Reading time: 28 minutes

The blue waters of the Mediterranean became a vicious battleground far removed from the familiar landscapes of Australia during the Second World War. Yet Australian airmen and sailors played a pivotal role in this vital theatre. Their actions defending the beleaguered island fortress of Malta reverberated throughout the then British Empire and helped turn the tide of the war.

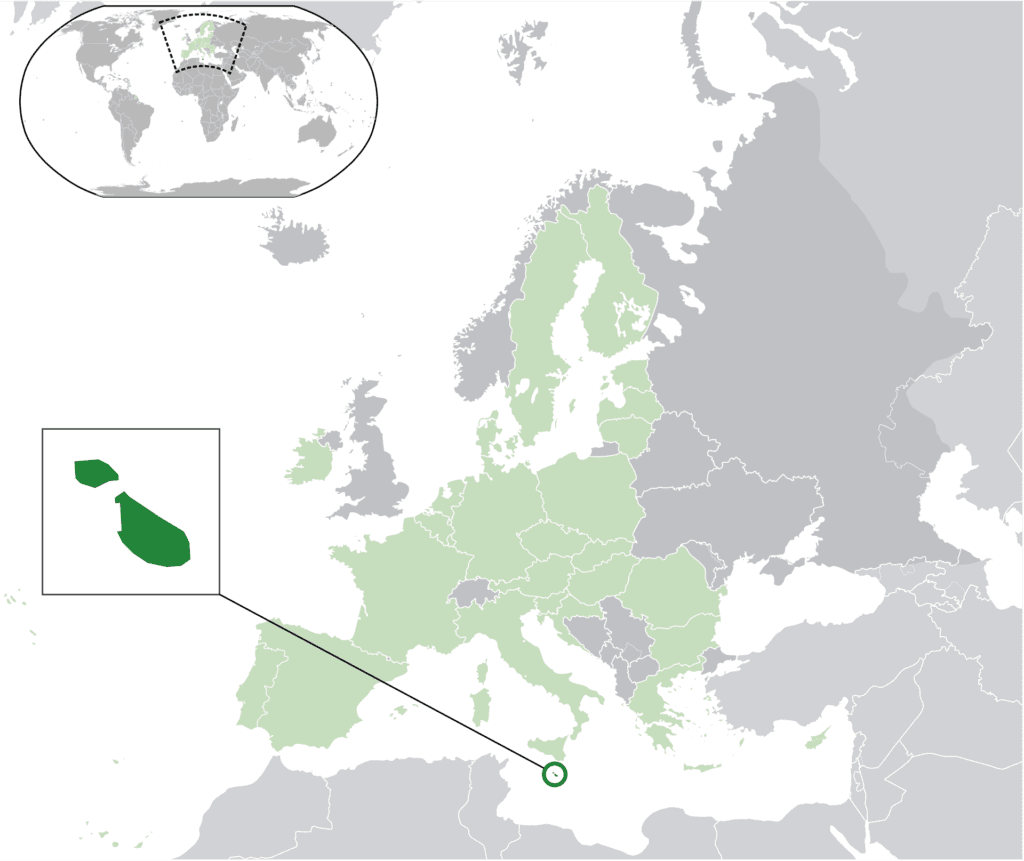

Malta was a small dot on the map, but one of the most strategic locations of the war. Its airfields and naval facilities harassed Axis shipping in the Mediterranean and made it difficult to supply their North African armies. The island was subjected to two years of relentless Italian and German bombing, becoming the most bombed place of the war, and a symbol of defiance as a result.

Australian bravery was an integral part of the defence of this all-important bastion in the middle of the sea. Australians battled for control of the skies over the island, patrolled the blue waters around it, and manned the defences on land. We will uncover the stories of those who served in the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) and Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) during the siege of Malta, as well as Australians serving in the British Royal Air Force and Royal Navy. Malta is well worth visiting, doing so will give you a deeper understanding of the experiences of the Australians who served there.

Malta at the crossroads of history

Malta’s significance extends far beyond the battles of the Second World War. Its history stretches back to neolithic times, and to fully understand the spirit that fuelled the island’s stubborn defiance, we must first delve into its rich past.

Malta has always been a strategic island at the confluence of competing powers. The first stone-age settlers came from the European mainland more than 8,000 years ago. Next came the Phoenicians, those great sailing people who established colonies across the Mediterranean in the late Bronze Age. They settled in Malta and built Medina, the island’s first city. Malta became Carthaginian after the fall of the Phoenicians, and was heavily fought over during the Punic Wars. Rome conquered Malta, but the Maltese never really adopted Roman culture. Roman coins were rarely used. Roman architecture was shunned. Evidence of Phoenician and ancient Greek writing from the Second Century CE have been found, showing the island’s spirit of resistance to colonisers goes back thousands of years.

Malta was later occupied by the Arabs, along with Sicily, in 870. The Arabs brought agriculture and new fruits to the island, and the Arabic language merged with the local languages to create a new unique language: Maltese.

Then came the Normans. These tall, blonde-haired descendants of the Vikings conquered the island in 1091, and it was merged into the Catholic church and governed by Sicily. The Arabs were expelled. The Knights of Saint John turned the island into a fortified garrison during the Crusades, forever cementing Malta to the image of crusading knights.

The island was besieged by the Ottoman Turks in 1565, known as the Great Siege of Malta. Ottoman cannons and siege towers spent three months attempting to breach the great walls of the fortress, but the brave Maltese knights under the Frenchman Jean Parisot de Valette fought them off.

Napoleon was the next invader. His French armies were unpopular on the island, especially after they pillaged the homes and churches of the locals. The Maltese rebelled, helped by the English. The Royal Navy blockaded the French on the island, and the garrison surrendered. Malta became British in 1814.

The strategic importance of Malta

Malta’s location in the heart of the Mediterranean has made it a critical crossroads between competing civilisations. Control of Malta has meant control of the sea for centuries. This strategic significance intensified during World War Two, as whoever held Malta could disrupt shipping to and from the African continent. Britain was able to choke Axis supply routes as a result.

Benito Mussolini had declared war on France and Britain in 1940 and the Italians had launched an attack on Egypt from Libya, an Italian colony. The British and Australians repulsed the attack and almost overran all of Italian North Africa until the German Afrika Korps arrived to save the day. Under the daring German general, Erwin Rommel, who would earn the moniker “the Desert Fox,” the Afrika Korps routed the British and pushed them all the way back into Egypt, surrounding the vital port of Tobruk in the process.

The Afrika Korps had only 33,000 men and one light Panzer regiment with 33 Panzer III Ausf. G tanks with the short-barrelled 50 mm gun, and 12 upgunned 75 mm Panzer IV Ausf. E tanks. These were enough to threaten the British Eighth Army, which was made up primarily of infantry and light armour in 1941. Only the heavy British Matilda tanks could handle the Panzers, but there weren’t many in theatre.

Germany began to reinforce its African army with the 15th Panzer Division in mid-1941, while the Italians rebuilt their shattered 10th Army. The decent Italian M13/40 tank also arrived in large numbers. Rommel’s goal was drive onto the Suez Canal and cut the Allied supply lines from Asia and India.

Tanks, ammunition, food, and fuel was sent by rail from the Reich to the south of Italy, where it was loaded onto ships. Naples was the largest and most active Italian port with direct sea routes to Tripoli, and the Naples-Tripoli route was only 550 miles, which a convoy could complete in a day and a half. The Taranto-Benghazi route was nearly the same distance, although Benghazi lacked the same heavy lift capabilities of Tripoli so unloading took days. The port was also in range of British bombers and came under repeated night attack. The bulk of Axis supplies was transported to North Africa with Italian ships to Tripoli.

These sea routes were protected by distance. They were 800 miles from Gibraltar and nearly 400 miles from Alexandria. The Regia Aeronautica, Italy’s air force, had 2,000 operational warplanes able to cover the sea routes to North Africa, making it extremely dangerous for the Royal Navy to attempt interception. German Luftwaffe aircraft also began to arrive in strength in the theatre with the fall of Greece and Crete.

Only Malta stood in the way. This tiny island lay astride the main Naples-Tripoli supply route and small planes taking off from Malta’s airfield could easily reach both of Italy’s main sea routes. This fact was not lost on either side.

Malta’s trial by fire

Malta was a peaceful paradise prior to the outbreak of the war. This small island measures a mere 17 miles by 9 miles. Its rocky coastline gave way to gently rolling hills and several fertile valleys were olives, grapes, apples, and other fruit were grown. The island has never been heavily populated, although there were many charming villages dotted across the land. Most its 280,000 inhabitants were concentrated in Valletta, the capital of Malta and the historic heart of the island. The imposing fortress that had withstood sieges past was here, as was the main harbour.

The silent city of Mdina, called Medina then, was much more serene than bustling Valletta. It featured winding medieval streets and a healthy tourism industry. There were three airfields on the island: Luqa, Hal Far, and Ta Qali. Only Luqa was built with concrete runways and could remain open after wet weather. The other two airfields became a swampy soup until the grass dried.

Malta’s defences had been severely neglected during the inter-war years. The fortifications were outdated, and there were only 12 old Gloster Gladiator biplane fighters on the island when war began, six of these still packed in crates. There were no modern anti-aircraft guns nor was there any artillery to hold an invader at bay.

Things changed for Malta after the outbreak of war. Neville Chamberlain was replaced by Winston Churchill as Prime-Minister and several batteries of anti-aircraft guns were shipped to the island.

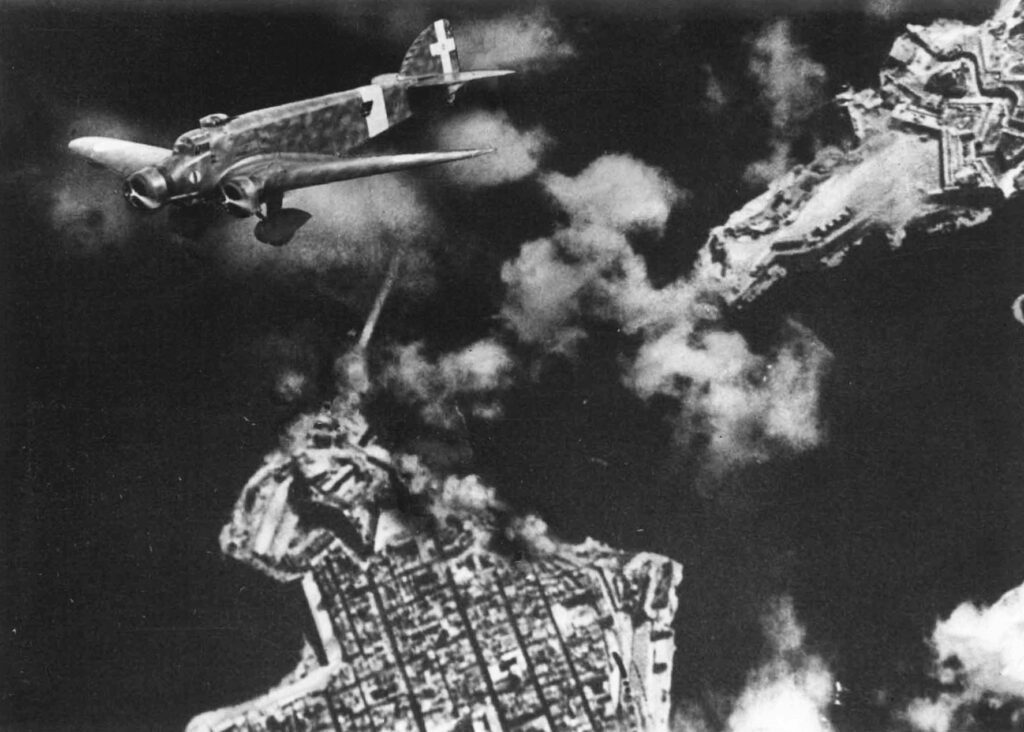

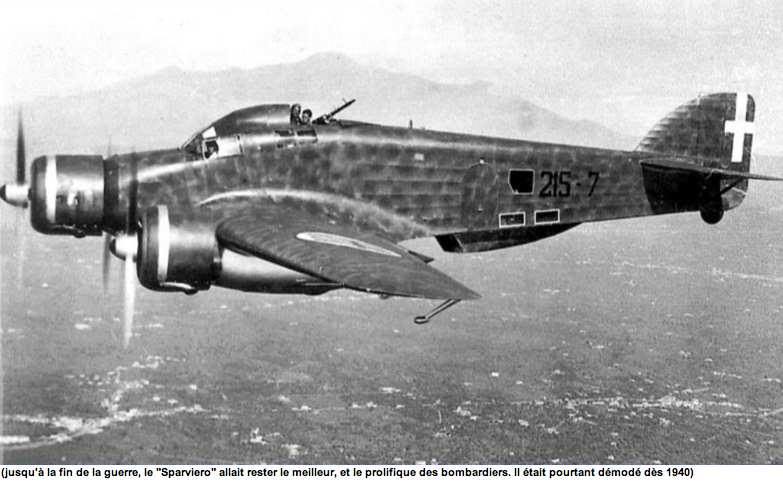

Italy declared war on France and Britain on June 10th, 1940. The first bombing raid of what would become more than 3300 during the war began a few hours later. The first wave came in the form of 55 Italian S.M.79 three-engined bombers, escorted by 21 Macchi C.200 fighters. This force hit the three airfields, dropping more than 140 bombs but doing little damage. Another wave of ten bombers returned that evening and dropped bombs on the Grand Harbour in Valletta.

Three of the ancient Gladiator biplanes managed to get airborne and even shot down an Italian bomber. They became known as the Hal Far Fighter Flight. The men flying these old biplanes were originally flying-boat pilots with no experience flying fighter planes in combat.

The bombers came again the next day, and the day after. The siege of Malta had begun.

Seven pilots defended the skies of Malta for 18 days straight. They used the same three Gladiator fighters, with the ground crews swapping out pieces from grounded planes to keep them airborne. These planes became known as ‘Faith’, ‘Hope’, and ‘Charity’ to the Maltese and in the world’s imagination.

Reinforcements arrived in the form of four Hawker Hurricane fighters, which landed on Malta at the end of June. More Hurricanes trickled in over the next few months as they could be spared. These combined with the Gladiators to form 261 Squadron RAF under Air Commodore F.H. Maynard, who took command of all air operations for the island. Several Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers and a Wellington Mk.I twin-engined bomber also joined the island to begin intercepting Italian shipping en route to Africa. The Swordfish were particularly effective, and launched a raid on the Italian port of Augusta, Sicily in late June and sank a destroyer, damaged a heavy cruiser, and destroyed the port’s oil facilities.

Despite these acts of bravery, Malta’s plight remained dire. The Axis relentlessly pummelled the island in a bid to wear down its resistance. Day after day, waves of Italian and German bombers unleashed destruction from the skies. Valletta, the vibrant capital, was reduced to rubble. The Grand Harbour, once a bustling port, was hammered into a wasteland of sunken ships and twisted infrastructure. Civilian life became a daily struggle for survival as people sought refuge in underground shelters and struggled to find food and water.

The island’s anti-aircraft defenses were pitifully understrength, and the few fighter aircraft suffered a relentless attrition rate. Yet, despite the devastation, a defiant spirit prevailed. Maltese civilians joined the war effort, repairing damaged airfields, operating anti-aircraft batteries, and tending to the wounded. The Royal Air Force, recognising the island’s plight, poured in reinforcements, but these brave pilots often flew straight into a maelstrom of Axis fighters.

Throughout 1941 and 1942, the Siege of Malta continued unabated. Axis bombing raids became a relentless, daily occurrence. Food and fuel were in desperately short supply. However, Malta refused to yield. In April 1942, King George VI awarded the entire island the George Cross, the highest civilian award for heroism, in recognition of their collective bravery.

The tide began to turn as supplies eventually reached the island and additional fighter squadrons arrived. Malta was transformed from a besieged bastion into an offensive launchpad. Allied forces based on the island now harried Axis shipping and supported operations in North Africa. Exhausted and battered, but with its strategic importance reaffirmed, Malta had endured its trial by fire.

Australians and the Siege of Malta – Video

The RAN in the Mediterranean

There were six Australian ships serving with the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet at the outbreak of the war with Italy. They were all based at Alexandria.

HMAS Sydney – Light cruiser

HMAS Vampire – V Class destroyer

HMAS Vendetta – V Class destroyer

HMAS Voyager – V Class destroyer

HMAS Waterhen – V Class destroyer

HMAS Stuart – V Class destroyer transferred from the Royal Navy

This flotilla was dubbed “the Scrap-Iron Flotilla” by Joseph Goebbels in German propaganda, because the ships were all built during the Great War and were outdated by 1940 standards. The men of the RAN wore that moniker with pride.

One of these, HMAS Vendetta, was in Valletta harbour during the first air raids. Supply Assistant Gordon Hill was one of the destroyer’s crew and he recounted his tale to the Naval Historical Society of Australia.

On 10th of June I left the ship and was walking to the canteen to shower and spend the evening ashore when two army officers excitedly told me ‘the balloon has gone up’ That expression took a while to sink in but I soon realised that Italy had come into the war. The immediate fear was an Italian invasion by sea and air. Living in the NAAFI canteen was bad enough but we were now to be quartered in a tunnel alongside the ship in the graving dock. Fifty men took their hammocks and laid them on the damp tunnel floor and turned in. Next morning we were covered by bites from fleas that infested the walls of the tunnel. The only relief was to dive into the harbour. That tunnel was our home for four weeks while we worked on the ship.

Supply Assistant Gordon Hill

The Grand Harbour at Valletta became the primary target for the Regia Aeronautica, and it was bombed relentlessly. HMAS Vendetta operated from this harbour for two months, helping to capture an Italian cruise ship full of civilians, and escorting British ships in and out of the harbour. The destroyer finally left Malta in November, 1940, miraculously without being damaged by a single bomb during its ordeal.

HMAS Voyager spent time in Malta refitting in September 1940, after a hectic series of combat actions that saw her sink two Italian submarines, as well as take part in the Battle of Calabria.

The British raid on Taranto in November knocked out three Italian battleships and a heavy cruiser, forcing the Regia Nautica to withdraw its main fleet to the safety of Naples, where it would be safe from British aircraft. This one move shifted the strategic situation in the Mediterranean and gave the Royal Navy dominance of the sea. British U-class submarines began arriving in Malta and used the island as their base of operations for raids on Italian convoys. These submarines could only resupply at night, and they spent the daylight hours settled on the bottom of the harbour, out of view of Italian aircraft.

While the larger battleships and carriers of the Royal Navy focused on major confrontations, a battle equally vital played out across the Mediterranean’s vast expanse. RAN destroyers took their place alongside British counterparts in the ceaseless struggle to protect supply convoys – the lifelines that kept the North African campaign and Malta itself fueled and armed. Italian destroyers, torpedo boats, and relentless aerial attacks by both Italian and German aircraft made these missions perilous. RAN ships played a key part in Operation Substance, a critical effort to resupply Malta in July 1941, demonstrating their bravery and tenacity.

Operation Substance was a resupply convoy from Gibraltar to Malta. The convoy was codenamed GM1 and was made up of a troop carrier and 13 merchant ships. It protected by a massive British and Australian battle fleet, codenamed Force H, that included:

- the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal,

- the battleship HMS Nelson,

- The battlecruiser HMS Renown

- Four cruisers

- 18 destroyers, including HMAS Nestor

Axis reconnaissance spotted the convoy almost immediately. Italian warplanes began bombing the force on 23 July, 1941. HMS Ark Royal launched several Fulmar naval fighters but three of these were shot down by the escorting Italian fighters. The cruiser HMS Fearless was sunk and the destroyer HMS Firedrake was so badly damaged, she had to be towed back to Gibraltar. HMAS Nestor fought off several dive bombing attacks and an Italian torpedo boat attack, narrowly avoiding being struck. One of the transports was heavily damaged and Nestor pulled up alongside her, took on all her crew, and successfully towed the ship to Malta.

The waters of the Mediterranean bore witness to numerous clashes in which RAN vessels proved their mettle. On 21st June, 1940, just days after Italy entered the war, the HMAS Sydney joined with the British cruisers HMS Orion and HMS Neptune and shelled the Italian port of Bardia in Libya, marking Australia’s first shots of the war against Italy.

HMAS Sydney was engaged in an epic battle with the Italian fleet just a week later, when she was part of a convoy sailing from Alexandria to Malta. Three Italian destroyers attacked the convoy, and although they were driven off, one of them, Espero, traded shots with the Australian cruiser. Four of Sydney’s 6-inch shells (152 mm) hit the Italian destroyer and the ship exploded in a fireball.

Sydney was engaged again a few weeks later. She was part of a British fleet of four cruisers, three battleships, a carrier, and 16 destroyers tasked with escorting another Malta-bound convoy. The force came under air attack. A British submarine located a large Italian fleet, including two battleships, and British Admiral Andrew Cunningham, commander of naval operations in the Mediterranean, surmised the Italians were escorting a convoy of their own. The British fleet moved to intercept this Italian force and let the merchantmen continue on their own.

Sydney was the first to spot the enemy fleet at 14:45 on 9 July. It was a force of five Italian cruisers. HMAS Sydney opened fire at 15:00 at a range of 21 km. The Italians returned fire and shells exploded all around the ships of both fleets. Sydney managed to sink an Italian destroyer that was laying smoke, but not other ships were hit in the engagement.

The Australian cruiser was making a name for itself, and had earned several battle honours in the first months of the war. Her next big engagement came on 19th July when her and the British destroyer HMS Havock were assigned to intercept Axis convoys and ran into two Italian cruisers escorting four destroyers. HMAS Sydney snuck into a position behind the Italian force while maintaining radio silence, and at 08:30 opened fire on the Italians. In what became known as the Battle of Cape Spada She knocked the light cruiser Banda Nere out of action and then shifted her fire onto the cruiser Bartolomeo Colleoni. The Italian cruiser was smashed by Sydney’s deadly accurate fire and a salvo of torpedoes finished her off. Sydney picked up the survivors of the two Italian ships and took them back to Alexandria as POWs. This early victory boosted morale and showed that the Royal Australian Navy was a force to be reckoned with.

However, war at sea is rarely without loss. On January 10th, 1941, HMAS Vampire was among those escorting a convoy bound for Malta. During relentless German air attacks, the destroyer was struck, leaving survivors adrift and marking the first significant RAN loss in the Mediterranean.

The pivotal Battle of Cape Matapan further revealed the courage and skill of the RAN. In March 1941, HMAS Perth, along with other Australian and British ships, intercepted an Italian force including battleships and heavy cruisers. This daring night action led to the sinking of three Italian heavy cruisers and two destroyers, marking a major victory for the Allies despite damage to HMAS Perth.

The RAAF over Malta

With the relentless bombing of Malta well underway in early 1941, the Luftwaffe’s X Fliegerkorps, relocated to Sicily in December 1940, intensified its aerial onslaught. The island, a crucial Allied stronghold, desperately needed fighter defense. In response, the spring of 1941 saw the arrival of Hurricane fighters, flown by a truly international force. Pilots from the Royal Air Force (RAF), Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF), Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), South African Air Force (SAAF) and most importantly for this story, the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), formed a cohesive fighting unit. Three squadrons – 126, 185, and 249 – were formed and the muddy grass airfields of the island were reinforced. Anti-aircraft batteries began to arrive, especially the Bofors 40mm gun, which was particularly deadly against dive bombers.

Further bolstering Malta’s defenses were 12 Blenheim light bombers, tasked with disrupting Axis shipping lanes. These versatile aircraft harassed enemy supply lines, adding another layer to the island’s resistance.

Among the RAAF pilots who answered the call for Malta’s defense was Flight Sergeant Tony Boyd. A young Queenslander, just 21 years old, Boyd had traded his jackaroo life for the RAAF in 1938. He was sent to Canada for training in 1939 and then England in 1940. There he flew Hurricanes with 242 Squadron, the legendary unit of Canadian fighter pilots led by British ace Douglas Bader, during 1940 and 1941. These experiences served him well as he arrived on the beleaguered island in early 1942.

By May 1942, the Luftwaffe operations over Malta had reached a devastating peak. The skies became a constant battleground, a swirling vortex of dogfights between nimble fighters. RAAF pilots, like Boyd, found themselves locked in desperate aerial duels with seasoned Luftwaffe adversaries.

Boyd gained international fame when he shot down six Bf-109 fighters, two Ju-88 bombers, and three Italian fighters in less than a month.

“We were jumped by three 109s at 14,000 feet shortly after scrambling,” Boyd wrote in his diary. “Five Hurricanes shot down, four pilots bailed out, one missing.”

During one flight, he spotted a formation of German bombers and dove on them. “Shot all my ammo into a Ju-88. Starboard engine caught fire. Claim one 88 probable,” he wrote.

He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) and the Distinguished Flying Medal (DFM), but was himself shot down and killed in December 1942 at the age of 22.

Interactive Map of Malta during WW2

The ragtag group of Commonwealth fighter pilots were facing extreme odds. The Hurricane Mk.II had been withdrawn from the skies over Europe because it was hopelessly outclassed by the German Bf-109F and the FW-190 fighters in production. These fighters were now over Malta in strength. The Blenheims, Swordfish, and Wellington bombers had to be grounded as they had suffered irreplaceable losses at the hands of these superior German machines.

The Luftwaffe and Commonwealth squadrons battled daily over Malta. It was a miniature version of the Battle of Britain. Valletta was smashed to rubble and the airfields were constant targets. The Grand Harbour was filled with sunken ships and twisted metal.

However, a glimmer of hope emerged with the arrival of Spitfires. This more advanced fighter promised an edge over the Luftwaffe’s Messerschmitts. Yet, these technologically advanced machines came with challenges. The Spitfires faced limitations on the resource-strapped island. Modifications were needed to shorten their takeoff and landing runs, crucial for Malta’s limited airstrips. Additionally, ground crews, accustomed to maintaining Hurricanes, struggled to adapt to the intricacies of the new aircraft. Several of these Spitfires were B-winged variants which included two 20 mm cannons. But there were no cannon shells available on the island and these planes were grounded. As a result, despite their arrival, Spitfires remained in limited use during the most critical period of the siege.

One Spitfire pilot was RAAF Flight Lt. J.W. “Slim” Yarra. He had been in England for a few months when he learned there was a posting somewhere secret. He quickly volunteered and was accepted.

“I had seen enough of England to suit me,” he later wrote.

His posting was Malta. He and several Australian and New Zealand pilots and ground crew sailed on the carrier HMS Eagle. They took off from the deck of the carrier 1,000 miles from the island and made the flight in three hours.

Slim Yarra destroyed a Ju-88 bomber a week after arriving, and then engaged in a grueling dogfight with a Bf-109 on May 12th, which he shot down. He was shot down himself two days later and crash landed, but was back in the air the next day, where he shot down two Italian Macchi MC.202 fighters. A week later he shot down two Bf-109s and another Ju-88. He was awarded the DFM in June, 1942, and continued to shoot down German planes until he was transferred back to England in July. During his three months on Malta, Yarra shot down 19 German and Italian aircraft, making him one of Australia’s highest-scoring fighter aces. He was killed over the English Channel on 10 December, 1942.

The RAAF pilots on Malta faced enormous challenges head-on. They displayed unwavering courage and tenacity, enduring constant combat, long hours, and the ever-present threat of death. Their resilience, alongside the international force of pilots defending Malta, became a major factor in the island’s survival.

Planning a visit to this battlefield?

Fill in the form below and a History Guild volunteer can provide you with advice and assistance to plan your trip.

Life on Malta

Australian servicemen stationed to Malta found themselves immersed in a surreal wartime experience. Their days were a stark contrast between fierce aerial engagements or running a gauntlet of bombs and torpedoes at sea, to moments of Mediterranean pleasure surrounded by the historic beauty of Malta. They formed a unique and enduring bond with the people of the island, shaped by their shared experience.

Most of the Aussies on the island were based around the airfields. They slept in tents set up in gullies and among the rugged hills close to the airfields but sheltered from Axis bombers. The operational heart of Luqa, Hal Far, and Ta Qali bustled with mechanics tending to damaged aircraft and ground crews preparing fighters for their next scramble.

When granted precious leave, Aussies ventured beyond the airfields, eager to explore the island’s historic heart. They visited the labyrinthine streets of Valletta and often helped to clear rubble, working shirtless alongside the locals to lift bricks and stones. British Tommies and sailors made up the bulk of the foreign forces on the island, so the Aussies spent a lot of time drinking and playing football and rugby with their English counterparts.

Strait Street was the main drag of Valletta, and although it was heavily bombed, the bars and restaurants never closed. There, Aussies on leave found escape. There were mostly men here, and there were daily fist fights and brawls between sailors and soldiers from different countries. British MPs had their hands full on Strait Street.

Interactions with the resilient Maltese people left a deep impression on the Australian servicemen. They witnessed civilians emerging from underground shelters after devastating air raids, their stoicism and determination mirroring their own. Aussies participated in church festivals, marveling at the Maltese traditions, and were invited into Maltese homes, sharing meals and stories of distant homelands. These encounters, born amidst war, fostered a deep respect and a shared sense of community.

Malta’s wartime reality meant a constant juxtaposition of duty and the pursuit of leisure amidst danger. The azure waters of the Mediterranean offered a tempting, yet risky, escape from the heat and dust. A quick swim between air raids was a gamble many took. Local sporting matches also provided a welcome distraction, with cricket games and boxing matches offering a semblance of normalcy.

Aussie ingenuity also found its outlet on the battered island. Mechanics salvaged parts from wrecked aircraft, transforming them into quirky souvenirs and mementos. A few even managed to assemble makeshift motorcycles and spent their leisure hours roaring across the pockmarked landscape.

Nights were a different matter. The drone of enemy aircraft and the wail of air raid sirens could be heard before the sun had fully set on most evenings. The only refuge for civilians and servicemen alike were the ancient tunnels and caves of the island. Aussies mingled with Maltese, Brits, Canadians, Kiwis, Indians, French, and Nepalese in these dank caves throughout the night as bombs exploded outside. AA guns fired constantly.

Australia’s heroes of the siege of Malta

Australia’s servicemen forged a reputation for bravery and dedication during the two-year siege of the island. Several individuals stand out, such as Ordinary Seaman Ian Rhodes, a reservist with the RAN serving aboard the British destroyer HMS Kashmir.

Rhodes manned his Oerlikon anti-aircraft gun as the HMS Kashmir went down following a vicious German air attack. He refused to abandon his post as the water swirled around him, firing relentlessly at the attacking Luftwaffe planes. He shot down a diving Stuka just before his ship went under, and won a posthumous Conspicuous Gallantry Medal for his efforts.

Then there’s RAAF bomber pilot Travis Falkiner, who became a scourge on Axis shipping. After joining the RAAF in 1940, he embarked on an impressive operational tour with 38 Squadron RAF, flying Wellington bombers. Day after day, Falkiner braved enemy fire on countless anti-shipping missions, delivering punishing blows to Axis convoys. His determination and skill shone through in the harrowing attack on ships in Naxos harbor, where his actions significantly contributed to a successful and daring raid that damaged several Axis transports and unloading cranes.

Lieutenant Warwick Bracegirdle, from Newcastle NSW, served on HMAS Perth and helped evacuate troops from Greece and then Crete. He displayed extraordinary composure and bravery during the Greece evacuation while towing a burning ammunition lighter away from other ships, risking his own life to avert further disaster. His actions that day earned him the Distinguished Service Cross, recognizing both his devotion to duty and his exceptional personal courage.

These inspiring examples represent just a fraction of the countless heroic acts performed by Australian servicemen in the Mediterranean. For every individual mentioned, there were many more—pilots defying the odds in battle-worn fighters, sailors enduring the relentless perils of the sea, and countless others whose commitment and sacrifice left an indelible mark on the conflict.

The Siege is lifted

The tide of war began to shift definitively to the Allies favour by mid-1942. Months of relentless defense by Malta, coupled with growing Allied air and naval strength, slowly eroded Axis control over the vital waterway.

The tenacious defense of the island had taken its toll on the Luftwaffe and Regio Aeronautica. Determined pilots, flying a mix of Hurricanes, Blenheims, and the increasingly prevalent Spitfires, inflicted heavy losses on Axis shipping. Estimates suggest that by mid-1942, Allied aircraft based in Malta were responsible for sinking a quarter of all Axis shipping attempting to navigate the Mediterranean. As Allied air superiority grew, convoys carrying desperately needed supplies reached Malta more consistently, bolstering the island’s defenses.

Furthermore, the arrival of American forces in the theater marked a significant development. American ships and aircraft started bolstering Allied air and naval strength in the Mediterranean, further tipping the scales in favor of the Allies.

This growing Allied air superiority became most evident on the battered island of Malta itself. There were more than 200 modern Spitfire fighters on the island by the end of August, complete with parts and cannon shells. These planes were more than capable of dealing with the Germans.

However, the Axis forces were not yet ready to cede control. On October 11th, 1942, German Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, commander of Axis forces in the Mediterranean, launched a brutal offensive aimed at finally subduing Malta. The Luftwaffe, in a desperate gamble, unleashed a 17-day aerial bombardment campaign. Yet the defending fighter pilots put up such a fight that the island was practically invulnerable by this point. The defenders, a seasoned mix of British, Australian, New Zealand, and Canadian pilots, exacted a heavy toll. German losses exceeded 100 aircraft compared to the Allies’ 12.

This decisive defeat shattered Axis air supremacy over Malta. Kesselring, facing a critical situation on the North African front with the British offensive at El Alamein and the American landings in Operation Torch, was forced to abandon his assault and redirect resources. October 31st, 1942, marked the last major air raid on Malta. The island, battered but unconquered, had emerged victorious from the siege.

Australia’s legacy on Malta endures

The battle for Malta was one of the most destructive in the Mediterranean. The Allies lost a battleship, two aircraft carriers, five cruisers, and 18 destroyers, as well as more than 400 aircraft lost. The island was the most heavily-bombed place on earth. More than 30,000 buildings were destroyed or damaged by bombs, including 111 churches and 50 hospitals. Valletta’s historic opera house and clock tower were utterly demolished. 2,300 servicemen were killed along with 1,300 civilians.

But the Axis also suffered heavily. 700 Axis aircraft were lost, along with 773 ships and 75% of all Axis supplies heading to Africa from Italy. Airplanes from Malta also sank 50 German U-Boats and 18 Italian submarines. All told, 17,240 Axis airmen and sailors were killed during the siege.

Australians were a key component of the defence of Malta and the ultimate Allied victory in the Mediterranean. Australians sailed alongside their British cousins, protecting the vital Malta convoys and sinking scores of Italian warships. They braved relentless German and Italian assaults in the skies above the island, and earned a reputation for being deadly fighter pilots. And on the island itself, Australians proved warm and friendly to the local civilians, suffering alongside them and earning their affection and respect.

There are three military cemeteries containing Australians on the island today. Capuccini, Pieta, and Imtarfa cemeteries are maintained by both the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and the Maltese government.

Podcasts about the Siege of Malta

Did my Relative Serve in these Battles?

Hundreds of thousands of Australians served in the Mediterranean during the Second World War. Some families know what their relative experienced during this often very important part of their life, but many do not. History Guild has a project where our volunteers research the service history of Australians who served in the Mediterranean. We have had a lot of interest in this service and have a large backlog of research to get through, so it currently closed to new entries.

We hope to re-open this service once we have finished our research on the current set of Australian servicemen and servicewomen.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.