Reading time: 5 minutes

After 140 years, researchers have rediscovered an Aboriginal ceremonial ground in Victoria’s East Gippsland. The site was host to the last young men’s initiation ceremony of the Gunaikurnai back in 1884, witnessed by the anthropologist A.W. Howitt.

Howitt’s field notes, combined with contemporary Gunaikurnai knowledge of their country, has led to the rediscovery. The site is located on public land, on the edge of the small fishing village of Seacombe. Its precise location had been lost following decades of colonial suppression of Gunaikurnai ritual and religious practices.

By Jason M. Gibson and Russell Mullett, Deakin University.

Researchers from the Howitt and Fison Archive project and the Gunaikurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation began searching for the site in 2018. While it lacks archaeological traces, such as middens, rock art, stone arrangements or artefact scatters, the importance of such ceremonial grounds is under-recognised. They are a central feature of Australian Indigenous conceptions of landscape and have considerable historical and cultural importance.

The Jeraeil

In the first few weeks of 1884, the Gunaikurnai peoples of Gippsland were preparing for a historic gathering. After decades of discussion and negotiation with Howitt, who was also a local magistrate and power broker, they finally agreed to allow him to record their secretive young men’s initiation ceremony, known as the Jeraeil.

Last held in 1857, just a few years before Howitt arrived in Gippsland, the Jeraeil had ceased to be performed due to tighter governmental restrictions and stern dissuasion from Christian missionaries.

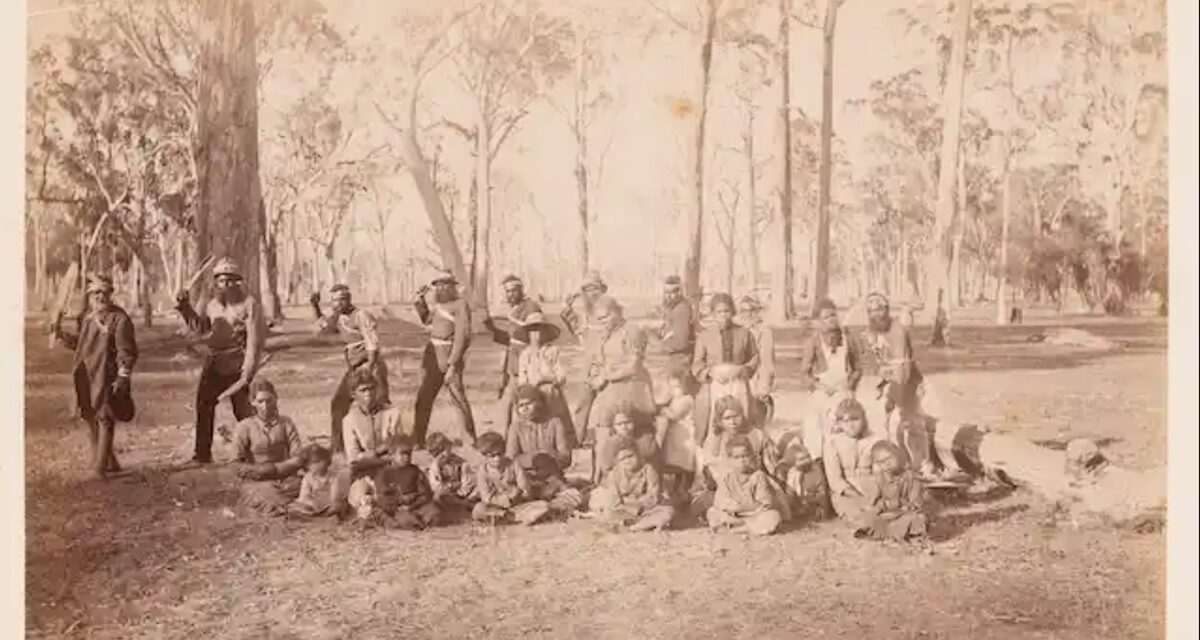

On January 30 1884, all the required Gunaikurnai people had assembled. Those coming from the Lake Tyers Mission came on the paddle steamer Tanjil. Those from Ramahyuck Mission, on the shores of Lake Wellington, arrived on the steamer Dargo.

Convinced that an Aboriginal initiation ceremony from this part of the colony would never be performed again, Howitt arranged and paid for his primary Kulin informants from the Melbourne area, William Barak and Dick Richards, to attend so they could contribute their commentary on Victorian ceremonies.

The event, which lasted four days, began with a series of preliminary ceremonies involving men and women singing together. The women kept time by beating on rugs folded in their laps and hitting digging sticks on the ground. Many of the performances that followed were restricted only to men, with six youths eventually initiated into manhood.

“It was remarkable,” Howitt commented, that although he had known many of these men “intimately,” and for a long time, they had kept these “special secrets […] carefully concealed” from him for many years.

Howitt’s published description of the Jeraeil, along with the equally significant work on similar ceremonies in New South Wales produced by Robert Hamilton Mathews, went on to influence the way religious life and ritual in south-eastern Australia was understood.

Finding the site

Lacking from Howitt’s record, however, was a precise description of where the historic ceremony had been held. A recent project to work on Howitt’s field notes in collaboration with Gunaikurnai people has uncovered new details, including a sketch map of the ceremony ground, sparking community interest in finding the site.

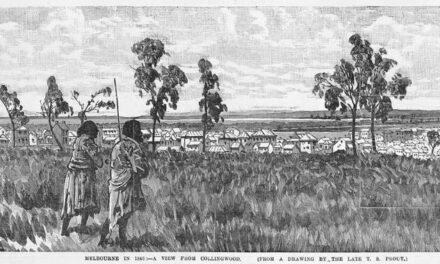

Howitt’s drawing of the ceremony ground, along with his notes and newspaper articles, enabled the research team to positively locate the site, on the edge of Seacombe, near the McLellan’s strait, which links Lake Wellington with the Southern Ocean.

The site’s significance lies not in any immediately observable physical property, but in its historical and cultural associations. They span the story associated with this place, including the local creation stories associated with Bullum Baukan (a woman with two spirits inside her); the complicated relationship with Howitt; interactions with other colonial authorities and the status of the Jeraeil in anthropological literature.

Discovery of this site means it is now protected under the (Victorian) Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006. All Aboriginal cultural heritage is protected in Victoria whether it has been formally registered or not and it is an offence to harm it.

The Jeraeil site is arguably one of the most significant of places in terms of the ritual and ceremonial life of Gunaikurnai people. However, the prospect of erecting signage at the Jeraeil site can produce mixed responses.

On the one hand, telling the world about these places might secure them. On the other, the Gunaikurnai live in a region dotted with monuments that remind people of the colonial violence enacted by men such as Scottish explorer Angus McMillian. One plaque brazenly describes McMillan as an explorer who achieved “territorial ascendancy over Gippsland Aborigines”.

Victorian Aboriginal cultural heritage continues to be damaged as happened with the recent partial destruction of the Kooyang Stone Arrangement in Lake Bolac. Some in the Gunaikurnai community fear too little is being done to protect such places but also worry about the public’s readiness to embrace Aboriginal cultural heritage.

Still, it is imperative places like the 1884 Jeraeil ground are better understood, recognised and protected. Not only does it tell a story of Aboriginal cultural practice but of shared Aboriginal and European interactions we should all know more about.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Articles you may also like

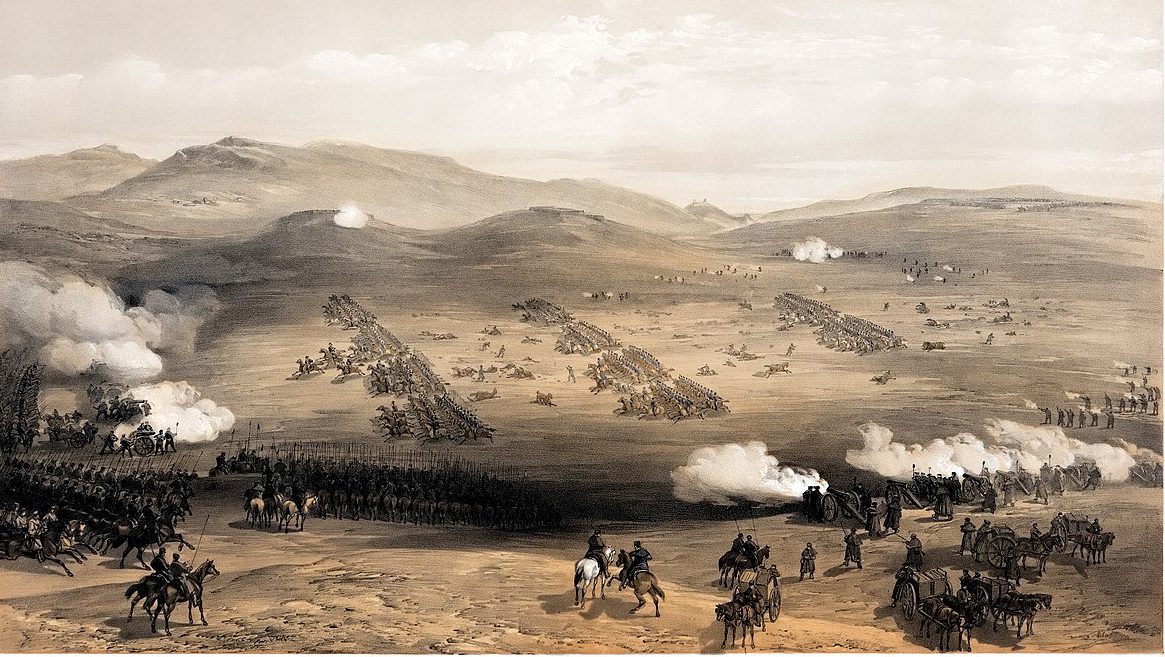

Could the Charge of the Light Brigade have worked?

COULD THE CHARGE OF THE LIGHT BRIGADE HAVE WORKED? Middle East tensions. Russian soldiers in Crimea. Western nations’ warships in the Black Sea. Those descriptions sound like Russia’s 2014 takeover of Crimea. But they also applied 150 years earlier during The Crimean War between Russia and a British-French-Turkish alliance. That war is largely forgotten now, apart […]

General History Quiz 70

Weekly 10 Question History Quiz.

See how your history knowledge stacks up!

1. Which leader said “We will bury you!”?

What was the Medieval warm period?

Reading time: 6 minutes

The Medieval warm period is an asynchronous regional warming caused by natural (not human-driven) climatic variation, whereas we are facing a homogeneous and global warming caused by human activity releasing too much greenhouse gas into the atmosphere.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.