Estimated reading time: 11 minutes

The Greenwood neighbourhood of Tulsa, Oklahoma was a hub for black business and wealth from 1906 to 1921.

By Caitlan Hester

Black slavery and the civil war were recent U.S. history. Segregation was in full force and the KKK was re-emerging. But Black Wall Street was booming.

One accusation would lead to an angry white mob storming Greenwood and massacring hundreds of innocent black men, women, and children.

Their story was nearly lost to U.S. history until the state of Oklahoma decided to shed light on what took place in May and June of 1921.

The Birth of Tulsa, Oklahoma

Tulsa was settled by the Native Muscogee (Creek) after the Indian Removal Act forced them from their home in the state of Alabama.

Tulsa had become a trading post, cattle town, and a stop on the railroad when legislators enacted the Dawes Act. The government took the tribe’s land held in common and divided it into individual lots as private property.

The U.S. government distributed these lots among individual members of the Creek under the condition that they renounce their tribe and assimilate as U.S. citizens.

The U.S. then took the ‘surplus’ land to be sold.

The sudden availability of land coincided with the discovery of oil south of Tulsa, causing a population boom.

In only 28 years, from 1882 to 1910 the population of Tulsa had gone from 200 Creek people to 18,000 people from all over.

The Rise of Greenwood and Black Wall Street

Many African Americans were in and around Tulsa before the oil boom because they had integrated into tribal communities.

Some of them had been slaves owned by Native Americans. While others left the south and relocated to Oklahoma after the civil war, searching for shelter in Indian Territory.

When the Dawes Act took effect, African Americans who belonged to a tribe acquired land in Oklahoma.

The Father of Greenwood, O.W. Gurley

Born to freed slaves in Alabama, and raised in Arkansas; 25-year-old O.W. Gurley was a postal worker when he decided to escape the racial oppression of the south and head to Oklahoma during the land grab.

Gurley had built up his savings with a general store in a small town named Perry, Oklahoma. He sold everything and took his earnings to Tulsa, to live out his most ambitious dream.

In 1905 he bought 40 acres of land on the black side of the train tracks. The city had been segregated and separated by Jim Crow laws.

Gurley began to map development for a black neighbourhood he named Greenwood. He created residential and commercial areas. He built a grocery store and a boarding house. He loaned money to those looking to start a business.

Gurley had the vision to create something for black people by black people.

Hannibal Johnson, author of Black Wall Street: From Riot to Renaissance in Tulsa’s Historic Greenwood District

Black people fleeing racial violence and oppression in the south flooded into Greenwood.

Within only 15 years of its founding, Greenwood was home to 10,000 African Americans spread out over 35 square blocks.

Greenwood had it all: doctors, dentists, realtors, and lawyers. Luxury hotels, two newspapers, prestigious schools, restaurants, movie theatres, nightclubs, a post office, a public library, banks, hospitals, and public transportation services.

At its peak, Greenwood was home to 15 black millionaires.

Gurley’s wealth grew. He went on to open a hotel, a masonic lodge, various rental properties, and an employment agency.

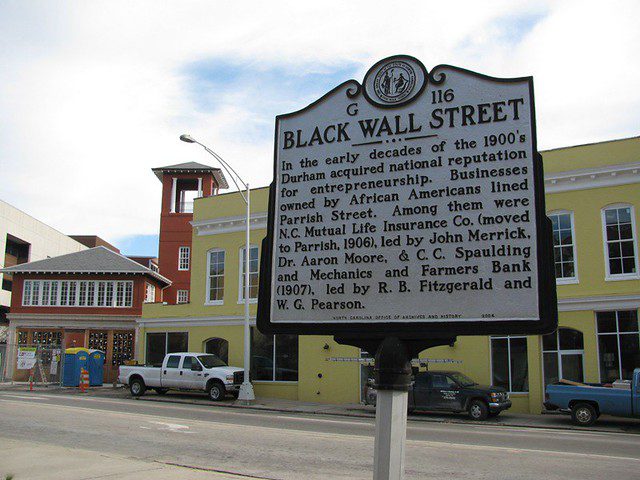

Booker T. Washington was the one who coined Greenwood as ‘Black Wall Street’.

It was the quintessential rags to riches story that defined the capitalist ‘American Dream’ of the 1900s.

The Racist Backdrop Surrounding Greenwood

Even though Greenwood was thriving, the United States remained a dangerous and oppressive place for the black population in 1921.

Slavery was an open wound. It had only been abolished for 41 years when Gurley founded Greenwood. And emancipation had been followed almost immediately by Jim Crow segregation laws.

After the First World War, the U.S. found itself in an economic recession. The recession increased competition for jobs and housing, causing scarcity and tension between poor white and poor black communities.

When white factory workers went on strike, black labourers were used as strikebreakers.

White soldiers returned home from WWI to find their jobs filled by black workers.

Hundreds of thousands of black soldiers returned home from the war to find they were still treated like second-rate citizens despite their equal sacrifice.

The Red Summer of 1919

Tensions rose and erupted in what is known as the Red Summer of 1919. Race riots broke out in 26 cities across the United States.

The race riots were, to a degree, instigated by President Wilson’s administration.

Wilson feared that the black population’s fight for justice and equality could lead to a revolution. He accused them of being inspired by the communist Bolshevik revolution in Russia.

Propaganda campaigns were launched to demonize communism, and black rights organizers were accused of communist plotting.

The U.S. government stood back as the Ku Klux Klan re-emerged, 97 lynchings were recorded, and 200 black sharecroppers at Elaine, Arkansas were massacred for trying to unionize.

Where Does Greenwood Fit In?

The affluent African Americans of Greenwood were attracting the wrong kind of attention. Their white neighbours who deemed them an ‘inferior race’ resented them for living a comfortable life.

Imagine the white racists of Tulsa watching their black neighbours with fine china, large homes, and nice clothes – thinking that they didn’t deserve it.

Dick Rowland and the Sexual Assault Accusation

Not everyone living in Greenwood was wealthy, and many Greenwood residents worked on the other side of the tracks in white Tulsa.

Dick Rowland was one of them. A 19-year-old black shoe shiner, he had been permitted to use a segregated bathroom in a building near his shoeshine station.

On Monday, May 30th, 1919 Dick Rowland took the elevator to the bathroom, as usual. And this is where the story gets muddled. Some accounts say that the white elevator operator, Sarah Page, screamed and Rowland fled the scene. Other accounts say that a nearby man heard a scream and reported it.

Either way, the police were called and Rowland was arrested.

Sarah Page knew Dick Rowland before this event. Her story about what happened in the elevator would change wildly over the years.

At the police station that day, the authorities concluded that whatever had happened was an accident or misunderstanding. They decided Rowland had tripped and fell onto Page or had stepped on her foot.

The police were set to release Rowland but opted to hold him for his safety because a mob was gathering outside the police station.

The Situation Escalates at the Precinct

It’s possible that what happened in the elevator wouldn’t have set off a chain reaction were it not for newspaper reporters who incited violence.

The Tulsa Tribune printed a front-page story claiming sexual assault and calling for a mob to gather and lynch Dick Rowland.

A mob quickly complied. They marched on the police station and demanded that the sheriff hand over Rowland. The sheriff refused and protected the young man from the mob by barricading the doors.

The News Reaches Greenwood

News of the mob quickly reached Greenwood. At first, 25 men responded. Committed to defending one of their community members from a lynching, they offered the sheriff their assistance in guarding the station.

The sheriff turned them away, insisting that it wasn’t necessary.

They left, but upon arriving back to Greenwood they heard more rumours of a larger mob of armed white men gathering and planning to storm the station.

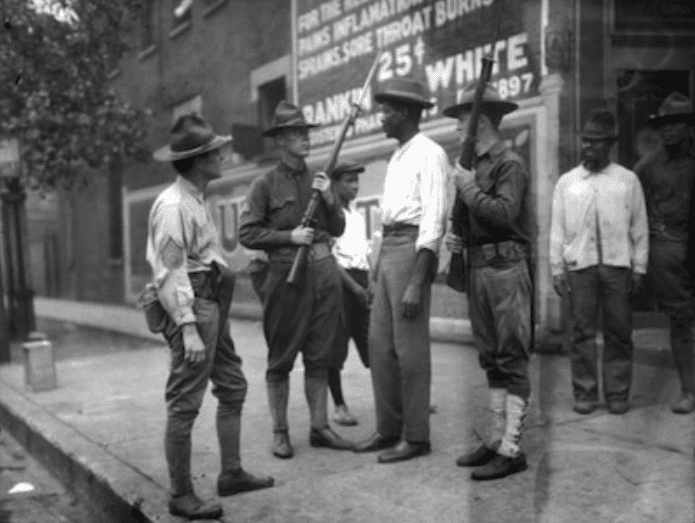

This time, 75 armed men and war veterans from Greenwood returned at around 10pm that night. But they were met by 1500 white men.

Things quickly got out of hand and in the chaos shots were fired.

The men from Greenwood, grossly outnumbered, fled back over the tracks. But they were followed by the armed mob.

The Tulsa Race Massacre

The angry white mob fell on Tulsa and attacked violently. Many of the police and National Guard who were sent in to keep order also took part in the violence and destruction.

The mob kicked in doors and looted the houses. After stealing everything valuable in the house, they set it on fire.

Innocent black men, women, and children of Greenwood were shot in the street and burned in their homes.

There were reports of machine guns being used, people being dragged behind cars, and local biplanes that flew over dropping homemade petrol bombs.

Firefighters that arrived to put out fires were threatened and run out by the mob.

This was not a heated attack that fizzled out over a few hours, but an organized attack that developed and lasted over 24 hours. They did not stop until all 35 blocks were burning.

The Red Cross estimated that the mob burned over 1,256 houses. That number excludes the private and public buildings and businesses that were also destroyed.

Over 60% of Greenwood’s population was left homeless.

Post-Massacre Silence and Cover-Up

The Oklahoma Bureau of Vital Statistics reported 36 deaths that year. However, historians and archaeologists set the number at 200-300 deaths.

The National Guard rounded up the homeless survivors of the Greenwood attack and placed them in internment camps, where survivors were kept as prisoners, unable to bury their dead.

Funerals were forbidden. Witnesses report bodies being thrown into the Arkansas river, loaded onto trucks, and put into mass, unmarked graves.

The city of Oklahoma was making a quick attempt to “clean up” before word could get out about what had taken place.

When Gurley and his family were released from the internment camp, they settled in Los Angeles, never rebuilding their wealth.

No one was ever tried or punished for the crimes that took place that day. And many placed blame on the black community.

The people of Greenwood worked to rebuild with no help from the city. They were not compensated by their insurance companies for the damage.

They received some aid from the NAACP and churches. But Greenwood would never fully recover.

The KKK gained more power in Tulsa and heightened the cover-up to keep what had happened out of national news.

The Tulsa Tribune got rid of the front-page story that had called the mob to action. They struck it from their bound volumes and records. State police also destroyed their archives of evidence.

With Tulsa under the eyes of the KKK, many people were afraid to speak out about the events that occurred that day.

Remembering Greenwood Today

Seventy-six years later in 1997, the Oklahoma state government decided to confront and shed light on this dark piece of Oklahoma history.

They gathered scientists and historians and established the Race Massacre Commission to better understand the facts around May 30 to June 1, 1919.

The historians commissioned began to conduct interviews with survivors and descendants of the survivors. Much of what we know today comes from their oral accounts.

The information that they’ve shared has led to the discovery of mass graves that archaeologists are currently working to excavate.

In 2004, the Oklahoma state department of education declared the topic as required reading for U.S. history classes.

Many other states, however, do not include the material in their curriculum. Therefore, multiple U.S. citizens are unaware of the Tulsa Massacre.

But recent occurrences of police brutality against the black community have motivated the public to re-examine the history of racism in the United States as a tool to understand why the people of the United States continue to struggle with systemic racism and violence today.

For More Information About Black Wall Street and the Tulsa Race Riots, Listen Here:

Articles You May Also Like

General History Quiz 127

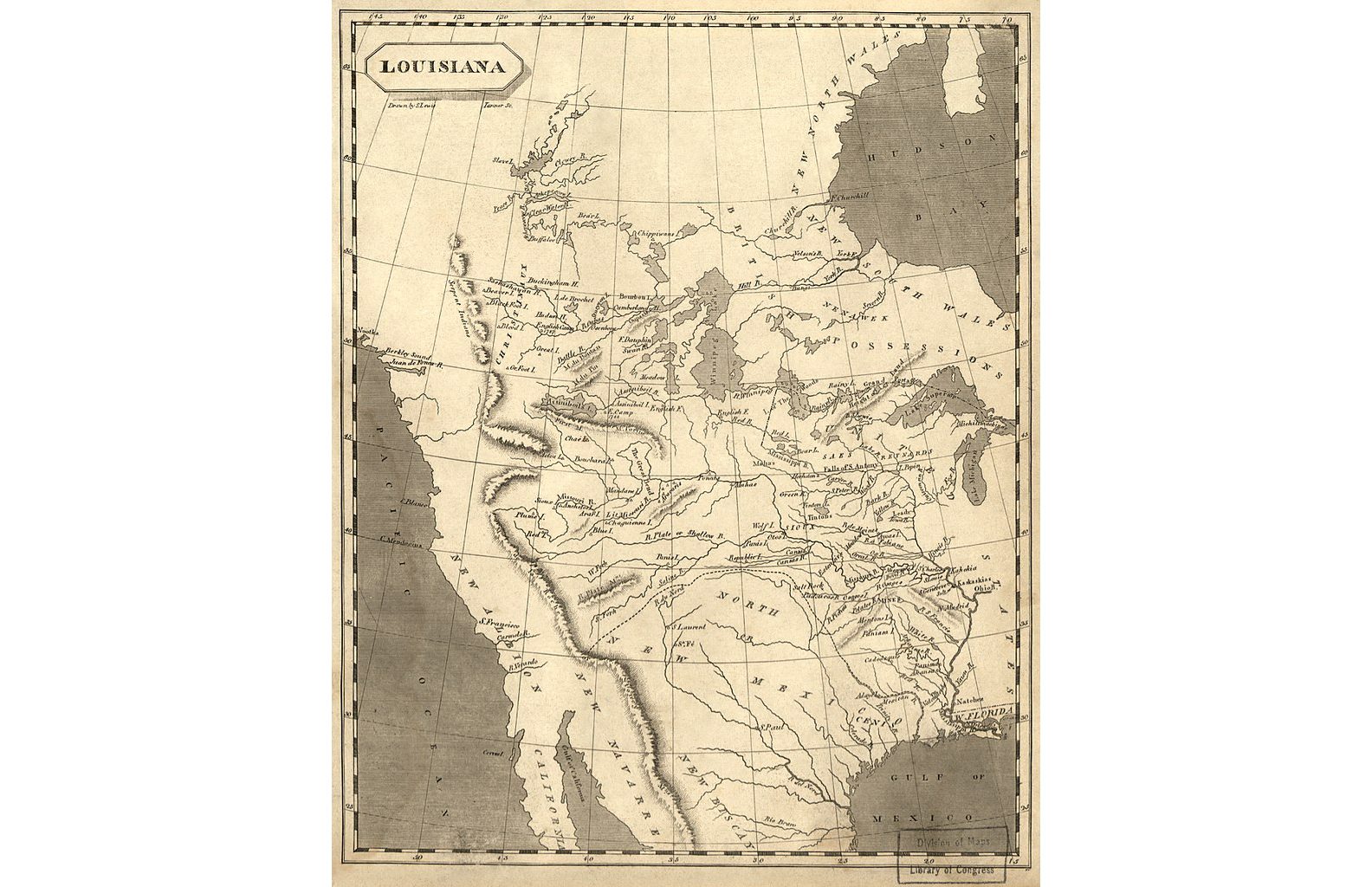

1. Which country did the USA purchase the Louisiana Territory from?

Try the full 10 question quiz.