Reading time: 6 minutes

The Woman King is a big-budget Hollywood movie that has been anticipated since 2018, when US star Viola Davis was announced as the lead in the story of the “amazons” of Dahomey. Rising South African star Thuso Mbedu also takes a key role in the film, which has premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival and is heading to cinemas worldwide.

The action blockbuster is adding to renewed global interest in the historical women warriors of Dahomey, a kingdom that flourished in the 1700s and 1800s in what is today Benin in West Africa. The “amazons” were exceptionally skilful women warriors. They inspired fear and curiosity among locals and foreigners who had come to explore and colonise the territory. Protectors of the king, the anticolonial women warriors are referred to as Agoodjies in Fon, one of Benin’s many languages.

By Dominique Somda, University of Cape Town.

The Woman King is not the first time that Dahomey’s “amazons” have appeared in Hollywood productions lately. The mighty warriors were featured in the popular TV series Lovecraft Country (in an episode where Hippolyta Freeman, a black woman in pre-civil rights America, experiences a triumphant, cosmic journey of liberation). And there were the Dora Milaje, the Wakanda warriors in the blockbuster film Black Panther. Modelled on the Agoodjie, they are the protectors of Black Panther. Incarnations like these have helped bring the warriors of Dahomey into the popular culture spotlight.

On social media and in reviews the film is being celebrated as an example of “fierce” representations of black womanhood, so unlike dominant popular culture stereotypes. But who were these women – and how does their legacy resonate in Benin today?

A statue is unveiled

A colossal bronze monument called Amazon – created by Chinese sculptor Li Xiangqun – was unveiled in Cotonou in Benin on 30 July, the 62nd anniversary of the country’s independence from France. It depicts a young female warrior dressed in a belted tunic and armed with a shotgun and a short sword. Amazon joined two other new monuments erected as symbols of anticolonial resistance.

The statue follows an exhibition about the warriors held in Cotonou in 2018 and a new museum featuring them is expected to open in 2024 in Abomey, the former royal capital of the Dahomey kings.

The government of Benin appears to have tasked them with the dual responsibility of embodying a new female power and reviving national pride. The “amazons” have truly returned.

Who were the warriors?

Much has been written about these legendary women warriors. The explicit comparison to the Amazons, a mythological group of female hunters and soldiers in ancient Greece, was first made by European men encountering the Agoodjie in Dahomey in the 1700s. The “amazon” reference became common by the mid-1800s.

The female warriors encountered by explorers and traders in the Fon (Dahomey) kingdom inspired awe because of their military prowess and perceived gender-bending. Dahomey was one of many kingdoms in an area known as Aja-Yoruba (between present day Togo and south-west Nigeria). Its regional dominance spanned the 1700s and 1800s, when Dahomey went from being a mere supplier of slaves for the African kingdoms of Allada and Hueda (Ouidah) – a prominent port in the transatlantic slave trade – to becoming the main coastal broker.

The women warriors of Dahomey’s skills as combatants were admired and feared, all the more so when they were seen as transgressively emulating masculine aggression. They may have been seen as fighting as males. Yet, in the royal palace, their positions were akin to other women – wives, concubines and enslaved women.

The women warriors were not always fighting for the independence of their land. They fought in the various wars that the kings of Dahomey waged against its neighbours. They played an important role in conflicts and raids that led to the enslavement of many Africans. Cudjo Lewis (formerly known as Kossula), “the last survivor of the slave trade in the USA”, recalled, in an interview with anthropologist and novelist Zora Neale Hurston, the terrifying attack on his village and the female warriors that robbed him of his freedom.

Return of the queen

A real-life queen has, in the past decade, been restored in both history books and the hearts of Beninese people. Queen Tassi Hangbé reigned from 1716 to 1718 and is sometimes credited as founding the corps.

As a child growing up in Cotonou in the 1980s, I was not as familiar with her as I was with her twin brother and predecessor, King Akaba. For a long time, the rule of Hangbé was presented as a mere regency. One study explains that she wasn’t even part of the king’s list (the names of the various sovereigns of Dahomey) until the 1900s. Hers is the only female name featured in the dynasty. Hangbé has a complicated history. Her erasure was largely due to the efforts of Agadja, the royal twins’ younger brother and Hangbé’s successor.

The queen, though, might not have been a warrior or the founder of the “amazons”. According to a 1998 study, the institution of female hunters and warriors probably existed before the creation of the Dahomey kingdom in the 1700s. Historians have advanced the theory that Hangbé’s twinship with Akaba nonetheless led to a dualistic organisation of men and women across the kingdom. Male officers, for example, had their female counterparts, displaying an ideal of genders completing one another to form a whole.

Hangbé’s legacy is now illustrious. The Queen Hangbé Foundation (Fondation Reine Hangbe) proposes to restore the twin sister’s place in history and to fight to end violence against women. Although the new statue in Cotonou is rumoured to be inspired by her, the government is clear that the new statue favours no particular kingdom or ethnic group in Benin. Instead, the monument honours the resistance against gender-based violence and is dedicated to past and present Beninese female fighters. Benin has also recently passed a few important laws protecting women and their reproductive rights.

Disrupting the male order

The Dahomey “amazons” were exceptional, but heroic women warriors, queens and princesses leading armies and resisting colonial expansion existed elsewhere across the continent, such as Queen Nzinga in Angola and Queen Nana Yaa Asantewaa in Ghana. For some African feminists, African women have never been frail and defenceless. The feminisation of the spectacle of violence still presents an exhilarating sense of disruption in an often male-dominated historical order.

Thanks to the hype around The Woman King and the conversations it has begun to ignite, the movie will undoubtedly help to shed more light on the extraordinary legacies of the Agoodjies. Not exotic heroines, mythological figures or comic book characters, but all-too-real combatants of West Africa’s “slave coast”.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcast episodes about The Woman King

Articles you may also like

Polygon Wood – Podcast

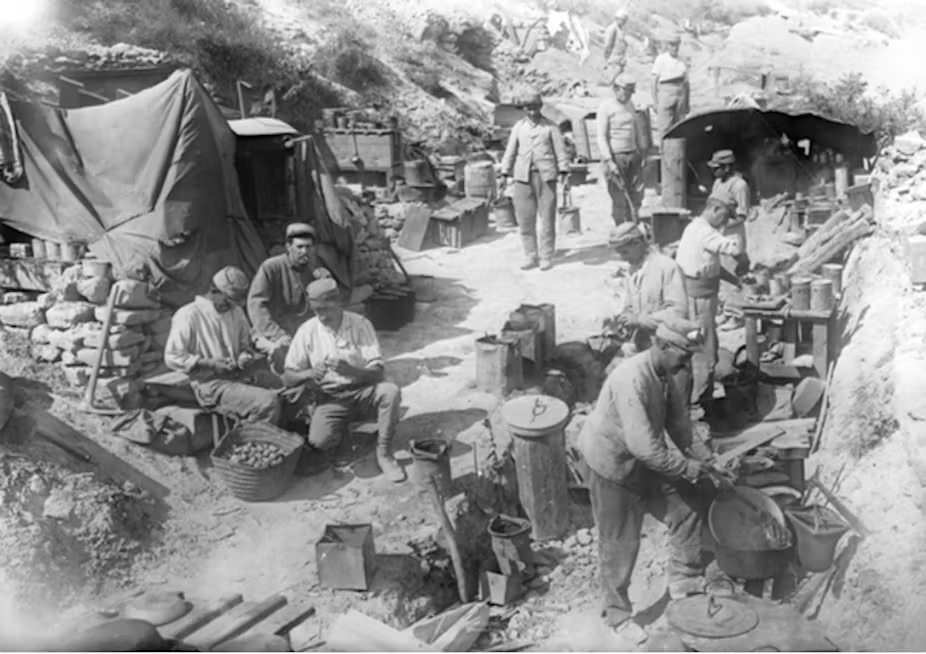

Following on from the success of the Battle of Menin Road, the 4th and 5th Australian Divisions took over from the 1st and 2nd Divisions to launch the attack at Polygon Wood. But the day before the battle is to commence, a strong German counter attack seized the ground which elements of the 15th Brigade were to attack from. It was a precarious situation which needed to be rectified immediately or else the whole attack could be thrown into confusion.

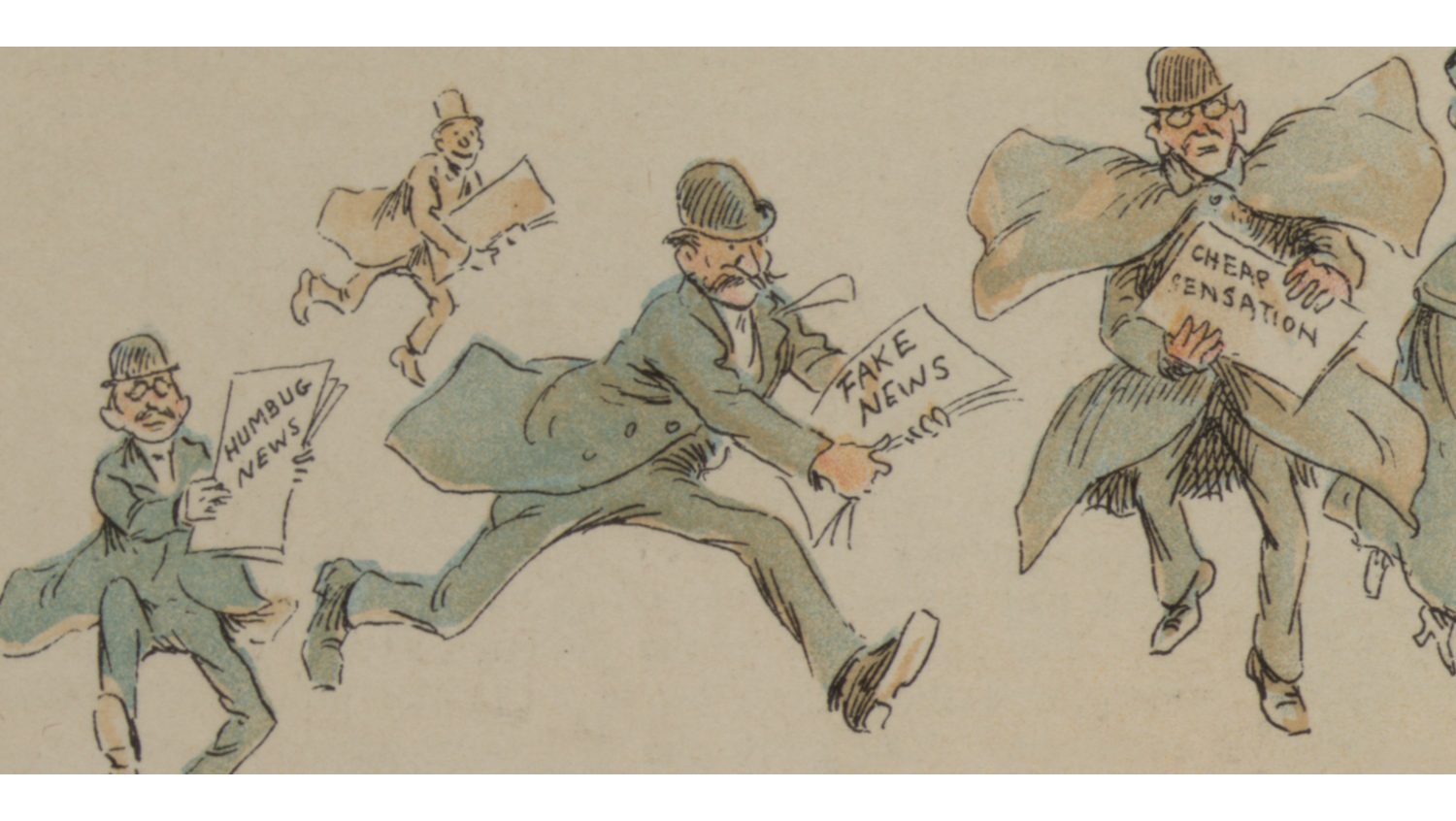

Why we don’t hear about the 10,000 French deaths at Gallipoli

Reading time: 6 minutes

With almost the same number of soldiers as the Anzacs – 79,000 – and similar death rates – close on 10,000 – French participation in the Gallipoli campaign could not occupy a more different place in national memory. What became a foundation myth in Australia as it also did in the Turkish Republic after 1923 was eventually forgotten in France.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.