Reading time: 20 minutes

Standing on a ferry chugging across Sydney Harbour, it’s still possible to imagine the city as it was in 1788 – before the span of the bridge, before the marinas and yachts, before buildings were planted onto that sloping, rocky landscape. Pockets of bush still reach down towards the water, where gums and angophoras curl around sandstone coves carved out by the sea water.

By Anna Clark, University of Technology Sydney

Ferries stop at Mosman, Manly and Milsons Point, where fishers share the wharf with boats and commuters. They perch on folding chairs next to white buckets of bait, or they plonk down on the wooden beams, rod in hand, their legs dangling over the edge as they sit.

Yet these places were also occupied, named and fished, long before “Sydney” appeared on any charts. And it’s at one of these harbour places, at Kay-ye-my, or perhaps Goram Bullagong (present-day Manly Cove and Mosman Bay), that our first story of Indigenous fishing is set. (After all, Kiarabilli or Kiarabily – the site of present-day Milsons Point and Kirribilli – is believed to translate into English as “good fishing spot”.)

Malgun – the amputation of the joint of a young girl’s left little finger – is one of many Aboriginal fishing rites that took place and was practised along much of the east coast of what’s now known as Australia. Across the continent, diverse and adaptable fishing practices, recipes and rituals were a cornerstone of Indigenous life at the time of first contact – and many remain so to this day.

Like keeparra (the knocking out of teeth) and scarification, malgun is a custom rich with significance, an offering to the spirits. In this case, the little girl would be forever linked with the fish she had literally fed. And as these girls grew into women, that connection to the underwater world was thought to offer good fortune and prowess with a fishing line.

It’s thought that malgun was also about the practicalities of fishing, since a shorter left pinky could apparently wind a hand line in more nimbly. The practice was observed among Aboriginal communities along the eastern seaboard of Australia (and featured around the country in various forms). But its meaning was frequently misunderstood in early colonial encounters and is still open for speculation.

To make the line, or currejun/garradjun, Gadigal fisherwomen used the bark or the tender fibres of young kurrajong trees, which they soaked and pounded or sometimes chewed, scraping off the outer layers with a shell. The pliable strands were then worked into fine strong thread. The women cast out their handlines and quickly drew them back in on the strike, hand over hand, before the fish could shake off the hook.

I like to picture the women sitting on a beach or around a fire as they made their string, humming, singing and chatting. They rolled the fibres along their thighs methodically, slowly turning them into lengths of delicate but durable fishing twine. Even the name of this beautiful and distinctive tree provides a valuable historical link to a time when fishing dominated the physical, social and cultural life of coastal Aboriginal peoples. What they sang and nattered about, while swatting mosquitoes and shooing away curious children, we can only guess.

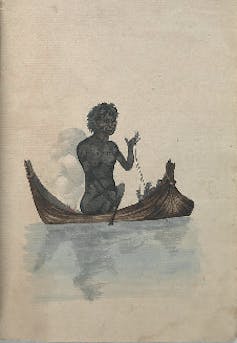

At the end of these lines, elegant fishhooks, or burra, made from carved abalone or turban shells were dropped over the side of their canoes, or nowies. In other parts of Australia, hooks made from a piece of tapered hardwood, bird talon or bone have also been found. These “nowies were nothing more than a large piece of bark tied up at both ends with vines”, described the British officer Watkin Tench in his account of early Sydney.

Despite the nowies’ apparent flimsiness, the fisherwomen were master skippers. They paddled across the bays and out through the Heads, waves slapping at the sides of their precarious little vessels. That mobility was essential for Aboriginal communities around the harbour – such as the Gadigal, Gayamaygal, Wangal, and Darramurragal – who needed to chase shoals and find new grounds if the fishing was quiet at particular times of the year. Small fires were lit in the nowie on a platform of clay and weed before the craft was launched into the water from a snug harbour cove.

Then the fisherwoman perched inside and paddled to a favourite spot or two, often with a baby cradled in her lap and an infant on her shoulders or crouched beside her. Out on the water, she chewed crustaceans and shellfish, spitting some out into the water before jigging her pearlescent hook up and down like a lure.

This sort of berleying was practised all around Australia in the hope of generating a bit more action – thousands of years before punctured tins of cheap cat food dropped off the back of a tinnie to attract fish became the norm. When the fisherwoman threw the line overboard, she waited for that strike and tug from a whiting, dory or snapper, which would be quickly hauled aboard and charred on the waiting fire. And she sang as she fished, as Grace Karskens describes in her wonderful book on colonial Sydney, her voice carrying across the bays and inlets and down through the water to the fish below.

Those fishing songs also captured the attention of colonists, such as the colonial judge advocate David Collins, who described seeing Carangarang and Kurúbarabúla (the sister and wife of Bennelong, respectively) return from a canoe trip “to procure fish” and they “were keeping time with their paddles, responsive to the words of a song, in which they joined with much good humour and harmony”.

Some, like the French explorer Louis de Freycinet, were so transfixed by the songs they overheard bouncing over the water they attempted to write them down in musical notation.

Fishing archives

While women were the anointed shellfish gatherers in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, as well as line fishers in the areas where that was practised, spearfishing was largely the preserve of men – and this continues to be the case today. Hunters stalked the water’s edge or stood in a canoe, looking for the telltale shadow of a dusky flathead or the flash of silver from a darting bream.

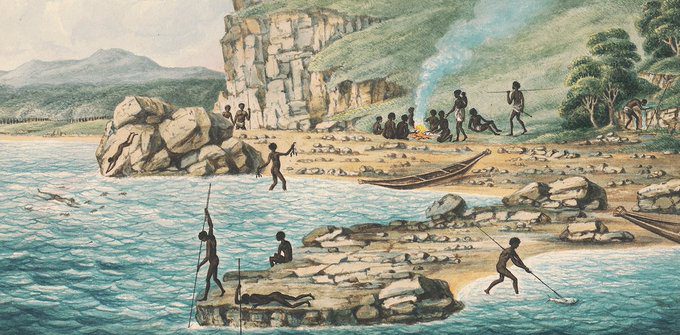

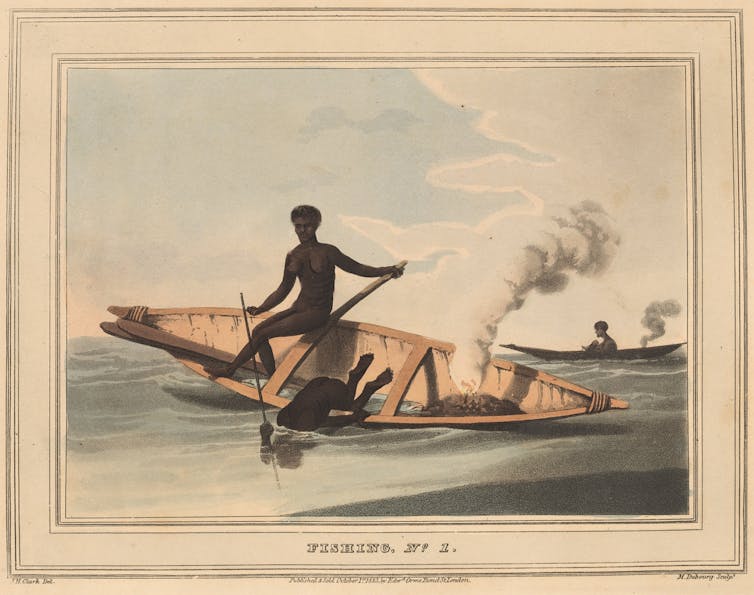

When the water was calm and clear enough, Aboriginal men around Warrane-Sydney Harbour and Kamay-Botany Bay were frequently seen lying across their nowies, faces fully submerged, peering through the cool blue with a spear at the ready. “This they do with such certainty, as rarely to miss their aim,” wrote the painter and engraver John Heaviside Clark in 1813.

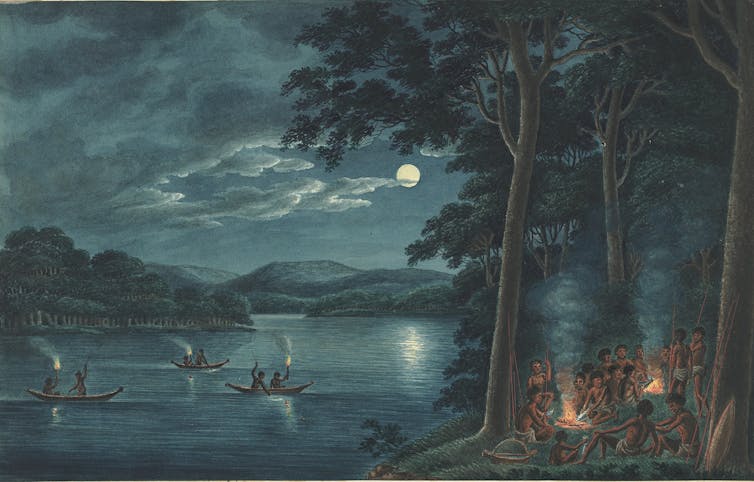

At night, Aboriginal fishermen took the canoes out onto the water with their flaming hand torches held aloft. The light lured the fish to the boat’s side, where they were speared by a barbed prong whittled out of bone, shell or hardwood. In the muddy mangroves of northern Australia, fires were sometimes lit on creek banks to attract barramundi, which swam towards the light and suffered the same fate.

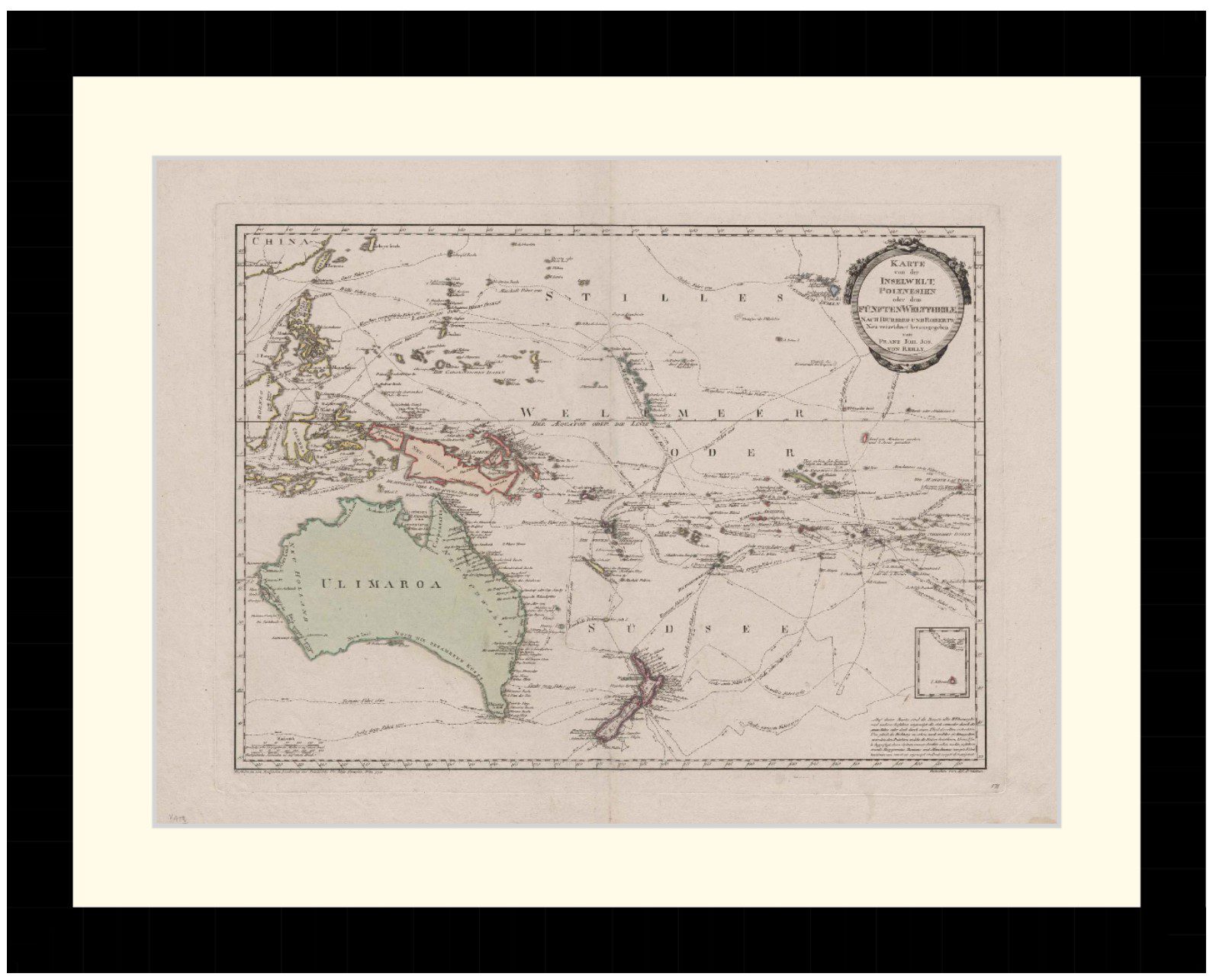

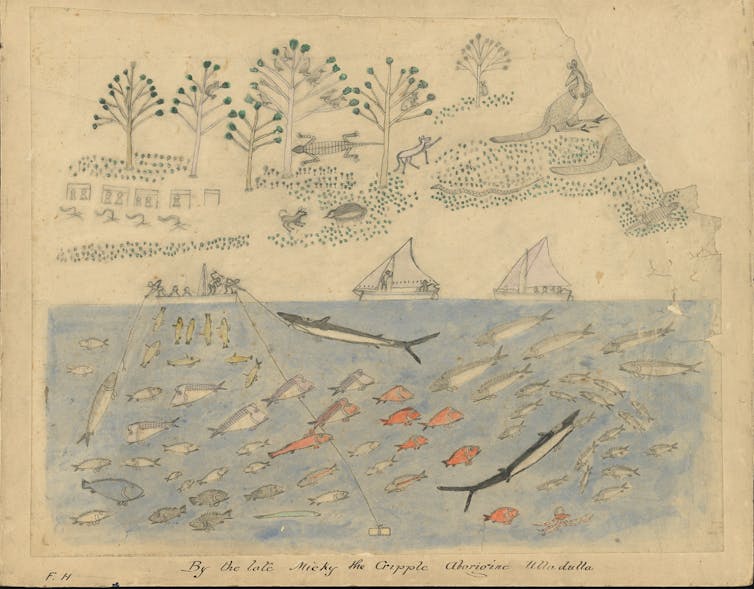

Beautiful images from the early days of the colony demonstrate the country we can still see traces of today: folds in the landscape as it stretches out across the horizon, the bush reaching right down to the water’s edge, protected sandy coves perfect for camping and fishing. They also show us the centrality of fishing to First Nations communities. These sources depict how Aboriginal people fished and what they caught, like a juicy snapper flailing on the end of a spear, or a fisherwoman managing both an infant and a fishing line in her nowie. The skill of these fishers and the abundance of fish are lasting impressions from these visual records.

While early colonial sketches and paintings give wonderful snapshots of Aboriginal fishers, they do so from a European perspective. Written accounts are similarly revealing, and we can be grateful for the faithful record of fishing practices and winning catches they’ve produced. But we can’t forget that these people viewed First Nations societies through a distinctly colonial lens.

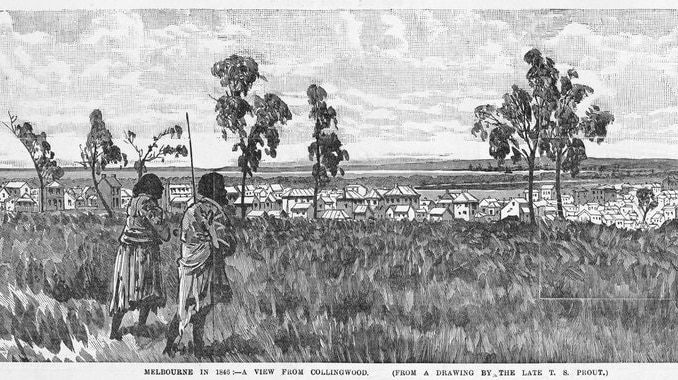

The early colonial view of Australia was mostly curious and enlightened, and colonists were often captivated by the extraordinary skills of Aboriginal fishers, as well as their depth of knowledge about their Country. Yet they were also people of their time, who saw the British expansion in Australia as inevitable, and viewed Country as a resource awaiting exploitation.

Sometimes, vital Indigenous perspectives creep in. Scars on the mighty trunks of river red gums, or canoe trees, along the banks and flood plains of the Murray River reveal an Aboriginal presence long before any European record. Enormous engravings of whales, fish and sharks etched into sandstone platforms around Sydney and into the rugged iron ore of Murujuga-Burrup Peninsula in Western Australia have a provenance thousands of years older than any colonial etching or journal entry. Elaborate fish traps across the continent and the Torres Strait demonstrate intricate knowledge of seasonal and tidal fish aggregations.

Paintings in smoke-stained caves across northern Australia show equally distinctive Aboriginal readings of fishy feats and feasts. And the remnants of literally millions of seafood meals can be seen in middens around the continent that cascade through dirt, sand and mud at the water’s edge.

These Indigenous archives give us a glimpse into fishing before European colonisation. They also reveal the ingenuity of pre-industrial First Nations communities, long before fish finders, weather apps and soft plastics.

Remnants of vast, curving fish traps, or Ngunnhu, made from river stones still lie near Brewarrina in central New South Wales. (There were even more Ngunnhu once, until they were pushed aside to make way for paddle-steamers taking the wool clip down to Adelaide in the late 19th century.)

In the early spring or during a large flow of fresh water after heavy rains, enormous numbers of fish would travel upriver, swelling the eddies and currents with a mass of writhing tails and fins. Aboriginal fishers – men and women from the Ngemba, Wonkamurra, Wailwan and Gomeroi nations – kept watch from grassy embankments above the river and, as soon as enough fish had entered the labyrinth of traps, they rolled large rocks across the openings, ensnaring them for a seasonal fish feast.

These traps and weirs were also an early form of fisheries management – well before government regulations and research organisations – and remnants can be seen right across central and western New South Wales. Juvenile fish were carried in curved wooden coolamons and released behind the barriers on the smaller tributaries as a way of boosting stocks and ensuring fish for seasons to come.

The Budj Bim eel traps at Lake Condah in southwest Victoria were designed, built and maintained by the Gunditjmara people, who operated the series of channels, locks and weirs. Built at least 6,600 years ago, the traps have been redeveloped several times over several centuries, and they demonstrate an ecologically sustainable management of this freshwater eel fishery that was adapted and lasted for thousands of years. What’s more, they can still be seen today.

Other traps were less permanent, but just as effective. When particular waterholes were low in the Baaka-Barwon–Darling river system in New South Wales, Barkindji people living along the river used wooden stakes, logs and sometimes stones to build shallow pens that trapped fish, yabbies and eels for easy pickings.

The ill-fated explorer William John Wills described a similar “arrangement for catching fish” somewhere north of Birdsville around the Georgina River, where he camped with Robert O’Hara Burke and the rest of their party in January 1861. The trap consisted of “a small oval mud paddock about 12 feet by 8 feet, the sides of which were about nine inches above the bottom of the hole,” he wrote. The “top of the fence” was “covered with long grass, so arranged that the ends of the blades overhung scantily by several inches the sides of the hole.”

Periods of drought and seasonal dry weather could change rivers from torrential, turgid flows to the most meagre trickle – a chain of muddy holes through the landscape. Across northern Australia, seasons of wet and dry charged the landscape with weather cycles that pushed water across the floodplains of the northern savanna in great sheets, and then inevitably dried them out again.

But even low water could mean good fishing, since the fish would be forced to aggregate in particular waterholes, where they could be readily trapped and caught. While the grass might be parched and brittle up on the banks, the water below was teeming with life; that was the time when Aboriginal people walked along the creek bottom, muddying the water and forcing the fish to rise and take in air where they were easily speared, clubbed or netted.

In the Kimberley, when the dry season came and the floodwaters finally receded, rolls of spinifex were used to entangle fish that had been trapped in the remaining waterholes.

Fishing objects and artefacts

Artefacts such as spears, hooks and nets also help reconstruct some of the changing ways and means of Indigenous fishing that predate European colonisation and continue to be used and modified long after it. These relics are as beautiful as they were effective.

Kangaroo tail tendon was used to bind fishhooks in northern Australia. The prongs of spears (fish gigs or fizgigs) were hardened and polished and then attached to the long shaft using pieces of thread daubed with resin.

Meanwhile, nets made from lengths of finely twisted twine were so carefully knotted together that when Governor Phillip showed them to the white women in the colony, the elegant loops reminded them of English lace. Those nets came in all shapes and sizes and were highly prized possessions. To strengthen the nets’ fishing powers, Aboriginal people sang to them: their music and words, literally singing in the fish, were like charms for the Dreaming that cascaded through the weave.

In the area of what’s now known as Sydney, coastal tribes used small hoop nets to pick up lobsters, which hid in underwater crevasses on the edge of the harbour and along the beachside cliffs. Catch-and-cast nets trapped small numbers of fish in creeks and waterholes near the coast and could also be used to carry a feed of fish as families walked back to their camps along the well-worn walking tracks.

Further inland, Aboriginal people made large woven river nets, which could be held by hand or propped up along the bank. Once fixed in place, groups of people waded through the murky water, loudly beating the surface and driving the startled fish into the mesh.

The nets were usually about four metres long and one metre deep – sizeable enough, considering every strand was gathered, spun and woven by hand. But one extraordinary account from the explorer Charles Sturt described how his exploration party on the Wambuul-Macquarie River in western New South Wales discovered a fishing net some 90 metres long in a Wiradjuri village they came across.

Other fishing methods have been recorded and described in oral histories, or they’ve been passed down and are practised still. These practices are a form of embodied or “living archives”, which is how we know about them today. Stories of women diving deep underwater for shellfish, walking out across the rocks at low tide pulling off abalone, or wading through billabongs to pick up turtles, are common in accounts from the time and these practices are still maintained by many Indigenous communities around Australia and the Torres Strait Islands.

Given such longstanding fishing connections, “sea rights” have been increasingly recognised by governments in legislating fisheries management. Back on the beach or riverbank, a fire is inevitably on the go in anticipation of a fresh catch. The fish is usually chucked on whole and eaten.

Some of the environmental knowledge used by Traditional Owners seems astonishing in today’s context of mass-produced fishing lures and frozen bait from the local servo. One account from northern Australia described a particularly large Golden Orb spider carefully killed to preserve its abdomen, which was then gently squeezed to milk its adhesive goo. Small fish, attracted to the carcass, would then get stuck to the dead spider before being delicately lifted ashore by nimble hands.

Fish poisoning, using various berries, roots, leaves and stems, was also common throughout Australia. In the Kimberley around the Goonoonoorrang-Ord River in Western Australia, Traditional Owners such as the Miriuwung, Kuluwaring, Gajerrabeng used crushed leaves from the freshwater mangrove (malawarn) to poison their prey, sweeping branches through the water until stunned fish started floating belly up.

Along the east coast it was wattle leaves that did the damage. The sunny, fragrant puffballs of two common acacias (Acacia implexa and Acacia longifolia) belie their potency as a fish poison. Once absorbed through the gills, antigens from the bruised leaves were quickly catastrophic for fish in little waterholes and billabongs. There are even accounts of eels gliding out of the water and into the bush along the Clarence River in northern New South Wales (known as Boorimbah to the Bundjalung and Ngunitiji to the Yaygir) in an attempt to escape poisoning from Aboriginal fishers.

Although these poisoning methods apparently had no effect on the edibility of the fish, the trick was to carefully manage the immersion of these toxic branches in the water – giving just enough poison to stun the fish , but not enough to knock out the whole waterhole.

That intimate knowledge and understanding of Country and its seasons wasn’t readily apparent to the early colonists. Watkin Tench was so perplexed by the unpredictability of fishing in Australia that he complained about spending all night out on Sydney Harbour for little result. The “universal voice of all professed fishermen”, he lamented in the 1790s in A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson, was that they had “never fished in a country where success was so precarious and uncertain”.

It was knowledge that came slowly to the colonists, over several generations. William Scott, the New South Wales colonial astronomer from 1856 to 1862, observed how the Worimi people were able to anticipate fishing seasons around Port Stephens on the New South Wales Mid North Coast. “By some unerring instinct the blacks knew within a day when the first of the great shoals [of sea mullet] would appear through the heads,” he explained.

For the Yolŋu in Arnhem Land, flowering of stringybark trees coincides with the shrinking of waterholes, where fish can be more readily netted and speared, or poisoned. And when the Dharawal people of the Kamay and Shoalhaven region in New South Wales see the golden wattle flowers of the Kai’arrewan (Acacia binervia), they know that the fish will be running in the rivers and prawns will be schooling in estuarine shallows.

In Queensland the movement and population of particular fish species have their own corresponding sign on land. The extent of the annual sea-mullet run in the cool winter months can be predicted by the numbers of rainbow lorikeets in late autumn; if magpies are scarce in winter, numbers of luderick will also be low; and when the bush is ablaze with the fragrant sunny blooms of coastal wattle in early spring, surging schools of tailor can be expected just offshore. Although climate change may shift these fishing markers in the natural world.

This knowledge was acquired by Australia’s Indigenous peoples through generations of observation and practice. What’s more, that deep understanding was as much about the spirit world as the natural. Neither can be properly comprehended without reference to the other – although our own contemporary insights are often sketchy, since the sporadic observations of colonists are frequently the only available historical sources we have of Indigenous fishing practices, which had been developed over millennia.

Practical understanding was intimately entwined with spiritual readings of the land. First Nations Dreamings are systems of cultural values and observations: they created the world and are reflected in day-to-day observations of that life. These “spiritscapes”, as the archaeologist Ian McNiven has called them, infused Country with cosmology. The natural and spirit worlds were one and the same. Country wasn’t inanimate – it could feel and do. And for many Aboriginal people to this day, that knowledge remains a shaping, dynamic belief system.

There are accounts on the South Australian coastline of Aboriginal people ritually singing in dolphins or sharks to herd fish into man-made or natural enclosures on the Eyre and Yorke Peninsulas. In Twofold Bay, on Yuin Country in southern New South Wales, dolphins were similarly used to herd fish, and a totemic bond between killer whales and Aboriginal people was also observed and documented.

Why did Aboriginal communities around Sydney avoid eating sharks and stingrays? The water was full of them, but they were only ever eaten during times of food scarcity. William Bradley, a first lieutenant on the First Fleet, observed Aboriginal people catching “jew fish, snapper, mullet, mackerel, whiting, dory, rock cod and leatherjacket” throughout the summer, but they didn’t keep the sharks or rays. “There are great numbers of the sting ray and shark, both of which I have seen the natives throw away when given to them and often refuse them when offered”, he noted.

In Lutruwita-Tasmania, archaeological excavations of middens suggest Palawa people mysteriously avoided eating finfish altogether for the 3000 years prior to colonisation, hunting mammals and scavenging shellfish instead. Was it spiritual? A response to some sort of poisoning event? Or an economic decision to harvest easier resources (such as seals and abalone)? Did the community lose their knowledge of fishing, as some have argued? Or did they perhaps dispose of the bones somewhere else? No one really knows.

Some forms of Indigenous fishing inevitably became lost as Traditional Owners were dispossessed and disenfranchised of their lands and fisheries following the expansion of the colonial frontier post-1788. Many Indigenous practices were eventually superseded by new technologies. Other Indigenous fishers became active in the establishment of the commercial fishing industry in Australia, maintaining strong links to traditional knowledges, as well as adapting to modern fishing approaches and technologies.

Indigenous peoples have played and continue to play a prominent role in the history of Australian fishing.

Despite the ruptures of colonisation, the cultural and social cleavages wrought by disease, as well as frontier violence and dispossession, they remain a visible and vital part of Australian fishing culture as commercial and recreational fishers, industry partners and Traditional Owners of the vast natural resource that is Australia’s fisheries.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about indigenous fishing

Articles you may also like

From the bookshelf: ‘The Scrap Iron Flotilla’

Reading time: 4 minutes

Mike Carlton has emerged as a gifted historian of Australia’s outstanding naval contributions in two world wars. He polishes this reputation in his new book, The Scrap Iron Flotilla: five valiant destroyers and the Australian war in the Mediterranean. Carlton has always been persuasive in print. His earlier books, Cruiser on the wartime record of HMAS Perth, and First victory 1914, detailing HMAS Sydney’s destruction of the German raider Emden, suggested both the enthusiasm for and appreciation of Australian naval history which the author has in abundance.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.