Reading time: 13 minutes

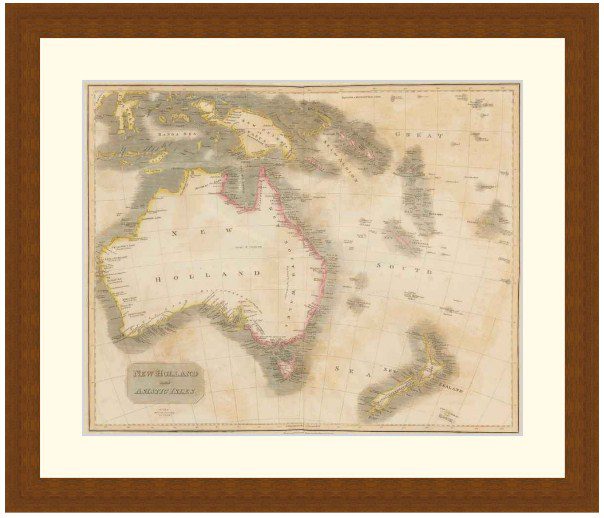

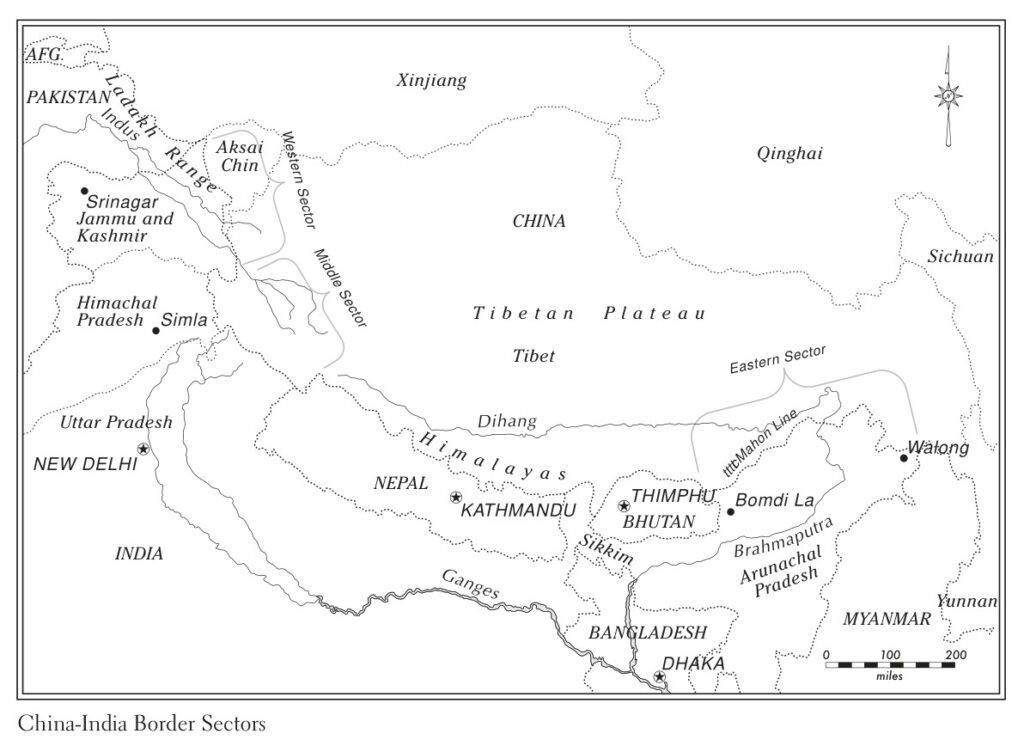

There are corners of the map where the neat lines of national boundaries, so carefully laid and plotted over the modern era, begin to blur and bleed. Aksai Chin, the bleak “White Stone Desert” which sits just inside China’s western border, is one of these.

By Morgan W. R. Dunn

A tangled mix of colonial border legacies, Cold War politics, and growing militarism, under intense pressure from rival states in a tense era of world history, finally exploded in 1962. In October of that year, Chinese forces rushed across the pale desert, setting off the Sino-Indian War. After just a month of fighting, thousands lay dead and the frontier between two emerging powers had shifted – a border dispute which is, to this day, unresolved.

A Border Conflict is Born

The conflict over Aksai Chin was not started by either China or India. It arose as a consequence of the “Great Game,” a 19th century contest between Britain and Russia for Central Asian territory and influence. Russia, hungry for land, was poised to clash with the borders of British India. A tense Raj had reason to delineate the Russian, Chinese, and Indian boundaries where they met in the Pamir Mountains.

“Aksai Chin,” wrote the American historian Robert Huttenback, “was such a remote area during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that … reports frequently differed even about its location. In 1896, the British agent in Kashgar admitted that the “Aksai Chin was a general name for an ill-defined and very elevated table land at the north-east of Ladakh and it was probably the case that part was in Chinese and part in British territory.””

The region had no arable land, little water, no rivers, and few inhabitants. But it did contain the only all-weather route to Xinjiang in the north, and it lay within the territory of Tibet. In 1924, Sir Charles Bell, a British official with strong connections to the mountain kingdom, wrote:

“We want Tibet as a buffer to India on the north. Now there are buffers and buffers; and some of them are of very little use. But Tibet is ideal in this respect. With the large desolate area of the Northern Plains controlled by the Lhasa Government, central and southern Tibet governed by the same authority, and the Himalayan border States guided by, or in close alliance with, the British-Indian Government, Tibet forms a barrier equal, or superior, to anything that the world can show elsewhere.”

Over the following decades, the border would be drawn and redrawn as tensions over the border simmered. Finally, amid Chinese efforts to take advantage of Britain’s distraction by war with Germany in 1914, British Indian foreign secretary Henry McMahon agreed on a boundary, afterward known as the McMahon Line, with Tibet. China was not involved in the discussion.

Rising Tensions in the Himalayas

A convoluted history of colonial wrangling had rendered Aksai Chin a contested no-man’s-land high in the Himalayas. In October 1949, the People’s Republic of China was established. In January of the following year, India became a republic. Each inherited a wealth of problems from their imperial predecessors.

The People’s Republic laid claim to the old boundaries of the Qing dynasty, under which China had reached its greatest territorial extent. Until 1912, when the Qing was overthrown and replaced with the Republic of China, that had included Tibet. India laid claim to a slightly older border, encompassing the Ladakh region conquered by the Sikh Empire in the 1840s, which then became part of British territory when East India Company forces conquered that empire in 1846.

By 1954, long-time Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru ruled that the McMahon Line “should be considered a firm and definite” border. But a few years earlier, the People’s Republic of China had conquered the old Qing imperial possession of Tibet, whose territory, from their point of view, encompassed Aksai Chin.

The new expanse of Chinese territory caused anxiety on both sides of the Himalayas. For the first time in history, China and India shared a border without Tibet acting as a buffer. Indian leaders saw what was evidently an aggressive China, ready to flex military muscle built up over decades to pursue its aims.

That same military might was used to ruthlessly crush unrest in Tibet. When protests in Lhasa erupted into a full-blown revolt in 1959, the 14th Dalai Lama was given sanctuary in India. He was given a lavish reception, and Nehru paid an official visit to him upon his arrival. Beijing saw this as a violation of Indian promises not to allow the Dalai Lama to engage in anti-Chinese political activity and a possible sign of Indian designs on Tibet. Already, conflict was brewing. “When the time comes,” reflected one-day Chinese premier Deng Xiaoping in 1959, “we certainly will settle accounts with them.”

The Evil Day of Reckoning

Long-simmering tension began to tell at the border. Since the summer of 1961, Indian military leaders had pursued what was later called the “forward policy,” involving the establishment of military posts to safeguard territory they regarded as forming part of the North East Frontier Agency (NEFA). Among the provocations was the construction of a Chinese road linking Tibet and Xinjiang which crossed the old pre-McMahon border known as the Johnson Line in several places.

Throughout September, Chinese People’s Liberation Army and Indian Army troops bristled at one another and jostled for position. Finally, on the morning of 20 October – what Brigadier John Dalvi of the 7th Indian Brigade called “the evil day of reckoning” – PLA forces opened fire with over 150 mortars and artillery pieces while Chinese infantry rushed to dislodge Indian units from their outposts.

Chinese forces had prepared thoroughly, with officers infiltrating the border regions and pumping a network of informants for valuable data. The night before the attack, they cut Indian telephone lines and occupied high ground overlooking Indian outposts, allowing them to wipe out Indian artillery in the area. The Chinese, according to Dalvi, claimed that “the aggressive Indian forces … launched massive attacks against the Chinese Frontier Guards all along the Kachileng River and in the Khenzemane Area.”

Within a few hours, 10,000 PLA soldiers had captured or killed the Indians in the Namka Chu valley and captured Brigadier Dalvi. Within four days, Chinese troops had soundly beaten back Indian forces and occupied territory that was unquestionably India’s.

Now with the upper hand, Chinese leaders sought a settlement from Nehru.

Chinese Arms Ascendant

The People’s Liberation Army, 80,000-strong, had won resounding victories on the eastern front at Ladakh and the western at Aksai Chin. The Indians had inflicted severe casualties on the Chinese but, underprepared and outnumbered nearly four to one, they had been forced back from their forward positions and left winded and battered. On the eastern front, PLA troops had made a lightning-quick advance from Bum La Pass to take the major town of Tawang by 25 October. In the NEFA, they penetrated 100 miles south of the McMahon Line.

On 24 October, the Chinese government, through Premier Zhou Enlai, proposed a mutual withdrawal and to reopen negotiations. Since it required both armies to withdraw 12 miles either side of the line of actual control (LAC) – the de facto border – Nehru rejected the suggestion. Fighting resumed after a short pause.

The respite, while doubtless welcome to weary Indian troops, gave them no advantage when the battles continued. In the east, Chinese forces lunged at the town of Walong in Arunachal Pradesh state, taking the town with a five-to-one advantage in numbers while taking over 700 casualties. Over 650 Indians were killed and wounded and more than 300 taken prisoner. The Chinese also won victories at the Sela Pass and captured the town of Bomdila on 19 November.

At the time of its capture, a correspondent for the British Daily Telegraph noted that

“The fall of Bomdila means that the Chinese forces… have covered some 90 miles… in a [three-day] advance. It has taken the Chinese less than a month to push a road through from Bum La pass on the McMahon Line to Towang, bring up artillery and heavy 120mm mortars, and organize for a two-pronged offensive. This is a prodigious feat as, although Towang is only 12 miles from the old frontier as the crow flies, the terrain is ridged with ranges running up to 17,000 ft. The Indians had dug themselves in and brought up 25-pounders to secure the Se La positions. But when the Chinese hit them frontally… a few miles beyond Towang they were, according to the New Delhi spokesman, faced with overwhelming superiority in numbers and weapons.”

In the NEFA, Indian forces suffered a defeat at Gurung Hill. At Rezang La, on 18 November, Chinese forces were victorious again, this time in sight of the plains of Assam and thus deep in India’s North East Region (NER). Only fierce resistance from the Indian Army’s Kumaon Regiment checked the advance. At last, after just a month, with over 7,000 Indians dead, wounded, or captured and over 2,400 Chinese dead and wounded, the fighting slowed to a halt.

An Unresolved Fight

The Sino-Indian War of 1962 ended in victory for China. On 19 November, having broken India’s defense in the NEFA and NER, Chinese forces were ordered to cease fire and, from 21 November, withdraw 12 miles behind the line of actual control “as on November 7 1959.”

Chinese leaders did not give an explicit reason for the sudden ceasefire. A correspondent writing for the British paper The Times commented that the decision “appears at first sight to be a triumph of political expediency over military opportunism,” “taken when the momentum of attack was at its heaviest.”

“One interpretation is that they have succeeded in their main aim of demonstrating to the Indian Government and to the world that they are able to make any border adjustments which they may think necessary whenever they think fit, and that they can now retire to conduct negotiations from strength. The other main possibility is that pressure from Moscow, or some bargain with the Soviet Government, has been the deciding factor.”

The Chinese attack was launched in the midst of the Cuban Missile Crisis, and it has long been speculated that they intended to take advantage of the world’s preoccupation to achieve limited war aims. With the end of the crisis and no further objectives to achieve, extending the war risked destabilising the Himalayan frontier or drawing other major powers into a conflict which China, in all likelihood, could not have afforded to prolong.

For Mao Zedong, the war had been an invaluable distraction. 1962 saw the end of his Great Leap Forward, a disastrous and ill-planned industrialisation programme, and followed the loss of tens of millions of lives in the Great Chinese Famine. “In January [1962],” wrote Mao’s physician Dr. Li Zhisui, “[Mao’s] support within the party was at its lowest.” Having stepped down as president in 1959, Mao remained Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, and victory over India proved to be a critical step in his path back to uncontested leadership in the People’s Republic.

The effect on India was immense. The Defence Minister, V. K. Krishna Menon, fresh from the successful seizure of Portuguese India the year before, was forced to resign on 31 October over outrage at India’s military unpreparedness. The Chief of the Army Staff, Pran Nath Thapar, also resigned, on 19 November.

The loss also greatly affected Nehru. Already suffering from declining health in 1962, after the defeat in the Himalayas, Nehru felt dejected and humiliated. 20 months after the war, on 27 May 1964, he died at the age of 74 after nearly 17 years in power. “Without a Nehru,” wrote Brigadier Dalvi in his book on the 1962 war, “India ceased to be the moral leader of the non-aligned world. Whereas prior to 1962 she wielded immense power and influence despite her poverty and lack of military power, after the Chinese attack she was ‘cut to size’ in the words of one unfriendly critic of Nehru.”

To the present day, the India-China border has remained effectively where it stood on 21 November 1962. The two nations would clash again and again over the border over the years, although never to the terrible extent that the fighting went in 1962.

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 136

1. What did the first urban civilisations all have in common?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.