DOMINO THEORY AND U.S. FOREIGN POLICY

When looking at the cold war and the way the United States went about its foreign policy, you can’t escape the influence of the so-called domino theory. This belief, a common one in American’s halls of power, stated that if one country fell to communism, the surrounding ones would, too. Was there any truth in this theory, though, or was it more scare mongering?

Reading time: 5 minutes

By Fergus O’Sullivan

First off, though, let’s make clear that the domino theory wasn’t really a theory. It’s not like there was a book published with that title, or some kind of policy paper of that name. Instead, it’s a phrase coined by historians and political scientists based on a quote by President Eisenhower in 1954, during a press conference about the future of Southeast Asia.

As the Siege of Dien Bien Phu turned more and more in favor of the Vietnamese in that year, and the French clearly were losing their grip on their former colony, Eisenhower in a press conference expressed worry that a victory by the Viet Minh would lead to a knock-on effect in the neighboring countries.

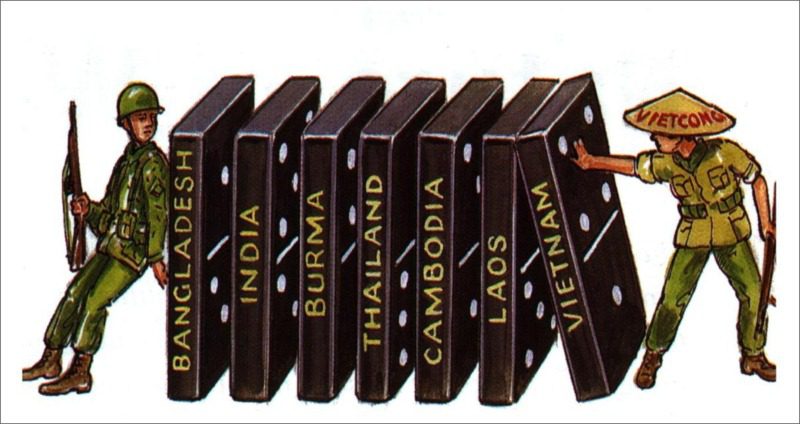

“You have broader considerations that might follow what you would call the ‘falling domino’ principle. You have a row of dominoes set up, you knock over the first one, and what will happen to the last one is a certainty that it will go over very quickly.”

Sorrowfully, no footage exists of that fateful speech, though this one is very similar in tone.

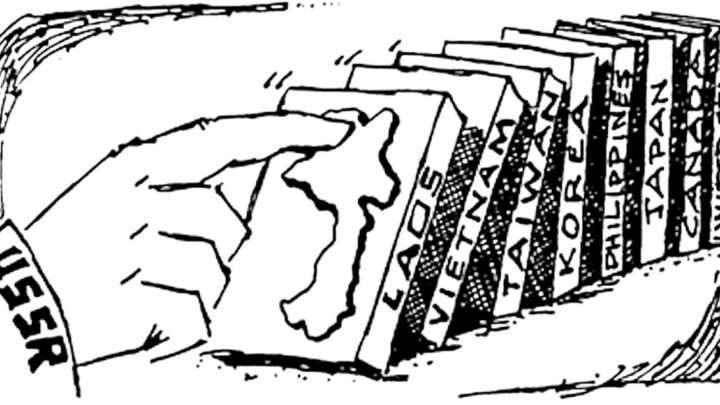

The first domino in this analogy would be Vietnam, though some would argue it’s China and Vietnam is the second domino. Once Saigon fell, Communists would take over neighboring countries like Thailand and Burma. Eisenhower even posited that Communist might take over countries like Indonesia and Japan as the ripples expanded further.

The First Domino: Vietnam

The natural conclusion is that to keep the last domino from falling, you need to prevent the first one from being tipped. Thus, the thinking went, stabilize Vietnam — by installing a vicious dictatorship firmly on the side of the west — and the neighboring countries will remain stable, too.

Though it was never stated outright, this idea drove the ever deepening American involvement in Vietnam (we have a number of articles on the Vietnam War if you’d like to know more), leading to more than a decade of bloodshed.

Interestingly enough, though, you can argue both in favor and against the domino theory. For example, as the North Vietnamese grew ever stronger, leading to the eventual defeat of the U.S., neighboring countries like Laos and, fatefully, Cambodia, did turn red. Whether this was through some kind of communist osmosis or because the U.S. expanded the scope of the war seems to be up to who’s reading the history.

Another strike against the domino theory is that no other dominoes fell after these two: Thailand and Burma didn’t turn, nor did Indonesia (despite flirting with Communism a little while fighting their war of independence against the Dutch). Japan dealt with left-wing terrorism in the form of the Nihon Sekigun, but at no time was in danger of being anything but a prosperous, capitalist nation.

Other Dominoes

The evidence is stacked against the domino theory, or at least having it as the main reason why countries would experience a revolution. Things like income equality and overall economic health seem to influence the rise of communism a lot more than sharing a border. If not, Finland would have been singing the Internationale somewhere in the mid-50s.

That didn’t prevent American policymakers from coming down hard on communists and socialists in other parts of the world, however. Often, it was seen as a way of curbing Soviet influence in that country, but in the background the fear that these movements could “infect” neighboring countries played its part, too.

One example is the coup in Chile, where the CIA — with Australian help — overthrew the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende and installed a brutal dictatorship under General Pinochet in its stead. Another is the civil war in Angola, where the U.S. aided the anti-Soviet forces in a bitter conflict that lasted more than 25 years.

In retrospect, the domino theory doesn’t hold much water, though to a country firmly in the grip of the Red Scare and its febrile paranoia it may have seemed plausible. Though it was never an overriding political philosophy, it did influence American foreign policy a great deal, and caused a lot of suffering where none was necessary.

Podcasts about this topic

Articles you may also like

How the National Guard became the go-to military force for riots and civil disturbances

The Pentagon has approved leaving 5,000 troops deployed indefinitely to protect the U.S. Capitol from domestic extremist threats, down from about 26,000 deployed after the Jan. 6 insurrection. The National Guard is a federally funded reserve force of the U.S. Army or Air Force based in states. These part-time citizen soldiers typically hold civilian jobs but can be activated […]

The Thucydides Trap: Vital lessons from ancient Greece for China and the US … or a load of old claptrap?

Reading time: 5 minutes

The so-called Thucydides Trap has become a staple of foreign policy commentary over the past decade or so, regularly invoked to frame the escalating rivalry between the United States and China.

Coined by political scientist Graham Allison — first in a 2012 Financial Times article and later developed in his 2017 book “Destined for War” — the phrase refers to a line from the ancient Greek historian Thucydides, who wrote in his “History of the Peloponnesian War,” “It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable.”

From micro to macro, Andrew Leigh’s accessible history covers the economic essentials

Reading time: 6 minutes

Andrew Leigh’s The Shortest History of Economics is the latest in a series of such histories, mostly focused on particular countries.

It begins with a striking mini-history of household lighting, focusing on the amount of labour required to produce the light now given off by a standard lightbulb: 58 hours for a wood fire, five hours for a candle based on animal fat, a few minutes for an early electric lightbulb, and less than one second for a modern light-emitting diode.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.