Reading time: 11 minutes

The Civilisation Program, the Indian Removal Act and the Cherokee Trail of Tears, 1776 – 1860.

The diverse Native Americans of modern-day United States had lived in contact with European settlers since the early 1500’s.

By Caitlan Hester

When President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act in 1830, he enabled the forceful removal of Native Americans from all territory East of the Mississippi River.

For 300 years before the Indian Removal Act, numerous tribes had formed complex relationships with the European colonists. They fought over land and broken treaties, but also often coexisted.

It’s easy to think of the native people as Hollywood depicts them, warring tribes in the forests and grasslands far from U.S. cities.

But east of the Mississippi River, they were an integral part of 1800’s U.S. society.

There were Native American businessmen, teachers, clergymen, and representatives in Washington. They spoke English and French, intermarried with their white neighbours, and even owned slaves.

But no amount of cultural assimilation could have saved them from a growing nation’s greed for land and agricultural wealth. They were forcefully removed, causing the deaths of thousands and the downfall of once-thriving Native American nations.

From First Contact to the Fur Trade

The infamous Italian explorer Christopher Columbus reached the Caribbean Islands in 1492, spurring an immediate European rush to the Americas.

The Spanish flocked to the Americas to exploit natural resources and raw materials and convert the indigenous tribes to Catholicism.

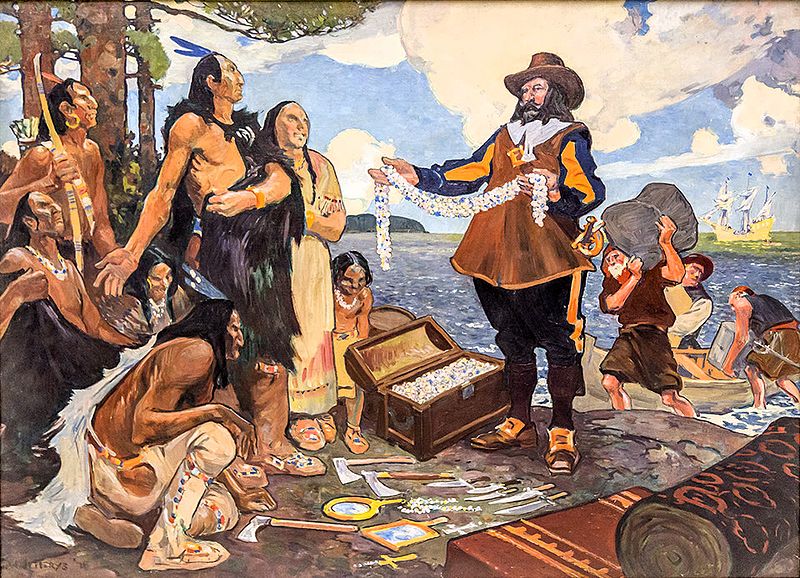

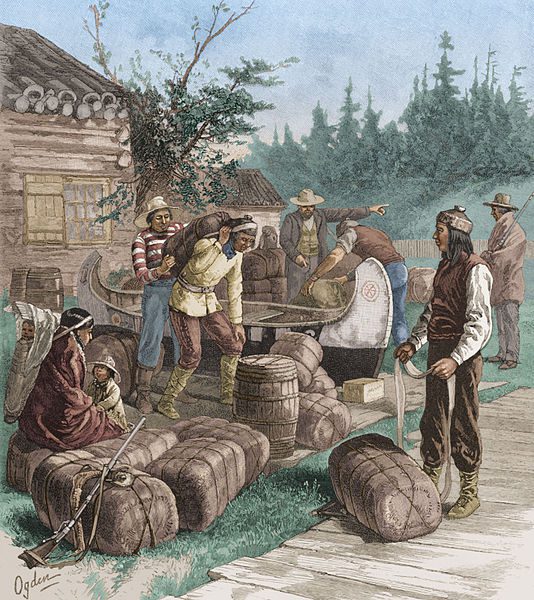

The French began seasonal fur trading with the native populations in North America, exchanging iron tools and weapons for beaver hides in the early 1500’s.

The popularity of beaver felt grew in European fashion, leading the French, British, and Dutch to establish permanent settlements in North America in the 16th and 17th centuries. European traders formed vital alliances with the tribes they traded with.

Native Americans and European Alliances

The London Company established the first permanent British colony in the U.S. as an economic venture in 1607. They were shortly followed by English Pilgrims escaping religious persecution.

British colonizers were in close contact with Native Americans almost immediately and found that they could communicate with them. Many tribes already spoke French at this point, as they had been trading with the French for almost a century.

As the British colonies grew, they became intertwined with native peoples in complex relationships that ranged from beneficial to disastrous – they traded goods, fought, forged treaties, intermarried, and unwittingly exchanged disease.

Complications intensified as Europeans began to dispute North American territories. Some tribes sided with the French while other tribes sided with the British during the French and Indian War.

During the U.S. Revolutionary War, some tribes maintained their alliance with the British, while those that were loyal to the French sided with the revolt and fought for the colonists’ independence from England.

After the Revolutionary War, the U.S. was a new country liberated from British rule. As such, they no longer intended to respect treaties the British had made with Native Americans. Tribes that had sided with the British were left to deal with the victors. At this point, some tribes fled to Canada, while others shifted alliance to the U.S. in hopes of keeping ownership of their ancestral lands.

President Thomas Jefferson and the Civilisation Program

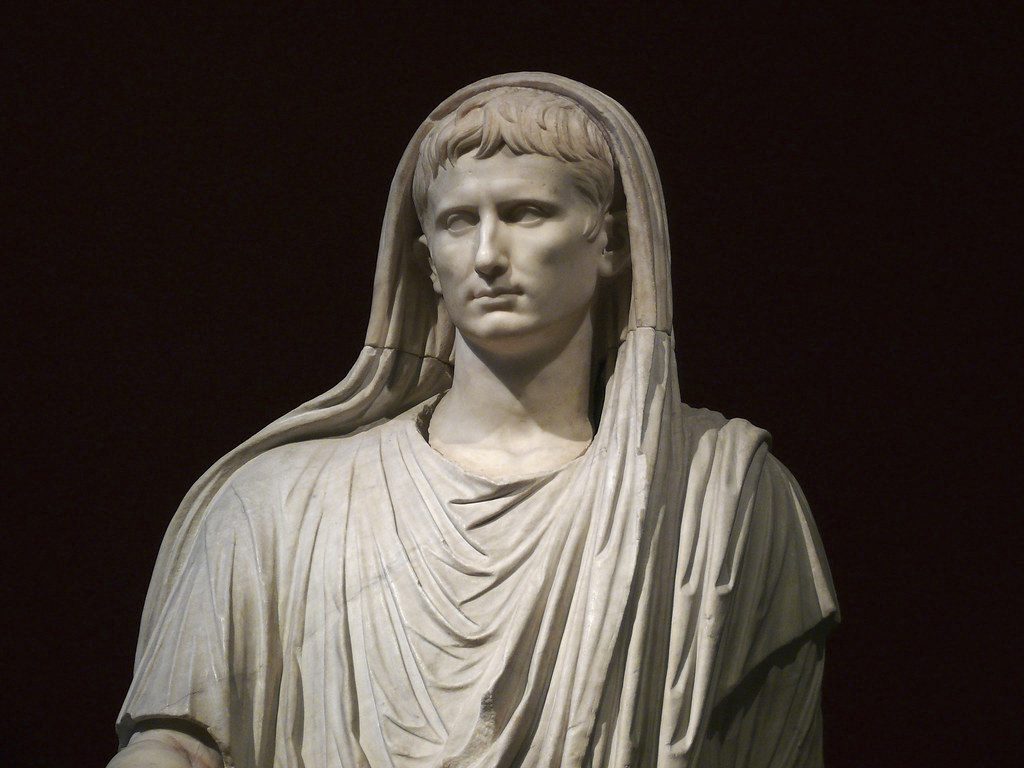

Following the Revolutionary War, the first U.S. presidential administration under President George Washington proposed a program to ‘civilise’ native peoples as a way to subdue them and prevent revolt.

But it was the third president, Thomas Jefferson, that imposed the Civilization Program.

What Changes Did the Civilisation Program Impose on Native Americans?

- Farming instead of hunting.

- Christianity.

- Land privatisation.

- Traditional Western divisions of labour between men and women – Men as farmers and women producing cloth through spinning and weaving.

‘The Five Civilised Tribes’

Many tribes, such as the Cherokee, had sided with the British during the Revolutionary War. This prompted them to adopt the Civilisation Program as a means to show their loyalty to the new U.S. government and avoid further conflict.

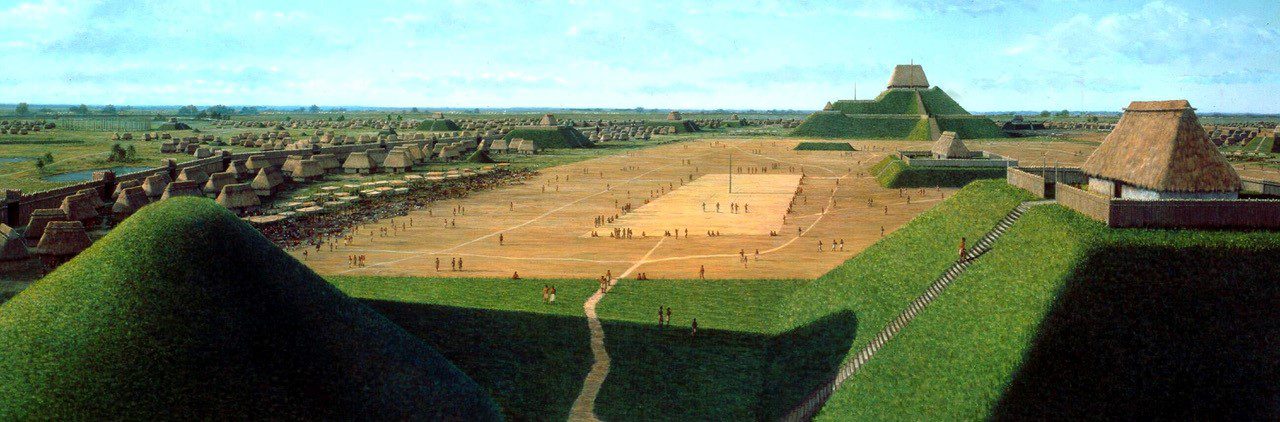

Some of the Native American nations that adopted the civilisation program were known by the U.S. as the ‘Five Civilised Tribes’. They were the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Seminole and Creek (Muscogee) – descendants of mound-building cultures.

These five tribes were considered ‘civilised’ in the early 19th century because they were literate in English, had centralized governments, adopted Christianity, used written constitutions, lived in Westernised homes, and practised farming.

Of course, today ‘civilised tribes’ is an ethnocentric label because it’s based on a western prejudiced view of what it means to be ‘civilised’.

Reasons for the Civilisation Program

Thomas Jefferson, similarly to George Washington, believed that British-sympathising Native American groups could be subdued by forming treaties and making them a part of white U.S. culture.

However, more important than cultural assimilation, Thomas Jefferson hoped to peacefully obtain the Native American’s vast hunting land that was protected under treaty.

Jefferson wanted to whittle the land away rather than take it outright. He feared that Native Americans if pushed, would band together and attack or create alliances with the English to the North and/or the Spanish to the South.

Investors, businessmen, and the U.S. government sought more land for large-scale plantation farming. They believed that if native peoples settled down and practised agriculture, they would have less need for the land, and would therefore sell it.

They also believed that if Native Americans took up husbandry, they would require farming equipment. They could obtain farming equipment from government stores on credit and rack up debt. Unable to settle their debts monetarily, they could give up their land in exchange.

Or so the government and businessmen believed.

However, this plot to obtain native land didn’t pan out as planned. The native peoples held the strong belief that land was held in common among them, not as private property. Tribes often farmed land as a community and shared their farming equipment.

Some years passed following Jefferson’s ‘civilisation program’ and even though many Native Americans were adopting the ‘white man’s’ culture, they were not parting with their land.

Coerced Migration

One thing that Thomas Jefferson did during his presidency from 1801 to 1809 was the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from Napoleon, a large tract of land west of the Mississippi River, which doubled the size of the U.S. at that time.

The U.S. government was able to talk many tribes into voluntarily relocating west of the Mississippi River by offering them treaties, guaranteeing permanent residence in larger tracts of land free from U.S. interference.

In 1812 approximately one-fourth of the Cherokee Nation voluntarily and peacefully moved to modern-day Arkansas.

Factions of many other tribes shortly followed – such as the Quapaw, the Lenape, the Miami, the Kickapoo, and the Choctaws.

But the Five Civilized Tribes in the Southeast did not sell their land and refused to relocate. They had cultivated farms and established wealthy nations. They had representatives in government, children in school, and many were educated professionals. Why would they move to an unknown place and start over?

The Indian Removal Act

The tension over land in the southeast continued to rise, exacerbated by black slavery and racism.

Cotton was a growing industry, helping the U.S. economy skyrocketed in the years following the war of 1812. The soil of Native American hunting land was perfect for planting because it had not been over-exploited.

Native American groups were also becoming unpopular because they provided a haven to runaway slaves. People feared that Native Americans could conspire with slaves and plan a revolt. The south thought that the freedom of Native Americans set a bad example, that Native American rights could motivate black rights.

To make matters worse, gold had been discovered on Cherokee territory in Georgia causing clashes between the Cherokee and outsiders.

Enter Andrew Jackson

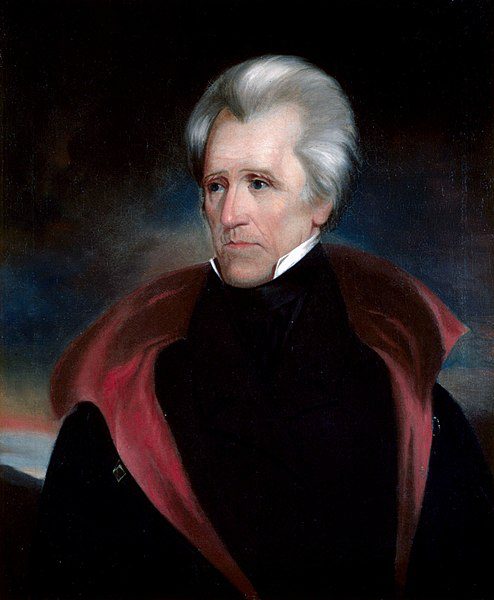

The 7th President of the U.S., Andrew Jackson, began to aggressively promote the Indian Removal Act. He touted the claim that it was an attempt to protect Native Americans and their culture. He insisted he had their best interests in mind.

The Indian Removal Act technically only allowed the U.S. government to negotiate the removal of Native Americans from the eastern U.S., but it would later become a forceful removal implemented by the U.S. military under President Van Buren.

The act was hotly contested and widely unpopular, receiving many petitions from the public pleading for its termination.

It barely passed through Congress and probably would not have passed if the south had not been over-represented in Congress. And if agricultural investors hadn’t backed it aggressively.

The Indian Removal Act was signed by President Andrew Jackson in May of 1830.

Following Through on the Indian Removal Act

In the years following the Indian Removal Act, many tribes accepted their ill fate and began their mandatory negotiations with the U.S. government. They signed treaties, organised their departure, and reluctantly but peacefully travelled on their own to their new, designated territories.

Others continued to resist. The Seminole tribe in Florida fought a series of battles for their land. It would take the U.S. almost 20 years, 30 million dollars, and the lives of 1500 soldiers to force the Seminole out.

The Treaty of New Echota

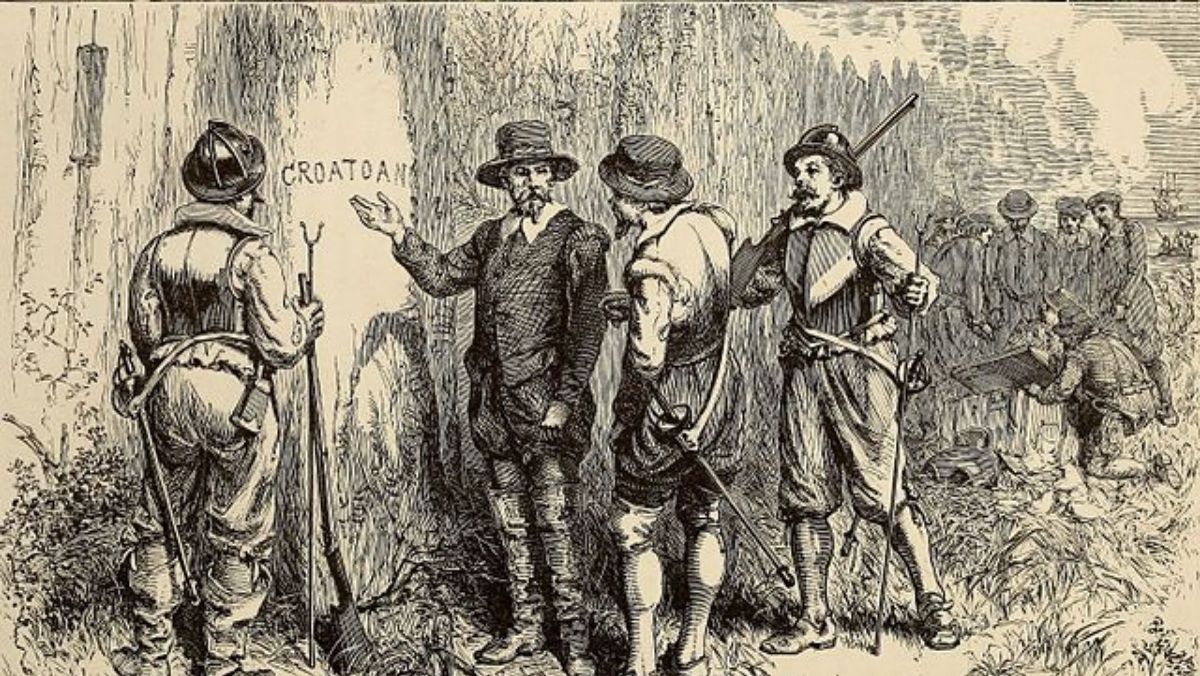

Five years after Jackson signed the act, the Cherokee Nation remained defiant and had not yet signed a land-exchange treaty with the U.S.

The U.S. government arranged to meet with a minority political faction of the Cherokee in New Echota, Georgia in December 1835.

This minority established terms in the name of the Cherokee even though they did not have the authority to do so. They signed the Treaty of New Echota which ceded the Cherokee Nation’s territory in the east.

They accepted territory in the state of present-day Oklahoma, and they took the monetary compensation offered by the government.

The Cherokee were given three years to relocate.

The Cherokee National Council considered this treaty void. After all, the council and the principal chief John Ross had not been present. John Ross travelled to Washington D.C. to protest and renegotiate, unsuccessfully.

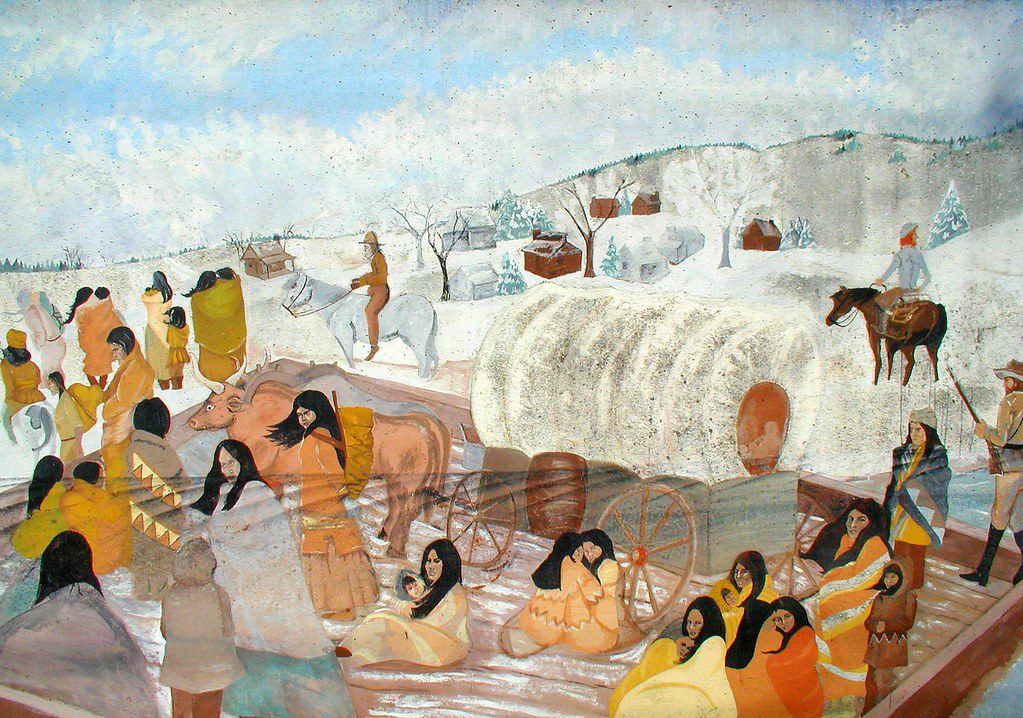

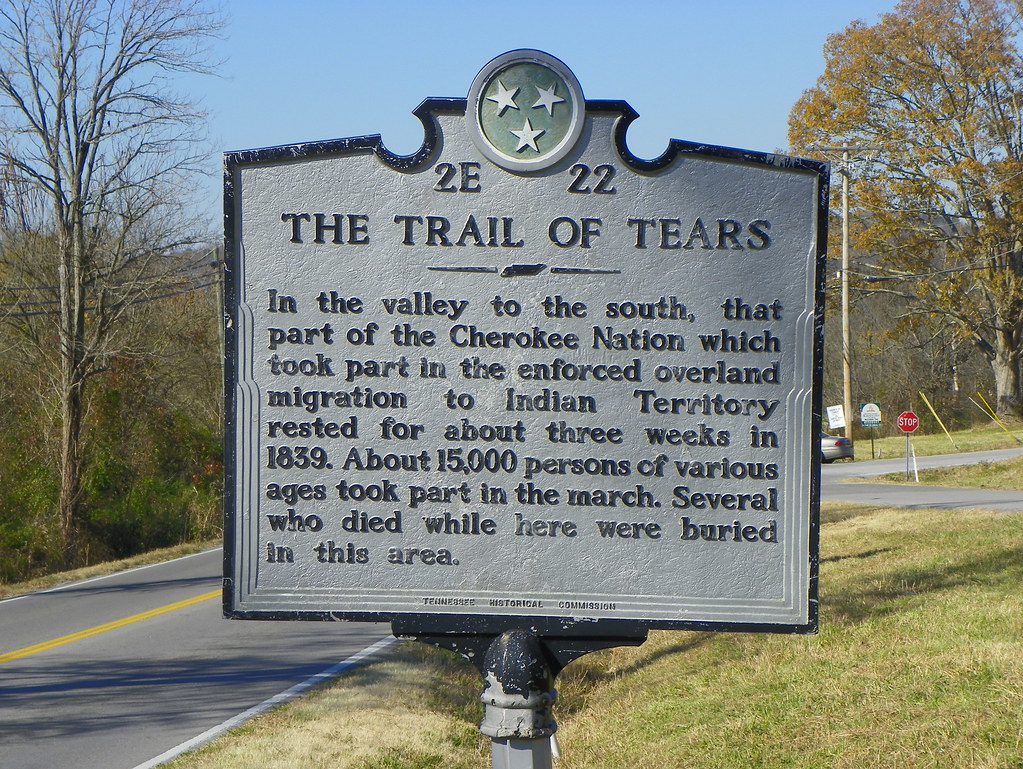

In those days, news travelled slow. Many Native American families were unaware of the Indian Removal Act and the Treaty of New Echota. Many were shocked and confused when troops arrived at their homes in 1838 to forcefully remove 16,000 Cherokee from their homes and march them west in what became known as the Cherokee Trail of Tears.

The Trail of Tears

Although the Cherokee Trail of Tears is the most well-known, over 100,000 Native Americans from diverse tribal affiliations were also forced to march westward under military supervision from 1830 to 1860.

Those who marched under military watch were those who hadn’t left voluntarily or those who were simply unaware that they had to leave.

Ripped from their homes as troops arrived, children and the elderly alike began the 800 to 1,200-mile march on foot, often with minimal supplies.

An estimated 25% died of exposure to the winter elements, measles, smallpox, dysentery, and starvation.

One Confederate soldier stated, “I fought through the Civil War and saw men shot to pieces and slaughtered by the thousands, but the Cherokee removal was the cruellest work I ever knew.”

Fallout and Broken Promises

The tragedy, unfortunately, did not end with forced removal from the eastern U.S.

When Native Americans arrived west of the Mississippi River, they were met with hostility from other Native American groups whose land they encroached upon.

The U.S. government broke its treaties, stripped the natives of their culture and languages, forced them off of their land, and marched them without resources in the dead of winter.

The U.S. government would later break its promises to leave Native Americans in peace west of the Mississippi River. The government would seize this land too, and continue to push Native Americans onto smaller reservations.

Articles you may also like

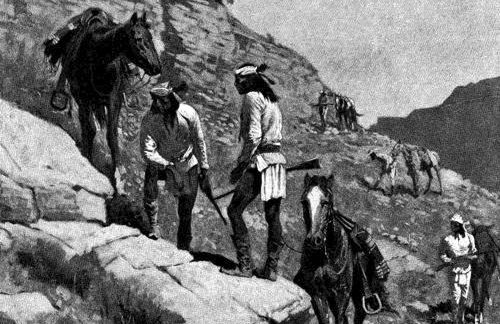

An Apache Campaign In The Sierra Madre – audiobook

AN APACHE CAMPAIGN IN THE SIERRA MADRE – AUDIOBOOK By John Gregory Bourke (1846 – 1896) An account of the expedition [of the U.S. Army] in pursuit of the hostile Chiricahua Apaches in the spring of 1883. (Book subtitle) Bourke was a Medal of Honor awardee in the American Civil War whose subsequent Army career included […]