted 12 petitions to parliament to attempt to block the abolition of slavery, while other cities such as Lancaster, Bristol, and Birmingham sent only one.

Once again it is important to remember that these are millions of people, and one single voice cannot be taken from the group, either from a pro-abolition city like Birmingham, which still sent one petition, or a pro-slavery city like Liverpool, which still had its own abolition movement.

We can, however, identify just how important the economy of a place was in determining abolitionist sympathies. At the end of the day, money talks, and the industrial revolution gave many working-class families the agency to support abolition, through the virtue of not being reliant on slavery.

The same can be said for the aristocracy – some of the most prominent pro-slavery politicians such as former Prime Minister Gladstone had vast family wealth tied to the slave trade. In contrast, abolitionists had family wealth from other means such as William Wilberforce and the Baltic trade.

Despite Britain’s great achievement, the sad fact is it was the slavers, not the slaves themselves, who were compensated under the 1834 abolition, at the cost of the taxpayer – the general public of Britain.

Protecting Britain’s Strategic Interests

Not everyone in Parliament supported abolition, and many resisted. However, it became clear that enforcing a global ban on the slave trade could work in Britain’s interest.

Movements such as Elizabeth Heyrick’s consumer boycott of West Indies slave sugar didn’t always abandon the good (in this case sugar), but instead chose to buy sugar from the East Indies where the sugar was not harvested by slaves. The sugar was still sold, however, by British companies!

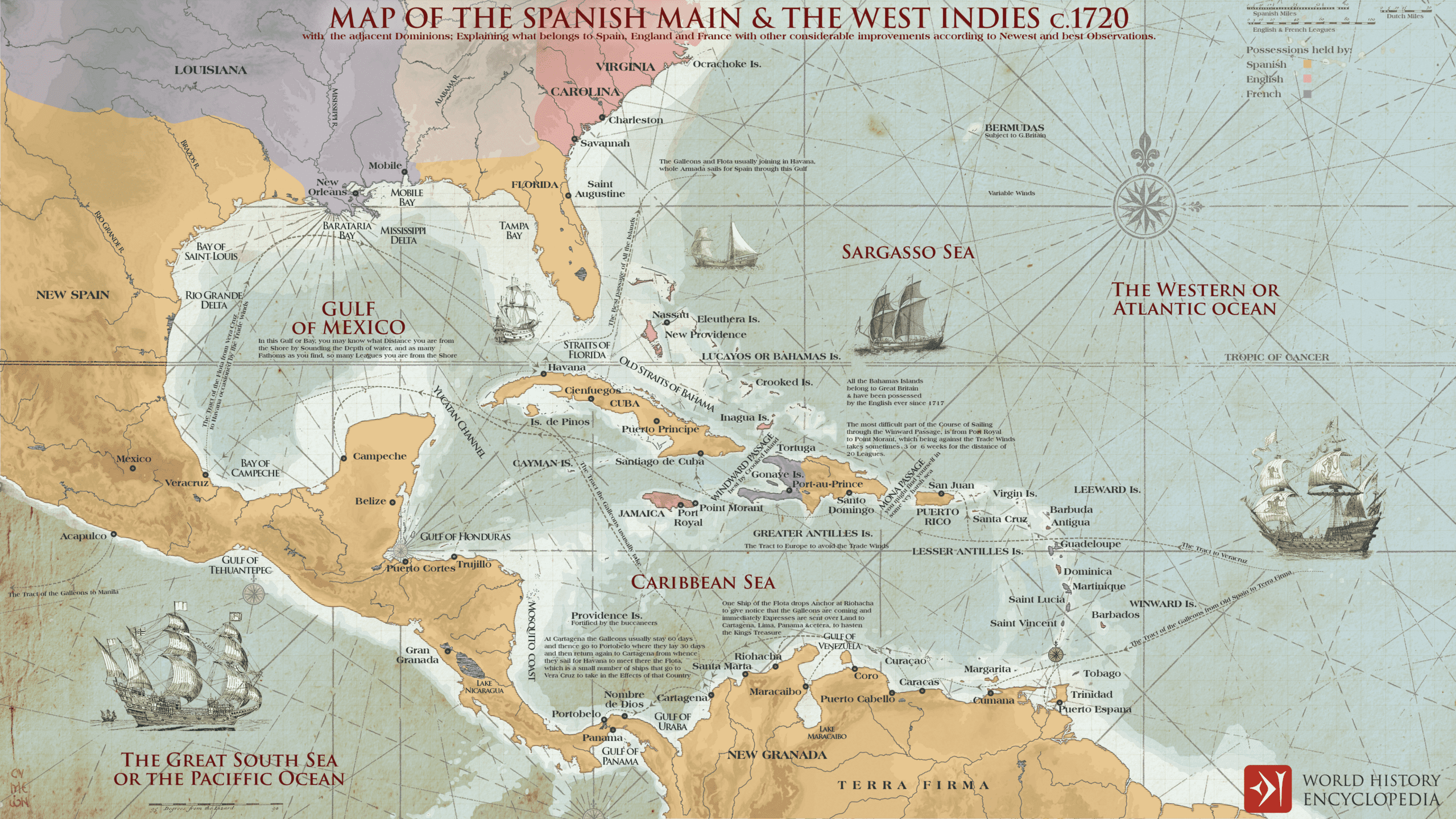

While Britain was the first major power to industrialise, its major allies and enemies were much slower to do so – where the British Empire was well on the way to fully industrializing in the early 1800s, the French would take another 50 years to catch up. The Spanish? A further 100 years.

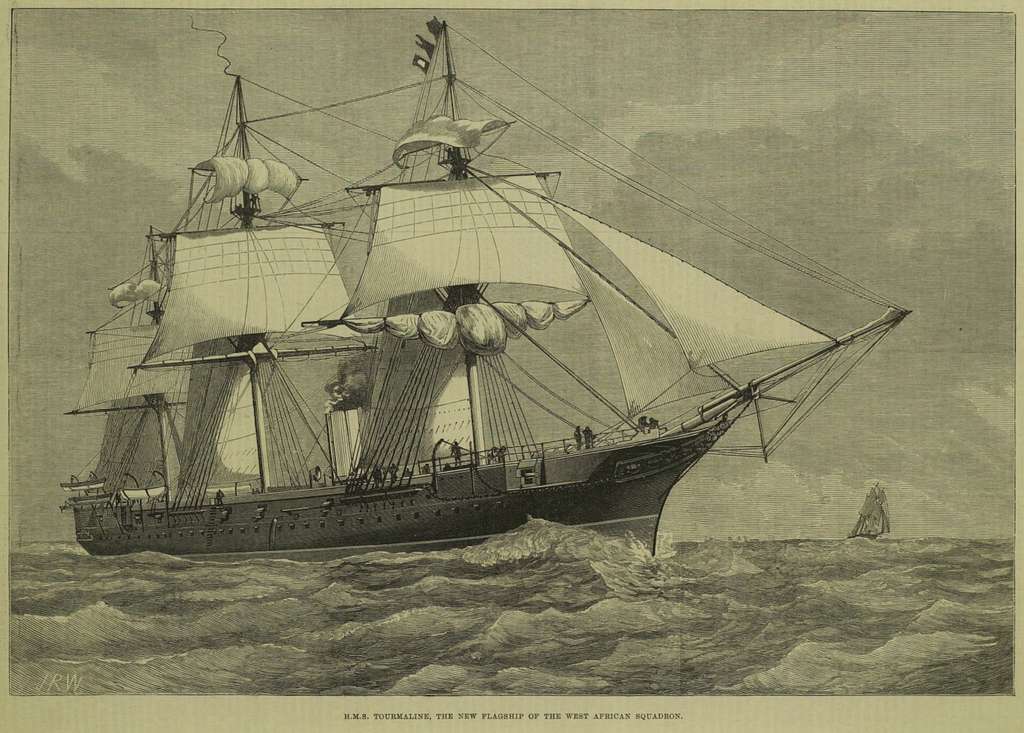

Upon the abolition of slavery, the British Royal Navy created the West Africa Squadron, a fleet of ships dedicated to patrolling West Africa, apprehending slaving vessels, and freeing slaves.

Of course, many of the ships intercepted were French or Spanish. In one moral victory, Britain successfully kneecapped a major economic artery of two of its biggest rivals, while Britain herself had already moved on from being economically reliant on the slave trade.

There’s no record of clandestine meetings discussing the political advantage of abolition. Likely, there weren’t any at all, and that this was not a conscious effort or decision from the British government.

Despite this, it’s clear that this political factor was yet another subtle factor that may have encouraged British MPs to vote in favour of abolition in 1834, knowing soundly that they would not be endangering the Empire in doing so.

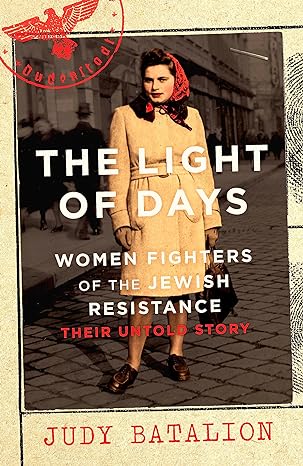

Was Abolition Really Based on Money and Politics, Not Morality?

Yes, but not in the way you may think. While as historians we cannot claim to see into the minds of every abolitionist in Britain, evidence such as the private notes of Granville Sharp, local fundraisers, and the actions of people such as William Fox and Martha Gurney the abolitionist pamphleteers suggest that they did indeed oppose slavery because of a strong moral compass.

However, their success was very much influenced by wealth, power, and the political interests of other aristocrats within the Empire. Had William Wilberforce’s wealth derived from slavery just as Gladstone’s, perhaps he would not have campaigned for abolition.

The idea of freedom and liberty had long been a fundamental part of English and British law, and from the 1700s to abolition in 1807, the intellectual class, aristocracy, and working class of mainland Britain began to gradually apply these ideas to the practices of slavery carried out away from the island.

Moral virtues, alongside economic alternatives and political advantage all played key roles in Britain’s sudden social and political change that saw a 180o turn on slavery across just two generations.

Articles you may also like

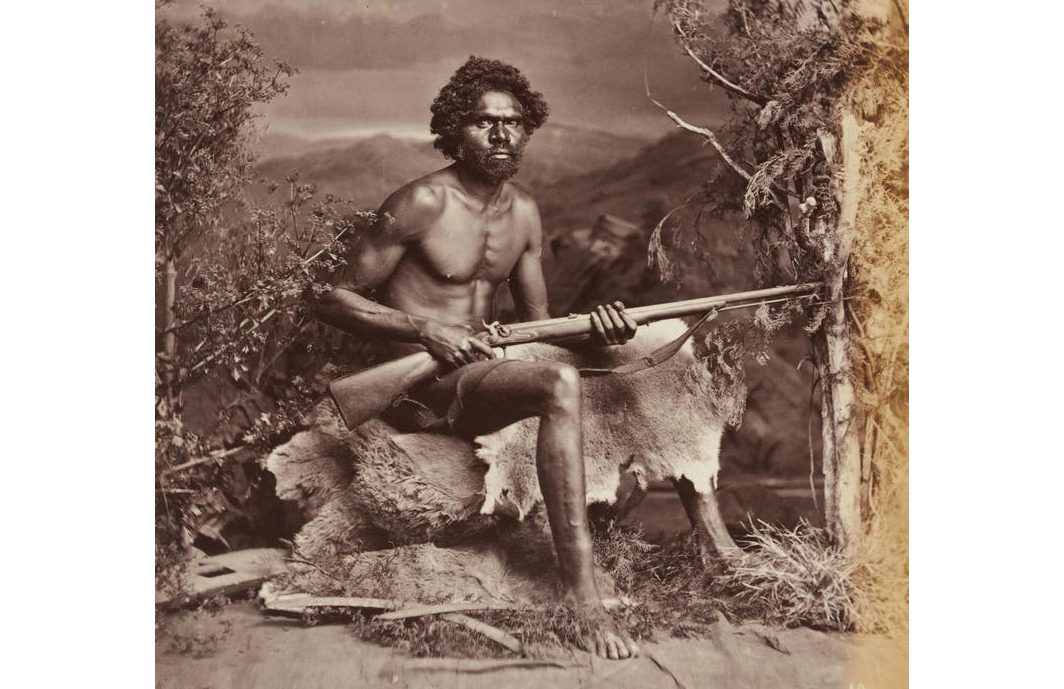

It’s time for a new museum dedicated to the fighters of the frontier wars

Historical research of the last 20 years has confirmed the central importance of the killing times. They lasted far longer and were much more deadly than generations of Australians were led to believe. For many years the truth was either deftly avoided or consciously suppressed. Aboriginal families kept alive their own memories of those terrible […]

General History Quiz 148

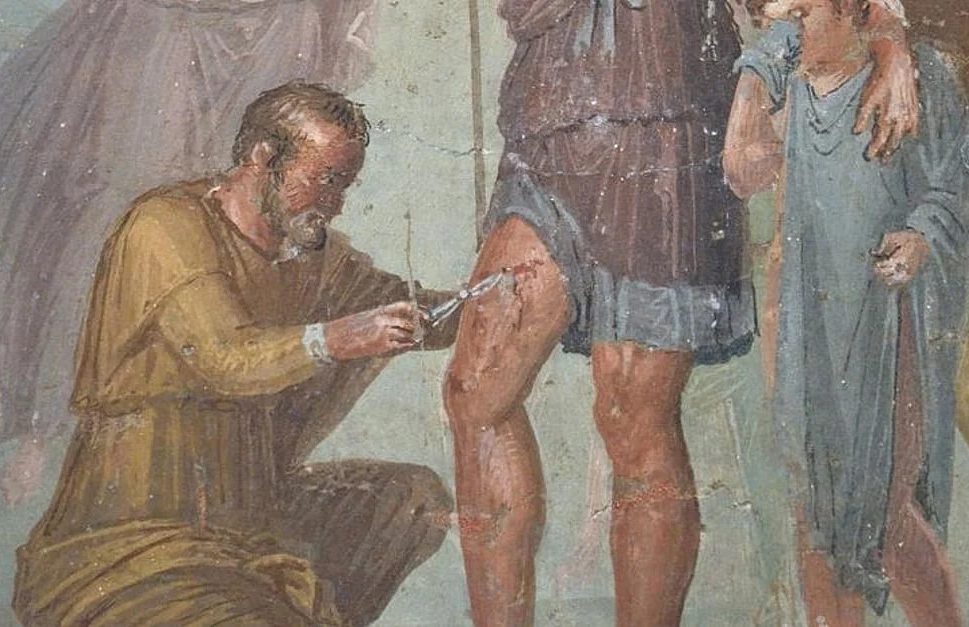

1. Who said “War is the only proper school for a surgeon.”?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.