Reading time: 3 minutes

The working day as we now know it was the result of international, cross-industry labour efforts from workers, unions and activists, spanning well over a century of campaign, unrest and even death. The Industrial Revolution, with the spread of electrical lighting and extremely low hourly wages, had ended the traditional, rural working patterns of sun up to sun down, and meant that in some industries workers were forced to endure up to 18-hour shifts.

By Anna McEvinney

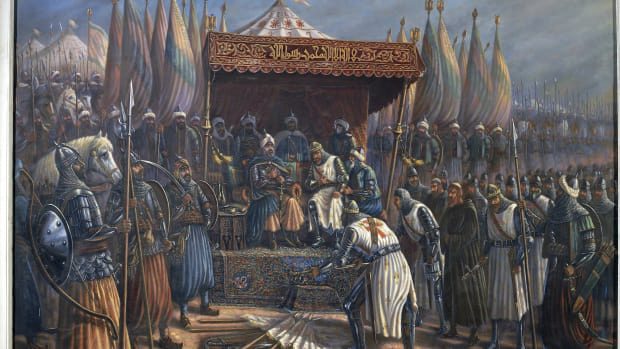

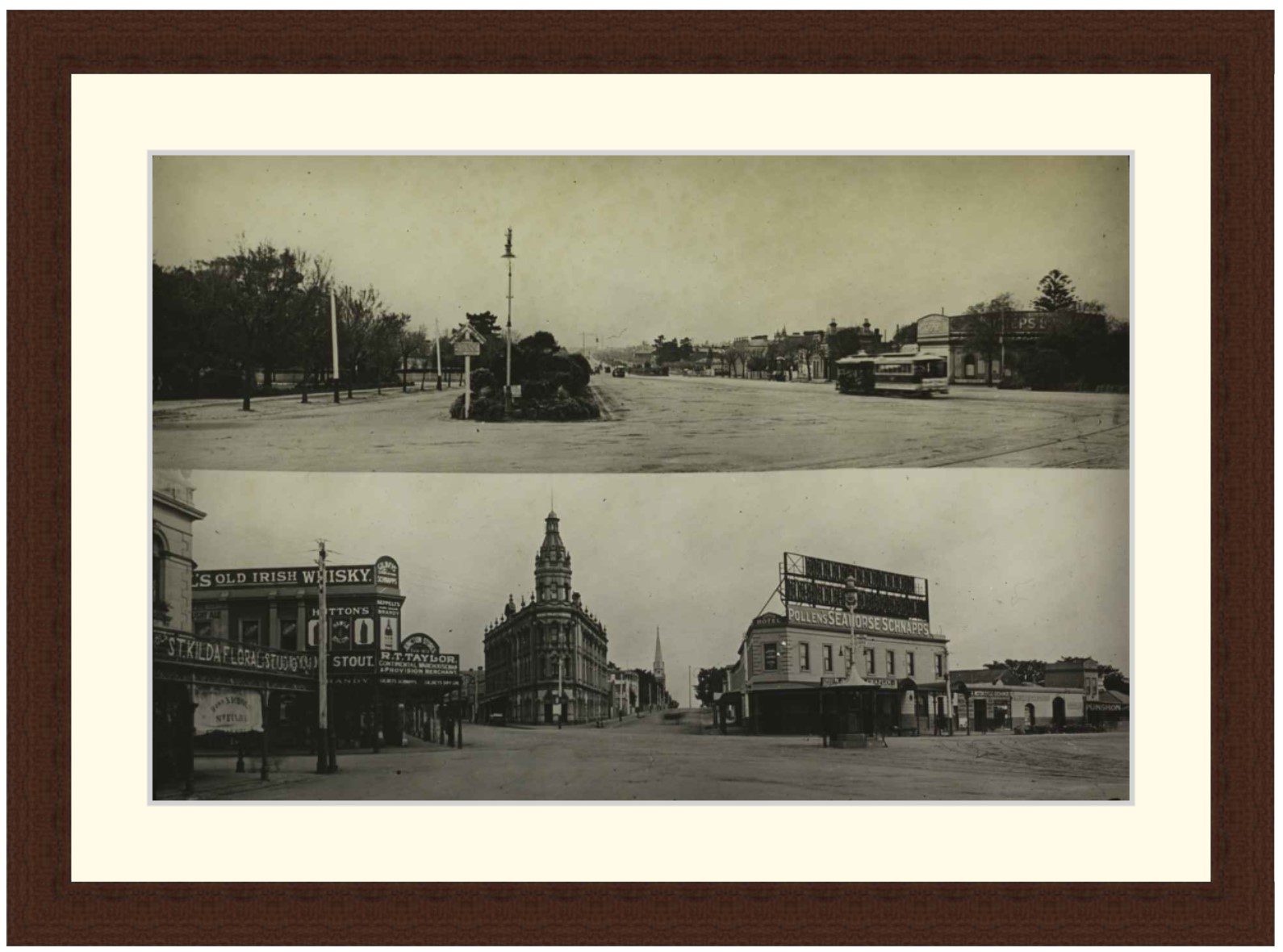

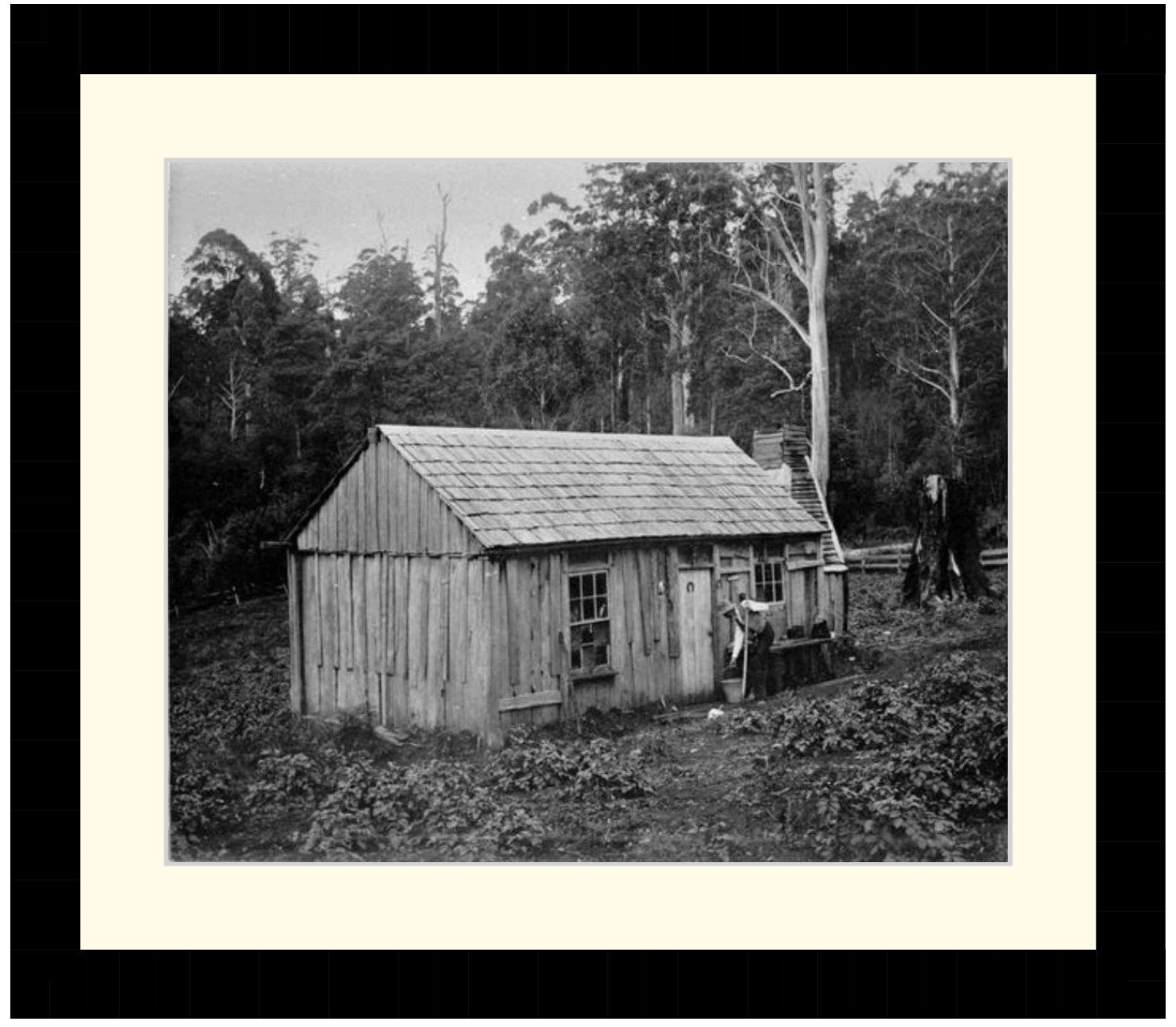

The cause was spearheaded primarily by workers in Australia, Britain and the USA. Each nation had its own nuanced conditions and reasoning for campaign: In Australia, for example, the end of transportation in the 1840s and the movement of many labourers to the goldfields led to a shortage of workers and thus increased bargaining power. Moreover, the Melbourne Stonemason’s Union cited the unbearably hot summer weather as a basis for reducing the working day from ten hours. In 1856, led by the union, workers downed tools and over several months negotiated for themselves an eight-hour day, maintaining their ten-hour wages. This was the cornerstone on which the fight for a universal eight-hour day was built.

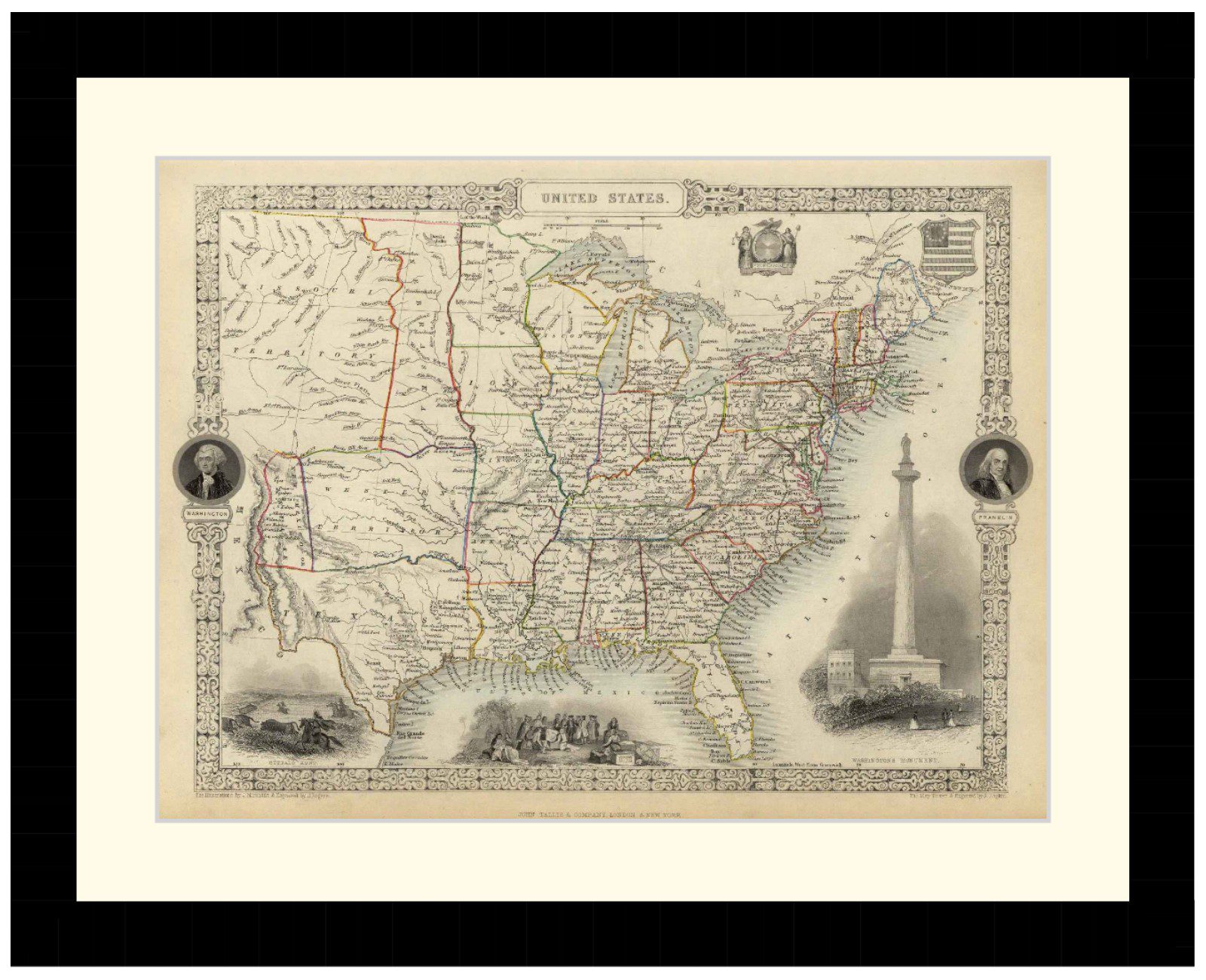

In the US, campaigning for an eight-hour day had tentatively begun in 1791, when Philadelphia workers had organised to campaign for a ten-hour day, including two hours for meals. Over decades, intermittent strikes and protests continued along with the formation of several ‘Eight Hour Leagues’, until things came to a head at the inaugural May Day Parade of 1886. 350,000 workers walked out of their positions to protest for shorter working hours, and over the next few days matters became heated. Things came to a head when police opened fire on a protesting crowd, killing four.

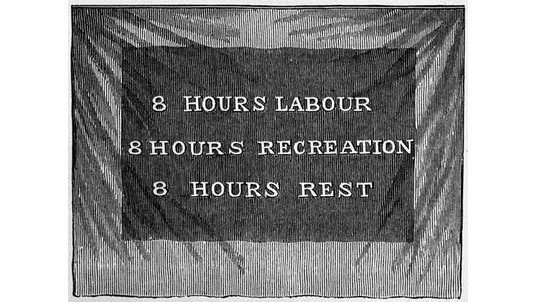

In 1817, the British proto-socialist Robert Owen, of New Lanark, coined his slogan: ‘Eight Hours’ Work, Eight Hours’ Rest, Eight Hours’ Recreation’. Unpopular amongst business owners, the campaign did not gain widespread traction until in 1884 Robert Mann founded the Eight Hour League, which convinced the Trades Union Congress to establish the eight-hour day as one of their foremost goals — a crucial step.

Decades of activism were the primary driving force for the eight-hour day, but there were other factors in play. Henry Ford, the famous motoring manufacturer, is often considered one of the catalysts behind the decrease in working hours. In 1914, he doubled employee wages and cut their hours from 48 to 40 per week. Ford realised that he could make more money, and retain greater employee loyalty, by reducing working hours. In 1926, he argued: ‘It is high time to rid ourselves of the notion that leisure for workmen is either “lost time” or a class privilege’. Seeing the success of his venture, some other employers tentatively followed, and the forty-hour working week gradually became more widespread, until finally the Fair Labour Standards Act was introduced in 1938, assuring a forty-hour working week for all.

There was even more nuance to the decrease in working hours: the foundations of the eight-hour working day were laid during the Victorian period, famous for its preoccupation with virtue. There was general concern about the moral lives and education of workers, and it was argued that an eight-hour day would allow ample leisure time for employees to morally educate themselves, and to act in their free time as upstanding citizens and attentive fathers and husbands.

The video below describes how this came about.

Podcast Episodes about the 8 Hour Working Day

Articles you may also like

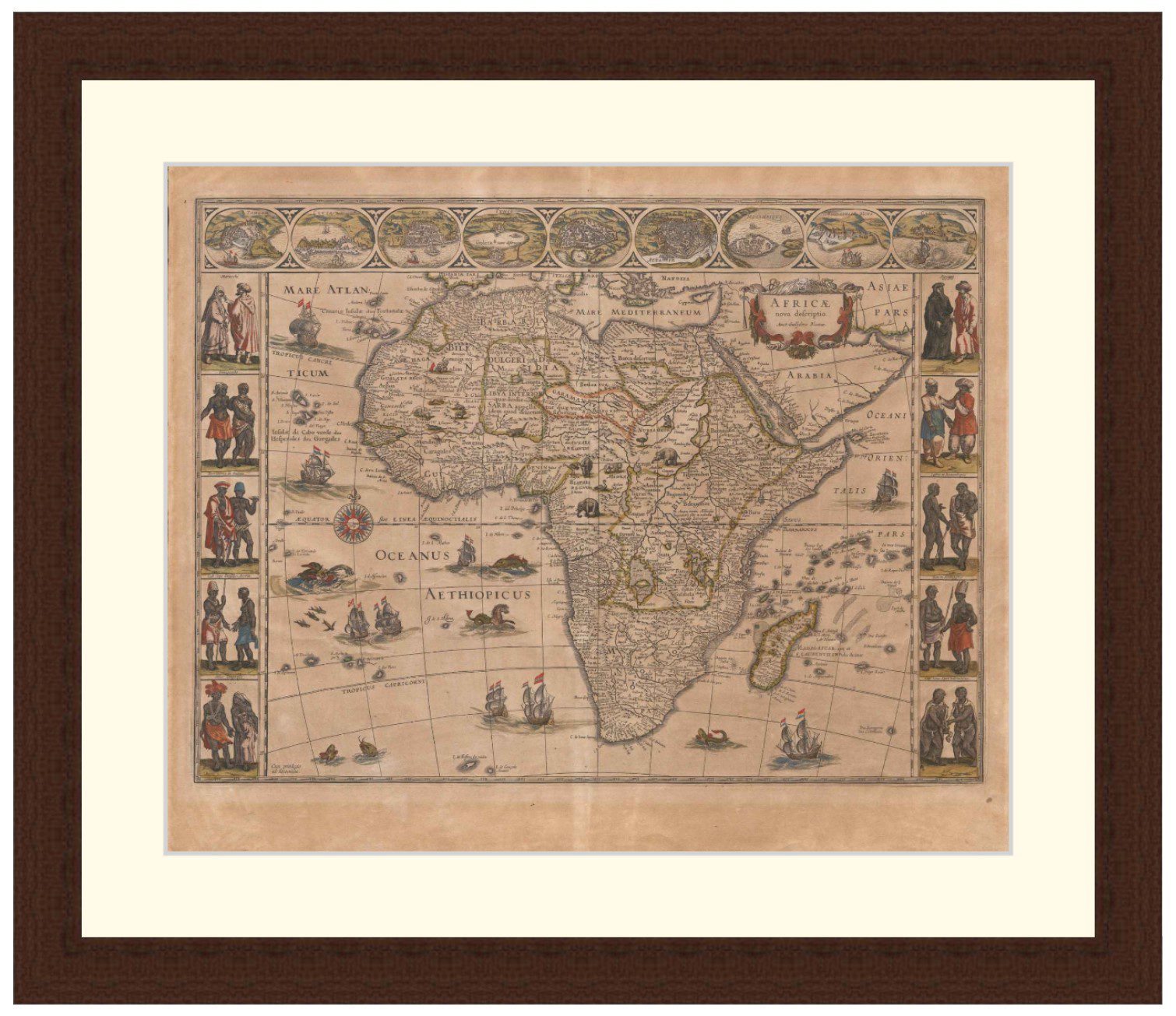

The Woman King is more than an action movie – it shines a light on the women warriors of Benin

Reading time: 6 minutes

The Woman King is a big-budget Hollywood movie that has been anticipated since 2018, when US star Viola Davis was announced as the lead in the story of the “amazons” of Dahomey. Rising South African star Thuso Mbedu also takes a key role in the film, which has premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival and is heading to cinemas worldwide.

Australia, Indonesia and Confrontation

Reading time: 4 minutes

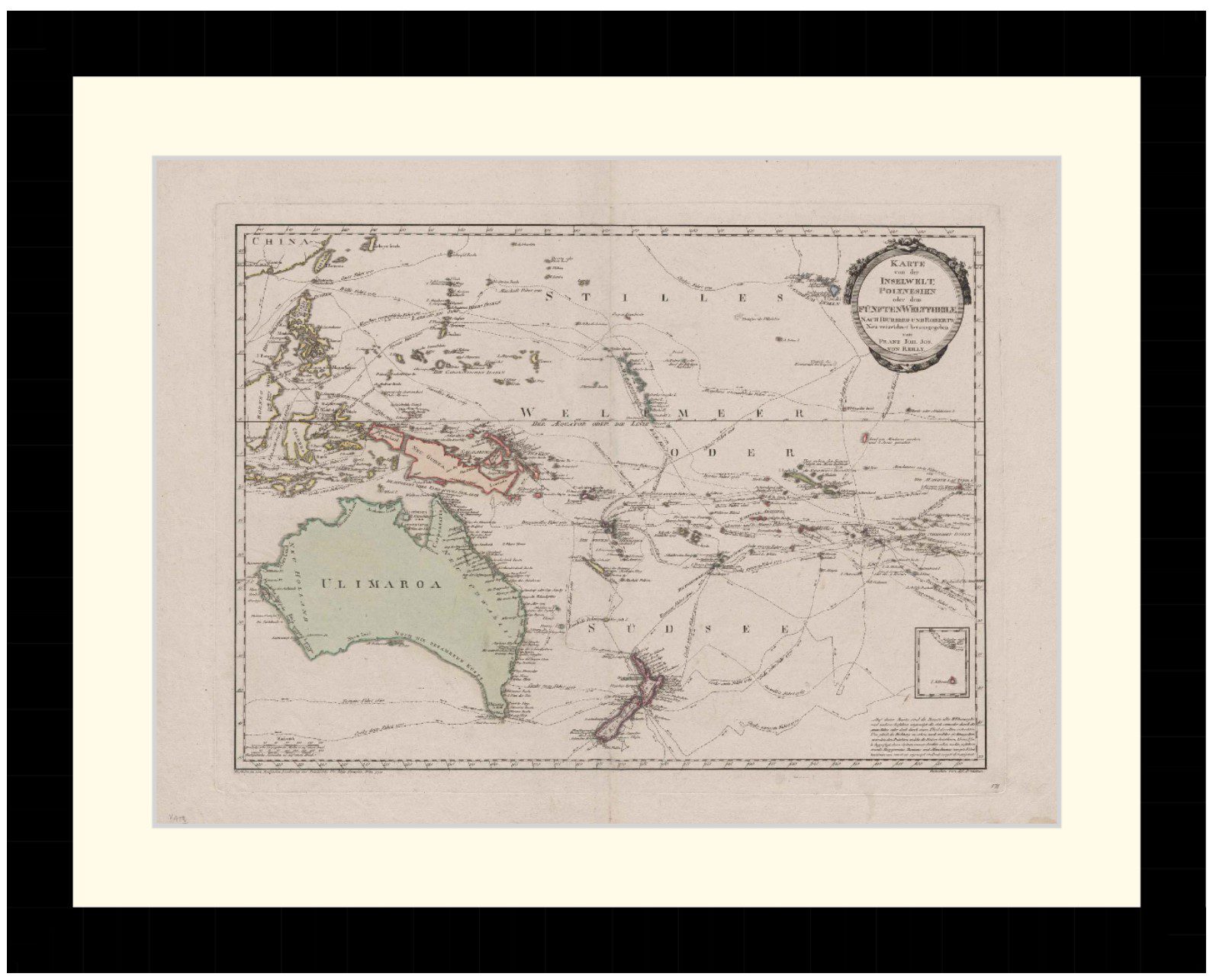

Between 1963 and 1966, Australian troops supported British and Malaysian forces who were opposing the Indonesian ‘Confrontation’ (Konfrontasi) of the new federation of Malaysia.

The Indonesian Confrontation (as it’s now officially designated) was a relatively small conflict instigated by Sukarno, soon wiped from the public mind and memory by the much larger war in Vietnam. But Jakarta’s provocative mixture of political rhetoric, diplomatic posturing, and low-level military engagements always carried the danger of escalation, threatening Australia’s national interests and complicating our alliance relationships.

The Beginning of the Middle Ages – Audiobook

THE BEGINNING OF THE MIDDLE AGES – AUDIOBOOK By Richard William Church (1815 – 1890) In 395 A.D. Theodosius, the last ruler of the undivided Roman Empire died. To his young and incompetent son, Honorius, he left the government of its western half. Honorius depended upon the great general, Stilicho, to withstand the Visigoths under Alaric. […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks