Reading time: 14 minutes

In just five short years, the combined forces of the Axis powers managed to commit atrocities and war crimes on a scale never equalled before or after. But while Axis war crimes came into sudden shocking clarity with the Allied victory in 1945, one Axis power is still overlooked to this day: Italy.

By Morgan Dunn

The seedbed of fascism, the downfall of the League of Nations, and an adventuring imperial power in the 1930s, Benito Mussolini’s regime was responsible for its share of atrocities, too.

THE PRELUDE: ETHIOPIA

A defining feature of Mussolini’s Italy was its ambition to expand through conquest with no regard for the laws of war or human rights. The underlying fascist principle was spazio vitale, or “living space” – a direct analogue of the Nazis’ Lebensraum.

In 1935, the 12-year old Fascist regime had already completed the “Pacification” of Libya, subjecting thousands of Libyans to torture and massacres and depriving them of land and livestock. During the Libyan campaign, General (later Marshal) Rodolfo Graziani had been brutally efficient enough to earn the nickname “the Butcher of Fezzan.”

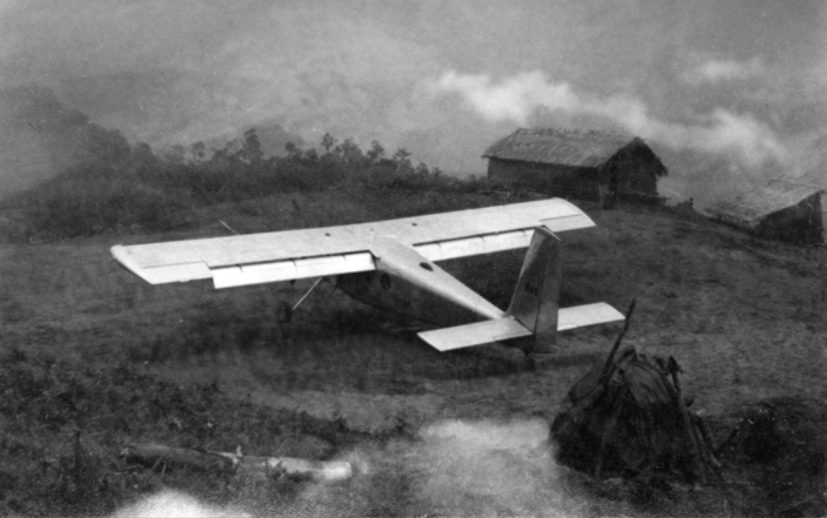

So when Mussolini set his sights on the ancient Ethiopian Empire, his forces were no strangers to wartime atrocities. Beginning in October 1935, over half a million Italians decimated untrained and ill-equipped Ethiopians using modern tanks, automatic weapons, aircraft – and gas.

Despite being bound by the 1925 Geneva Protocol banning the use of chemical weapons, Italian forces deployed up to 500 tons of mustard gas in Ethiopia, often with Mussolini’s direct permission. In one message, the Duce authorized Marshal Pietro Badoglio to “use even on a vast scale of any gas and flamethrowers.” Badoglio was only too happy to comply, dropping 40 tons of mustard gas on retreating Ethiopians at the Battle of Amba Aradam alone.

The Italian onslaught, begun without a declaration of war, proved too much for Ethiopia. During his dramatic address to the League of Nations in May 1936, Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie described how “in tens of thousands the victims of Italian mustard gas fell.” But for Ethiopia, war was just the beginning.

THE BUTCHERS

In July, after Mussolini declared “Ethiopia is Italian,” occupation forces imprisoned “hundreds of higher-level Ethiopian nobility and functionaries,” while sending “other “ordinary” patriots, intellectuals, educated persons, and their families to concentration camps.” Italian occupying forces would continue to visit extreme violence on civilians and resistance fighters alike, once massacring 2,500 Arbegnoch rebels in Ametsegna Washa – “the cave of the rebels.”

As Graziani put it, “The Duce will have Ethiopia, with or without the Ethiopians.” After two Eritreans attempted to assassinate the general, Graziani embarked upon a grisly campaign of reprisals in February 1937, killing as many as 30,000 civilians. Yekatit 12, as the Ethiopians called it, earned Graziani a second nickname: “the Butcher of Ethiopia.”

Another Italian of note in Ethiopia was Pietro Maletti. Like Graziani, Maletti had played a part in the Libyan horrors, and would expand his record when he ordered the slaughter of 2,000 monks and pilgrims at the monastery of Debre Libanos, which his men then looted. Ethiopia would have to wait until 1941 to be freed of the Italian scourge.

WORLD WAR II: VIOLENCE WRIT LARGE

Fascist Italy reached its imperial zenith in the 1930s, when Mussolini launched the country on a series of military adventures in the Spanish Civil War, Albania, and the invasion of France, all accompanied by a range of abuses. From 1939 onward, poor economic planning and an effort to keep up with the growing conquests of their German allies set the Italian military back.

But as Mussolini said in 1941, “although anything may happen Italy will march with Germany, side by side, to the end.” Italy couldn’t match Germany for sheer destruction and human misery on an industrial scale – but that didn’t stop them trying, in Greece, Yugoslavia, and beyond.

ITALIAN BRUTALITY IN GREECE

Italy’s war crimes in Greece are not well-known, particularly in the English-speaking world. 21st century research has hinted at a program of rape, destruction of homes and property, economic exploitation, torture, and widespread civilian massacres.

The best-known of these is the Domenikon Massacre of February 1943, in which 175 Greek men were murdered by Italian troops.

According to one historian, the massacre was one of many in which thousands of Greek civilians were killed as reprisals for Greek resistance activity. Also of note was the Great Famine of 1941-42, which killed as many as 300,000 Greeks as Italian, German, and Bulgarian forces plundered the country.

IMPERIAL ITALY: YUGOSLAVIA

One country where Italian war crimes are well-documented was Yugoslavia. The Royal Yugoslav Army had wilted in the face of a week-long Axis assault in April 1941, begun without a declaration of war as in Ethiopia. Germany, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Italy dismembered the country.

But, like in Greece, defeat was merely the catalyst for a resistance movement which would eventually not only crush the occupation, but establish a revolutionary postwar order.

The star of Italy’s campaign of repression was General Mario Roatta, who took command of the Italian Second Army in January 1942. He immediately adopted a policy of “not a tooth for a tooth, but a head for a tooth.”

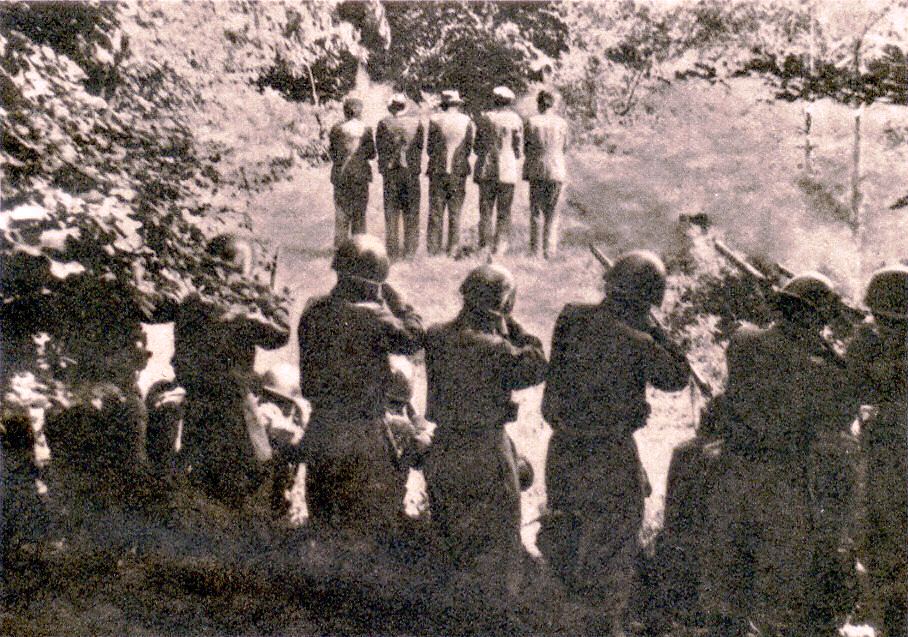

In February, Roatta’s men began shooting prisoners and burning homes suspected of harboring Partisans. The following month, he put his new strategy to paper in an order titled Circular 3C.

3C enabled officers to imprison any man between the ages of 16 and 60 in combat zones; to hold Partisans’ family members, sympathisers, and local elites as hostages; and to execute civilians in reprisal for Partisan attacks. 3C also disposed of consequences for Italian troops:

“Let it be understood that excessive reactions, undertaken in good faith, will never be prosecuted!”

Moreover, the new order instructed Italian soldiers to shoot captured Partisans on the spot. Wounded and female Partisans and those under 18 years old were to be spared – but Roatta ordered that this be left out of the printed version.

3C received personal approval from Mussolini, who told Roatta that “the best situation is when the enemy is dead. So we must take numerous hostages and shoot them whenever necessary.”

Italian military and police forces, often in cooperation with their allies, the royalist Serbian Chetniks, murdered some 4,400 Yugoslavs by 1943. Chetnik units slaughtered nearly 70,000 more, often under Italian protection. The full extent of the violence and damage, masked by the ongoing resistance war, may never be known.

THE ITALIAN CONCENTRATION CAMP SYSTEM

From its inception in 1922, the Fascist regime in Italy had used prison as a tool to silence and punish. In addition to normal prisons, the Italians established concentration camps in Libya, Eritrea, Somalia, Montenegro, Croatia, and Italy itself. After the passage of the Italian Racial Laws in 1938, victims of the concentration camp system included increasing numbers of Italian Jews.

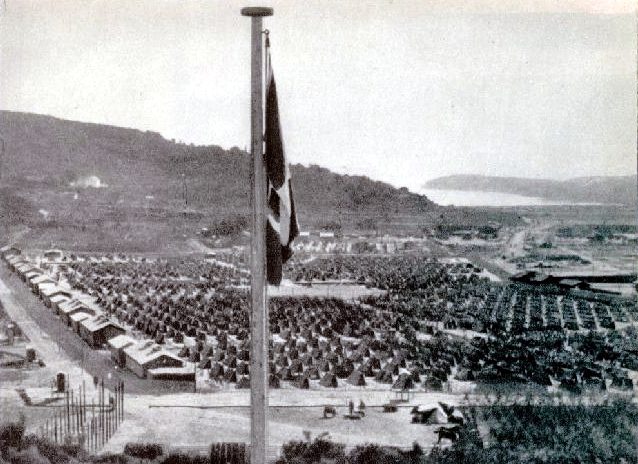

These camps were smaller and less numerous than the German ones, but no less brutal. Between 1941 and 1943, over 100,000 civilian Serbs, Croats, Montenegrins, and Slovenes were subjected to exposure, starvation, physical violence, and forced labor in Italian prison camps.

The deadliest and most notorious of them was on Rab, a Croatian island annexed by Italy in 1942. There, 10,000 captives were crammed into open-air prisons which were “filthy, muddy, overcrowded and swarming with insects.”

Prisoners, including “pregnant women and children, were quartered six to a tent and slowly starved.” Dysentery and lice were facts of life on Rab. “Italian sailors ferrying inmates back to the mainland were shocked by their emaciated state and gently helped them ashore.”

Photographs taken after the liberation of the island were so shocking they were often mistaken for images of the Nazi camps in Eastern Europe in the postwar era. The same horrific images could be seen at camps across the Italian realm.

Only in September 1943, when Mussolini’s regime crumbled, were the inmates freed. Even then, many infirm or older inmates were left behind to fall into the hands of the Nazis.

AFTER THE FALL

By the summer of 1943, Allied planes were bombing Rome, and the Allied invasion of Sicily was well underway. War-strained Germany could no longer afford to prop up its southern ally.

On July 24th, King Victor Emmanuel III fired Mussolini, replacing him with Marshal Badoglio. The deposed dictator was imprisoned until a Waffen-SS commando unit extracted him from a hotel in the Apennine Mountains on 12th September.

Until then, Italy’s Jews had suffered the loss of their civil rights and property and discrimination in employment and education – but not deportation or mass murder.

In the new Italian Social Republic (Repubblica Sociale Italiana), set up in the German-occupied north with Mussolini installed as a figurehead ruler on 23th September 1943, Jewish Italians could expect no such mercy.

Following the reclassification of Italian Jews as foreigners, RSI Police Order No. 5, issued on 30th November 1943, authorized RSI police to arrest Jews to be handed over to the Germans. Almost 8,000 would lose their lives, either in Italy or in Auschwitz.

For the rest of the war, the forces of the RSI had their hands full struggling to preserve the puppet state while battling Italian Partisans. Aside from collusion in a number of German war crimes and several small-scale massacres of partisans, Fascist Italy’s capacity for terror was finished.

After Mussolini’s impromptu execution, Rodolfo Graziani surrendered what remained of the RSI, and Mussolini’s imperial dreams, on 29 April, 1945.

NUREMBERG, TOKYO … ROME?

With the signing of the Armistice of Cassibile, Italy was converted into an ally under the leadership of Marshal Badoglio, with the Italian Co-Belligerent Army, Navy, and Air Force fighting the faltering Germans and RSI for the remainder of the Second World War.

The Soviet Union, United States, and the United Kingdom required Italy to bring war criminals to trial. Three years later, the Treaty of Paris between Italy and the Allied Powers reaffirmed this obligation, which also covered war crimes committed in Ethiopia.

Major trials at Nuremberg and Tokyo were carried out to deliver some form of justice. In Italy, arrest warrants and suspect lists were made and a commission of inquiry was set up. Then nothing happened.

From 1944, the Italian government’s unofficial policy was to avoid or delay war crimes trials. The reasoning was complex: Italians had suffered at the hands of German war criminals from 1943, and thus had the right to bring cases before the United Nations.

But postwar Italy’s leaders realised that doing so would risk setting a precedent allowing Ethiopia, Yugoslavia, Greece, Albania, and Libya to press charges of their own. The fragile new Italian Republic, established in June 1946, and the reconstituted Italian military, they believed, couldn’t withstand the scandal.

So in contrast to other former Axis powers, a long, dark legacy of brutality was simply ignored. Even in cases where war criminals were pursued, leaders protected the accused. “Try to gain time, avoid answering requests,” read a 1948 message from Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi to an Italian civil servant involved in such a case.

The former Allies played a part, too. Britain and the United States in particular were not eager to give the powerful Italian Communist Party political ammunition. Besides, if Ethiopia could prosecute Italians for war crimes, how could Britain and France protect colonial military and political leaders from similar charges as their empires dissolved in the postwar years?

De Gasperi wrote that Italy must try “to save whatever can be saved.” Instead of atonement, there arose a myth: Italiani, brava gente, or, “Italians, the good folks.” Italians chose to believe they were fundamentally innocent, and had been hoodwinked by Mussolini.

Only a handful of diehard Italian Fascist leaders were executed in the immediate aftermath of the war. But for most, including Mario Roatta and Pietro Badoglio, the postwar years meant comfortable retirement, dying in old age, and an escape from justice.

Podcast about Italian War Crimes

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 79

History Guild General History Quiz 79See how your history knowledge stacks up! Want to know more about any of the questions? Once you’ve finished the quiz click here to learn more. Have an idea for a question? Suggest it here and we’ll include it in a future quiz! The stories behind the questions 1. Approximately […]

The Antarctic Treaty is turning 60 years old. In a changed world, is it still fit for purpose?

The 1959 Antarctic Treaty celebrates its 60th anniversary this week. Negotiated during the middle of the Cold War by 12 countries with Antarctic interests, it remains the only example of a single treaty that governs a whole continent. It is also the foundation of a rules-based international order for a continent without a permanent population. The treaty […]

General History Quiz 188

1. What was the name of the airline the CIA established to covertly move agents?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.