ABUSE AND TENACITY: UKRAINE’S STRUGGLE FOR AUTONOMY

Reading time: 10 minutes

The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine has rightfully outraged and shocked much of the world; a war of aggression from one nation to another, this attack and occupation has been the largest such incursion into a foreign land in Europe since the Second World War. It has also caused the displacement of nearly 4 million Ukrainians, leading to Europe’s greatest refugee crisis in 80 years.

By Michael Vecchio

Throughout this continuing war many in the Western world, unattuned to the policies of Russian president Vladimir Putin, have been caught with surprise at this seemingly sudden attack on a sovereign Ukraine. Yet throughout his presidency (a post he has occupied largely uninterrupted for 22 years), Putin has shown no reservations that a reclamation of past Russian glory would be key to preserve the modern state. In fact he has made it abundantly clear that the collapse of the Soviet Union was perhaps the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century”.

With Ukraine’s formal independence in 1991 following the USSR’s collapse, an inevitable feeling of optimism and jubilation filled the minds and hearts of many Ukrainians; the opportunity to forge a long delayed Ukrainian state free from outside domination was here, but could it be attained?

READ MORE: FOUR DAYS IN AUGUST: THE SOVIET UNION’S FINAL BLOW

According to Vladimir Putin, not only should it not be attained, but efforts to do so directly “threaten” Russia’s “right” to territorial hegemony in the region; since 1991 Ukraine has travelled an uneasy road to assert its unique ethnic and political voice, and though it has achieved a modicum of sovereignty, still the shadow of Mother Russia remained ominous

.

Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, the Ukrainian government struggled with widespread corruption, efforts for democratization, and in establishing a firm free market economy. To make matters worse for the ever-suppressed nationalist sentiment, although the country was considered sovereign, those who occupied the seats of power in Kyiv, were often still under the influence of Moscow.

High ranking officials, including the Ukrainian President, were often accused of corruption and collusion with the Russian state (who itself struggled economically and socially in the post-Soviet period); this was perhaps none more evident than with President Leonid Kuchma, whose eleven years in power saw numerous election irregularities, widespread patronage appointments, and close alignment with Russian policies.

READ MORE: A BRIEF HISTORY OF CORRUPTION IN UKRAINE, THE KUCHMA ERA

It was a toxic legacy that spread throughout Ukrainian society, and that culminated in the 2004 Orange Revolution. When the results of the presidential election to replace Kuchma were revealed it was obvious that tampering and fraud had taken place.

Reports from election monitors claimed rampant interference and voter intimidation from candidate Viktor Yanukovych’s camp, which ultimately saw him take the lead in the first round of voting. That Yanukovych, a known ally of Vladimir Putin and supporter of Russian integration, was associated with such an accusation surprised very few.

Thus thousands congregated on Kyiv’s Independence Square demanding not only a re-vote, but to openly reject the atmosphere of corruption and foreign (particularly Russian) meddling. Adopting the colour orange from the campaign of opposition candidate Viktor Yushchenko, the Orange Revolution was a peaceful, yet forceful show of Ukrainian nationalism. Over a period of two months from November 2004 to January 2005, protestors demanded a re-vote and stricter enforcement of election laws. The Ukrainian Supreme Court declared a second ballot be held in December.

In the re-vote, Viktor Yushchenko, who openly promoted closer ties to Western Europe away from Russia, resoundingly defeated Yanukovych by a margin of 3 million votes. During the course of the original campaign, Yushchenko had been poisoned by a dioxin chemical compound, and was disfigured as a result.

This failed attempt on his life, the protests, and his subsequent electoral victory was seen by many as an allegory for Ukraine as a whole. “Poisoned” for so long, Ukraine like Yushchenko emerged victorious from attempts on its livelihood and hoped that the period following the Orange Revolution would be a new beginning for the Cossack nation.

But Yushchenko’s presidency ultimately failed to live up to its expectations and though inherently less corrupt than its predecessors, did not bring Ukraine to a state of economic or social prosperity. The country remained amongst the poorest in Europe with a relatively low life expectancy, while efforts to curb patronage and corruption were only moderate at best. Indeed those involved in Yanukovych’s illegal means were never brought to justice, and many oligarchs who accounted for much of the financial disparity in the nation mostly continued their lavish lifestyle.

It was with this disappointing term as president that when election time came around again in 2010, Viktor Yushchenko’s own party refused to nominate him again. Thus came the time once more for Viktor Yanukovych who presented himself as a reformed candidate, promising to maintain closer ties with the European Union and not Russia.

In the 2010 election, Yanukovych won a plurality of votes (not a majority) and finally became Ukraine’s President, in a vote that observers said was fair. In spite of pledges to navigate Ukraine on its own independent path, it was Viktor Yanukovych’s broken promises that led to an unprecedented crisis in the modern Ukrainian state: the 2014 Euromaidan Uprisings.

To understand the immediate causes of Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, one must look back only to 2014 and the astounding events of the Euromaidan. From the word “Maidan” meaning public square, the Euromaidan protests in Kyiv’s Independence Square (and in other locations), quickly eclipsed the rather peaceful demonstrations of the Orange Revolution.

President Yanukovych reneged on his government’s promise to have the country join the European Union-Ukraine Association Agreement, in favour once more of a closer economic integration with the Kremlin. It was the proverbial “straw that broke the camel’s back” for millions of Ukrainians.

READ MORE: Understanding Ukraine’s Euromaidan Protests

And thus what began as protestation against the breaking of this promise evolved into protests against the status quo in Ukraine. A status quo that treated corruption as a regular occurrence, a status quo that cozied up to big brother Russia and a status quo that severely limited Ukrainians from having a say into the way they wished to see the future of their country proceed.

Although it began simply as demonstrations in Kyiv’s Independence Square the spirit of the Euromaidan captivated much of Ukraine. This was most particular in the western portion which was more inclined to ally itself with Europe and away from Moscow’s influence. Most unfortunately these mass demonstrations ended up becoming violent; in part because Yanukovych responded with police and military force and because factions of the protestors called for the use of violence to achieve their goals, resulting in numerous injuries and hundreds of fatalities.

As the violence escalated and calls for his resignation grew louder, Viktor Yanukovych fled the country on the night of February 22, 2014, exiling himself into the welcome hands of Russia; responding to the “fascist” threat and its strategic interests in a Ukraine that had clearly shown its fatigue with Russian dominance, Russia declared that it would act on behalf of Russians in Ukraine that needed ‘protection’ from a hostile new government in Kyiv.

Annexing the Crimean Peninsula, due to its large presence of Russian speakers and its historical ownership by Russia, Putin did not shy away from openly espousing the belief that “Russians and Ukrainians are essentially one people”. The residents of Crimea he claimed did not approve of the events on the Maidan and wanted to be a part of Russia once again.

In the Donbass region in Eastern Ukraine, the oblasts of Luhansk and Donetsk under the control of pro Russian rebels declared their unilateral ‘independence’ from Ukraine. They later proclaimed their status as Autonomous republics with a desire to be closer to Russia. In this now protracted war in the Donbass between the Ukrainian government and these separatists, at least 9,000 have perished, while Crimea has been totally taken over.

And so we find ourselves in 2022; while the seeds for Russia’s major invasion can be traced directly to the events of 2014, this conflict is really rooted in centuries of history. Although Vladimir Putin has declared the Ukrainian state a “construct of Russia” this troubling take is hardly a view shared by Putin alone. In fact this idea of a “united” Russia and Ukraine has a long history that grew out of centuries of dominance over Ukraine by the Russians.

Russian propaganda has long pointed to such historical entities like Kyivan Rus’, as a means to justify assaults on Ukrainian sovereignty. The first political manifestation of common Slavic peoples, Kyivan Rus’ (founded circa 862 AD) was a loose confederation of various emerging states that included Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia. Indeed modern Russia and Ukraine can trace their historical lineage to Kyivan Rus’, and the similarities in their respective languages and cultures is evident.

READ MORE: HISTORY OF KYIVAN RUS

After Kyivan Rus’ fell to the Mongols the area we now know as Ukraine became passed around to other principalities, never having its own independent voice.

Even before Ukraine’s traumatic history as a part of the Soviet Union, the Ukrainian nation had long been subdued and gagged, prohibited from achieving any aspirations of independent statehood. Contested, ruled, and divided by various external political entities that included the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Ottoman Empire, and of course the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, Ukraine’s identity and autonomy has been stifled seemingly since time immemorial.

But how does Ukraine fit into the narrative of Russian glory? Putin and those supporting Russia’s claims continue to irresponsibly cite that because Ukraine was a part of Russia historically, then it should continue to be a part of it today. This argument completely reneges on agreements made with Ukraine to recognize its sovereignty but furthermore it continues to trample on the nation’s efforts to define itself and have the right to control its future.

Since the Euromaidan, the Ukrainian government, and its Presidents, Petro Poroshenko and Volodymyr Zelenskyy, respectively, continued to promote Ukraine’s desires for integration with the West; though parts of its territory remained under Russian occupation, this did not deter Kyiv from seeking membership in NATO and the European Union.

It was precisely these desires that finally led to Vladimir Putin’s decision for a full-scale invasion; the perceived threat of a Western oriented Ukraine contradicts directly with Putin’s goals of creating a new colonial order. “Restoring” Ukraine’s place as part of a larger Russian authority and preventing the further expansion of democratization, is thus a warped justification for this dangerous war.

Putin and company may use Kyivan Rus, Soviet history, and the events of the Euromaidan to justify their means and flagrant displays, but ultimately it is a hideous assault on a nation that has bided their time for far too long. It has not willingly been a part of Russia’s “soul” but forced in a corner and told how to behave.

For the people of Ukraine have long suffered injustice and punishment for committing one ‘crime’: being Ukrainian. Yet as their national anthem declares:

“Ukraine is not yet dead, nor its glory and freedom,

Fate will still smile on us brother-Ukrainians.

Our enemies will die, as the dew does in the sunshine,

and we, too, brothers, we’ll live happily in our land.”

Podcast episodes about this topic

Other Articles you may like

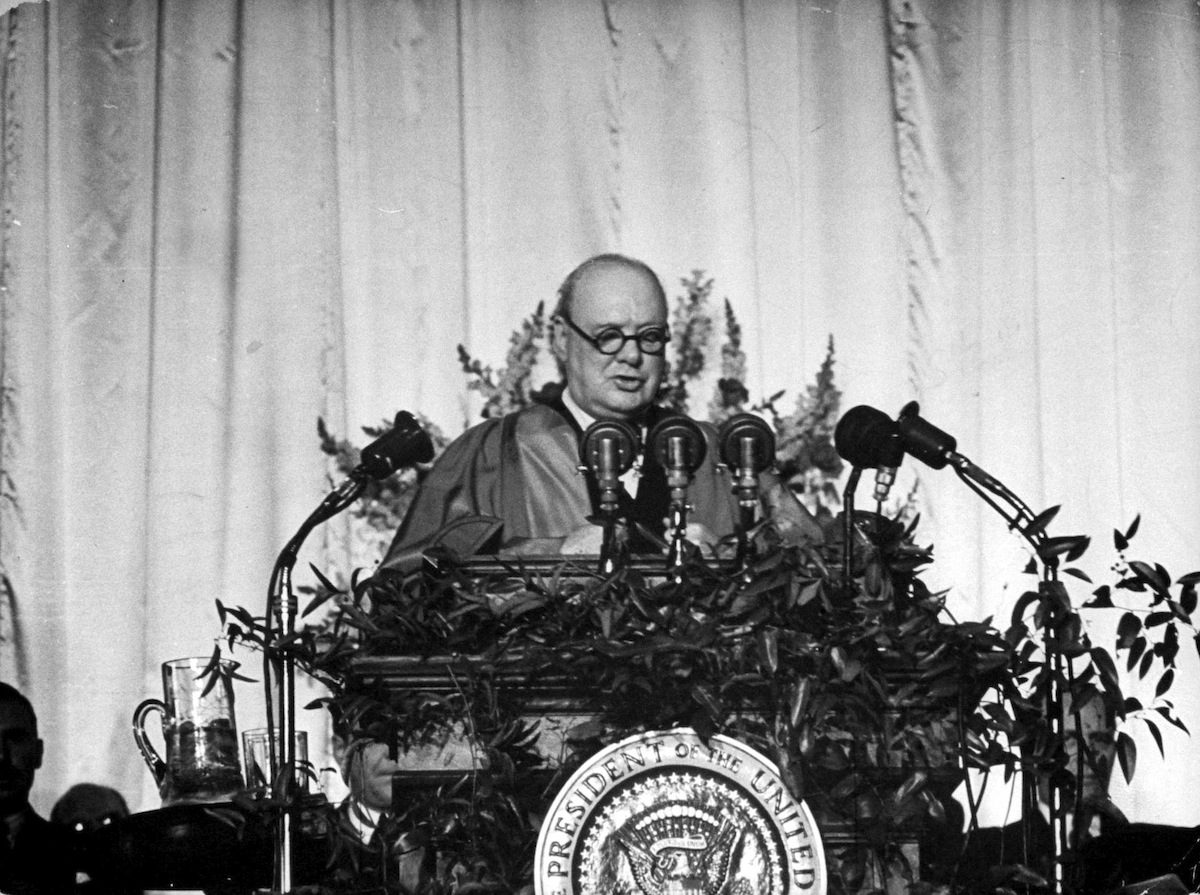

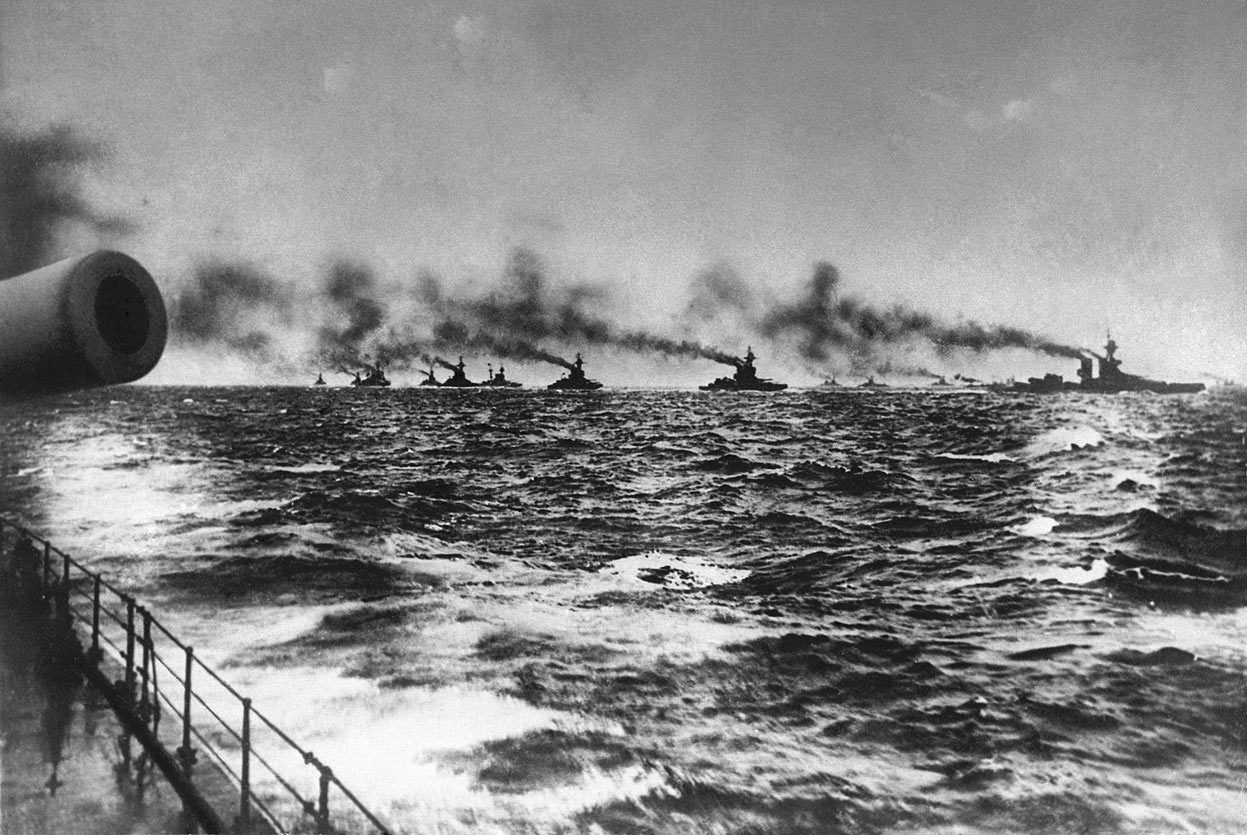

Losing the war in an afternoon: Jutland 1916

1916 was the pivotal year in the First World War. In February German forces attacked the French at Verdun, while 1 July will mark the anniversary of the Anglo-French offensive on the Somme.

History’s Greatest Nicknames

Reading time: 7 minutes

A browse through any military history book will no doubt bring up titles of famous officers, often bearing unusual, surprising, or sometimes downright hilarious nicknames. In many cases, it’s clear where the sobriquet originated, while other examples hold a less-obvious significance.

THE FORGOTTEN WAR CRIMES OF FASCIST ITALY

Reading time: 14 minutes

In just five short years, the combined forces of the Axis powers managed to commit atrocities and war crimes on a scale never equalled before or after. But while Axis war crimes came into sudden shocking clarity with the Allied victory in 1945, one Axis power is still overlooked to this day: Italy.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.