Reading time: 6 minutes

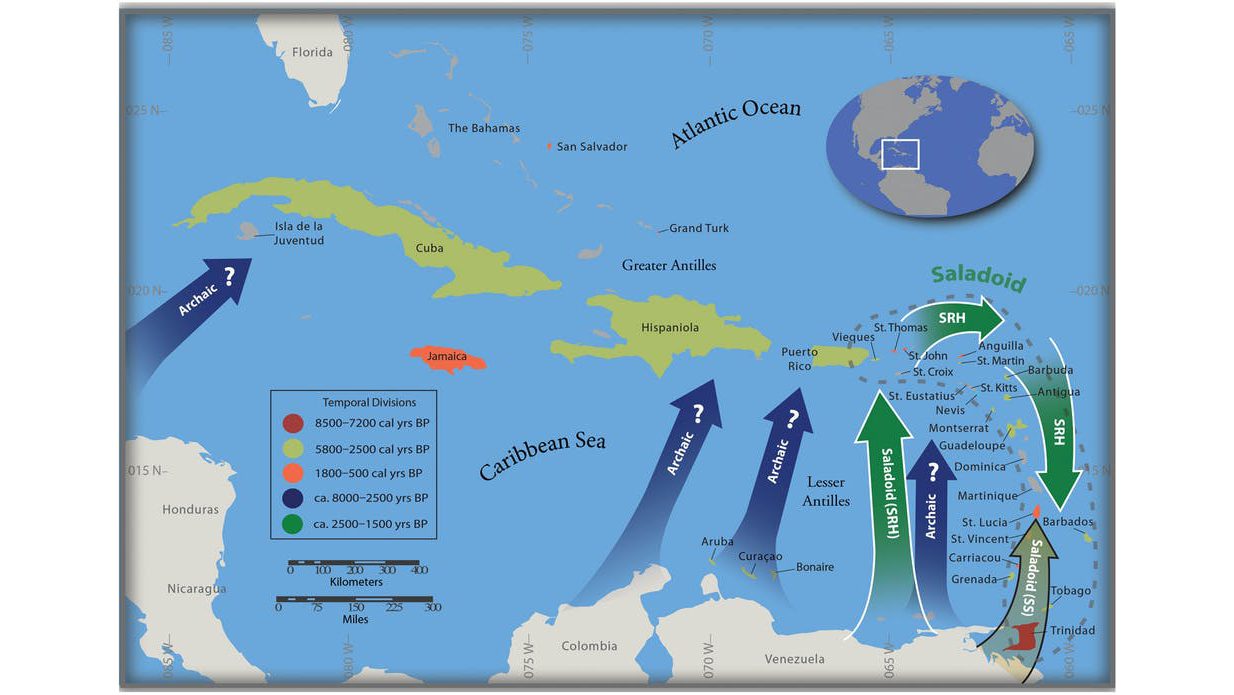

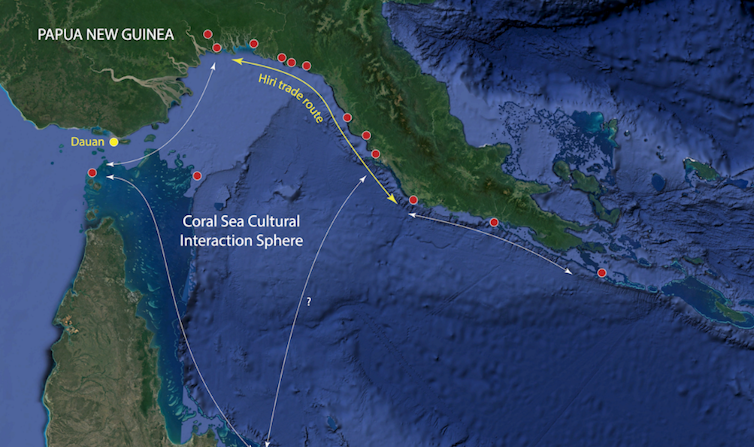

It has long been assumed that Indigenous Australia was isolated until Europeans arrived in 1788, except for trade with parts of present day Indonesia beginning at least 300 years ago. But our recent archaeological research hints of at least an extra 2,100 years of connections across the Coral Sea with Papua New Guinea.

Over the past decade, we have conducted research in the Gulf of Papua with local Indigenous communities.

During the excavations, the most common archaeological evidence found in the old village sites was fragments of pottery, which preserve well in tropical environments compared to artefacts made of wood or bone. As peoples of the Gulf of Papua have no known history of pottery making, and the materials are foreign, the discovered pottery sherds are evidence of trade.

This pottery began arriving in the Gulf of Papua some 2,700 years ago, according to carbon dating of charcoal found next to the sherds.

By Chris Urwin, Alois Kuaso, Bruno David, Henry Auri Arifeae, Robert Skelly

This means societies with complex seafaring technologies and widespread social connections operated at Australia’s doorstep over 2,500 years prior to colonisation. Entrepreneurial traders were traversing the entire south coast of PNG in sailing ships.

There is also archaeological evidence that suggests early connections between PNG and Australia’s Torres Strait Islands. Fine earthenware pottery dating to 2,600 years ago, similar in form to pottery arriving in the Gulf of Papua around that time, has been found on the island of Pulu. Rock art on the island of Dauan further to the north depicts a ship with a crab claw-shaped sail, closely resembling the ships used by Indigenous traders from PNG.

It is hard to imagine that Australia, the Torres Strait and PNG’s south coast were not connected.

An unconventional trade

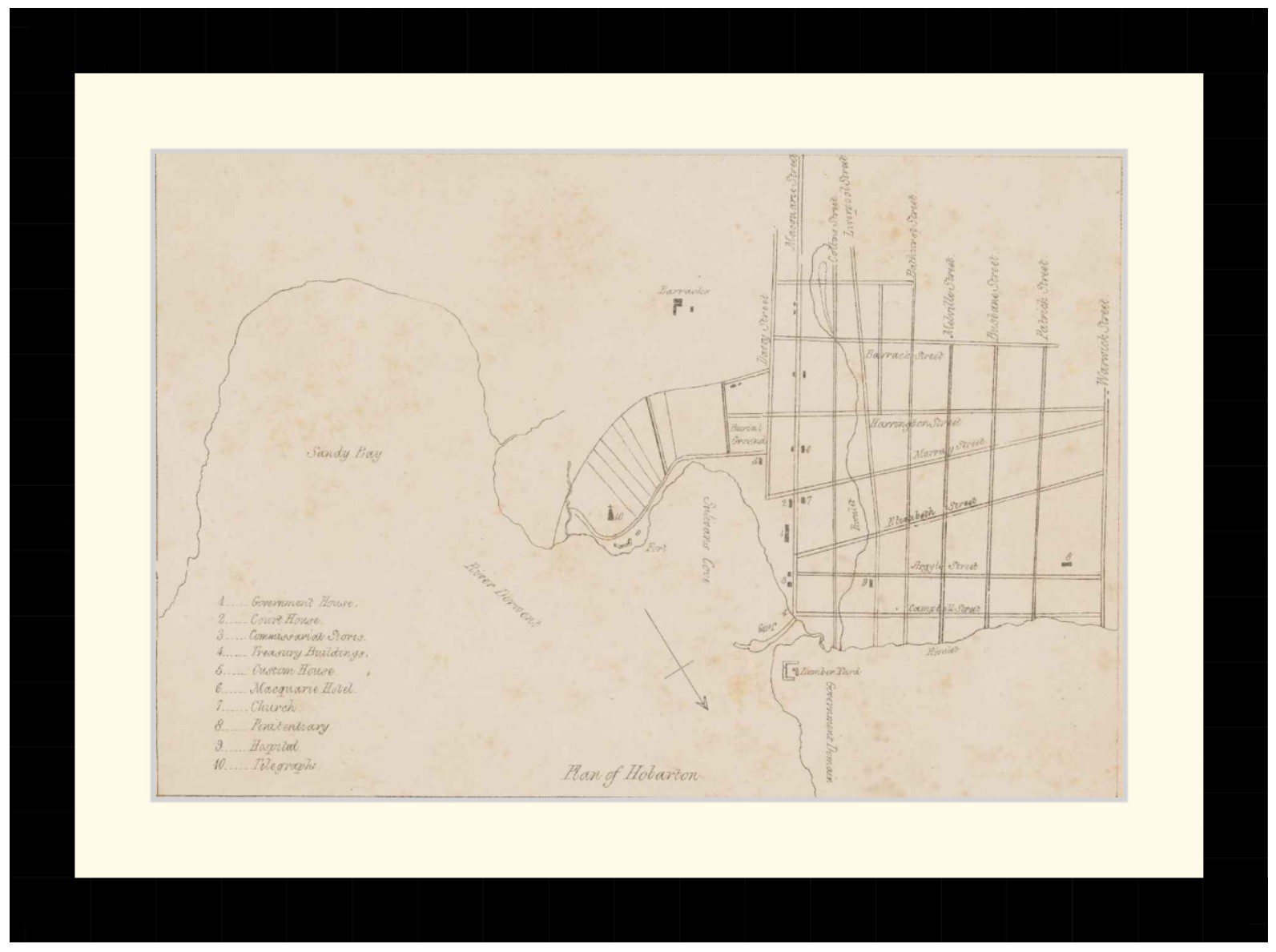

The trade itself was quite remarkable. When British colonists arrived in Port Moresby (now the capital of PNG) in 1873, some 130 kilometres from the start of the Gulf of Papua to the west, they wrote in astonishment of the industrial scale of pottery production for maritime trade by Indigenous Motu communities.

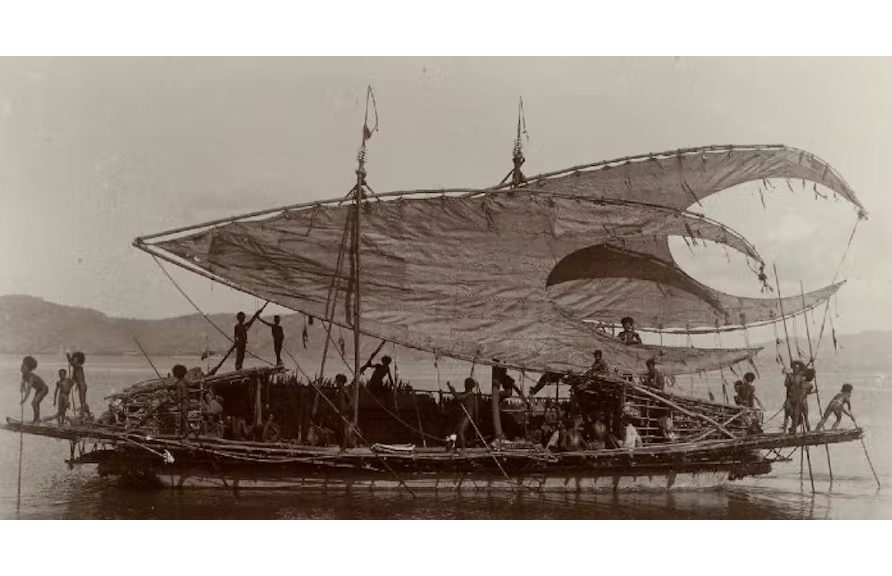

Each year, Motu women would spend months making thousands of earthenware pots. Meanwhile the men built large trading ships, called lakatoi, by lashing together several dugout hulls. The ships measured 15-20 metres long and had woven sails in the shape of crab claws.

In October and November, Motu men would load the pots into the ships and sail west towards the rainforest swamplands of the Gulf of Papua. The trade on which they embarked was known as hiri. The voyages were perilous, and lives were sometimes lost in the waves.

When the men arrived – having sailed up to 400 kilometres along the coast – the Motu were in foreign lands. People living in the Gulf of Papua spoke different languages and had different cultural practices. But they were not treated like foreigners.

Sir Albert Maori Kiki, who became the Deputy Prime Minister of PNG, grew up in the Gulf of Papua in the 1930s. He described the arrival of the Motu in his memoirs:

The trade was not conducted like common barter […] the declarations of friendship that went with it were as important as the exchange of goods itself […] Motu people did not carry their pots to the market, but each went straight to the house of his trade relation, with whom his family had been trading for years and perhaps generations.

In exchange for their pots, the Motu were given rainforest hardwood logs from which to make new canoes, and tonnes of sago starch (a staple plant food for many people in Southeast Asia and across the island of New Guinea).

The Motu would stay in Gulf villages for months, waiting for the wind to change to carry them back home.

Quantity overtakes quality

Pottery has been traded into the Gulf of Papua for 2,700 years, but the trade grew larger in scale about 500 years ago. Archaeological sites of the past 500 years have much larger quantities of pottery than those before them. The pottery itself is highly standardised and either plain or sparsely decorated, in contrast with older sherds that often feature ornate designs.

In the past 500 years it seems that pottery makers valued quantity over quality: as greater quantities of pottery were traded into the Gulf of Papua, labour-intensive decorations gradually disappeared.

We think this is when the hiri trade between the Motu and rainforest villages of the Gulf of Papua began in earnest.

The coming decades promise further findings that will help unravel the forgotten shared history of PNG and Indigenous Australia across the Torres Strait. But it is becoming increasingly clear that Indigenous Australia was not isolated from the rest of the world.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Articles you may also be interested in

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.