Reading time: 12 minutes

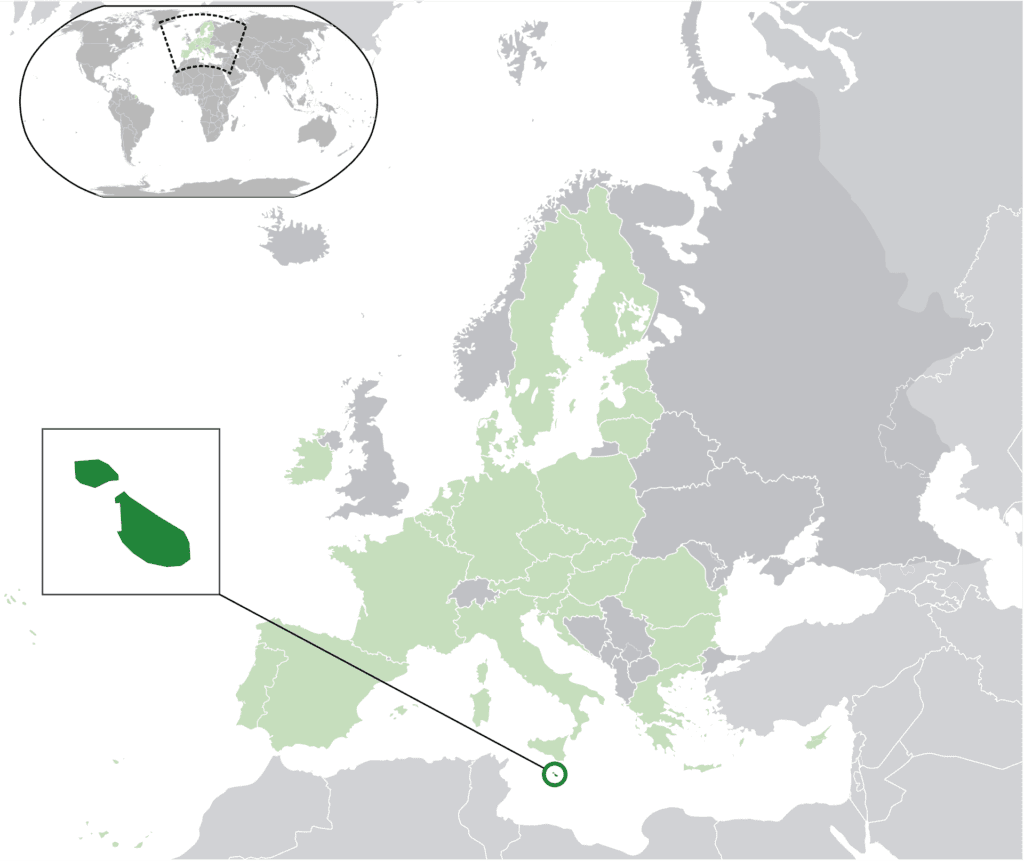

The Siege of Malta in the Second World War, which lasted from June 1940 until November 1942, was a linchpin of the war. Had Malta fallen to the Axis, the war may have concluded very differently. Australian soldiers, sailors, and airmen played a crucial part in defending the island, in this article we explore how they experienced it.

By Fergus O’Sullivan

Like many of our article about Australians in the Mediterranean in World War Two, this article draws heavily on the Australians at War Film Archive which contains hundreds of eyewitness accounts of Australian servicemen and women. We recommend anybody delve into it for an idea what the war was like for the people who fought in it.

The value of Malta

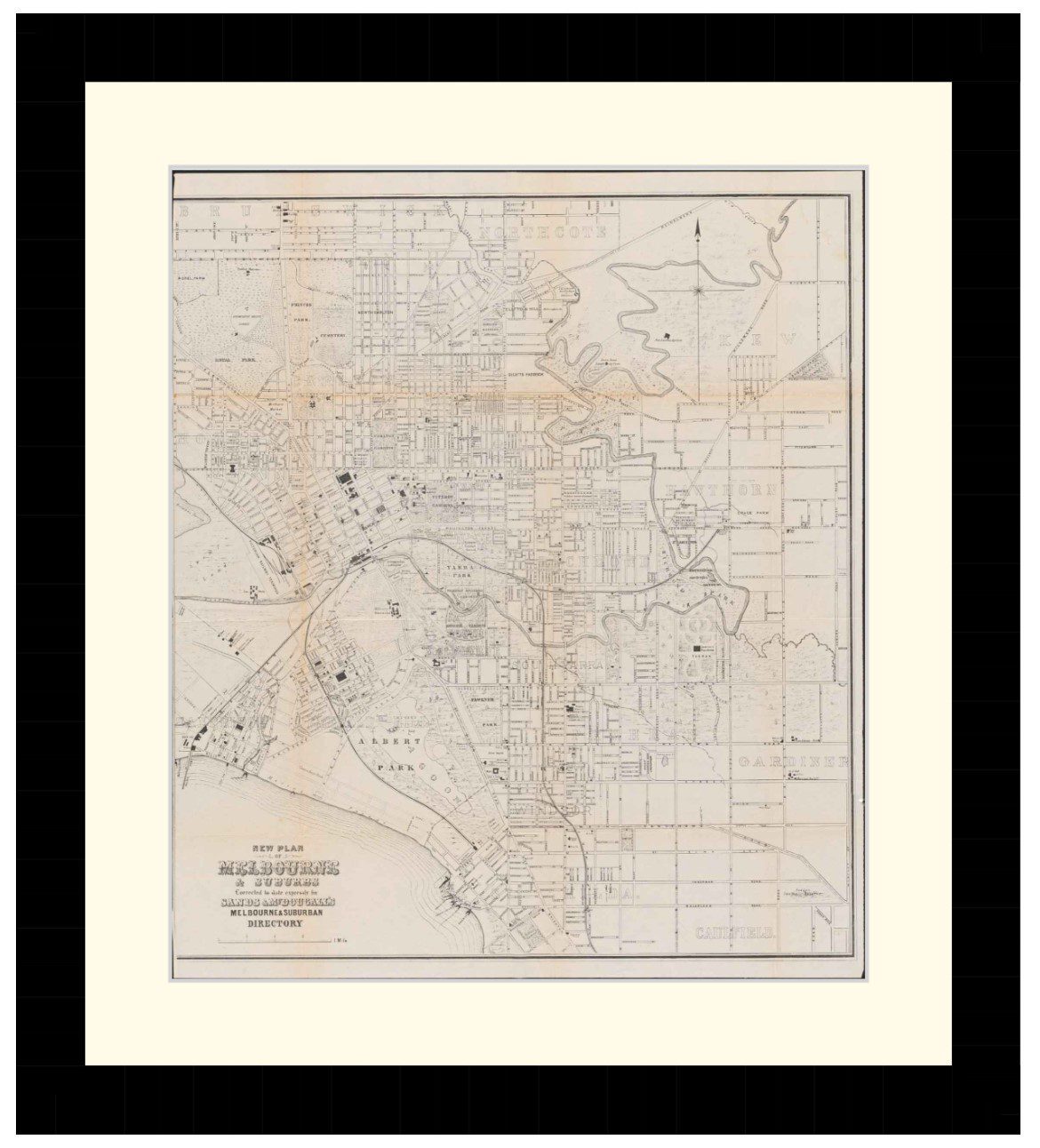

Malta was originally occupied by the British due to its amazing strategic location. Situated in the narrow straight between Sicily and Tunisia, it gives control over any shipping going between the Eastern and Western Mediterranean, and vice versa.

As an airbase, it gives control over an area stretching from the deep Tunisian desert, a large chunk of Libya and the lower part of the Italian boot, not to mention all of Sicily, even as far as Albania.

In the words of Oriel Ramsay from Perth, a sailor aboard the HMAS Sydney who also featured in our article on the battle of Cape Spada, it’s location made Malta the “garage for the Mediterranean fleet.” British-born submariner Francis Selby confirms this, and it’s clear from his testimony that Malta also was the submarine base for the Med, with subs laying up there for maintenance between patrols.

Scanning the skies

Malta wasn’t just a hub for materiel, either, it also housed a radar station. In his account, Walter Preen from Boulder, Western Australia had this to say: “If we’d lost Malta, we’d have lost the Mediterranean… even [during] the Battle of Britain… they gave Malta priority with radar, so their radar could pick up the raiders planes coming quicker than the English could pick them up coming from France… if we lost that we were gone. We’d have lost North Africa, possibly Syria, Iraq and all that oil area could have gone… that’s why Malta was so valuable.”

Max Middleton from Western Australia, a sailor in the scrap iron flotilla, recalls guarding the radar station while his ship was laid up for maintenance, but never really being told what they were guarding: “there was this radar station sitting on top of a rather high hill on the northern side of Malta and we were sent out there to just patrol and guard it and we never saw it and we didn’t know what was going on we were just guard.”

Defending Malta

Whether or not the Axis knew about the radar installation is unclear, but even without it they had reason enough to conquer the island. An early attack plan put together by the Italians in late 1940 may have been successful, however this was called off at the last minute for unclear reasons. The likeliest explanation is that Italian intelligence overestimated the island’s defences and the assault was called off.

A later German plan, called Herkules, involved dropping paratroopers on the island. This was cancelled, however, after the battle for Crete where the German fallschirmjäger suffered heavy casualties without making the kind of decisive impact Berlin expected.

Mainstream historians and many of the Australians featured in the Film Archive are of the opinion that either attack would have had a decent chance of success. Between the start of hostilities with Italy in June 1940 until April 1941, when the British were forced to get their act together as the Germans joined the war in North Africa, the defences of the island were poor, to say the least.

For example, according to Mr. Ramsay. in mid-1940 there were only three RAF planes in Malta. All three were obsolete Gloster Gladiator biplanes and were named Faith, Hope and Charity. Unsurprisingly, these didn’t put up much of a fight most of the time (read about an important exception in our article about the fight for Malta’s survival), meaning that any convoys coming to resupply Malta were easy pickings for the Italians.

According to Mr. Ramsay, most attacks on convoys were carried out by the Italian air force rather than the navy. The attrition rate was high, with Mr. Ramsay recalling that one convoy that started out with 53 ships “only about ten of them got through” to Malta.

The Siege

This situation, unsurprisingly led to massive shortages of everything on the island. People went hungry, something every RAAF pilot in Malta mentions. In his interview, Robert Cock from Adelaide emphatically states that “the Maltese were starving,” and George Paliser says that poor food caused dysentery, trench mouth, and other illnesses among both military and civilian populations. Robert Asker from Melbourne also says there were no cigarettes on the island.

This lack of air power also meant that the Italians had free rein to bomb Malta whenever they wanted. Every single source in the Film Archive mentions the heavy, almost incessant bombing. As Valletta, Malta’s capital, was mainly constructed out of the local limestone, this meant that during bombing raids razor-sharp fragments of rock would fly around, causing injuries to anybody unlucky enough to catch a shard.

Hiding in the catacombs

As a result, most of the people on the island, whether they were civilians or servicemen, would run to the catacombs that criss-crossed the cliffs Valletta is built on. Though this kept people safe from bombs, water would seep through the limestone, making it so most caves had a few centimetres of water in them. As a result, according to Mr. Cock, many Maltese, including the children, developed trench foot.

Between the bombing and the lack of food, Thomas Martin from Sydney, says the Maltese became very anti-Italian even though the islanders often had Italian roots themselves. Mr. Middleton even remembers a little ditty children used to sing after the all-clear was given: “raiders passed, kiss my arse, up Mussolini.” Mr. Middleton makes clear, though, they didn’t sing “up.”

The bombing would continue until the very end of the siege in late 1942, even after the RAF flew in the 249 squadron armed with Hurricane fighters in May 1941. Mr. Paliser was a pilot in that squadron and recalls that “it was raid, after raid, after raid. We were scramble, scramble, scramble.”

Stukas

Much of the fighting done by the RAF was with the Luftwaffe’s Stukas as they came low enough for the Hurricanes to engage. In the words of Clarence Singe from Maryborough, “Stukas, they were dive bombers. You’d think the Stukas were gone, they’d fly right over and you’d think they’re gone, and they’d flip right over on their back and down they’d come.”

These kinds of tactics were tough to defend against, but the pilots could give it a shot. However, the Italian air force had chosen a different tactic. Mr. Martin says the Italians would fly over very high, the Hurricanes would take off and fly around, but wouldn’t be able to engage as they simply could not make that kind of altitude in time. This made preventing bombardment tough for the defenders.

At sea, however, it was a different story. Arnold Coleman from Towoomba says that: “At night time we had U-boats, at daytime we had the bombers, the Stukas. The Stukas were the worst, there used to be three of them and they used to circle over the top and they used to take it in turns to come down. They were playing fair dinkum the Germans, but the old dagos [Italians], they never bothered you, they used to bomb at about thirty five thousand feet, you had plenty of time because as soon as you saw the bomb leave you’d just flip and away you’d go.”

Bombs from on high

Clem Higgins, who was interviewed by the Australians at War project as a veteran of the Vietnam War but was present for the Siege of Malta owing to his father being posted in the garrison, tells a harrowing tale of high-altitude bombing. One night, his dog Bonzo started barking and out of a feeling of unease his mother led them to the shelter despite there being no alarm. A few minutes a bomb fell and collapsed part of the house, including over the beds where he and his brother had been sleeping just a few minutes earlier. No wonder Mr. Higgins recalls the dog fondly.

Still, this kind of constant bombardment must take its toll. A good example is Mr. Cock, who even decades after the siege ended is still quite sharp during his interview. He recalls talking to a friend at the time: “From what you’ve been telling me about being in Malta it doesn’t sound like there’s much future in it.” And I said, “You’re darn sure. Dead right.”

In the next breath he tells of the lack of food, but also a lack of materiel. For instance, a fellow pilot was lost during a foray and his commanding officer forbade a search party simply because they couldn’t spare the equipment. Mr. Cock seems bitter, still.

Turning it around

Even though the Axis forces tried to wear the defenders down, slowly but surely things were turning around for Malta. More and better equipment came in, and the garrison was strengthened. Mr. Asker recalls how the beaches were fortified and thinks any attacker would have lost a lot of troops in an attack, whether by sea or air.

It also seems the Maltese would have made life hard for any invader. Mr. Higgins remembers that a German pilot who parachuted onto the island after having his plane shot down had to be saved from an angry mob by British soldiers. Whether Malta would have been another Crete (the Cretan resistance was no joke) we’ll never know, but hanging on to the island would have been tough.

Over the course of 1942, the bombing let up ever so slightly as the British RAF and Royal Navy started pushing more and more against the Axis — with several of the interviewed pilots also mentioning the difference the Spitfire fighter made against enemy bombers. Many of the pilots interviewed also say that they started more and more runs against targets in Sicily and Italy, as well as bombing campaigns against the enemies’ navies and troops in North Africa.

Throughout the rest of the war, Malta remained a vital hub in the Mediterranean, serving as garage for the fleet as well as an aircraft carrier. The shared suffering influences relations between Malta and Australia to this day, with a strong bond between the two nations.

The Siege of Malta is one of the lesser-known episodes of World War Two, but that didn’t make it any less vital to the war effort. Many of the most well-known victories in North Africa, like the Second Battle of El Alamein, would have been impossible without the logistical support coming from the tiny island. If you’d like to visit Malta and see for yourself what the siege may have been like, we have a full guide to all the important sites.

Podcasts about Australians in the Mediterranean during WWII

Articles you may also like

How War with Spain Created the Dutch Colonial Empire

The Dutch colonial empire was a large collection of territories that spanned the globe from the Americas to Asia. It held together for about 400 hundred years and made its mother country a fortune, wealth that persists today. What was the reason that the Netherlands, a tiny country with very few natural resources, was able […]

Leaving Afghanistan and why America doesn’t win wars

Since World War II, the United States has lost just about every war that it has fought in a developing country. It has epitomised the tragedy of a world power’s incapability in asymmetric conflicts. The latest war, from which the US is now bowing out without having achieved its original objectives, is the 20-year conflict […]

The Suffragette: The History of the Women’s Militant Suffrage Movement

THE SUFFRAGETTE: THE HISTORY OF THE WOMEN’S MILITANT SUFFRAGE MOVEMENT By E. Sylvia Pankhurst (1882 – 1960) This history of the Women’s Suffrage agitation is written at a time when the question is in the very forefront of British politics. What the immediate future holds for those women who are most actively engaged in fighting for […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.