Reading time: 6 minutes

Christmas is literally “the mass for Christ”, the day on which Christians celebrate the birth of Jesus.

The western date for Jesus’ birth is quite arbitrary. It was chosen by Pope Leo I, bishop of Rome (440-461), to coincide with the Festival of the Saturnalia, when Romans worshipped Saturn, the sun god. This was the day of the solar equinox, the shortest day of the year in the northern hemisphere, which officially marked the halfway point of winter.

Leo thought it would distract his Roman congregation from sun worship by celebrating the feast of Christ’s birth on the same day. He described Jesus as the “new light”; an image of salvation, but timely in that the days began to lengthen from 25 December onwards.

By Bronwen Neil, Australian Catholic University

The date of the feast varies within Christian denominations. Western Christians celebrate the Nativity on a fixed date, 25 December. Some Eastern Orthodox Christians celebrate it on 6 January together with Epiphany, the revelation of the infant Jesus to three wise men. The Greek and Russian Orthodox celebrate Christmas on 7 January and Epiphany on 19 January.

Where did Christmas traditions originate?

It is true to say that the western Christmas began as a Christianised pagan feast. The Christmas tree is also a pagan symbol of fertility.

In northern countries, when the nights are long and cold, the feast of Christmas traditionally gave Christian people something to look forward to: rich food (reindeer if you are in Sweden, pork and lamb if you are in Greece), lots of candles, Catholic Mass at midnight or Protestant services on Christmas morning. Fir trees were brought inside and lit with candles as a symbol of the hope that spring would return with new crops and plentiful food.

The early church also celebrated Christ’s Resurrection in spring, the season of new life, since it coincided with the Jewish Passover feast on 14 Nisan, a date that depended on when the first full moon occurred in March or April. Many of our Easter symbols, like the bunny and the egg, are ancient fertility symbols. No one knows how chocolate got dragged in!

It is also an interesting coincidence that the Jewish Festival of Lights, Hanukkah, falls in November or December each year, and is celebrated with the lighting of the candelabra (menorah), traditional foods, games and gifts.

Where did Santa Claus come from?

The Santa Claus myth (spoiler alert: don’t read any further if you are under 10!) came from the legend of Saint Nicholas. Nicholas was a bishop in the city of Myra (in modern Turkey), who wanted to help poor young women get husbands. He left bags of money of the doorsteps of their family homes in secret, an anonymous gift to the poor to be used as a dowry.

For this he became known as the patron saint of virgins and children. Over time, his generosity was remembered by people giving gifts to children in secret on the feast of St Nicholas, celebrated on December 6 (in western Christian countries) and 19 December (in the eastern churches). His name in English became Clause, after the Dutch Sinterklaas. Dutch children and others in western Europe leave food out in a shoe or a clog for Nicholas’ horse on the eve of 6 December, and receive presents on the day of the feast.

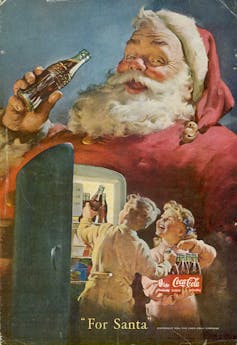

Our modern image of Santa Claus as a rotund gentleman of a certain age dressed in a red-and-white suit and matching hat comes from an incredibly successful marketing campaign by Coca-Cola in the 1930s. Since then, suburban Santas always dress in the image created by the Coke brand.

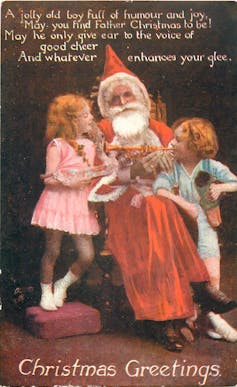

But this image comes from an earlier depiction of Father Christmas who had nothing to do with the American Santa Claus until the 1850s.

Until the Victorian era, when childhood was recognised as a separate stage of life, and the Christmas feast came to centre around children, Father Christmas, or Lord Christmas as he was also known, was the personification of a mid-winter feast of merrymaking for adults – and he brought no presents. He was useful as a symbol for Catholic-sympathising writers in the early 17th century who wanted to defend Christmas from attacks by the Puritans, radical Protestants who intended to ban the feast.

(For a Jewish perspective on the Wars of Religion, see Stephen Feldman’s book, Please Don’t Wish Me a Merry Christmas: A Critical History of the Separation of Church and State (1997).)

From the 1850s onwards, the English Father Christmas was depicted as a bearded old man wearing a long red robe trimmed with white fur and a pointed red hat, who brought gifts to good children. This image can be seen on English postcards from the early 20th century.

Christmas in the modern era

A lot of the significance of the original feast is lost when we in the southern hemisphere celebrate it in the middle of summer. A family barbecue at the beach cannot really capture the atmosphere of a cold and dark mid-winter.

This seems to be the main reason for the emergence of the alternative “Christmas in July”. Today we give presents to adults as well as kids on the eve or day of 25 December, and usually not anonymously. It would be interesting to see what would change if none of our gifts had name tags attached – Secret Santa at the office is based on the same concept.

Our gifts are also reminiscent of the tributes that the three Magi – who symbolise, according to tradition, the non-Jewish peoples – gave to the infant Jesus.

Incidentally, according to two of the four Gospels, Jesus was born in Bethlehem, but given the lack of corroborating evidence for a census there that year, it is now thought that Jesus was more likely born in Galilee, where he grew up. Bethlehem was significant for the Gospel writers as being the birthplace of King David 1,000 years earlier, and a royal city for the Jews.

The Magi gave Jesus gold, frankincense and myrrh, when they understood that the baby they were looking at was both human and the son of God. That mystery at least remains intact.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about the history of Christmas:

Articles you may also like:

Weekly History Quiz No.226

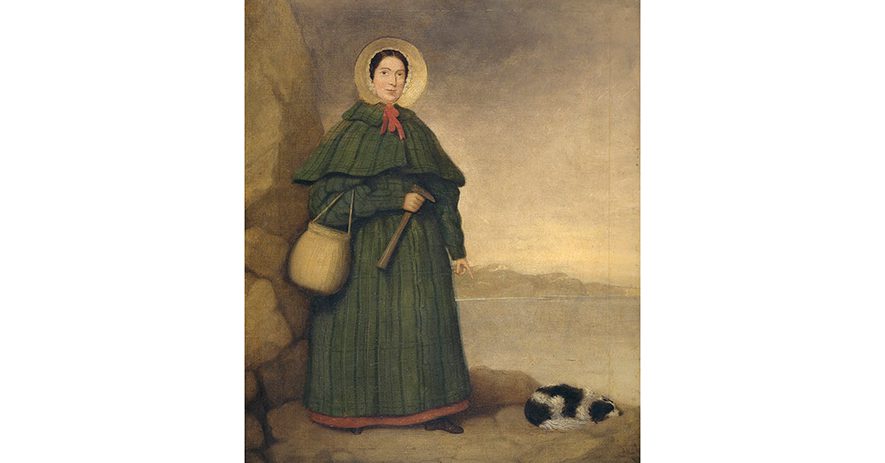

1. What was Mary Anning’s profession?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The Evolution of Modern Medicine – Audiobook

THE EVOLUTION OF MODERN MEDICINE – AUDIOBOOK By Sir William Osler (1849 – 1919) This is the manuscript of Sir William Osler’s lectures on the “Evolution of Modern Medicine,” delivered at Yale University in 1913. Here, the father of modern clinical medicine provides a brief introduction to the history of medicine from its origin to modern […]

General History Quiz 134

1. Ghana was previously which British colony?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.